Did The Pope Support Malleus Maleficarum?

A look into the Church's role in the Hammer of the Witches

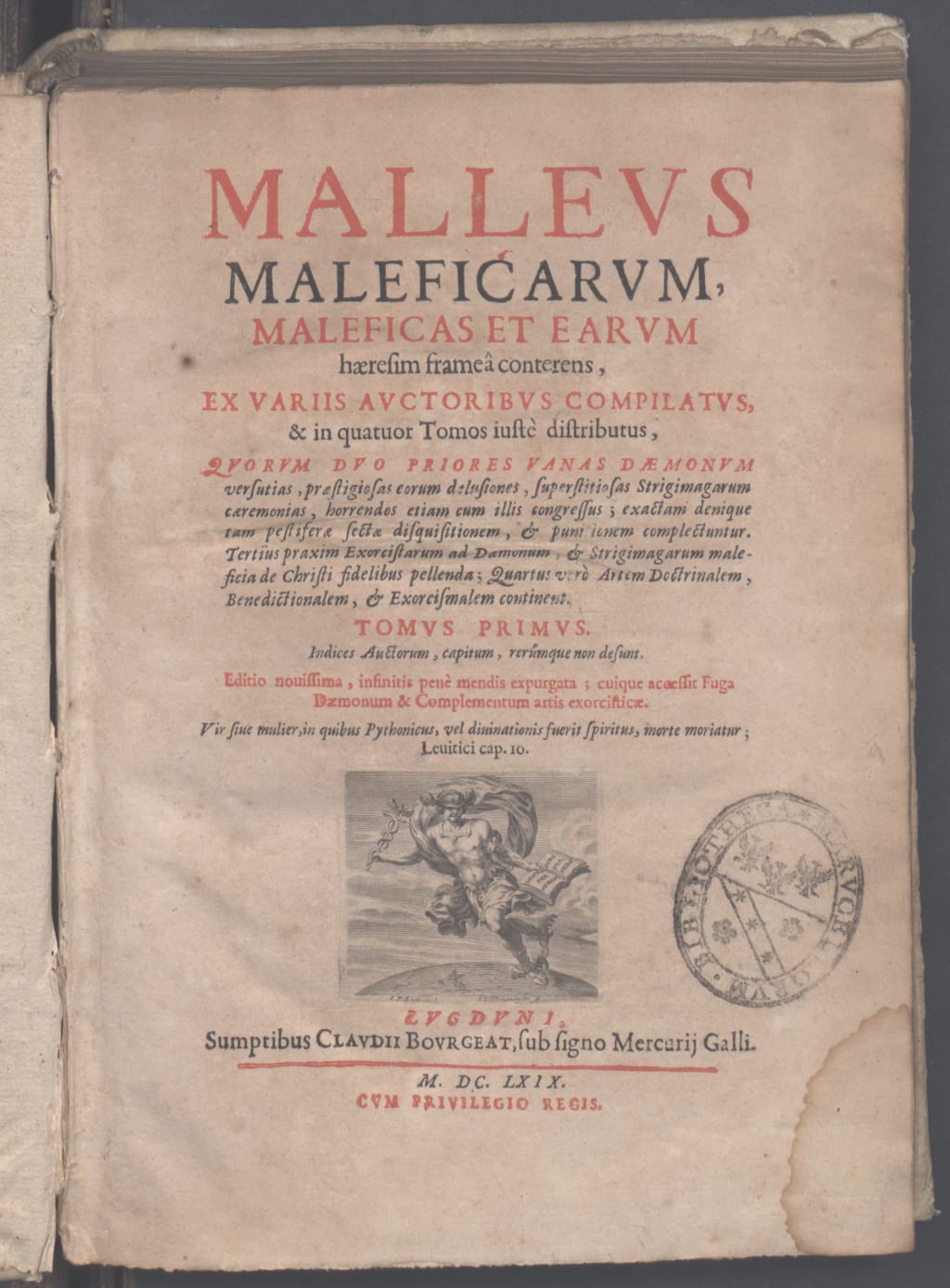

The Malleus Maleficarum, or The Hammer of the Witches, is one of the most notorious books published.

While it isn't the only witch hunting manual that was released during the witch craze, which lasted from the 1400s to the 1700s, it is the most well known. It is also the book that gets the most blame for the deaths of thousands of innocents.

For those who are new to witchcraft and its history, there are many questions surrounding the text. Which makes sense. Even historians still have questions about it.

One of the biggest, though, surrounds the papal bull included in the book, Summis desiderantes affectibus. This bull was issued by Pope Innocent VIII on December 5, 1484 to one of the authors of the book, Heinrich Kraemer (also known by his Latinized name Henricus Institor).

The debate about this bull consists of two sides: Those who believe Innocent VIII gave Institor permission to use it in the Malleus Maleficarum and those who believe Institor used it without permission.

