I wake to the sound of seagulls. Though the nearest coast is twelve miles away, I’m told, the birds flock and caw each morning outside our windows. I sit up, stretch my arms over my head, and let out a sound to match. The alarm rings and I try to remember the last time I relied on it to wake me.

Feeling for the window sill, I stick my head out—just enough to catch a breeze. I can hear my older sister Lilia saying her morning worries from the window next door. Wasting no time, I hurry to the bathroom, Lilia yelling after me as I lock the door behind.

A splash of cold water to my face. Then three eyedrops—one, two, three—twice for each eye, straight down the drain. I can just make out a fuzzy imprint above the sink, the discolored square where a mirror once hung. Once I’m out, I grab the diary from under my bed and take the stairs two at a time.

It’s enriched yogurt for breakfast, like always. Mother speaks gravely of a time before doctors understood the importance of the microbiome—when people thought sleep and diet and exercise were all that mattered. Before everything was infused with lactobacillus and cordyceps, packed with probiotics and fungal supplements. When people were still allowed to spend a day at the ocean, I think, trying to imagine the vast, roiling waves. I’d heard it once—in a dream. That deep eternal rumbling, like the earth when it shakes, but ebbing, flowing, with timeless reason. How would it feel, to be taken up by it? Different from the shower head that sputters filtered rainwater from the roof collector. Or the milky pond where we dipped our feet each month on the full moon, my favorite of the remaining rituals. Now we bathe our feet in the icy stream, but it’s not the same.

They said father came from the coast. That he’d been born at a time when thousands of people worked to construct seawalls sturdy enough to afford the rich their ocean views—built where none should live—and those without the money for walls had their homes washed away one too many times so that they fled inland, or disappeared. Father had made it to VIISTA somehow. But then he’d grown tired of a life landlocked and dry. Lilia used to whisper stories to me at night. Father had been called back to the ocean, she told me, and he would send for us one day.

I knew even then that part wasn’t true. I’d wanted to remind her that she could get in serious trouble for spreading untruths, but held my tongue and dreamed instead.

Don’t forget to be home by six for Ceremony, mother calls out as I gather my books and the diary into my backpack, grab my jacket, and make my way for the door. When she thinks I’m being stubborn she calls me Your-father’s-daughter. I’ve heard aunts say that mother was a beauty—still likely is, though of course I’ve never seen her face—and though mother sucks her teeth and protests, it’s the only time I’ve ever detected a hint of it in her voice, a yearning for the time before.

I’ll be here. Promise.

Only promise—

What you can keep, I say, I know. I kiss her soft cheek on my way out and smell lavender, feeling sorry that there will come a day, not too long from now, when I won’t be able to promise anymore. Best to be good to my word until then.

Father had lived for years in VIISTA, but then one day, almost fifteen years ago now, just as vision concession was becoming mandatory, he left. He was called the People’s Governor, helping anyone however he could, but nobody mentions his name now because they see what he did as betrayal. I think he’s brave.

The elders only spoke of the time before when we were celebrating something—a birthday, a marriage, another year of no new infections—as if relief allowed the mental trip back in time. You could hear they enjoyed remembering. Before the latest mutation, before communities like VIISTA were partitioned, temporarily at first, to control the spread. Then permanently. Before the former United States was unable to contain the virus, and those who’d managed best closed off borders for good—first between former states, then between ten-mile communities. The survivors, at least in our part of the world, what used to be Southern Florida, have lived like this ever since.

Tonight will inspire remembering—when we bathe in rainwater collected on the roofs under the new moon’s first light for Ceremony, soaking our helpless skin to purify our bodies for the new year. It always dredges up years past.

Some people (Lilia) think it’s idiotic that we still do the rituals that were conceived in those early days. Before we knew any better. Dispelling worries privately, every morning, to be carried off by the wind. Washing daily with talcum and salts, especially during seasonal transitions. Gargling with honey. Avoiding other sugars, thought to encourage viral mutation. We’re lucky now to have our own research center for science and medicine in VIISTA, where there hasn’t been an infection in three years. Not so out there.

