Galileo Galilei’s "Dialogue on the Two Chief World Systems" on Trial

In 1632, Galileo was tried by the Catholic Church for his writings about Copernican astronomy

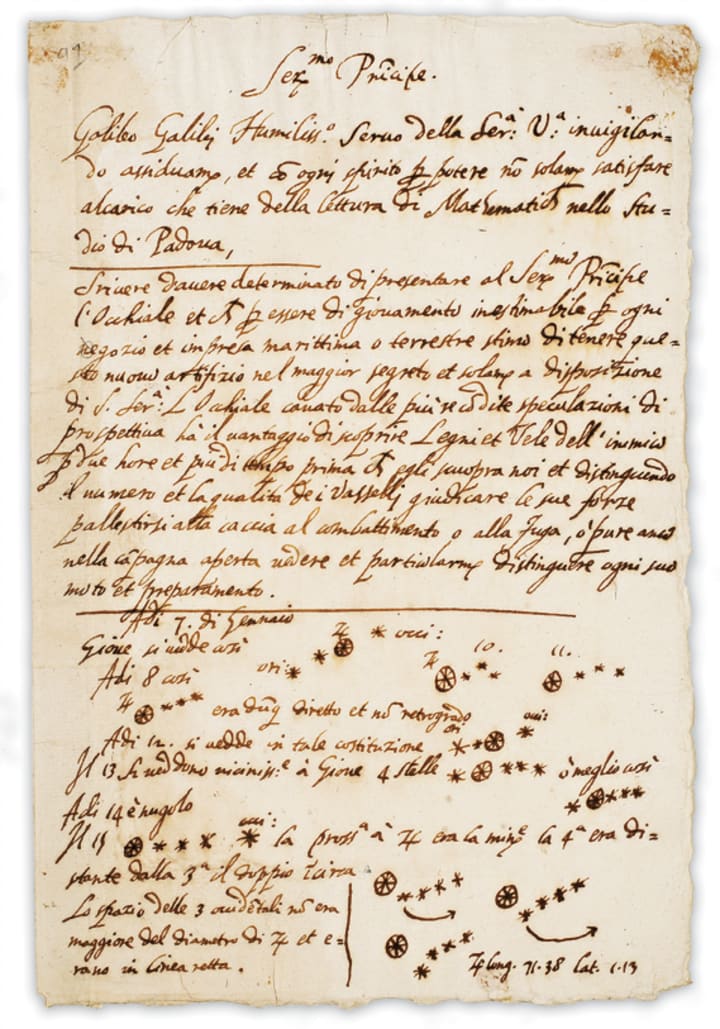

In the introduction to the trial letters, Thomas F. Mayer writes that the trial is similar to a myth and that “ This is not at all that surprising, since the trial has almost never been studied as a legal event” (1). A reader might ask why the trial is not being studied as a legal event. Also, Mayer points out: “ Almost equally important, studying the trial more closely takes some of the heat out of the often violent debate over the rights and wrongs of what happened” (1). Federico Cesi, an ambitious grandnephew of a cardinal, banned members of religious orders from his club called Academy of the Lynxes. He had become a patron of Galileo’s and continued to insist the prevention of members of the Jesuit order from entering the Academy (2). Galileo disaffected the Jesuits, which helped lead to his downfall (2). The Jesuits began as a collection of approximately 20,000 teachers and missionaries who ran various academic institutions. These universities often were home to the the world’s greatest scientific instructors (3). Cesi died before he was able to complete publishing Galileo’s Dialogue (45). Although he was instructed not to use interpretations of the Bible in his explanation of Copernicus’ ideas about astronomy, “ [Galileo] acted as he always did, ruthlessly pursuing an agenda of liberty for philosophy and fame for himself” (3). Cardinal Conti was a lawyer instructed by the Jesuits, his ambition of running the papal state threatened the position of his nephew, and he remained outside of Rome for a long time. Galileo asked the advice of Cardinal Conti because one of his servants was a scientist whom he had known previously (41).

The Roman Inquisition had no jury and also held the accused to be “guilty until proven innocent” (7). The Inquisition conducted secret meetings and did not allow the Notary to be present during them, and only providing him with notes on the proceedings, making his job of binding records even more difficult (6). Pope Paul and his assistants worked all day on Saturday, in mail administration related to the trial (5). The most important official working for the inquisition was the Commissary, which in this particular case means “ representative” or “stand-in” (5). The Notary was in charge of transferring information into the decree registers from the notes that he had taken on congregations. His assistants were very bad at their job, perhaps because they were not paid enough (5). This gnomonic gap in information may partially explain why the trial has a myth-like quality, lacking certain details that could give it depth.

A troublemaking Dominacan preacher, Niccolo Lorini questioned Galileo’s assertions about the planet earth because it competed with what he considered to be God’s work (43). In a letter to Curzio Picchena, Galileo writes:

What I have done can always be seen in my writings, which I keep for that reason, in order always to be able to close the mouths of the evil-willed, since I can show how my dealing in this matter has been such that a saint would not have dealt with it neither with more reverence nor more zeal toward the holy church, which my enemies have not perhaps done, who have not avoided machines [machinations], lies and every diabolical suggestion, as with a long story their serene highnesses and also your lordship will understand in time (101).

Galileo compares his handling of the damnation of his work to that of a saint, and states that the arguments of his adversaries depended upon deception and dishonesty.

