The Cause of the Universe's "Odd Radio Circles" May Finally Be Known.

It's possible that objects caused by supernovae are so peculiar that they are referred to as "odd radio circles".

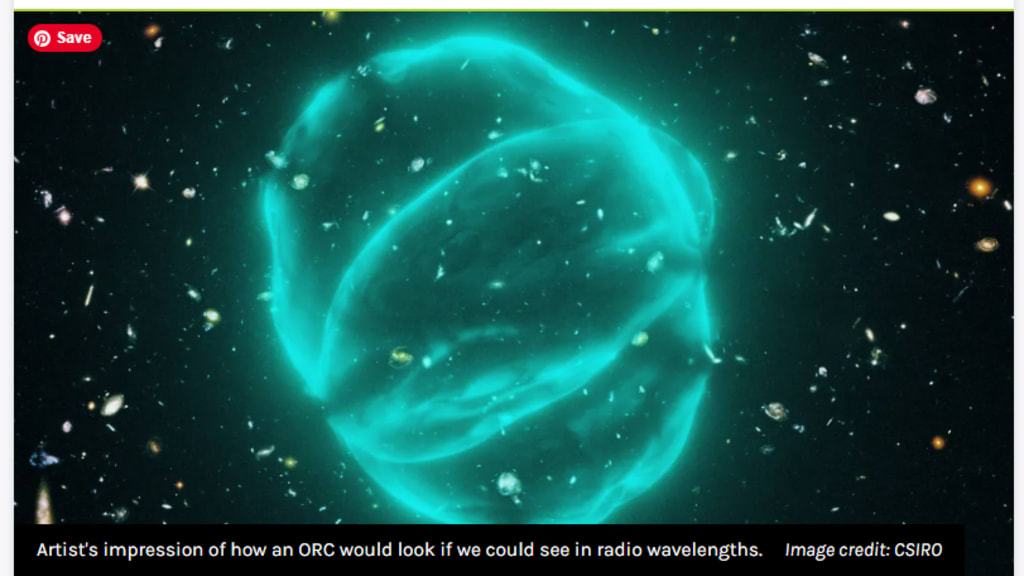

Large-scale gas fluxes from galaxies that are producing stars at an astounding rate are what give rise to the so-called Odd Radio Circles (ORCs). Astronomers have determined that massive winds are being produced by supernovae in those galaxies, resulting in the ORCs. Had it not been for the astounding magnitude of this phenomenon, which made the hypothesis seem improbable at first, it may have been the explanation all along.

Radio telescopes could only efficiently focus on limited portions of the sky at a time until recently. Anything too large was essentially invisible. Rather than taking pictures of the sky at random, as we have done with optical telescopes, there has been a trend to concentrate on areas where findings at other wavelengths lead us to anticipate finding anything.

This changed with the construction of the Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP) and the Murchison Wide Field Array, which capture such enormous areas that they enable extensive surveys. Utilizing the ASKAP, scientists found in 2020 that significant, roughly circular regions of the sky are radiating at comparable wavelengths. Upon verifying that they were not the consequence of malfunctioning equipment and failing to find a more plausible explanation, the discoverers dubbed them ORCs. The name is accurate, evocative of Middle Earth, and devoid of any potentially incorrect conjecture regarding the cause. Additionally, compared to the original attempt, WTF, it is less likely to offend.

Professor Ray Norris of Western Sydney University, one of the discoverers at the time, stated, "Supernova remnants are the only explanation for circles like these." Furthermore, these aren't supernova remains.

Because of their size, Norris and the other members of the team who discovered the ORCs believed they could not be supernova remnants. Near the centers of all ORCs that we have discovered are quite distant galaxies, and many of them are located too far from the galactic plane to be likely to be Milky Way components. But considering their angular size, if ORCs truly come from these galaxies, they are so massive that they even defy people who work in the field of mind-bending with scale. Even with their immense power, supernovae shouldn't be able to produce blast radii that span millions of light-years.

Professor Alison Coil of the University of California, San Diego, and her co-authors assert, however, that many working together can do what a single supernova cannot.

Compared to the Milky Way, starburst galaxies produce stars—often very massive ones—at a rate that is several times faster. A star's life span decreases with mass; if a star's mass exceeds eight solar masses, it will explode as a supernova. As a result, exploding stars abound in any galaxy that has gone through tens of millions of years of starburst phase. Even though there can be years between explosions, these explosions nearly coincide by astronomical standards.

According to Coil, this causes winds carrying gas with a mass equal to 200 times that of the Sun to accelerate to 2,000 km/s or nearly one percent of the speed of light. That will be sufficient to force some of the gas outside the galaxy of the stars. Even more, electrons are removed from the gas.

Another peculiar aspect of ORCs at first was that they were invisible at wavelengths short enough for other kinds of telescopes to detect them. Resolving not to give up, Coil used the Keck Observatory to study ORC 4. She discovered a large region of hot, highly compressed ionized gas up to roughly 130,000 light-years away from the center of the galaxy. That is merely a tenth of the distance.

roughly 130,000 light-years away from the galactic center. Though it only represents a small portion of the detected radio wave distance, it offers a potential source for the electrons believed to be responsible for the radio emissions.

This galaxy is the result of galactic mergers, much like all other massive galaxies. Coil and her coauthors believe that, in contrast to the Milky Way, it originated from two galaxies of comparable size rather than from smaller ones being devoured. A powerful burst of star formation results from the merger, which concentrates all the gas into a very tiny area. According to a statement from Coil, "Massive stars burn out quickly and release their gas as outflowing winds when they die."

Galaxies eventually run out of material needed to create new stars. According to Coil, there was a stellar creation boom in our galaxy, but it ceased about a billion years ago.

According to simulations conducted by Dr. Cassandra Lochhaas of the Harvard & Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics, the gas outflow can generate rings that have a lifespan of up to 750 million years. Cooler gas settles back onto the galaxy within this ring. Although there may be more work to be done, the explanation seems to be correct given the disparity in time.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.