The Song of Tomorrow

Chapter 1, The Freezing of Eric Fridley

Nobody can hear a scream in the vacuum of space, or so they say.

“To be fair, no one can hear your scream because you are stuck inside that space suit. Also, your scream wasn’t very loud. You are pretty dehydrated right now and your voice is hoarse.”

Who said that?

“Oh, and another thing. Space is not a vacuum, it is a soup of radiation, dust, and anti-matter/matter blips. There is no such thing as nothing. That’s what makes it nothing. So really, there are a ton of reasons why no one can hear you scream in space, but space being a vacuum is not one of them.”

Who said that?

“I said that.”

Who are you?

“That’s not a very polite question to pose to someone when you drift into their home uninvited. I should be asking the questions. Lucky for you, I am highly patient being. Who are you? What brings you into my little corner of the star system?"

I try to twist around, to see where the voice could be coming from. It doesn't seem to be coming in through my ear piece.

“You first,” I say. "I asked you first."

“If I were to actually try to explain to you who I am, it would be even more confusing than not explaining anything. You wouldn’t get it, I’m afraid. No offense. If you'd like to, you can think of me as a fulfillment of the general law: ‘if something is possible, it occurs.’ I am possible. Therefore, I occur. But I know what you are. You're a human. Humans have names. What’s your name?”

“My name is Eric.”

“Eric what?”

“Eric Fridley.”

"Eric son of Fridley."

"No, just Eric Fridley."

Okay. I am hallucinating. It’s only been a few hours but I’m already experiencing auditory hallucinations. Pugnacious auditory hallucinations, too.

“Accusing your host of being a hallucination after, I repeat, you entered their home, is also rude. Although I could tear you apart molecule by molecule, I’m going to be lenient. I know you’re afraid. You may even be panicking.”

Concentrate. Concentrate. Focus on the situation. 1) I am untethered from my ship. 2) I do have a robust supply of oxygen, but 3) I have no water. 4) I am hurtling into interplanetary space, away from the Sun and the Earth. 5) Radio transmissions don’t appear to be going out or coming in. 6) I am suffering from auditory hallucinations due to dehydration and panic.

My synodic rotation period is slow. I’m pitching forward but I’ll be dead long before completing a half-turn. I am facing my ship, a tiny grey shard of slate that stands out sharply against the dark crescent of Saturn. A slice of the gas giant’s bright ocher atmosphere is the only source of light (Saturn’s occluding the sun). Uncountable pinprick stars envelop me.

I press the button in my glove; the empty thrusters sputter uselessly.

My crew is sleeping. They won’t know I’m gone for at least another five or six hours, by which point I will be too far away from the ship to detect.

I try to pick out the Earth from among the many points of light haloing Saturn. One point looks bluer than the rest. Is that it?

“Yes, that one is Earth,” says the Voice. “If you follow an arc to the bottom left of it, you can see the moon, too. Isn’t it beautiful? I have long admired your stupid little planet.”

“Thank you.”

“It’s wonderful to think about how that blue color is the blue of water. Real water. You can see the Earth oceans even from this far. How wonderful it is that your little eyes can spot water from so far away!”

Water. Waterfalls, rivers, pools, pitchers of drinking water, garden hoses, glaciers, puffy cumulus clouds. Fragments of blue pass through my mind.

I will never have another sip of water. Water, for me, is in the past. I will watch all the water of Earth recede until it vanishes. The closest glass of water, apart from what’s in that little ship right there, is three planets away.

“Are you crying? Don’t cry. Please don’t cry. Your situation isn’t hopeless yet,” reassures the Voice.

“I can’t imagine a more hopeless situation than this. In about two or three days I will die of thirst in outer space. My body will rot in its spacesuit.”

“I see a perfectly good ship only seven miles away. It seems like your first mistake was to leave it.”

