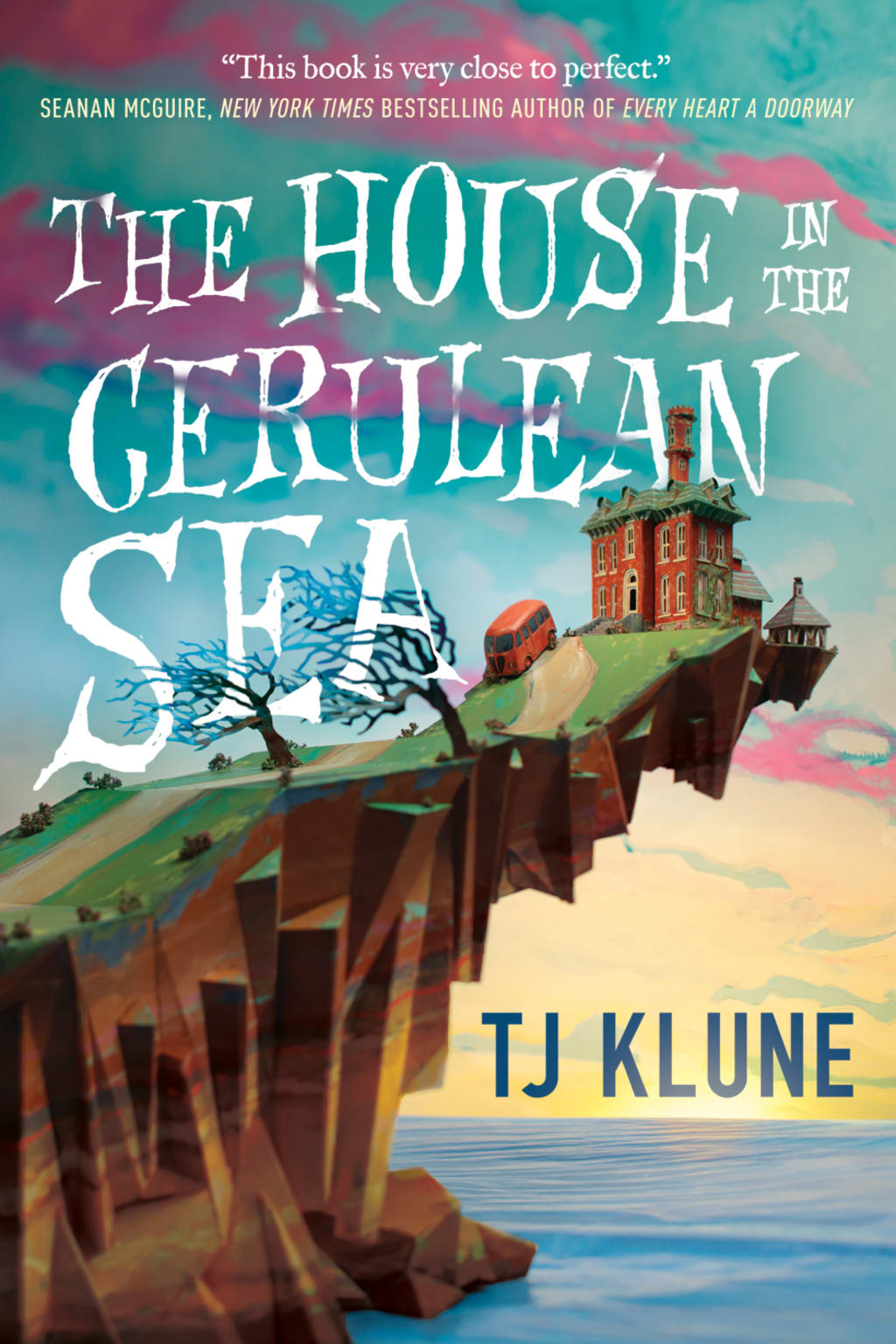

Book Review: The House in the Cerulean Sea

A magical tale of found family

The House in the Cerulean Sea, written by T.J. Klune, is a contemporary fantasy/LGBTQ+ romance that poses two very simple questions: what do we gain by taking a chance on other people, and why are we so often reluctant to take a chance on ourselves?

I picked up this book because I love stories about found families (particularly of the magical variety), and because I needed something whimsical in my life after the hell-storm that has been this year. The House in the Cerulean Sea delivered more than I could have asked for. It was saturated with so much love, humor, and hope that—by the end—I cried tears of genuine happiness. I can’t remember the last time a book made me do that.

I think if a book sparks that much joy, I have an obligation to share it with as many people as possible.

Let's talk about the plot

The protagonist of this story is one Linus Baker, a middle-aged caseworker at the Department in Charge of Magical Youth (DICOMY) who lives in a perpetually dreary city with a moody cat and a collection of old records. When Linus is sent on a classified assignment by Extremely Upper Management, he is convinced it will prove to be the challenge of his career—or the end of his days. His task is simple: travel to the Marsyas Island Orphanage, a place where the weather is temperate and the sun always shines, and observe the occupants for a month before making a recommendation on whether the orphanage should remain open. However, it soon becomes clear that there is more to life on Marsyas than can be contained in his files.

Occupying the island are the charming and mysterious headmaster Arthur Parnassus, the island’s spite caretaker Zoe Chappelwhite, and the six motely, magical youths under their care. They are:

- Talia, a 263-year-old gnome (which I assure you is still very much a child in gnomish years) who takes pride in her roundness and sprawling garden.

- Theodore, a tiny wyvern who keeps a hoard of treasures under the couch, and whose wings are so disproportionately large that he can barely walk without tripping over them (which is about as adorable as a puppy tripping over its ears).

- Sal, an incredibly shy were-Pomeranian who transforms when startled.