In an excerpt from the congregation’s report in mid-August: “ In 1630 Galileo brought his manuscript book to Rome to the master of the Sacred Palace in order to be reviewed for the press and the Father Master gave it for review to Father Raffaelo Visconti, his official substitute and professor of mathematics, and having emended it in many places he [Visconti] was on the point of giving it his affidavit in the usual form, if the book were published in Rome” (119). In another excerpt, the sixth section of the body of Galileo’s crime is described as “ Asserting and declaring badly some equivalence between the human and divine intellect in comprehending geometrical things” (120). In a letter to Giorgio Bolognetti, the papal ambassador in Florence, Francesco Barberini reports that the Master of the Sacred Palace failed to make sense of the Dialogue but showed concern that the book might be circulated should it contain errors (123).

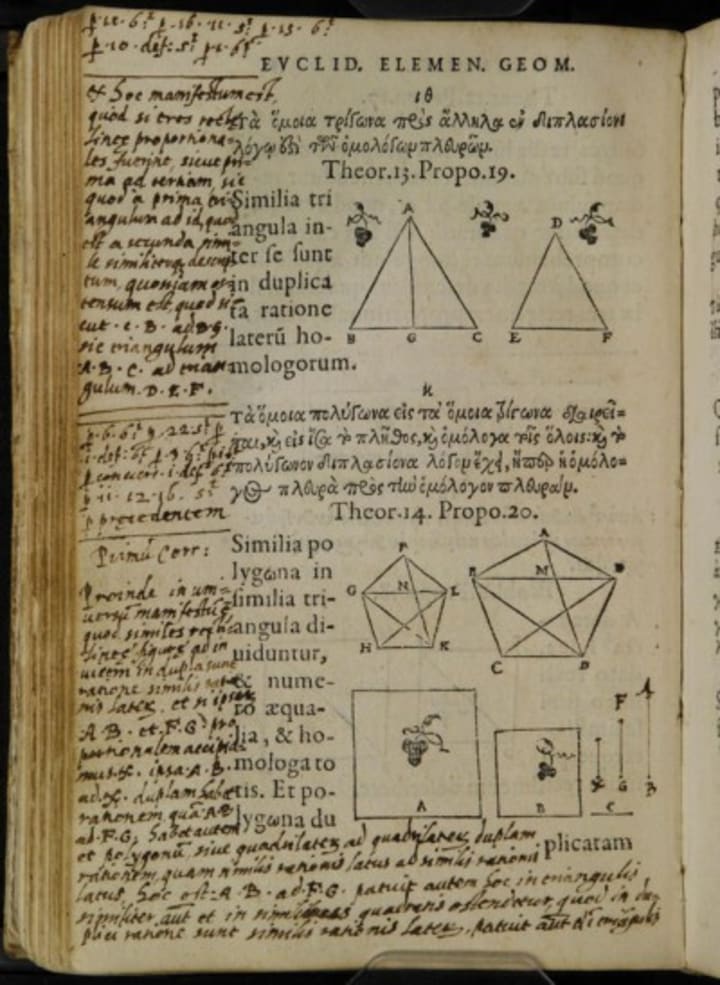

Regarding the movement or stillness of the earth, Beneditto Castelli writes to Galileo that “ It has been well looked into by sacred writers but not decided and taught, since it means nothing to the salvation of souls” (126). Further, he describes conversing with Father Master Pier Dionisio Veglio, a geometer and astronomer who, after reading Galileo’s Dialogue, suggested that all writings concerning the spherical nature of solar system were childish and should be burned. A student of this Veglio was in agreement. Galileo’s bewildered explanation of the discourse on his Dialogue was fairly dramatic: “ But it truly came to me unexpected that the hatred of some against me and my writings solely because they partly put in the shade the brilliance of theirs would powerfully impress on the superiors’ most holy minds that this my book is unworthy of the light” (127). Mario Guiducci wrote to Galileo in March of 1633 of Lord Cardinal Ludovico Capponi that he enjoyed the content of the Dialogue, such that he was disappointed in his ignorance of the work of Euclid, and would have liked to have deeper understanding of it (153).

A term used in describing Galileo’s trial was particular, meaning “ ‘[P]articular congregation,’ a small body of Inquisition often assigned to investigate a detail” (4). In the formal proceedings of Galileo’s First Deposition, he responds to the statements made by the cardinals by saying, “ The occasion to deal with the said lord cardinals was because they wanted to be informed about Copernicus’s teaching, his book being rather difficult to understand by those who were not educated in mathematics or astronomy” (157). In a letter to Andrea Cioli, Francesco Niccolini describes the deluxe suite that was given to Galileo and how it was not in any way like a prison cell reserved for the common criminal. During the formal proceedings of Galileo’s trial, Zaccaria Pasqualigo’s asserts that “[B]ecause [Galileo] produces his [Dialogue] in such a fashion that also many who understand the mathematical sciences remain persuaded” (167). The extent to which Galileo’s work was accepted by the scientific community of the time was problematic to the critics of his time.

Mayer, Thomas Frederick. The Trial of Galileo: 1612-1633. University of Toronto Press, 2012.

About the Creator

Sabine Lucile Scott

Hi! I am a twenty-nine year old college student at San Francisco State University majoring in Mathematics for Advanced Studies. I plan to continue onto graduate school in Mathematics once I am finished the plethora of courses which remain.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.