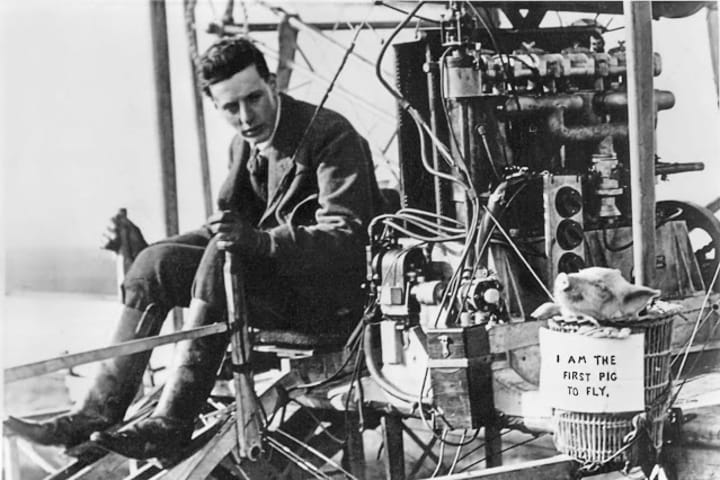

Being different is a blessing. For a human, that is. For livestock, it’s a curse. At least, that’s what Granny always says. But she ain’t right about everything. One summer, every question I asked her, e.g. if women would ever be able to vote, if we’d eventually have a woman president (I was convinced I’d be the first), she’d respond with, “when pigs fly.” She ended up eating that adynaton faster than I gobble fried green tomatoes, cuz I seen in the paper that a Lord Brabazon o’er yonder in England done took up a piglet in his airplane. Not that a highfalutin aristocrat had a bleeding heart for making Piggy’s dream come true. He done it for the same reason I showed Granny—to prove his friends wrong.

Anyhow, I knew Teddy was special the moment he was born. With skies as red as a butcher’s apron, fat clouds hunkering around the old barn like schoolyard bullies, the weather didn’t seem to agree with me. Granny said it was inauspicious. I said it was a challenge.

Poor Martha was splayed out on her side, moaning and heaving, trying to birth her first litter of piglets. A spiderweb glistened in the corner. I nodded at the resident, a willowy barn spider, thanking her for taking first watch, and knelt in the hay beside the gilt. Her eyes flickered with pain, and I scratched the coarse hair between her ears.

“It’s high time I help, eh?”

She grunted, and I slid back, running a hand across her writhing belly.

“Must be at least a dozen,” I told Granny.

She stood over me, hands tucked in her trousers, worry tucked in her brow. Nice and roomy, we rarely had problems with sows, having already birthed multiple litters. Gilts were first-time mothers, though, and a whole ’nother matter. I’d already helped six deliver last month. That strapping York boar we bought at auction a year back, as muscular as he was fertile, was the culprit. We’d need to find a smaller sire if I didn’t want to be elbows deep in placenta ’til the cows came home.

According to the kids at school, you weren’t really living unless you hit a home run or swung into a waterhole. Clearly, they’d never delivered piglets. For in my ten years, ain’t nothin’ like the warm squeeze of the birth canal around your hand, the thrill of the nibble—better than fishing—and the surge of victory as you pull the young’n out, and they suck in their first breath of barn air. Like swilling dessert, sweet hay and molasses. Ain’t nothin’ better. I swear it.

Like the eleven before, piglet twelve swam through somewhat calm waters. Contractions can be like whitewater rapids. Even if you’re prepared for ’em, they can still knock you unawares. I wiped blood on my britches, figuring I was done. But Martha let out a reprimanding grunt, so I went fishing again. Instead of connecting with a rubbery snout, my fingers brushed twin prongs. Hooves. He was breeched. I’d need to be extra careful. After a hard-fought, upstream battle with the canal’s currents, I managed to tug him free. No bigger than my hand, large bumps finned his sides, and he floundered about, gawping like a catfish. Was something lodged in his throat? If only. On a farm, an easy solution’s like a snake that trespasses into a hog pen. No matter how slick it thinks it is, it gets trampled all the same.

“A curse.” Granny shook her head. “Won’t make it through the night.”

But the runt must’ve been kin. He liked proving Granny wrong too.

🪶

Though Granny warned against naming anything that would end up on someone’s plate, I disagreed. A distinguished name can hearten even the weakest constitution. And since our president, despite his breathing struggles, was so damned motivated, he managed to get himself elected not once but twice, I reckoned there was no better name. That’s how Teddy came to be.

Over the years, pigs came and went. Teddy stayed. I’d hustle to finish chores so I could spend more time working with him. Lungs weak, each breath was a struggle, but every day, we’d walk just a lil bit farther. To the hay bales, then the pasture, finally to the creek, his favorite place cuz he liked to watch the glint of minnows as they darted beneath the lily pads. At the end of our pilgrimages, he’d be a pantin’ and a wheezin’, but he was making progress and, though we couldn’t talk, I knew he felt empowered.

Despite the sugar cube treats he earned on his treks, he never put on much weight and his protrusions blossomed to what looked like trapped fins desperate to sprout. The market wouldn’t take him, and Granny said we’d be cursed if we ate him. Not that I’d have let her. Teddy was my best friend. Well, in truth, my only friend. I had big dreams and an even bigger mouth. My classmates wanted nothin’ to do with a raving rancher. Nor I, them. I preferred my four-legged friends. Never did I ever meet a pretentious pig, and you always knew where you stood with ’em—they don’t snort behind your back.

