History of Sound Effects

Before machines, the first iteration of sound effects were created manually using fruit, glass, and other objects.

BOOM! A nuclear bomb just went off before your eyes. You feel your heart pounding, and the explosion is still reverberating in your ears, but you can’t move your body. Your eyes are glued to the screen as you sit on a cushioned chair in a cool IMAX theater. When the movie ends, you head to the bathroom and reality smacks you in the face. You’re not Will Smith and you didn’t just save the human race from extraterrestrials, but none of that matters because you feel like you did.

The special effects (FX) we experience today go above and beyond. Most people’s attention is caught on the visuals—huge explosions, horrific blood baths, and the occasional enormous green rage monster. But rarely do viewers pay attention to the sounds during the cinema. Sound effects completely alter a movie, from the intensity of a climactic scene to whether or not we connect emotionally with certain characters. These special effects can be so natural that we tend to forget where they come from—most of the time, it’s places you’d least expect.

A Time Before Screens

But what if there are no visuals? This was the struggle before television became our primary form of media, in the age of radio. Rudy Vallee entertained America back in the 30s with his hour-long radio show. It became common practice to have a little five or 10 minute dramatic skit on the show featuring some well known personality of the stage or screen. As these skits became more and more complex, sounds other than acting were added to help establish the reality of the place or locale.

On radio, we cannot see an actor enter a room as we would on the screen or stage. Instead, an audience needs an aural cue to understand when people are coming and going. These entrances and exits are often established by the sound of a door opening and closing.

Before there were machines to make these noises, the task was assigned to a bit actor, who when he wasn’t busy, would open and close the door. The door and it’s portable frame had been constructed by the carpentry department for the show. Finally, a separate sound effects department developed as the stories became more complex, demanding a variety of FX.

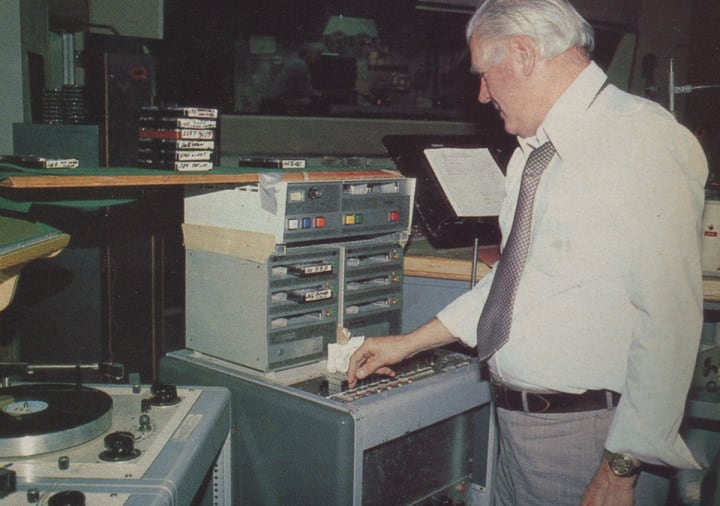

The earliest sound effects man at CBS radio in New York was one of the cast-off musicians from the silent movie companies that had abandoned the eastern coast. He was a drummer and played with a small combo that had supplied "mood music" for the actors while a sequence was being filmed. Within a few years, the dictates of radio drama would demand the services of a well-staffed sound effects department. Most shows required two sound effects men, some three... if it was for Orson Welles’s Mercury Theater, you had four.

Why all those extra people? Dramatic shows, such as Gangbusters or Arch Oboler required more than just the physical sound. The sound had to mean something, it had to convey a mood or an emotion.

Consider just a simple knock at the door. A man’s knock should be differentiated from that of a woman. Consider the knock of a man who is picking up his girl friend. Or an angry man. A good sound effects man has to have some sense of drama. He almost has to be an actor.

As a result, sound effects men began to specialize. Some were very good with comedy, but those who were polished with comic timing and audience response were not as successful with the heightened spine-tingling effects that heavy drama demanded. Many effects men from the dramatic shows had trouble developing the "feel" of comic timing. Comedy demands not only careful timing with the performer but a sense of anticipation for audience reaction. Woe betide the man who "stepped" on a laugh with his sound effect. The greats of the business usually stuck with one man who understood their style. Jack Benny and Red Skelton had their own personal sound effects men they trusted—and traveled with them for years.