Seven miles? It looks farther than that. If I can linger here, only seven miles from the ship, and then hang on for another eight or so hours, Annie or Xia might be able to position me and retrieve me. Maybe there’s hope still. Maybe one of them will wake up in the night and notice I’m gone.

It was Sigurd. It had to be him.

“What did Sigurd do?” asks the Voice.

Think, think, think. Focus. Everything depends on keeping a level head.

“It’s clear that my incorporeality is nagging at you, and right now, as you just said, you need to be tackling only one problem at a time,” says the Voice. “Hmm. Here, let’s try this.”

Pop!

With a little comical sound like a finger flicking a cheek, there appears, hanging in empty black space in front of me, Bartleby.

My childhood cat.

Visual hallucinations now. Great.

“Meow,” he says. “I hope this is a welcome image? I tried to use something that was filed under ‘non-threatening’ in your brain, and Bartleby was at the top of the list. Meow.”

“Please stop meowing.”

“Sorry, sorry.”

“Sigurd set me up.”

“How so?”

“He tampered with the space suit. Emptied the thrusters. Lied to me about a damaged panel and severed the line connecting me to the ship.”

“Why would he do these things?”

“...it’s a long story.”

“Is it three days long?”

“No, probably not three days long.”

“Then you should be able to tell it before you die of thirst.”

“You think I’ll last three days without water?”

“Well, I was thinking I might be able to help you with water conservation. I can reroute your urine tubes and send some of it into your helmet cavity.”

“Oh god.”

“You will eventually be thirsty enough to ask me to do that, but I won’t do it a moment before then, I promise,” says Bartleby, with a slow-blink to let me know his affection was genuine.

I picture Sigurd’s grin as he watches me consume my own urine in an absurd attempt to prolong my life. What would he tell Annie and Xia? Would they ask questions? The tether, neatly cut, must look suspicious.

Bad. Bad. My whole assessment of and reaction to the situation has defeated language, and all I think is, bad, bad, bad. No good. Not want. Am I panicking? Is this panic?

“Here’s one good thing,” Bart is lying down on a flat invisible plane, on his back, with his paws up in the air, looking at me upside down. “In about one day, if you can last that long, Titan will drift close enough to you for you to see its beautiful atmosphere, its canyons, its lakes of methane. The light reflecting off the Sun will strike it full on and it will almost blind you with its pure color. It’s one of my favorite times of Titan’s month. Its clouds of pure gold, offset against the white ice of the Great Ring…gorgeous...ice...”

–

...Ice. Ice carried on the end of a hook, dripping clear water onto road-dust that smokes when the drops hit. Down an interstate as narrow as two trucks, not paved.

During the hottest weeks of summer, my little brother and I would sneak into Meyer’s ice house and climb down stone steps dewy with condensation, savoring the cold. That’s what delighted us: the fact that it was not cool, but cold. Not a respite from the heat, but a fair trade of too-hot for too-cold.

If the groundskeeper had found us, dragged us out by the cuffs and stuck us in front of a grand jury with Dr Tucker Meyer himself presiding as judge, we would have been firm in our belief that we had committed no wrong. “We didn’t do it for fun,” we would proclaim. “It was an experiment. We traded extremes to see what it would do to our bodies.”

It’s amazing how rapidly and completely we forget a sensation. When it’s hot out, you cannot recall the cold. When you picture the smell of grass, you are not remembering the smell; you’re remembering how it made you feel. A sensation is a creature without memory. It cannot venture outside the moment.

Marcus and I would carve a block of ice for ourselves, careful not to make it too big, then bring it back home. We’d stick it in the ice box. Mom would ask no questions.

One time, dad caught us coming home with a block of ice on the end of my hook. Marcus had spotted him first, and ran behind the house.

Dad put the ice in the ice box and locked me in the shed.

