I am letting you into the secret of all secrets, mirrors are gates through which death comes and goes. Moreover if you see your whole life in a mirror you will see death at work as you see bees behind the glass in a hive.

--Orpheus (1950)

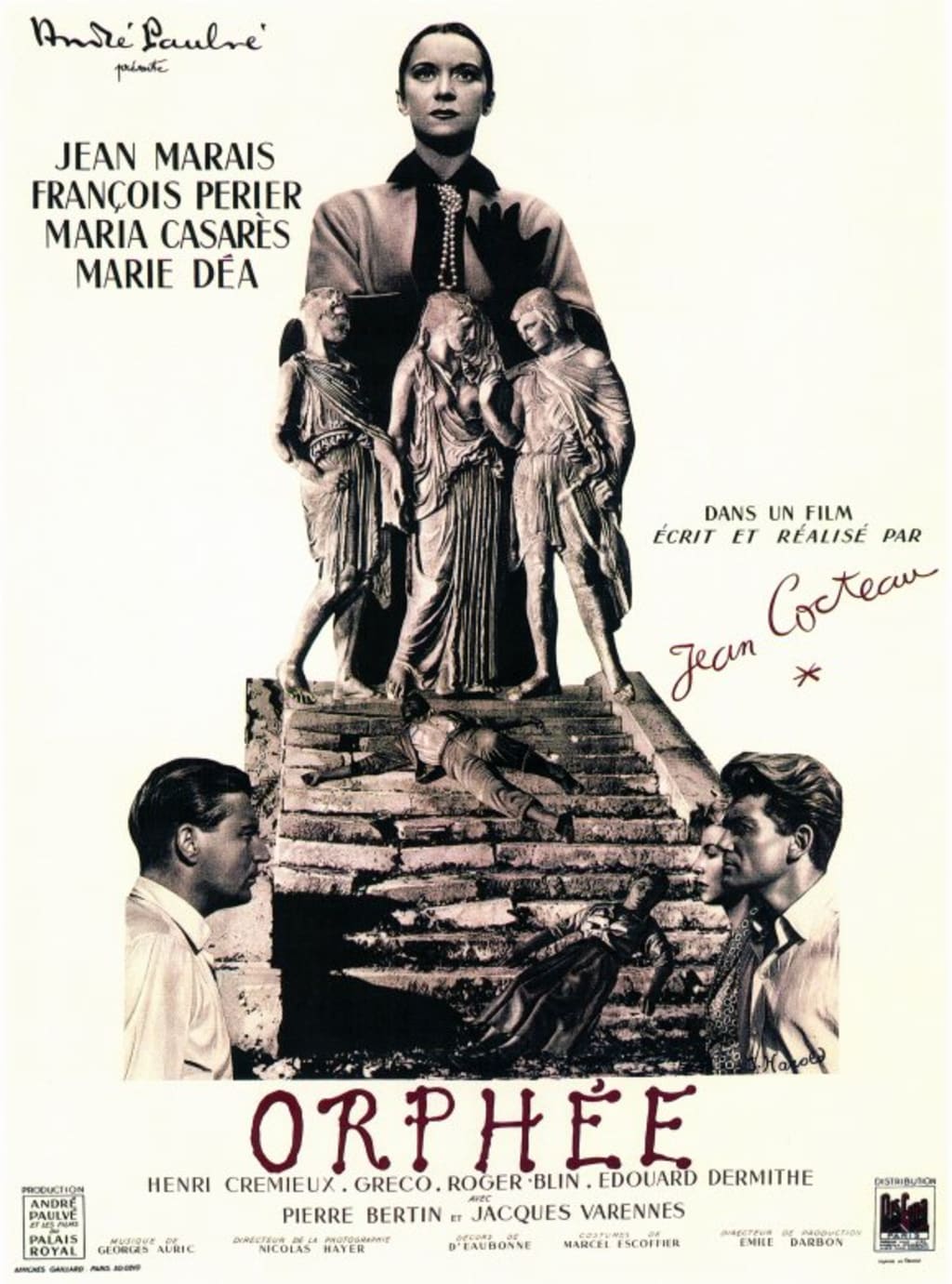

Orpheus (1950) the film is as brilliantly mythical as its source material. Starring the too-handsome Jean Marais, who was a lover of Cocteau for a time, it unfurls its cloak of magical realism, or rather surrealism, or dream-logic, as beautifully and simply and astoundingly as an image seen in a mirror--perhaps the mirrors through which the characters transport themselves into the alternate world of The Zone, and then the Underworld, simply by pointing their fingers and flying through into the crystalline liquid pool of possibilities and dreams.