Great Lengths for Great Sound

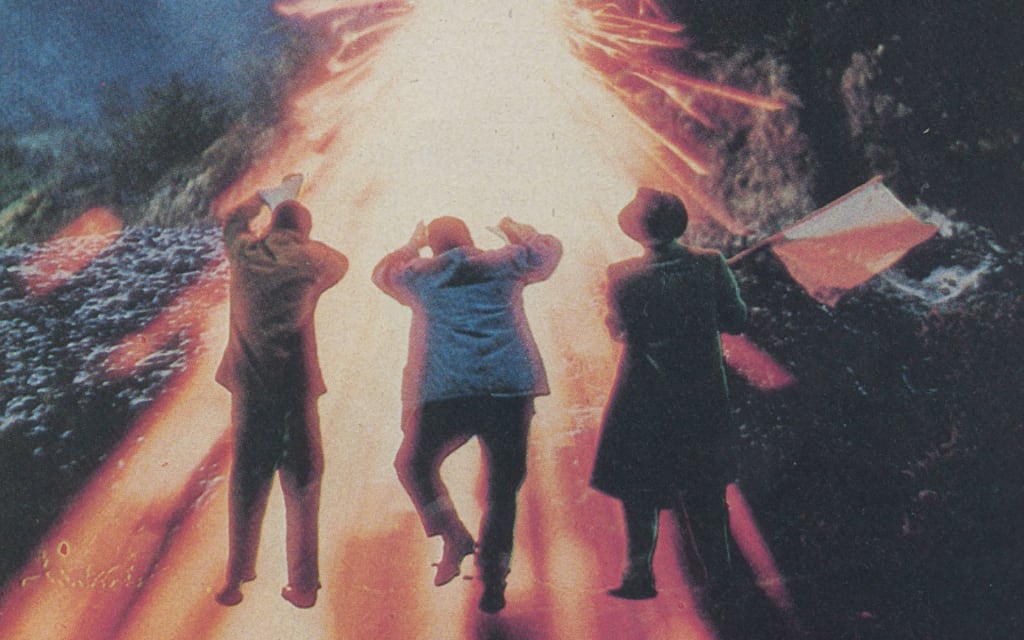

Orson Welles is among those most notorious for extraordinary demands on the art of sound effects. Welles once had an entire truckload of sand dumped on the studio floor for a foreign legion epic. He wanted a realistic effect of troops marching and moving in desert sand. An extreme measure, but it apparently helped the program. Of course, studio maintenance was faced with the problem of shoveling sand out of an eighth-floor studio.

Live effects, produced manually, are preferred by many directors and special effects men alike. The basic issue aside from control and variability of sound is quality. There are a great variety of sound effects available on disc that can be used very creatively. But in the early days, the quality of a disc did not permit very many uses. After a time, dirt would become lodged in the grooves. The record would become worn by the cuing process. The general quality of the sound would deteriorate, in contrast to the sounds that were produced live.

The search for the right sound and the machines to produce them were the challenges faced by sound effects men during the golden age of the 30s and 40s. The sound effects men usually got a script for a show about a week in advance; In that week all the necessary sounds must either have been pulled from stock or created. If an effect were a common one, rain for example, the manual device used to create it would, over the years, have become quite sophisticated. A good rain machine could generate just about any kind of storm from a light shower to a full-fledged gale.

Such a machine, after many years of refinement, might give very little clue to its purpose from its physical appearance. One rain machine, at CBS for example, consisted of a box about the size of a small television set. At the top was a hopper which contained about 10 quarts of bird seed. Below the hopper was a motor-driven turntable. The seed would fall quietly to the turntable as it spun. The speed of the turntable could be controlled in such a way that the seed would be flung off the turntable in varying degrees of force. The seed could also land on varied types of material, which would affect the sound of the "rain." Commonly, these materials were either a piece of tin, a piece of parchment, or a piece of wrapping paper. With the addition of the sound of wind, you had a storm—made to order.

Some manuals are miniature versions of the real thing—doors and windows for example. Some studios use small scale doors with various kinds of locks attached to give the sound of the key being inserted, the latch turned and the door opening. Other studios avoided such small-scale hardware—they always built everything to size, to be sure of the authenticity of the effect. Such decisions are made on the basis of studio acoustics and the nature of the microphones used.

Sidney Brechner was the sound effects hero of radio station WJR in the late 30s and early 40s, for their classic show Hermit’s Cave. Hermit’s Cave was known for its unusual effects. On Lux Radio Theater you might have an execution by hanging and you would hear the trapdoor give way, but that would be it. But Hermit’s Cave had everything. "We made a big ado about it—you’d hear the trapdoor, the snap of the neck, and the creak of the rope as the guy swung in the breeze," reported Brechner.

