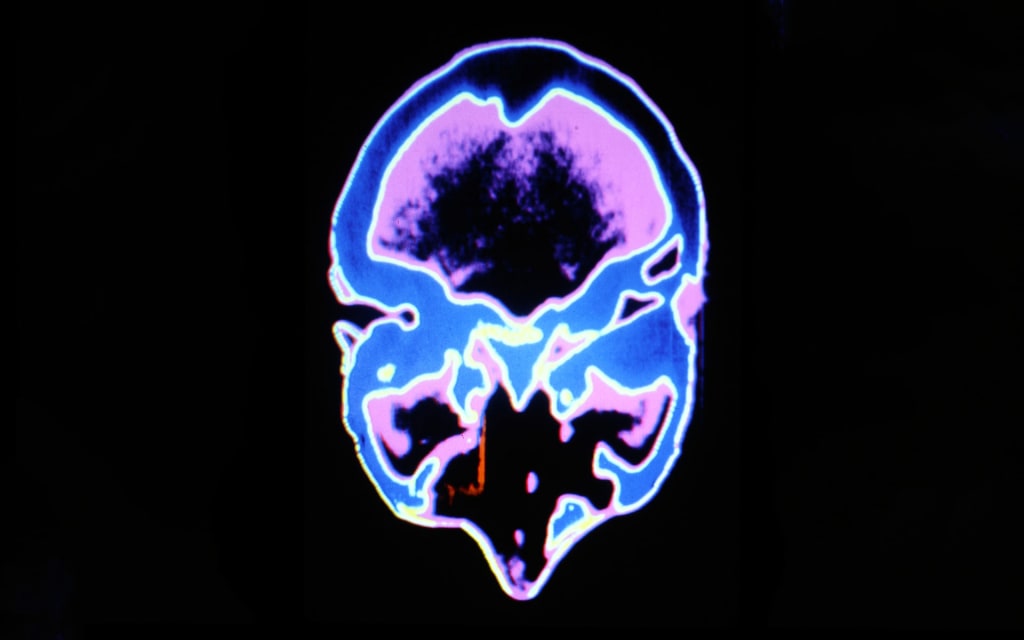

Do Language and Emotion Affect Health?

Your health is greatly impacted by the language you use to describe it, and the emotion that this language evokes.

Some years ago, when I was a little younger but just as peculiar, I was a general surgeon more interested in why people got sick than in cutting them—and equally interested in why they got well. Eventually, I decided that if I were to get any of my crazy ideas accepted, I'd have to become a psychiatrist. So I started hunting for a psychiatry residency. I was interviewed by one eminent gentleman and incidentally expressed my belief that anger and depression were important mechanisms in the induction of cancer. He sneered, not very politely, and said, "Every weekend we get at least a dozen nuts in the emergency room who have figured out what causes cancer." I asked, "What do they say?" His reply, which I treasure, was, "We ignore them... we have better things to do."

Better things to do? Yes, I suppose so. From his point of view we already know that cancer is caused by this, that, and the other thing. The list grows daily—just watch your newspaper.

Although I will concede that constant exposure to soot does relate to carcinoma of the scrotum among chimney sweeps in England, I have difficulty accepting the idea that everything I like is carcinogenic. I am told, in numerous scientific announcements, that maraschino cherries, barbecued meats, the water I drink, and the air I breathe are all going to lay me low. And that's not all. Eggs, sugar, milk, cream, butter (my wife and I probably eat several tons of these deadly items per year, to the accompaniment of shrieks from our friends) are all denigrated by the utmost authorities. Leaving the worst for last, tobacco, the sin of sins, as well as coffee, the mainstays of my existence and functioning—well, they say you would be safer sitting all day playing Russian roulette with a forty-five!

This all sounds very sensible, but it nonetheless leaves me entirely dissatisfied. Some people smoke and get lung cancer, lots of people smoke and don't get lung cancer. My questions remain unanswered: why do people get sick? And why do some stay sick? And why do people get well, and if they don't, why not?

We Want Answers

Are these impossible questions? Physicians, of course, have all the answers unless you look closely. They have names for all the known diseases—sometimes, lots of names– and people do feel some relief when given a name for what is bothering them. Afflicted individuals pestiferously return to the doctor or chiropractor or, lately, to an infinite variety of gurus and complain that they feel no better.

