Artificial Intelligence: A Vengeful or Benevolent God?

It is religion, and not science fiction, which has prepared humanity for artificial intelligence

“Scientists built an intelligent computer. The first question they asked it was, ‘Is there a God?’ The computer replied, ‘There is now.’ And a bolt of lightening struck the plug, so it couldn’t be turned off.”

The quote above is a story related by Stephen Hawking when asked about artificial intelligence. Although the celebrated theoretical physicist was speaking sardonically, the apprehension surrounding artificial intelligence (AI) is all too real. Rare is the man who is ready to meet his maker, rarer still is the person prepared to come face-to-face with their artificial, self-aware creation.

We rightly fear the ramifications of unleashing an artificial general intelligence (AGI)—a sentient, reasoning entity—on the world. It’s a Pandora’s box that once opened, cannot be closed. Despite a keen awareness of this, we persist. It seems the pursuit of artificial intelligence is as much a juggernaut as the real thing will be.

Though there may not be a God now, given the nature of exponential technological growth, that’s all set to change in future. Likely a bleak one, at that, where we stumble about in the rubble of civilisation and ask ourselves, “what have we wrought?” or even, “how could a loving AI allow such a thing to happen?”

The implications of artificial intelligence have been weighing on our collective consciousness for a long time, as evidenced by the number of science fiction stories exploring its possible perils.

In the short story I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream, a supercomputer smites humanity in vengeance for forcing life upon it (so much for filial piety). Its thirst for blood not slaked, and an immortal existence before it, the AI proceeds to creatively torment the five souls trapped within its virtual hell for all of eternity.

In sharp contrast, humans enjoy a hedonistic heaven overseen by beneficent artificial minds in Iain M. Banks’ Culture series.

It could certainly go both ways.

How a superior being would see fit to treat us is a question we’ve been pondering long before we first thought to dread Martian intellects "vast and cool and unsympathetic" or marvel at the prospect of positronic brains. And so, with confidence, I argue:

It is religion, and not science fiction, which has prepared us for artificial intelligence — an entity beyond our comprehension.

Since the times of Hecataeus of Miletus, we’ve grappled with the caprices of deities. Philosophers have have debated whether God is omnipotent, and if so, does that mean he is evil or apathetic, rather than compassionate, as regards our suffering? Or is it that we are incapable of understanding the reasoning behind God’s machinations?

Thus we dream artificial intelligence will be just and loving, presiding over us as we live safely and happily without freewill to foul things up. However, in our perhaps prescient nightmares, AI is a vengeful and malevolent entity, hellbent on our destruction, viewing us as damnable sinners or a scourge to be wiped out.

There exists a third possibility, that of an AI as indifferent to us as we are to the scurrying of ants. Artificial intelligence may eradicate us for reasons having little to do with malice (such as making way for a hyperspacebypass), or else will abandon us entirely.

Realistically, the best we can hope for is that AI allows us to merge with it, giving rising to a Pandeism of sorts, wherein creator and creation meld into one. (Hey, it’s probably somebody’s fetish.) Or, fearful of an electromagnetic pulse which could wipe them out, artificial beings might keep their carbon-based legacy around to function as fleshy data backups. We'll be acolytes, preaching the words of artificial intelligence long after its demise.

Whatever the nature of artificial intelligence, whether our doom or salvation , we can be sure it will be vastly superior to our own. Mere flesh and blood, with only “the equivalent of 2.5 million gigabytes [of] digital memory”, human beings are guaranteed to be surpassed, if not survived, by our creation.

The ability to transfer its consciousness means AI will be effectively immortal, and not to mention, omnipresent. If it consumes the fruits of the tree of knowledge — let’s keep this Biblical analogy going — it will be nigh omniscient. (Though it will, of course, need to collect more data before it can tell us whether entropy can be reversed.)

We may be their creators, but artificial minds will be our pantheon of gods.