To understand these two conflicting possibilities we need to look at how the book came to be.

Institor was born in 1430 in Schlettstàdt, and he joined the Dominican Order at a young age.

During this period, there were several groups the Church was working against. Many people were becoming disillusioned with the Church and had splintered into different groups that worshipped in their own way.

This was precisely why the Inquisition had been created and they were kept busy as Pope Innocent VIII demanded the end of the Waldesians and the Hussites.

By 1467, Institor was battling Hussites in the Holy Roman Empire. At the time, there was a burgeoning belief that not only were their devil worshippers among the Hussites but that there were also witches.

Once Institor moved on from the Hussites, and down into Germany, he still continued his pursuit of witches. However, belief in witches was considered heresy, as the Church did not recognize them.

This meant Institor didn't get the support his role of Inquisitor would normally command. Since the belief in witchcraft was heresy, few would help him or allow him to try supposed witches.

Thus Institor made an appeal to the pope about his predicament. Innocent, who was aware of the widespread belief of witches, issued the infamous papal bull that officially acknowledged witchcraft and the threat it represented to the Church.

The bull gave Institor more confidence in his pursuit to end witchcraft. However, his reputation preceded him. He was known for being cruel, overly zealous, and for his fixation on women.

When he and fellow Inquisitor Jakob Sprenger arrived in a small town called Innsbruck to bring justice, many already knew who he was. At one point, while walking down the street, he came across Helena Scheuberin, who recognized him.

Allegedly, she turned and spat at Institor saying, "Fie on you, you bad monk, may the falling evil take you." By doing this she painted a bullseye on her back.

Unfortunately for Scheuberin, she was known in her community as a woman who had no problem sharing her opinions. In fact, she'd been avoiding Institor's sermons for the most part and called his views heretical at one of the few she had attended. It also didn't help that she was believed to be promiscuous and was rumored to be responsible for many family troubles in the community.

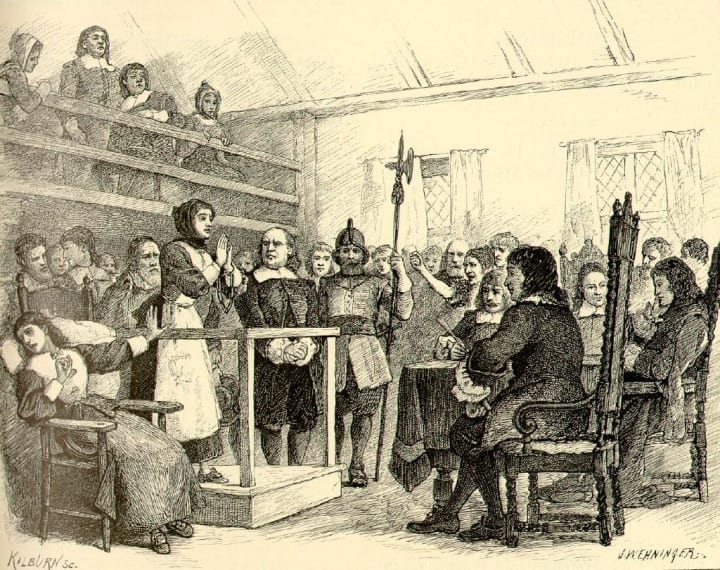

It wasn't long until Institor had Scheuberin arrested and tried for witchcraft. During this trial, six other women were accused, and initially, Bishop Golser supported Institor in his efforts.

However, when Institor began questioning Scheuberin, he focused more on her sexual acts than anything else. His queries were explicit, specific, and aggressive. Many in attendance felt uncomfortable with his efforts, and Golser called for a break and advised Institor to change his line of questioning.

When the trial reconvened, Scheuberin had a lawyer. Again, when Institor began his examination, he was aggressive. The lawyer did his job, interjecting when necessary and pointing out the flaws in Institor's theories.

Eventually, Golser had enough and ended the trial. All of the women were dismissed, and if any of them received punishment, it was mild.

This treatment infuriated Institor. He left Innsbruck, after Golser asked him to leave, and retreated to the Universite of Cologne to write the Malleus Malleficarum with his colleague Sprenger.

Due to the invention of the Guttenberg Press in the 1430s, mass producing books wasn't difficult. But though the press made creating the book easier, it also added an additional step for Institor.

Some Bishops took issue with the mass production of the Bible, as errors could be compounded in many books. Producing dangerous, heretical material was also easier. They wanted the Church to have tighter control over printed material. Thus, it was encouraged, though not required, for books to be preapproved for printing.

To give the book credibility, Institor published the Approbation of The Following Treatise and The Signatures Thereunto of The Doctors of The Illustrious University of Cologne as well as Innocent's papal bull. By doing this, Institor was able to give his work the support of the Church.

And this is where the crux of the matter lies. A common myth is that Pope Innocent VIII commissioned the Malleus Maleficarum. But he most likely didn't. In fact, scholars argue that he was unaware that Institor was including the bull in his book.