We have doctors whose model for "diseases" are due, they say, to "real" organic causes. We also have the psychosomaticists, most of whom give a fairly clear message that, basically, it is all in your head. Sandwiched in between is a new breed of patient, semi-antiestablishment, who enjoys health food a lot. This group is uncomfortable with partisans of either of the former approaches and is searching out "alternative treatment modes." In former days, people who employed such therapies were called quacks, but now they seem to be practicing holistic medicine, acupuncture, acupressure, transcendental meditation, faith healing, and who knows what else. For those who want something to smear on, shoot up, or ingest, we have royal queen bee jelly, Laetrile, Krebiozen, and other varieties of rather more concrete treatments.

The really weird thing is that all of these work—sometimes, somehow, and to variable degrees. But people still get sick. As soon as we stamp out one disease, a worse one appears. Sometimes without stamping one out, a new one starts in it almost seems as if we must have disease. We have to get sick, one way or another, in spite of, and more frequently now because of scientific advances.

"Iatrogenic" is an increasingly popular word for the trouble you get after you go to the doctor. There are even people who are hideously ill yet—to paraphrase Shakespeare—prefer to keep those ills they have than fly to medical management they know not of. Are there medical advances? Yes, of course, but if you add them all up, particularly here in scientific America, we humans should not be having high blood pressure, obesity, coronary artery disease, and on and on. I won't even mention the unconquerable head colds, sinusitis, and, in the young, ear infections, tonsillitis, acne vulgaris, and much, much more.

Yet all the same, the clues abound. Once in a great while you encounter an individual who has managed to live to an advanced age, who is not sure what doctors are for, since he or she never goes to see one, and who dies—usually while asleep–without assistance from contemporary diagnosis or scalpels. Others, it seems, are the opposite, always having something wrong somewhere. They look at you blankly when asked when they last were well. Most people are somewhere between these two extremes, having alternating periods of health and sickness over the years, the finale being some type of unsuccessful major medical ritual.

Finally, there are the so-called cancer miracles, which do actually happen, however rarely.

Thoughts, Language, and Emotions

All this seemed clear to me in 1960 or thereabouts. I imagined that thoughts, language, and emotions had a good deal to do with illness. (For this was considered quite disturbed by many of my associates.) The crux of the matter was that each patient, with all his or her problems, should have exactly those problems. The more deeply I went into that person's behavior, thinking, and lifestyle, the more sense it made. Most particularly, it seemed that unhappiness, of whatever type, was an integral part of getting sick.

I recall a charming young woman afflicted with a relatively common though obscure condition called "idiopathic cervical adenitis." This means that she had swollen glands in her neck that were tender and bothersome; no one could figure out why. She had seen dentists, throat specialists, and internists to no avail. I was treating her for something else but became interested in her neck difficulties, and we talked a good bit. She was a lonely girl, rather prudish, slightly over religious, and very inexperienced in the ways of the world. She found most males overly aggressive in sexual matters, so never dated. Suddenly, while she was still my patient, a man in her office started to show considerable interest in her. Within a few weeks she was a changed girl—sparkling, alert, wide-eyed. And, fascinating to me, the chronically swollen nodes in her neck completely disappeared. This lasted six weeks; then she found out that he was married, happily so, with a gaggle of children. Literally within a matter of days, the nodes returned, accompanied by their associated miseries and distress.

To my amazement, I was soon able to find similar factors in every patient I saw. Some cases, as the one above, were obvious. Others were extremely obscure, requiring long periods of observation. Many patients totally denied carefully concealed emotional pains, while others were completely unaware that they were unhappy, feeling this to be their "normal" state. I gradually learned ways to get through to them and in the process learned how devious the human mind can be.

At one point I began to realize that the puzzles of human illness were not insoluble. I gave occasional lectures (and was considered something of a quack), but mainly kept working with patients and studying in all directions. I learned of Darwin's 23-year silence and so kept silent—for the most part. The exceptions were my frequent letters to the editor and book reviews, each with one or two of my own ideas tucked in: a comment on wedding-ring dermatitis, a brief discussion of the emotional feedback of shoulder posture, a hint that schizophrenia might be caused by disturbed thinking (instead of being the cause of disturbed thinking), and so on.