It begins at the Cafe du Poetes, a place where the bored, disillusioned, and frustrated post-war youth of Paris go to reflect on a new world emerging from the old; the old which promised only fascism, bombs, bloodshed, and occupation. Orpheus is a famous poet, a precursor, apparently, to a modern 'rock star." He meets here with his publisher, who reveals to him, right away, a magazine, a literary review, with nothing printed on the pages. The viewer is led instantly to the absurdity of the scene which is to be set: "Nudisme," the publisher tells Orpheus, is what the magazine represents.

A Rolls Royce rolls up with Princess Death (Camus' lover Maria Casares) and her chauffeur, the amazing Heurtebise (François Périer). Along are two "henchman" thugs, bikers in black helmets with insectile diving goggles, white leather gauntlets, large belts cinching their waists, each wearing one-piece overalls. They cut a distinctive image, but even more remarkable is the drunken young poet Cégeste (Edouard Dermithe) who tumbles drunkenly from the car, perhaps the "bad boy" lover of Casares. He quickly instigates a brawl at the cafe, and the henchmen run him over with their bikes as planned. He is killed, thrown into the back of the Rolls, and Orpheus enters, along for the ride.

Through a negative-imaged (black to white) landscape the car proceeds, flanked by the henchman, to a chateau owned by Madam Death. Here Orpheus looks on in wonder as Madam Death brings Cégeste back to life, via the film curious "law of reversals": i.e. the film, in the oldest cinematic trick known, is simply run in reverse, to make physical actions appear as if they float, or proceed in reverse; the portals or entryways into the Zone, the "netherworld" of the invading entities, is a mirror. The mirror, of course, images whatever stares into it in reverse. Death and her henchman fly through the mirror, taking Cégeste with them to the netherworld beyond; they are, quite literally, "through the looking glass." But it is here that Orpheus cannot proceed.

The next day, he finds Heurtebise asleep behind the wheel of the Rolls. Orpheus has Heurtebise drive him home, where Eurydice (Marie Dea) is with Aglaonice (Juliette Greco) fearing for Orpheus's absence of the night before. Aglaonice is the leader of a feminist or anarchist group of some sort, and she seemingly despises Orpheus, as he likewise hates her. Eurydice tries subtly to inform Orpheus that he is going to be a father, but the perturbed poet decides he is going to bed.

Heurtebise begins to fall in love with Eurydice, almost revealing his nature as a dead man ("I committed suicide by turning on the gas," he tells her, before "correcting" himself, telling her he merely "tried" to do so), and Orpheus becomes increasingly obsessed with the weird, broken, disjointed messages that come over the Rolls radio, comparable to the messages broadcast by the French Resistance during the occupation.

These cryptic "messages from beyond" entrance him, occupying him as a poetry of the dead must, bringing him into a new consciousness by their mysterious, inscrutable nature. It is as if his subconscious mind is speaking to him in broken fragments, broadcast symbolically as a message of resistance against the boredom and ennui, the purposeless existence he is trying to escape.

The messages are broadcast at the behest of Princess Death by Cégeste. A perfect Wicked Queen from a fairy tale (the viewer will not forget that the source material is from Greek mythology), her severe black dress changes inexplicably to white, as she rages against Heurtebise for falling in love with Eurydice. She waves her hand imperiously, crashes through the mirror/portal, and disappears with Cégeste. It is then that the motorbike-riding henchmen kill Eurydice, perhaps at the behest of the Princess, and all souls disappear into the netherworld.