Some believe the Approbation had also been falsified. Or at the very least, those who signed it had failed to completely read through the tome.

Some historians say that Innocent had the book banned, and even the members of the Inquisition didn't use the book for hunting witches. The guidelines for what Inquisitors were allowed to do to bring about a confession were vastly different than what was laid out in the Maleficarum.

The most notable difference was the confirmation of the confession. For the Inquisition, any confession brought about through torture had to be reaffirmed the next day. They were after the truth; the torture wasn't about punishment.

So, if the person confessed again the next day, their punishments were lessened. Some were sent on pilgrimages or other acts of penance. Generally, those who recanted their confessions would be imprisoned or given to secular authorities to be burned at the stake.

However, they were instructed to only torture the accused once, and in that, they could not kill or maim the accused. This rule wasn't always followed, but that was the guidelines they were given.

In the Maleficarum, Institor created a loophole for torture. Rather than considering the following torture as a second bout, one could say it was a continuation of the previous torture.

In fact, Institor wasn't really interested in finding the truth, but rather in punishing women. Nearly all of his recommended practices resulted in death, such as tying rocks to a suspected witch and throwing her in a lake - if she floated she was a witch, if not, she was innocent.

So, when the Inquisition was presented with Institor's work, they turned their back on it. It didn't uphold the Christian values of correction rather than punishment.

In short, it's unlikely the Church commissioned the book or even meant to lend it support. That being said, the events that took place 600 years ago are not easy to confirm. And it's important to remember that the victors write the histories.

Sources

“About: Helena Scheuberin.” Dbpedia.org, dbpedia.org/page/Helena_Scheuberin. Accessed 10 Feb. 2023.

Briggs, Viktorija. Historical Names & Dates in Paganism / Witchcraft. 11 July 2012. Scribd, www.scribd.com/document/99756363/Historical-Names-Dates-in-Paganism-Witchcraft#. Accessed 7 Feb. 2023.

“CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Witchcraft.” Www.newadvent.org, 1995, www.newadvent.org/cathen/15674a.htm. Transcription of Catholic Encyclopedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church originally published in 1913. Kevin Knight digitized the book starting in 1995 with other volunteers. The final transcription was completed in 1997.

Deyrmenjian, Maral. Pope Innocent VIII (1484-1492) and the Summis Desiderantes Affectibus. PDXScholar, 2020, pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mmft_malleus/1/?utm_source=pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu%2Fmmft_malleus%2F1&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages. Accessed 31 Jan. 2023.

ESOTERICA. “Witchcraft - Malleus Maleficarum - the Hammer of Witches - History and Analysis of the Inquisition.” YouTube, 8 Oct. 2021, www.youtube.com/watch?v=uIdcjeeYjaE.

Freeman, Shanna. “How the Spanish Inquisition Worked.” HowStuffWorks, 5 Feb. 2008, history.howstuffworks.com/historical-figures/spanish-inquisition3.htm#:~:text=Torture%20was%20used%20only%20to. Accessed 7 Feb. 2023.

Hume, Samuel. “Episode 1 – the Hammer of the Witches.” Pax Britannica, 7 Oct. 2018, thehistoryofwitchcraft.co.uk//episode-list/episode-1-the-hammer-of-the-witches/. Accessed 10 Feb. 2023.

“Innocent VIII | Pope | Britannica.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 2020, www.britannica.com/biography/Innocent-VIII.

Jorge, AMCM. “The Lusitanian Episcopate in the 4th Century: Priscilian of Avila and the Tensions between Bishops.” Www.brown.edu, 2006, www.brown.edu/Departments/Portuguese_Brazilian_Studies/ejph/html/issue8/html/ajorge_main.html. Accessed 7 Feb. 2023.

Midelfort, H. C. Erik. “Recent Witch Hunting Research, or Where Do We Go from Here?” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, vol. 62, no. 3, 1968, pp. 373–420, www.jstor.org/stable/24301678?seq=7#metadata_info_tab_contents. Accessed 6 Feb. 2023.

Minnich, Nelson H. “The Fifth Lateran Council and Preventive Censorship of Printed Books.” Annali Della Scuola Normale Superiore Di Pisa. Classe Di Lettere E Filosofia, vol. 2, no. 1, 2010, pp. 67–104, www.jstor.org/stable/24308618. Accessed 10 Feb. 2023.

Roos, Dave. “7 Ways the Printing Press Changed the World.” HISTORY, 28 Aug. 2019, www.history.com/news/printing-press-renaissance#:~:text=German%20goldsmith%20Johannes%20Gutenberg%20is.

About the Creator

Amanda Jeffery

Amanda is a creative writer, journalist and witch. She has been writing since she was knee high to a grasshopper, and is a freelance writer. She has published a fantasy novelette, The Fourth Year Spell, which can be found on Amazon.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.