I’ll never forget the TV anchorwoman’s words to the only survivor of the plane crash: “Please tell us, in your own words, what happened next.”

I’m betting Carmen won’t forget it, neither, though she hardly ever forgets one thing all day. We were in her apartment in Davis, just the two of us, since both of her roommates were otherwise occupied, and we were communicating in a nonverbal way that we both liked, a lot — no words, just a lot of moans, groans and sighs. Okay, once in a while, she made a smart-alecky remark, and we laughed.

She let me up for air and snapped on her TV, and we saw the news story. It seemed that the crash was a few days old, but it was back in the news again because of something freaky: the control tower said the pilot, an older guy about my dad’s age, somehow got the instructions wrong, and he panicked, I guess. The news program played some audiotape of his radio talk; he kept saying, “Say again, Tower? Say again, Tower?”

He didn’t understand a word the control tower was saying, so it seemed, but that tower transmitted in English, and the pilot did, too, so it was a puzzle. “Drugs,” Carmen said. “Got to be. He was high before he left the ground. What do you think, Mister Ortiz?” She was cute when she was being a wise-ass, and the nudity didn’t hurt her case. We had met at the Whole Earth Festival, about a year before this; we clicked, straight away, like if it was that each of us had been given the other’s codebook, or something.

“Well, you would know the law, Señorita Sadler,” I remember joking. “After all, you’re in pre-med.” I was trying to be suave, but the pilot’s story… it reminded me of my folks, and it made me think, who’s going to talk them down safely?

I had to work early the next day, so I didn’t spend the night with Carmen. I drove the dozen miles or whatever it was back to Sacramento, feeling lucky that I didn’t need someone, whom I might not understand, to talk me down out of the clouds, for the few seconds it would take me to crash my plane. Of course, I don’t even fly one.

Carmen’s phone call woke me before I left for the job. “Check it out,” she said, “I just got this text from Shondra. Some dude had this epic meltdown, and just bailed from Professor Skinner’s eight o’clock chemistry class. Guy was ranting about how he couldn’t understand a word Skinner was saying, and meanwhile everyone else is going: ‘Chill out, dude, we can understand him, just fine.’ It takes all kinds of kooky characters to make this zany world interesting, eh, Baz?”

I think my brilliant observation went something like this: “Could be worse. At least he wasn’t flying a plane.” I told her about what I had witnessed, at work; she found the perfect way of cheering me up.

^^^^

“I, I, I, have to go…” I was stammering, in the cooler, in back of the store where I worked, talking on the phone with my mother. She liked to worry about me, a state line and a lot of miles south of her and my father. They did not understand why I had to leave Oregon; I didn’t understand why they stayed, but that’s growing up, right?

I finally hung up on her, and walked to the front of the convenience store where I worked, while I tried to figure out what my real job was going to be someday. It feels good to have parents who worry about you when you’re absent, even if it’s the choice you made: to get out into the world, and seek your fortune.

“Sebastián?” That was Glenn Nakano, a motorcycle cop with the California Highway Patrol. He was actually a cool dude, once I'd got to know him. “Watch my stuff, will you?” he “asked”, which might have bothered me, before I got the job.

Sebastián is my given name; I liked to shorten it, to be more efficient, not to be “cool” or “edgy” (although some customers, and some friends, didn’t buy this, it’s accurate, just the same). Who am I to tell a cop how to address me, right?

I once watched him, from behind my register: he’d dismounted his bike, and removed his helmet, with such... pride; it was like he was making an entrance, like a movie character does. He had looked, well, cool. I’m not usually a big fan of cops, even in movies; I had left my two least-favorite officers behind, in Oregon.

He walked out, through the glass doors, while I moved his cup of coffee and his breakfast burrito to one side. It’s a pleasure, working the day shifts at last, was my thought, at just the moment all of this exploded.

I didn’t see him touching his collar with one hand, and leaning his chin into it, and I couldn’t make out what he was saying, but I knew he was talking to CHP about something law-and-order-y. What I didn’t know, for another five seconds, was that he was chattering with his dispatcher about the car idling next to our gas pump.

I figured out something heavy was down, though, when Glenn — Officer Nakano — started just booking it on foot, across the pavement. He ran around behind the car, and drew his gun. I remember that a new customer, walking to the counter, looked surprised at me: I ran out from my register, to get a view through the doors. I could have gotten myself shot, but dumb luck, it didn’t happen.

Another CHP officer raced his bike a couple of blocks to our parking lot; I swear, he had his gun aimed at the driver, before his kickstand was even deployed. They did a lot of shouting, at the driver — who did not seem to understand them.

The driver had had some unpaid tickets, but when the cops instructed him to get out of his car, he just blanked on them, like he didn’t speak English. Which had to be an odd choice, for a native of California, with no criminal record, and a family sitting on a pile of dough, to make. He had everything to gain by cooperating with them, which is an amazing thing for me, of all people, to recognize.

So they made an arrest, without having to shoot him. Nakano came back into the store, asked the customer and me what we had seen and heard. I told him what I just told you. He shook his head. “What’s the story with him, officer?” the customer asked him, with this goofy smile, like it was exciting to him. Nakano took a sip of his coffee and just blinked, like he couldn’t understand it, any better than we did when he told us.