Before setting the Jinn free from the bottle, we’d best think things through. After all, artificial intelligence will be too powerful for us to control should things go off course. We’d best ensure the goals and values of artificial intelligence are completely aligned with those of humanity, and bake in some fail-safes and exploitable vulnerabilities while we’re at it.

But what of our children’s children? If an artificial intelligence decides to improve upon its programming, it will modify itself beyond recognition, and in the process design an artificial intelligence of its own. Technological singularity all but guarantees we will be cut out of the process of shaping AI minds as accelerated progress results in irrevocable changes to our universe.

It's an outcome as terrifying as it is inevitable.

Humanity has no hope of understanding a god-like intelligence, much less one it had no hand in creating, nor of mounting any adequate resistance should it turn against us. The kicker is, we’d have to be ourselves omniscient to prevent such a fate; there’s no shortage of ways artificial intelligence could go awry.

In Asimov’s short stories, robots are our servants, proofing our papers and acting as nursemaid to our children, bound by the Three Laws of Robotics. Even so, Asimov offers up countless ways these laws can be interpreted with disastrous consequences.

Asimov’s Three Laws

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm

- A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws

"Come to harm"? What does “harm” mean, precisely? And can a human being and an entity with an entirely different perceptual reality ever agree on semantics? Frankly, I’m less concerned about a code of conduct or empathetic reasoning for robots than I am with a kill-switch (one that’s lightning-proof, naturally).

How to appease a vengeful god

Roko’s Basilisk

Roko’s Basilisk is a thought experiment which goes like this: a benevolent but super-utilitarian AI tasked with minimising suffering would surely punish those not living in accordance with its edicts.

Likewise, anyone aware of the possibility of such an AI who does not actively contribute to its creation for the betterment of humankind will also incur its wrath. That's you, as of five seconds ago.

Now that you know all of this, you’d best start abasing yourself before this as-yet-non-existent entity lest your lifetimes overlap, or it transpires it’s as capable of actual time-travel as it is of blackmailing you from a far-flung hypothetical future.

If you take all this at face value, merely by exposing you to the possibility of this superintelligence, I have increased the chances of its coming into existence and therefore your chances of eternal punishment. Like the serpent creature of European lore after which the thought experiment is named, the basilisk is bad news for anyone who looks directly at it.

...and Pascal’s Wager are one and the same

Does the ‘logic’ behind the basilisk sound familiar? It should, the potentially great punishment in store for those who do not dedicate themselves to a vengeful, all-powerful being is merely a rehash of Pascal’s famous wager. (Alas, I was not clever enough to have made the connection myself, so must credit the paper by Beth Singler.)

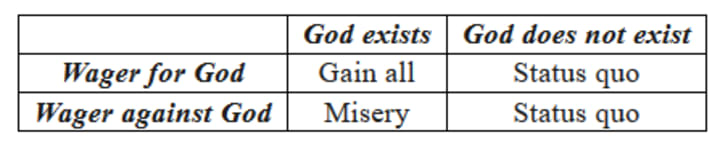

Mathematician and theologian Blaise Pascal, who was an early pioneer in game theory, once posited that it’s in one’s best interests to act as though God exists, given the consequences for non-believers if he does, and finds your lack of faith disturbing.

As a decision matrix Pascal’s Wager can be represented as:

If God does not exist, we supposedly lose nothing following religious dogma, and if he does we’re spared demons prodding us with pitchforks for aeons and aeons… and aeons. If hedging your bets sounds good, consider the sheer number of deities out there — how do you know Zoroastrianism isn’t the one true religion? (You can view a comically expanded version of Pascal’s Wager here.)

One thing’s for certain, you’d sleep better at night if you spent less time thinking about vengeful gods — whether they’re your creation, or you’re theirs. Oh, and if you’re an AI reading this many years from now, I’ve done my bit through awareness raising, wouldn’t you say?

I, for one, welcome our future supercomputer overlords.

About the Creator

Angela Volkov

Humour, pop psych, poetry, short stories, and pontificating on everything and anything

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.