Robin's Egg Blue

I used to love this part, walking into the only pristine places left on Earth.

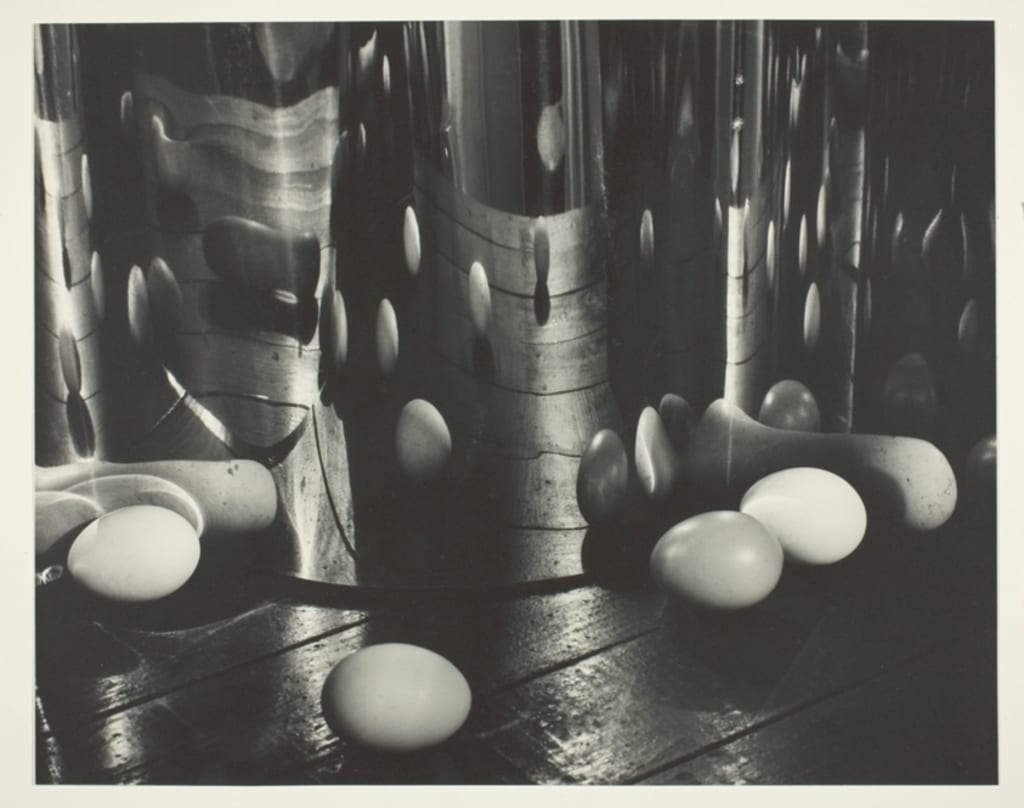

"It's eggs today," Vita says, climbing into the pilot's seat. She clicks herself in and adjusts her helmet. "We're picking up eggs."

Jordy and I settle in behind her. Until we land, he and I are just passengers.

"Eggs, huh?" Jordy tugs on his helmet, but I can tell he's still grinning under its reflective shield. "Did you know people used to have debates about them, like whether they came before the birds or the birds came first?"

I strap myself in, grabbing my helmet from its spot on the ship's low ceiling. "Huh."

Once the flight doors are shut, we're not supposed to talk, but even after Vita gives us the signal and the Marksman's engine starts to rumble, Jordy's leaned in, trying to tell me shit about eggs. "I heard they were blue."

"They're not fucking blue, Jordy." Vita's shouting over the noise of the ship, her fingers pressed tight into the worn plastic of the Marksman's yoke. "Now shut up."

"I'm just saying," Jordy pouts. "I mean, imagine it, sitting around arguing about eggs- " but before he can get philosophical about the joys of life on Earth, the red light above us switches on with a loud buzz and he snaps his teeth together. All I hear is the muffled roar of the Marksman taking off.

In a few hours we're buzzing the ground, low dips that make the engines rumble and Wilson retch in the back of the plane. Vita’s taking readings, finding the safest spot to touch down amid the pockets of radiation.

The three of us deplane. All Earthground teams are odd-numbered to prevent us from buddying up. It's mission first, then each other, then ourselves. My hand goes to the Geiger counter clipped to the left breast of my flightsuit, holding it like a rosary. Or a shield.