- Phee, a powerful sprite under Zoe’s tutelage.

- Chauncy, who is…a bit of a mystery. Nobody really knows what he is, but he looks like a green blob with antenna for eyes.

- And Lucy (short for Lucifer), the antichrist himself.

Despite their differences, there are two fundamental qualities each of these children have in common: each has struggled against preconceptions of what the world thinks they should be, and each is fiercely protective of their island family. The orphanage is the only place they have in the world to truly be themselves. And Arthur Parnassus would do anything to keep it that way.

As Linus uncovers secrets that test his impartiality, and as he grows closer with the children and their caretaker both, he is forced to reconsider everything he thought he knew. And as pressure mounts to return to DICOMY and complete his report, he must confront the one question that threatens to change everything:

Don’t you wish you were here?

As the scale of this description might suggest, The House in the Cerulean Sea is very much a character-driven novel. The plot itself is rather simple, and the drama played out on an intimate scale. To be clear: I don’t consider a simple plot to be detrimental to a book. On the contrary, I think it makes it all the more difficult for an author to hold their reader’s attention.

Our main source of conflict is an allegorical prejudice against magical creatures, which Linus must confront both within himself and the nearby village. In this sense, A House in the Cerulean Sea is very much a book for the times. There are clear lines of inspiration drawn between the events in the book and the real world. When concerned citizens complain about the proximity of the orphanage, or tout their religion as grounds to threaten a child they’ve never even met, we recognize that their counterpart exists in the real world. When we see how the town is plastered with tongue-in-cheek signs reading “If you see something, say something,” we know first-hand how reinforcements such as this can create an atmosphere of suspicion and distrust.

In another story (or another voice), it could be pretty dispiriting stuff. However, Klune’s story chooses to focus on the power of acceptance. In even those particularly unsympathetic characters who serve as antagonists, there is still hope that they are redeemable. If there weren’t, the entire point of the story—that people can learn to look beyond their narrow worldview with enough love and understanding—would be completely negated.

Take our main character, for example. When I was first introduced to Linus, I honestly wasn’t sure if I was going to like him. He had been thoroughly convinced that the children of Marsyas were dangerous solely because of what they were rather than who. If he hadn’t been willing to reconsider, then we readers would have been left with no story at all.

Plot aside, I consider Klune’s ability to manipulate character one of the greatest strengths of this novel. I envy his ability to juggle such a unique and distinct cast with such apparent ease. Each of his carefully-placed beats adds depth and encourages growth.

At the beginning of this novel, I considered Linus a cocktail of nerves and long-suffering ennui that was just about as colorless as his office. The attention Klune gives to his only personal effect in said office—a mouse pad of a scenic beachfront that asks the eternal question: Don’t you wish you were here?—stank of a particular brand of literary malaise that I typically tend to avoid. Now, I consider him just about as dear as the children themselves. He proves to be both the type of person who sleeps with a copy of DICOMY’s RULES & REGULATIONS on his bedside table, AND the type of person who is so singularly dedicated to protecting children that he will endure anything if it means he can make a difference—including DICOMY. He proves to be more than meets the eye.

So what about the romance?

The House in the Cerulean Sea is an achingly tender slow burn. Our two love interests, Linus and Arthur, bumble around each other in a classic case of will they/won’t they. Their scenes together are funny, sweet, and brimming with affection—the cherry on top of an already wonderful book. They have the kind of chemistry that is so obvious that even the other characters feel compelled to root for them.

Within the context of the broader story, what I like most about Linus and Arthur’s romance is how it reinforces this idea of taking a chance on ourselves and each other. Both have plenty of reasons to write off their feelings as inappropriate or inopportune. Linus in particular knows that it would be far easier to return to the life he led before, which if not particularly exciting was at least uncomplicated. Neither expects to fall so quickly or so thoroughly.

But love finds us in the most unexpected of places. Sometimes, that place is an orphanage at the end of your known world. And the question Klune poses through this relationship is one that everyone has to answer at some point in their lives: do I follow the easier path, sacrificing nothing, or do I risk it all in the hopes that I will be happier in the end?

Because love isn’t something that is simply going to fall in to your lap. It is something you have to choose.

Criticism

I think it’s pretty clear by now that I absolutely adored this book. It almost pains me to imply that it wasn’t perfect. However, for the sake of a fair review, I feel it is only right to acknowledge that there always elements in any book that could be stronger.

If I had one criticism to share on Klune’s craft, it would be the somewhat heavy-handed dialogue. Most of the time, conversations felt natural and normal. There were points, however—typically during confrontations with the townspeople—where I felt characters were allowed an unrealistic amount of space to speak their minds.

While it is certainly satisfying to see a bunch of bigoted townspeople told off, it also felt a bit like the author was holding up his hand, telling the reader that it was called “the point,” and then smacking them across the face with it. Not particularly subtle. Probably could have been a bit more earned.

That being said, if the exchange for these monologues is the hope that people can actually change, then this is one allowance I will gladly make. I’m not too jaded (yet) to believe it couldn’t actually happen.

And let’s be honest: the idea of sharing these thoughts uninterrupted—to be heard in an age when people so often have already made up their minds—was such a nice bit of escapism that I hardly even minded.

Final rating

I give The House in the Cerulean Sea 4.5/5 stars. It was one of the best books I have read in a long time. It was one of the most hopeful books I have read in a long time. And certainly the sweetest.

Do yourself a favor and go read it.

About the Creator

Melissa Close

I'm a graduate of Emerson College currently working in academic publishing. I write for my own enjoyment on a variety of topics that interest me (fantasy, pop-culture, current events, etc). I hope you enjoy reading!

Twitter: @MelissaClose20

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.