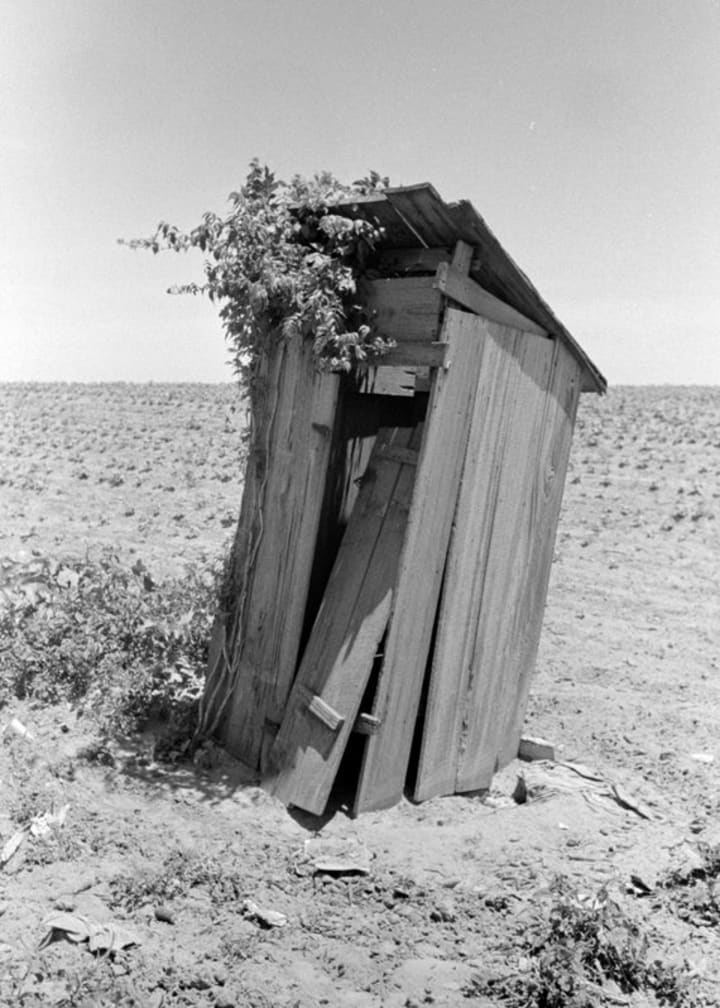

For the rest of the hot afternoon, I stood in a space too narrow to lay down in or even sit in comfortably. I was hard to breathe. The heat inside the shed climbed until I thought I would pass out. I managed to punch out a knot in one of the planks of wood in the side and could breathe a little through this. It was dark in the shed, except for one shaft of light that came through a fist-sized hole in the top corner. There was an old bird’s nest beside the hole.

After sunset, the temperature in the shed fell rapidly. I began to shiver. I banged on the door and screamed to be let out. But nobody came. Once, I thought I could hear soft steps outside. “Marcus?” I whispered. “Let me out. I’m dying.” But the steps scurried away. It might have been an animal. Soon after that, I heard a little meow. “Bartleby?” I whispered. A confirming trill and a sound of a soft body pressed against the door. I stuck a finger through the space between the bottom of the door and the ground. A tiny claw poked it. A scratchy tongue licked it.

“Bart, let me out.”

The cat soon got bored and went to find a better playmate.

The hours wore on. Through the knot I could see only one window in the side of our house; it was dark. Had my family left? Had they caught a train, in order to be as far away from me as possible? Was it not enough to leave me in the shed to die, they had to go to the other end of the world, to abandon me as superlatively as they could? Or maybe something terrible had happened to them. Maybe a killer had come while I was locked up and annihilated all of them.

The blackness in the shed was almost complete. The hole in the roof showed the deep blue night sky. Stars processed across the hole slowly, one or two at a time. I counted them. Once, maybe around midnight, the top sliver of the moon spilled over the bottom of the hole. By its white light I read my palms. I tried to interpret the lines. When the moon passed after only a few minutes, I felt like a prisoner whose visitation rights have been suspended.