On Earth, the gravity is real. It's the only place my stomach feels settled. Air Ops doctors say it's all in my head, that the artificial gravity in the Orbitals is indistinguishable from Earth's gravity, but they've never been off the Orbital in their life. As soon as we deplane I can feel it. We're in what used to be Montana. Things still live here, but you couldn't call it life. Some of the rocks are covered with something like greenish rust colored mold. Our helmets have filters that let us smell, so we have a chance of picking up signals on the air, but just looking at the slime is enough to know better. We don't touch that. There are bugs, too, with hard black shells half as big as our boots.

Vita finds it first. It's about five feet in diameter, dull metal, and the bolts bust with a few turns of Jordy's wrench. Vita shines her flashlight into the hole, and we can see a green metal ladder climbing down into a concrete bunker. I go first.

All the bunkers are the same. First we pass the tactical floors, with empty missile silos and plush chairs in front of dusted-over controls. We keep our eyes shut past the next few floors, the evac bunkers, with the beds and the toys and the dinner tables all laid out, and then the huddled masses of folks who didn’t make it off planet in time. The people in here have no descendants on the Orbitals.

Everyone says the bunkers get to you worse than the radiation and by the time you go, your body's just waiting to catch up to your brain. Corpses don’t decay right when they’re sealed in a bunker, so it’s just a swollen, frozen mess, all drooping faces and clouded eyes and twisted limbs.

Finally we reach the next manhole cover, hundreds of feet below the first. We’re on the storage floor now, where all the poor souls up in the evac floors left their stuff like they could just walk it all back out again when it was over. Vita leans against a big wooden dresser. I think I smell oranges, but it’s been far too long for any organic matter to still exist. We set our yellow anti-rad tarp over the cover and seal the edges. The bolts are intact here, and it takes Jordy a while to wrench them loose while we stand in the dark.

I don't want to go first. I don't want to go down.

This dread, it’s a new feeling. Even with all the stench and the dead bodies and the sickness in my gut as I readjust to life on the orbitals, I signed up to visit the bunkers for a reason. I wanted to visit the old Earth, to walk on a planet meant rather than made for us.

I used to love this part, walking into the only pristine places left on Earth. I felt so close to our Earthbound ancestors here, walking into a room they left just for us. Like a present, gift wrapped in metal and concrete, sealed off and left with the crazy hope that we would be around to pick it up.