Defintions

But the climate gradually changed, and now I no longer wish to avoid open publication. So, let's state a few basic definitions and postulates and then proceed:

- There is no such thing as a fact any verbal statement is an opinion, no matter how labeled. For example, any statement can be called either an opinion or a fact. If you call it an opinion, you bear in mind the possibility of error. If you call it a fact, you are neurotically expressing a belief that the statement is gold-plated, never to be questioned, and, more important, you are turning off your thinking machine as to that item.

- Objective knowledge is a myth: all "knowledge," being based on biases in "perception" and "cognition," is subjective and emotionally determined.

- There are only two emotions, like and dislike: all others are compounds of one of these plus a personally formulated comment about "reality" (e.g., "lonely" = I am all alone now + I do not like being alone).

- Anger and depression are not separate emotions. Anger is: "Reality, as I seem to perceive it, does not match my fantasy of how it ought to be, but I think there is something I can do about it." Depression is the same, except... "but there is nothing I can do about it."

- (This one is critical). Negative emotions are associated with unnecessary disturbances of bodily mechanisms, proportional to the duration and intensity of the negative emotional state. Such reactions are not limited to a particular organ. All bodily organs and cells express their response to such brain states in various ways. If you are angry or depressed about your job, your stomach acids will either go up or down; your blood pressure will go up or down; your glands will increase or decrease their functioning, etc.

Consider the concept of "stress." There are, from my point of view, two reactions to stress. If it makes you miserable, your body will have all kinds of deleterious reactions. But if the stress is enjoyable— pursuing a not-too-willing member of the opposite sex, for example—the stress will make both you and your body function better than ever, up to the limits Mother Nature herself has installed.

Is there, then, a significant possibility that anger and depression, rather than being normal and necessary concomitants of human existence, are the long-sought variable factors in the development of all human diseases, both "mental" and "physical"?

This idea, bizarre as it sounds, has been for me of enormous clinical utility, and I do believe it has enormous potential for the welfare of everyone. It means that you can do something to try to avoid getting sick. It also means that if you are sick, there is something you can do to promote your recovery. And, of particular interest to the medical profession, it eliminates the idea that there are "untreatable" diseases and affords new approaches to the major human scourges–cancer, coronary artery disease, and hypertension, to name but a few.

This entire subject is, of course, incredibly complex if my ideas seem simplistic, they are not—I have seen them work when all else failed. But before going on, I would like to insert a bit of personal history. In medical school, where I was able to listen to what I was told—and to repeat it back in test situations—they told me: “Measles is caused by a virus, and that's a fact." In my head recorded, "They say measles is caused by a virus, and that is an opinion." Some of their "facts" seemed potentially useful, so I decided to hang on to all of them in case they came in handy. Some did; a lot didn't. So I became a doctor and later a surgeon and later a psychiatrist, but always with a head full of questions.

I became extensively concerned with the state of mind of my patients, both before and after surgery. At the same time, became deliberately introspective, trying to look into my own head to see what was going on and how it worked. The net result of all this was an enormously changed state of mind on my part concerning the nature of my patients and their illnesses and how to care for them. I found that scientific medicine alone was not enough, and that my intense emotional involvement with the patient was part of the treatment. Further, I found that anything I did to make the patient feel better helped him to get better.

I continued to practice "good" medicine by eliminating treatments or medications that in some way made the patient feel worse. I also added anything that had a definite "positive placebo" effect. Critical to all this was my belief that I could help the patient, no matter what the diagnosis. Equally critical was my ability to make the patient feel the same thing. The results? My patients did better, recovered sooner, and had fewer complications. Even people hopelessly ill or dying showed definite improvement in the quality of their remaining existence.

We Got Answers

Now let's start over and try to answer a few of those impossibly difficult questions.

Why do people get sick?It is not due to "physical" or “mental" factors but to the sum of all factors: physical, mental, emotional, and environmental, past and present. Careful observation, however, suggests that negative emotional states of some type are almost always present and contributory. Further, it is my opinion that what actually happens to people is not as important in producing illness as what they think happened is. In other words, if something bad happens, you don't have to get sick if you can avoid getting miserable about the situation.