Places You'd Least Expect

Mr. Brechner took great care and pride with his hunt for just the right means to create the perfect effect. One episode required the sound of a man walking across a nest of spiders. "It took me a week to find the right sound, and I discovered it accidentally at that. I was visiting my mother and eating some grapes from a bunch on the table. I dropped one on the floor and in the midst of trying to retrieve it, accidentally squashed it. Well, "I stopped cold. It sent chills up my spine, but it was just the sound that I had been looking for! Bunches of grapes were placed in a large wooden tray for Mr. Brechner to walk over with the microphone only inches away. The sound of the skins splitting and the crunch of the tiny seeds gave just the right touch to Hermit’s Cave.

Years later, Mr. Brechner happened to actually step on a spider and he reports that the sound was entirely different from the grapes, but not nearly as effective.

Sound effects on radio at that time were precision affairs. It had to be right the first time, since the shows were broadcast live. There were, of course, accidents. Occasionally an accident might actually improve an effect.

"One episode of Hermit’s Cave involved this weird doctor who enjoyed cutting people's fingers and toes off-sawing them off. To get the right sound I used pork chops (they were pretty cheap back then) and a small coping saw. During rehearsal, I was too damn busy to realize how ludicrous I must have looked creating this sound. But all at once the absurdity of the situation dawned on me—holding this pork chop with my dirty hands and sawing away as if there was no tomorrow. I started to laugh. I was only inches away from the microphone."

"The director didn’t think it was funny at all and over the earphones was telling me just what he thought of such stupid carelessness. They had to change the last part of the script. One of the actors added a line to the effect that 'wasn’t it funny how every time the doctor cut somebody's fingers off he had that wild laugh.' It was the only time I broke up on the air, but those things happen."

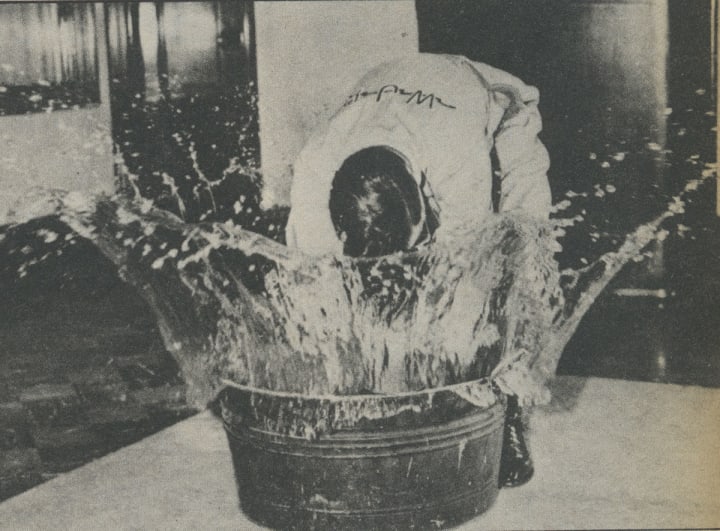

A great variety of devices were used to create an even greater variety of sounds. Consider the famous Orson Welles pickle jar slowly unscrewing in the depths of a studio toilet bowl to create the ominous grating of the Martian war machines in the world famous War of the Worlds.

Rhythm was the secret used to create realistic effects with coconut shells (used for horse's hooves), as it was with most manual effects. Twisting celery with the proper rhythm, held close the the mike, generated a very effective strangulation sound. Of course, in real life there probably isn’t any such sound, save for the sounds of the choking victim trying to breathe. But for the radio, celery could be used to create a very chilling effect. "You use a very slow twisting of the celery, close up to the mike. Throw in a few appropriately timed gurgling noises, then give the celery a sudden snap and you’ve got it."

Many of the devices used for sound effects were used universally. The NBC tour of Rockefeller Center was a must for any new sound effects man, as part of the tour was a behind-the-scenes look at their department. Ideas quickly spread.

Visually stimulating sound effects are the hallmark of media entertainment. The golden age of radio gave sound effects a new mantle place. They now created the visual image in the radio listener’s mind instead of giving reality to silent movies. The same methods used for radio drama in the 30s and 40s are still used today—from re-creating the cry of a baby or the thunderous stampede of elephants to even just a fart. If it weren’t for sound effect artists, we would never be able to interpret or connect to media in the way we do today.

Recommended Reading

This article highlights a few of the more common and more bizarre strategies to sound effects. For those seeking to delve deeper into this craft, The Sound Effects Bible will walk you through a wider variety of effects and how to create them.

The Sound Effects Bible provides readers with a complete guide to creating, recording, and editing sound effects. With sections on microphone selection, field recorders, digital audio, Digital Audio Workstations, building a Foley Stage, designing an editing studio, and much more.

About the Creator

James Lizowski

Spends his days making his own Star Wars figurines. His craft has driven him to look towards the future, drawing inspiration from past technological advances.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.