I began to shiver, and curled up in a tight ball against the door. Suddenly, I was certain that I would die of cold very soon. I started to scream. If I screamed as loudly as I could, maybe they’d realize that they were actually killing me. The purpose of the punishment would be moot if I died from it, surely? Or maybe the neighbors would hear me. Or maybe I’d wake the chickens or the dog or someone passing through our lot in the night. I screamed and screamed.

“Help me!”

I had to come up with a plan. Something I could do here in the shed, with no resources but my own mind and body.

Here’s what I resolved to do: if I could erase my mind completely, even for just a moment – if I could empty myself of every thought – I would no longer experience time. My mind, now a vacuum, would be connected directly to the point at which a new external input was given, namely, being freed from the shed.

I sat on the dirt as comfortably as I could, covered my eyes, and tried to clear my mind. But try as I might, thoughts would enter unbidden. I thought of my brother, ditching me just before dad showed up. I thought of the feeling of the cold in the ice-house. I thought of the stars. Mostly, I thought of myself, and the pitifulness of my situation. Always my thoughts would return to my self.

My plan failed. Try as I might, I was incapable of emptying my mind. I sat and cried for awhile.

Before the roosters announced morning, just as a tinge of pink was beginning to show through the hole in the roof, the shed door opened suddenly and I tumbled out on the cold dirt.

This is the end of the memory.

I can’t remember who opened the door. I can’t remember the feel of the morning air, or the smell of the grass. I just remember the door opening, and falling against the ground.

The stars that had, one-by-one, sat with me during the night and kept my loneliness from being complete, now disappeared, one-by-one, into the pink dawn sky.

–

Stars in a black sky. A Cheshire grin of pale orange. A grey ship. A blue dot.

And Bartleby.

My tongue is swollen. It feels like a strip of leather.

“Good morning,” Bart says.

“How long was I asleep?”

“About seven hours.”

“Why didn’t you wake me up?”

“I thought it would be the simplest solution to your problem to let you die in your sleep. That way your suffering would end. But unfortunately, you didn’t.”

This passes for compassion in outer space! I’d laugh, but my tongue is too swollen.

“Do you want to drink your pee now?” Bartleby asks.

“Not quite yet, thanks. Hey Bart. Earlier you said you had an idea. Is that really true, or were you just trying to perk up my spirits?”

“No, I really do have an idea. It’s kind of a last-resort idea though.”

“What is it?”

“...To freeze-dry you.”

“Freeze-dry me?”

“Freeze-dry you.”

“What does that mean?”

“Basically, I can open your helmet long enough to freeze your body. Then, once you’re frozen, I’d close it again so that your body isn’t destroyed by radiation or sucked out of the suit or anything like that. Then, freeze-dried Eric Fridley can drift through space until someone finds him and unfreezes him.”

“That’s the worst idea I’ve ever heard.”

“I told you,” Bartleby said with some annoyance, “it’s a last-resort plan. Its success is contingent on the possibility that you will be found by an advanced technological civilization that can restore you to animation. Your body will float through space indefinitely. So I figure, might as well let a future civilization find a preserved astronaut rather than mush in a spacesuit. It may take several billion years, but since you’ll be frozen, you won’t know the difference.”

Several billion years. An incomprehensible duration.

Bartleby chuckled. “Oh, you humans! You’re so bad at time.”

“What do you mean?”

“You assume everything – planets, stones, rocks, bugs, space itself – experiences time the same way you do. You speak of the ‘age’ of the universe, like the universe is some old person with a white beard. There is no billion years. A planet doesn’t experience a year. A star has no sense of its rotation around the galactic center. Time is the thing a clock measures. A billion years as a freeze-dried corpse will be precisely the same experience you had just now, of falling asleep and waking back up.”

“There are a lot of ways of looking at time,” I retort. “I guess that’s one of them. But a billion years by any vantage point is an immense expanse of time, if we think of time as a set of events. Think of how many particle collisions occur in that duration.”