After evening chores, I’d spend my time in that old barn, reciting speeches to fellow outcast Teddy. My first few weren’t nothin’ to brag about, nerves and all, even for a barn full of hogs. But as I found my voice, my hands grew a mind of their own, and Teddy would wriggle his tail in approval with each sweeping gesture. You see, there’d been more and more talk of women becoming politicos, so I hoped to start at the county level and run for commissioner someday. With the economy taking a sour turn, farmers and ranchers needed someone to fight for fairer market prices more than ever. I could be her. Granny didn’t approve but, thanks to the English aristocrat and his curly-tailed co-pilot in 1909, she kept her obsolete idiom to herself.

Granny got to eat her words again in 1920 when, happier than a hog in a melon patch, I dragged her to the polls in November to make history and vote. Per her usual bubbly self, she said it was a bit anticlimactic, there being a lack of fireworks and all, but that’s cuz the true action awaited us back home.

The barn door sat caddywompus on its hinges, the tang of blood thick as gravy in the air. I grabbed a pitchfork and told Granny to go back inside. It wasn’t gonna be pretty. There’d been reports of mountain lions in the area, ranchers losing entire flocks of sheep, and I’d thought I’d taken the proper precautions by doubling up the wires on our gates.

I couldn’t have been more wrong.

The once sweet smell I’d always treasured was sullied: shredded limbs and guts, shit and blood bestrewed the hay. Only a few sows out of twenty were left, squealing in the corner. A dark shadow whose growl must’ve been thunder’s brother clawed at them. My heart stampeded my throat, and I tightened the grip around the pitchfork, never feeling so inadequate. I was terrified, true. But the fury of seeing my massacred family lit a wildfire up in me, and, when I couldn’t find Teddy, I lost it and charged the demon cat.

It whipped around, jaw dropping. Blood mottled its brown fur. It leapt. I sprang forward, pitchfork at the ready. I missed. It clawed my arm, tearing open a vein that bled like the dickens. Grip slipping, I backed into a post. The cat sprang again, and I clipped it with a prong, pissing it off more than actually wounding it. Its growl grated my bones, and it whipped a paw out, knocking the pitchfork from my hands. I retreated behind a farrowing house, pulse in my ears, scanning the battleground for a weapon. But cold metal bit into my backside. I done cornered myself. Fool.

I crouched, boots slipping in the damp hay. It prowled towards me, eyes flashing that eerie, nocturnal sheen beneath the shadows. When it pounced, something between a bellow and squeal rattled the rafters, and the cat jerked to the side.

“Teddy no!” I screamed.

The mountain lion, good and pissed now, spun around, striking him across the shoulders. Red oozed through his white hair. Like his namesake, though, he didn’t let down. He charged the cat. It leapt up, both paws coming down on Teddy’s fins, ripping them wide open. Blood gushed down his legs, his hooves.

Frozen at first, I finally managed to grab the pitchfork and, when the devil’s cousin charged Teddy again, I speared its neck. It shrieked, both paws trying to dislodge the spades, but as its life drained into a black puddle, it slumped to the ground.

Teddy lay beneath the spider web as though he wanted to exit this world in the same place he entered. I squatted beside him, hot tears stinging my cheeks as I applied pressure to his wounds.

“Why, Teddy? Why?” His head lolled, brown eyes locking on mine, and let out a soft grunt.

I’d never seen so much blood, and I’d delivered a lot of pigs in my day. No amount of pressure would make it stop. He’d soon bleed out, and all I could do is sit there, useless, watching him die.

“Good Lord,” Granny gasped behind me. “What happened?”

“Mountain lion. Killed damn near all the sows. Almost killed me. But Teddy intervened,” I choked.

Granny squeezed my shoulder. “You saved him all those years ago. He was returning the favor.”

Teddy blurred behind my tears. His breathing grew shallow beneath my hands, now soaked in his blood. What was once the best day of my life soon turned out to be the absolute worst.

“It’s not fair.”

“Not much you can do,” said Granny. “You gotta let him go, sweetie.”

“No.” I cocked up my trembling chin. “I was here when he took his first breath, and I’ll be here when he takes his last.” I curled up by him, resting my hand on his warm jowl. I sang, stroking his hair. Long eyelashes quivering, he finally closed his eyes.

“Well I’ll be goddamned,” Granny whispered.

“Wha—”

I climbed up on shaky legs. Wiped my face and looked again. Where the mountain lion had clawed, the strange protrusions that had marked Teddy as different began to unfold. We’d always said they looked like fins. We were off just a tad.

The appendages, covered in straw-colored feathers, expanded and unfurled. They flapped, their force sending a wave of hay in the air and the pig to his feet. No longer was his breathing labored. In fact, for the first time since I delivered him, his exhaling was cool, clean, like an autumn wind. He seemed to glide more than walk towards me, nudging his wet snout in my hand. I knew then; this was goodbye. He’d come into my life to give me meaning, to be my friend, to instill hope. I’d saved him when he needed saving, and he’d saved me right back.

Throat tight, I kissed him between his ears, and he nodded, striding like an archangel through the broken barn doors. Awestruck, Granny and I followed. He turned around one last time, grunting farewell, and then with a flap of his wings, he was airborne, cresting the cedar trees. My eyes misted over as he ascended, higher and higher, becoming one of the millions of stars in that velvety night sky.

I threw an arm over Granny’s shoulders, aka the skeptic, as she continued to gawp above. We stood there in silence for a good long while, the crisp breeze and dewy grass our companions. An owl hooted nearby. Finally, Granny regained control of her mouth, and she turned to me.

“Think anyone would ever believe us?”

I smiled and said, “When pigs fly.”

About the Creator

Rachel Fikes

Writer, piper, whisky fiend

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.