“He’s just some young rascal, I guess,” said Nakano, who had to be at least in his late thirties… making him fifteen years older than I was, at the time.

^^^^

The tale of the tape: Folks all over the country, pretty much, were getting into all sorts of beefs, for no reason. It wasn’t any one thing, like ‘who you rooted for in the playoffs’, or ‘who you voted for in the last election’, stupid reasons to bitch and fight. Near as we could work it out, it was going on in the offices, schools, restaurants, nightclubs, grocery stores, department stores, garages, bedrooms and living rooms and bathrooms, front yards and back yards. Just another day in history, you say? Maybe you said it; I don’t know.

Carmen thought it was more than just a problem of short tempers, or of bad manners — “I think there could be something medical about it,” she told me, at my place, a week or so after that. “Like it could be a… virus, or something. Contagious dementia?”

I pretended to do a spit take of my iced tea. “A virus that makes you stupid and angry? Well, if you're stupid to begin with, maybe that's a hard life. It would make a saint angry, after a while, I guess. Still, you think this is why older people are losing the ability to...”

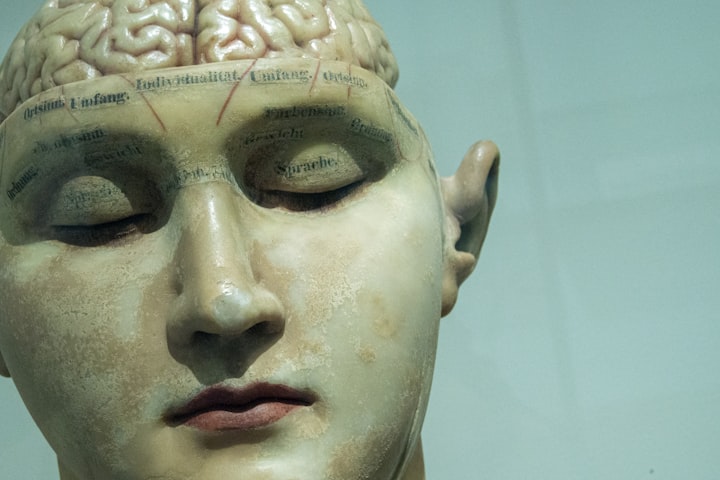

“Sure, why not? I did some research. I’m going to need this for med school, in a few years. Look, our brains are set up in hemispheres. Language is handled by the left hemisphere. You get into what’s called Broca’s area, which is this area, in the back of that, named for a French surgeon, which handles language.

“The back, what we call posterior, part of the left temporal lobe, is named after this German neurosurgeon named Wernicke, and he found out that a lesion in this place could really mess you up, make you speak in nothing but gibberish. Throw in your Angular gyrus in the parietal lobe —”

I was overdosing on her technical jargon, so I laughed: “Okay, okay, but tell me something, will you please, Madame Curie? If you, an undergrad living out here in sunny northern California, can figure this out, what’s stopping the experts in, say, Washington from doing that, too? They’re a lot older than we are, been doing this a lot longer. Think they’ll listen to you? To us?”

“Got to be worth a try,” Carmen insisted, but it took her a moment or two to do that, because she was paying attention, to online news. Some vandals had sprayed a lot of… weird symbols, I guess, on a storefront wall, up in Seattle. The police suspected that gangs or homeless kids were responsible, but its oddest feature turned out to be that a kid about twenty couldn’t make out one word it said, any better than Carmen and I could, so the old policeman did the honors of translating it for the viewers at home: Quit messing with our heads.

“That does it,” Carmen decided. “It's a language thing. Dementia patients act out when they can't get their point across. Problem is to find the causal factor. We’ll look up the Centers for Disease Control, let them know about my theory. What’s the worst they can do, ignore us?” She emailed them, and looked up their phone number, and dialed it with a bright smile on her face. I watched her wait for them to answer. Someone came on, and asked her some questions. She gave them some smart answers, didn’t lie even once, and I was proud as hell of her. She winked at me, saying, “They’re transferring me to an expert in epidemiology.”

Two days later, we were still waiting for that call to come. I was about to give her a lift, back to her campus in Davis, when her phone buzzed. She picked it up, saying in delight: “It’s someone from the CDC — I recognize this number.” Transfer complete. Her smile faded pretty quickly after that. “Come on, this is serious. At least tell me off in my native…” She waited some more, and just squinted, like it was painful for her to continue listening. “Are you mocking me?” she said, and I lowered my drink.

“What’s going on with you, chica?” I asked, feeling like an idiot, which is what I must have sounded like to poor Carmen.

She clicked off her phone and stared at me. “Baz. It’s like they want this to get worse,” she said. “That last woman they put on with me, just now — I could not understand one blessed word she was saying to me.” She dialed the number again, put me on. I had no problem understanding the serious lady on the other end of the line, which caused Carmen's eyes to open wide, in what had to be fear.

© Eric Wolf 2021.

About the Creator

Eric Wolf

Ink-slinger. Photo-grapher. Earth-ling. These are Stories of the Fantastic and the Mundane. Space, time, superheroes and shapeshifters. 'Wolf' thumbnail: https://unsplash.com/@marcojodoin.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.