Heurtebise reveals himself to Orpheus and takes him through the looking-glass to the Zone, a dark, troubling ruins representative of the mind. In the literal sense representing the division between conscious and subconscious though, Heurtebise plays the role of psychopomp. Orpheus follows, a mere projection on a screen, while Heurtebise is seen distinctly in the foreground Clearly, the rules of physics are not the same here, and the point here is to suggest the dislocation of the mental process, of birth and death and rebirth. A soul with a pane of glass attached to his back goes wandering through the darkness. The looking-glass, the "portal" to this world of the Zone, of Death and Rebirth, is strapped to him, and he is trying in vain to "sell" it; but he cannot see himself.

This lost soul, a visual metaphor or digression, is but one item that swims to the foreground of the viewer's consciousness. The division between Heurtebise the Psychopomp, and Orpheus, like that of Dante and Virgil, is made a visual metaphor of descent; the poet, shaman-like, must plunge into the netherworld, represented here as the ruins of the Mind, of the Self, that may, Phoenix-like (or like the gloves that will pull themselves onto Orpheus' hands later) begin to reverse its devastation, rise from its ashes. This is an outward metaphor for the inward state of Orpheus' being; his Self in a state of ruin. (The naming of it, this Gate of Death, as the "Zone," is oddly reminiscent of William S. Burroughs' naming of it as "Interzone," in his Naked Lunch.)

It is here that Orpheus meets the weird "Tribunal of Death," that declares that Orpheus may take Eurydice back to the world of the living with him if he but take care never to "look at her again." This seemingly impossible task is agreed to, and Orpheus and Eurydice return to the world of the living.

Orpheus, while looking into the rearview mirror of the Rolls, accidentally spots Eurydice, whom he has been trying desperately to avoid looking at, and she vanishes. Meanwhile, Aglaonice and her gang pull up, intent to kill Orpheus for the presumed murder of Cégeste. Orpheus comes out with a gun he is given by Heurtebise, but he is killed anyway.

Princess Death is in love with Orpheus--we must assume the attraction is mutual; for an artist, a poet, must "die" continually, so that, shaman-like, he or she may emerge from the Zone with their real truth, their "key" as it were to the riddle, the puzzle of life put before them. It is this riddle that comes, like secret codes of resistance broken into fragments, from Cégeste's audio transmissions. It is this broken, cryptic, subconscious dialog that haunts Orpheus, dragging him toward Death, the dark backward beyond the confines of his safe, bourgeois life, to a rebirth; the eternal "Phoenixology" or rebirth, from the ashes of the beingness of the poet. It is this term, this idea, of eternal return in reinvention, that seems at the hallmark of Cocteaus' vision.

In the end, Heurtebise leads Orpheus back into the underworld, crawling against the wall as if pushed against by waves of an invisible force. Orpheus and Eurydice return to life. Princess Death and Heurtebise go together, to await their fate as becoming their judges; a form of a living mortuary, embalmed in the Netherworld where there is only judgment, censure, and No Escape.

The ruins, the darkness of the Zone--the strange soul with a windowpane is an image that swims up from the darkness, grabbing the consciousness of the viewer. (It is not a mirror, which reflects in reverse, but a true and proper pane of glass, a metaphor for looking outward at reality in its most prosaic and stilted form. What is this lost soul attempting to see?)

The world of Mirrors as portals compels--the denizens of that world, Marais, Casares, are classically beautiful in a way that is equal parts Hollywood and artistic mythological projection. Their faces are perfect models for the characters that they portray, even if Casares is appealing, partly, simply because of her dominating severity.

Orpheus is a masterpiece, a strange black-and-white dream of an earlier, more beautiful, and lost era, one which will keep the earnest viewer returning, again and again, to this particular magical cinematic mirror.

Orpheus (1950) English Subs.

About the Creator

Tom Baker

Author of Haunted Indianapolis, Indiana Ghost Folklore, Midwest Maniacs, Midwest UFOs and Beyond, Scary Urban Legends, 50 Famous Fables and Folk Tales, and Notorious Crimes of the Upper Midwest.: http://tombakerbooks.weebly.com

Reader insights

Outstanding

Excellent work. Looking forward to reading more!

Top insights

Compelling and original writing

Creative use of language & vocab

Easy to read and follow

Well-structured & engaging content

Masterful proofreading

Zero grammar & spelling mistakes

Comments (3)

Love this read❤️

You're amazing Tom

https://sites.google.com/smrturl.xyz/shsjwij/home