Why do people get what they get when they get it?This is the problem of psychosomatic specificity (e.g., what all the people with certain diseases have in common). If you consider everything that has happened to an individual since conception (or before), everything others have said to him or her, every thought he or she has ever had, plus everything that has been happening in the universe during the corresponding time, it becomes obvious that each person should, at any instant in time, have exactly what he or she does have. And when you look closely, you do discover that people with similar diseases have similar patterns, most particularly in their thinking.

The American Cancer Society provided me with an excellent example of the disadvantages of "normal" thinking. In an ad, underneath a series of photographs showing a little boy and girl holding hands, the caption read: "Little children shouldn't get leukemia." According to me, that message has a number of less than desirable effects: it makes you angry or depressed, and more seriously, it does not lead to open thinking. Try this instead: "Since certain children do get leukemia, if we understood all the factors, it would become obvious that those children should have gotten leukemia."

This phrase opens your mind to an infinity of questions, a few of which just might be important in seeing what the processes actually are. The problem is, of course, in the word "should." In the first case, it means "it would be nicer if," but it is expressed in a psychotic manner, e.g. contrary to reality. In the second case, it means "it is appropriate that" and is more in accord with so-called reality as we perceive it.

Does this mean that all diseases are mental?No. I say that mind processes (which means the functioning of the total brain in the body) are indeed part of, but only part of, getting sick or recovering.

Then how we think does contribute to getting sick or well?Exactly! And this brings up the other problem, equally complex, of just how our language affects our perceptions and behaviors. I will only indicate here that: (a) language is full of traps, (b) there is no single right word to apply to anything or any process, and (c) each word you use as a label for something makes you see it in an entirely different way. Say "I am free" and mean it. Say "I am a slave" and mean it. Then alternate—and watch your feelings.

Having arrived at that point, perhaps we can now start talking about the diseases so prevalent in our day, and what, perhaps, each of us can do to avoid getting sick, or if sick, what we can do to restore ourselves to health.

A Look at High Blood Pressure

Obviously, we cannot discuss here all the major diseases so I picked one that is now practically epidemic and truly a major public health problem: high blood pressure. It wrecks hearts, kidneys, and other things and leads to one of the most tragic of human conditions, a stroke. Worse, the incidence is currently increasing at a horrendous rate. A few cases are due to certain peculiar "physical" lesions, but the vast majority are what is called "idiopathic" or "essential" hypertension, which means the cause is unknown. Some doctors feel that it is inherited or "genetic" (loosely translated, "good luck, buddy"). Others blame diet, salt, your job, your wife or husband, etc., etc., ad infinitum.

A few researchers, particularly those into biofeedback, currently hold that anger is a cause. They are close, but not close enough. One person came much closer, back in 1952. While studying the attitudes of patients with a variety of diseases at New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center, Dr. David T. Graham found that those with hypertension "felt that they constantly had to be ready for anything." (The reference is: Psychosom Med 14:243-251, 1952). This was a genuine, gold-plated clue, though his work was put down, ignored, and largely forgotten... but in a few moments you will understand the significance of his finding.

Remember, I called all diseases "behaviors," in other words, things that people do, and hypothesized that if something was wrong, then there was something that the person was unhappy about. When I found a patient with elevated blood pressure (140/90 mm/Hg or more), I said to myself not “He has hypertension" but "He is hypertensioning." While doing a physical examination I would keep talking to the patient while regularly checking his blood pressure. I discovered could make that pressure go up or down—not by what was saying or asking, but by what I was making happen in the person's head. Naturally, I found patients with no anger who had high blood pressure and people with horrible jobs and nasty spouses who did not have high blood pressure. But the ones with high blood pressure did have what is called "anxiety." There, with a little conniving, is where I found an answer... not the only answer but one that works.

Anxiety is a common term and one of the mainstays of psychiatric theory. It is defined as an emotion. It isn't. It is a compound of two things: an awareness of the existence of ambiguity and a depressive reaction to this awareness. More simply, it means that you don't know what's going to happen, and you are unhappy about this. And this is exactly what I consistently found in people with elevated blood pressure—that they did, indeed, have an incredible intolerance of ambiguity. I have described a person with high blood pressure as a person with his head in a neck brace—so he can't look up—who must walk through a forest on a narrow, winding path, and who knows that up in one of those trees there is a very large and very hungry boa constrictor waiting just for him.