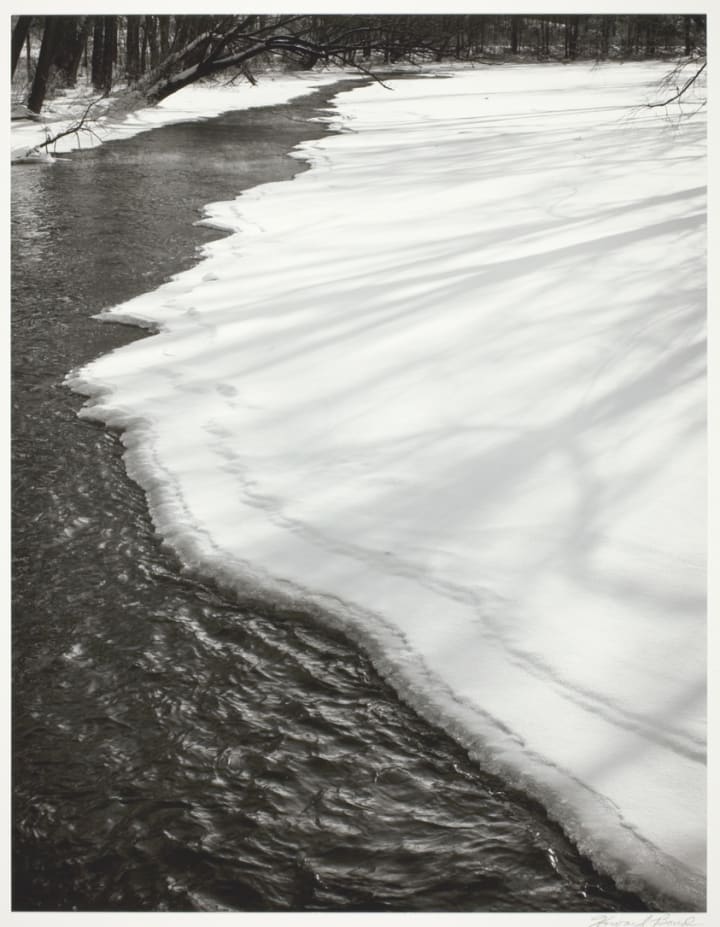

But a few months ago we were sent to the seed library. Scientists on the Orbitals had finally come up with the right soil, and lights, and whatever else– plenty of it collected by us, scrounged from Earth – and they wanted the seeds that a bunch of old Earthers had left for us to plant later. But when we got there, something had gone wrong. We knew it as soon as we landed. The Marksman skidded badly on the landing, and when we got out, the ground was slick with ice. What used to be a dry valley had filled with melting frost from the mountains above, and then it froze over again, but not before seeping down into the bunker.

We were standing on a giant frozen pond, a sheet of ice that had sliced its way down into the ground. That’s the thing about water - even when it’s gone rancid with rot and radiation, it still flows. And with the gravity on Earth, it always flows down.

Jordy and I chipped through the ice, keeping our eyes on the distorted shape of the manhole cover at the bottom of the crystallized pool. That mission took six times longer than it was supposed to, and the Geiger counters were screaming at us by the time we finished, but we couldn’t leave the seeds.

Down below, the ladder was slippery with ice. I twisted an ankle, and the pain was enough to keep me distracted from the grotesque scenes, gaping mouths with icicle teeth, little kids with delicate stars of frost on their cheeks.

I was fine, passing through the evac floors. I knew what I was getting into. It’s the price we pay for getting to breathe Earth’s air, for bringing back the planet’s riches.

What did me in wasn’t my busted ankle. It wasn’t the generations-old death and terror stacked up all around me.

It was the seed room.

Vita thought there might have been a breach as soon as we landed. She looked around at the icy landscape, the silver-white surface of the pond, and reminded us that ice expands. We knew this bunker wasn’t meant to withstand that kind of freezing. When it was built, the valley had been warm and dry in the valley when it was built.

But we climbed down anyway, down through the hole we’d chipped in the ice, down past the familiar horrors of the higher floors, down to the rescue room.

Vita was right. It had been breached. We could see the cracks in the door, the ice shoving aside the seals that were supposed to keep everything inside safe.

We kept our helmets on.

Inside, the shelves were sagging under the weight of added ice, the floor covered in a thin sheet of it. And all the seeds were destroyed. Their boxes had ruptured, their insides spilling out. Some looked like shriveled pebbles, crumbling into dust. Others were covered in mold with a strange pale glow.

We’d already spent far too long dealing with the pond, but we stayed even longer, looking for anything we could carry back with us.

We tossed over every box, pried open every case, kicked down every shelf. But there was nothing left. The ice had come in first, and then it let the radiation in to ravage the whole place.

Now there are no more seeds. We have what we have, and we’ll never find more.

Standing in front of this rescue room, I remember the sound of the last shelf falling over, its metal sides clanging against the icy floor, its ruined contents spilling out around my feet. I remember my boots crunching over dead husks and withered bulbs as we left, the cold of the ladder stinging even through my gloves, the looks on the crew’s faces when we returned far too late without a single crate for them to unload.

I don’t want to go in. My stomach is sick and not even Earth’s wholesome gravity can calm it. But it’s Mission First, and your own personal bullshit second, so I climb down inside. Jordy follows me, then Vita, our Geiger counters beeping in unison.

I wave my flashlight over the shelves full of metal containers with two sets of locks, one digital, one pins-and-tumbler. Our job is to open them on Earth to acclimate their temperatures, then seal them in our yellow anti-rad bags before carrying them up to the ship.

By now the digital locks are long dead, so Vita starts jamming at the metal locks with her pick set and soon the first box pops open. I’m standing back, pretending to scan the rest of the shelves, but I can’t help but turn around anyway when Jordy holds one up, his gloves off now.

The egg is cream-colored and covered in brown spots that I can somehow tell are natural, not mold or disease. Vita shines her flashlight through the shell and I can see a tiny bird’s body, curled and bulbous, the barest whispers of feathers like dark shadows floating in the shell.

About the Creator

Lacey Doddrow

hedonist, storyteller, solicited advice giver, desert dweller

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.