When I reach the end of our street, I wrap my jacket tighter around me. Hold my breath, exhale sharply, then stretch my arms way above my head and let out the rest of the air in my lungs until they’re completely empty. Because we got through the hardest times with little hope, mother says, we continue to perform the rituals—not because we truly believe they’re all effective, but because if we stopped we might forget our fragility. We must always be grateful, mother says. We do the rituals to remind ourselves we’re still here.

I think we do them to keep busy—to give us a sense of purpose in this desiccated, hollow thing we call living.

I pause at the corner where turning right means school and left means toward VIISTA’s border wall and, further still, the coast. The thing about gratitude is it shouldn’t be a reason to give up on living, that’s what I think—and I mean wild, messy living. Not just surviving.

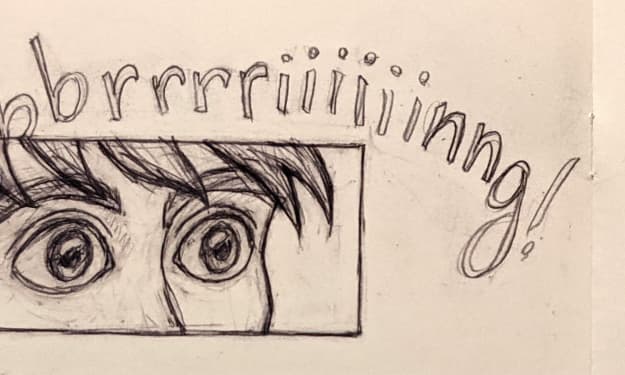

That’s why I’ve been off the vision concession drops for two weeks now, down the sink instead of into my eyes. I’m beginning to be able to see blurry figures, muted colors. Vague shapes, like the imprints of where things once were—only they still are, and it’s my eyes that are just catching up.

The elders say vision concession is a necessary part of life in the after, the Wise Adaptation. Early on they thought the virus entered most easily through the oculus, and the drops create a preventative film sealing off entry. Rates went way down. The problem was, over time they blur, then steal, vision. But the side-effects of this blinding cure were embraced. In the before, the state had ruthlessly sowed distrust. No matter how tolerant we see ourselves, the elders teach, difference, novelty, change—it’s all too dangerous, too easily manipulated, used to justify and distract. Better not to see difference—not to see at all. The elders made vision concession mandatory as a precaution, a preventative treatment two ways.

That’s around when father left. Pieced together from the elders’ stories and the old maps I’m just beginning to make out, tucked away into the diary father left behind, I’ve been memorizing the pictures of the roads, the stars, the markers along the way; learning all I can about the ocean, the waves, how the tides are pulled by the moon. It’s too dangerous, they say. But I feel danger here, more so every day. I feel the danger of minds flattened by fear, of eyes open but unseeing.

I know there must be a way to keep safe but also see. To gaze, to dream, and risk yourself in the dreaming.

A seagull squawks overhead as I take off my backpack and reach inside for father’s diary. A chill shivers downs my back, colder each day now. Mother says the gulls were originally attracted by the nearby landfills, an easy meal after years diving for fish and coming up short. When the fish disappeared entirely, they began nesting farther and farther from the water—they had adapted. For a minute, eyes closed, holding my breath, I think I can feel an ocean breeze roll over me. I try to imagine what it feels like to take the water in your mouth, to taste it, hold it on your tongue like a secret.

I open the diary, leather-bound and wrinkled with time and touch. Out of it fly a flock of paper birds, gray-green and thin. I grab one before it’s taken up by the breeze and bring it close to my eyes. I can just barely make out the visage printed in green ink—a serious, long-faced man. Severe and of another era. I open my fingers to let it go, carried up and away by the wind and swirling higher still.

It’s become a habit, each day before school. I let a paper bird fly, and imagine it soaring back to him. My own private ritual. Inside the diary, dark squiggles and loops dance across the yellowed pages, without meaning. But one day soon I’ll be able to understand them too.

I know he’s out there, living somewhere with others who feel the same way we do. I’ve heard the elders whispering. I am my father’s daughter—and I will find them.

I turn right, toward school. In one month, I should be seeing clearly. In two, I will have memorized the route. In three months, I will be sixteen and I’ll have seen the sea.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.