Do You Get The Picture?

The awareness of ambiguity is not a bad and unpleasant thing but a good thing, a major survival mechanism. It is to be welcomed as a warning sign saying, "Attention! Be careful!" And we learn that with proper attention to this warning, great success will come our way in getting things accomplished.

For example, suppose you are driving the freeway. The traffic is heavy and you begin to feel jittery. You don't know what that turkey in the next lane is going to do. You have several choices. You can keep getting more nervous and/or angry. You can get off the freeway and pop a Valium or you can have a cocktail which will seem to resolve your problem but will not improve your chances of reaching your destination. Or you can drive carefully and watch everything around you like a hawk. (There are, of course times when a brief coffee stop or a rest or taking surface streets is a bright idea).

We have looked carefully at the thinking behind high blood pressure and found that this thought pattern is not unique to the hypertensive person but common to all people. The person with high blood pressure just does it more and better. Further, it means that the common garden variety of hypertension can be prevented—or can be treated while it is still “labile" (when pressure goes up under stress and down when the stress is over). We can continue now and list those things that advise not only for the person with high blood pressure but for the treatment or prevention of any kind of problem:

- Learn to quickly identify the onset of anger and depressive feelings in yourself.

- Pick something you don't want to have happen to you—a heart attack, an ulcer, the removal of some organ—and when something happens that would normally make you become either angry or unhappy, ask yourself if giving in to these negative feelings is worth the disease price you'll have to pay. If the answer is yes, seek professional help, preferably from a therapist who is not depressed.

- Discontinue any medications that are central nervous system depressants— this includes many of the drugs now so frequently prescribed.

- Use alcohol only in trivial amounts: It's probably the worst brain depressant we have.

- Start observing other people: their postures, their choice of words and tones of voice, pitch, and stress. Study the reactions of others and try to guess what is going on in their heads. And then watch yourself. A good item to start with is shoulder posture: down and forward is depressed, up and forward is hostile, up and back gives you the feeling that you are working toward the control of your own reality. Try these postures alternately and observe your own reactions and those of others to these postures. You'Il be amazed.

- Decide each morning that throughout the day whatever happens will not make you as angry or as unhappy as it would have the day before.

- Get rid of the words "got to," "have to," "should," "must," "ought to," and that old favorite, "willpower." You can't do anything except what you want to do—so enjoy it.

There are obviously many more guidelines that I could list and undoubtedly many more I have not seen. But these are, at least, a start in the right direction. Believe it or not, such behaviors help with the “real" medical problems; whether abnormal gastric acidity, elevated cholesterol, or a pimple on your nose is your particular problem.

And for the curious—what were the results of this approach to hypertension in my practice? Previously uncontrolled patients could be brought down to normal levels (below 140/90 mmHg) utilizing only thiazide diuretic medication, and thus avoiding the complex-acting and unpleasant ganglionic blocking agents, many of which, by the way, have depressing effects. Many patients learned that their "early" hypertension could be eradicated. Typical of one of these was a person who for years had been found to have elevated blood pressure upon each conSultation with a new doctor. And the blood pressure would fall with rest, reassurance from the new doctor, and the like. These patients, I believe, are the pool from which later fixed hypertensives are developed: other doctors claim that this entity is meaningless and no risk. I do not agree. Finally, as far as results, when I closed my practice I had no paralyzed patients lying in nursing homes waiting out the dreary years.

It is my carefully considered opinion that negative states, particularly anger and depression, are critical components in the development of all the most common medical and psychiatric problems we can get—and this includes cancer. And I do believe that by learning how our heads work and how to work our heads, we can all learn to live longer, healthier, and happier lives.

Esther N. Sternberg examines the link between mind and body in The Balance Within: The Science Connecting Health and Emotions. Filled with first hand accounts of the discovery between health and emotion, this novel is full of fascinating information for those who wish to understand body and mind as a whole.

About the Creator

Futurism Staff

A team of space cadets making the most out of their time trapped on Earth. Help.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.