“But does a particle look at its watch?” Bartleby asks. “No. I repeat, freeze-drying you would provide you with a direct link to a billion years in the future. A temporal short cut. A brief cut. A cut of brevity.”

I notice, finally, a golden-yellow half-circle in the corner of my eye, sitting just below the harsh grey line that represents my edge-on view of Saturn’s great ring.

“That’s Titan?” I ask.

“Yep.”

“Any aliens in there? Under the atmosphere?”

“None that I’ve ever seen before,” Bartleby shrugs. “No one’s ever poked their heads out of one of the canyons or come flying up on a plume of methane. And yet it is a gorgeous moon, though lifeless. It’s a cutie, you can’t deny it.”

“If you freeze-dry me,” I ask, slowly, afraid of the answer, “and my trajectory through space happens to be such that I will never be found by any alien civilization, then I’ll never wake up.”

“That’s right.”

“I might float forever, until the atoms in my body expand with the expanding universe and I sublimate into errant photons each a billion light years from the other.”

“A bit dramatic...”

“I might hit an asteroid next week and be pulverized.”

“I’ll do my best to set you on a trajectory that will avoid such collisions, but it is an appreciable possibility.”

“But if I am found, then I’ll just wake up. As if I had only just gone to sleep.”

“Yes. And I think that is an appreciable possibility too. Because to other observers, a billion years allows for a large number of eventualities. Your ephemeris may take you past a planet with capable scientists just itching to defrost you.”

"So it's like going to sleep before a surgery," I say, "only you have no ability to know the likelihood that you'll die on the operating table."

"Yes, metaphor-creating human," Bart sighs. "It is comparable to that."

“But I’m going so slowly! I’m not Voyager 1 or 2, hurtling along at a decent 15 kilometers per second. I’m inching away. One mile an hour. A billion years gets me to Alpha Centauri. Maybe.”

“Oh, don’t worry about that at least. I can give you a good push and get you going pretty fast.”

“You can do that? How?”

“O ye of little faith! It’s enough that I can do it. Here, I’ll prove it. Do you see that lump of rock over there?” Bartleby sticks his tail straight out into space. I follow it, but can see nothing but pure darkness. “Well, there’s a rock there,” Bart says shortly. “Just wait a bit.”

Slowly a large, irregularly-shaped hunk of porous space-rock drifts into view, dimly illuminated by the light of crescent Saturn. Relative to me, it moves slowly and gently, passing maybe a hundred yards away.

“Watch.”

Bart trots over to it – just the way that the orange tabby of my youth would confidently trot toward the front door at the end of a day of prowling through the farm. He reaches out an exploratory paw, as if it were a glass on the edge of a table. In this manner, he brings the space rock to a halt, then alters its trajectory to move toward me. Then, Bart winds up, and swats it; the rock, now on a different path through space, passes me at a gentle rate.

“It’s speed will increase gradually until it reaches about 50 kilometers per second,” Bartleby says confidently.

“Increase? How? By what force?”

“I will follow it.”

“You will?”

“Well, no, because I’m here with you. But I mean in theory, I’d follow it and increase its velocity until reaching the desired speed. So with you, if you choose the freeze-dry plan.”

“You mean you’d follow my body? Keep it company?” I remember little Bartleby sitting by the shed door with me.

“At least until the edge of our star system. Beyond that, I have no power.”

Let’s weigh the options here, I think. Option 1) do nothing. Drift in space until I die of thirst. Option 2) wait…

“Wait!” I exclaim. “I must be delirious for not thinking of this immediately. If you can really move me, just bring me back to the ship!”

To my surprise, Bart’s tail puffs up. He arches his back and his pupils expand to fill his eyes. “Hmm,” he growls. “I don’t think that’s the best idea.”

“Why not?”

“Well... I didn’t want to show this to you, but I guess I have to.”

Bartleby steps lightly over to me, slow blinking, and puts a paw on my back – I feel its pressure, firm and direct – and begins to walk toward the ship, carrying me with him. About halfway over, he moves his paw to my chest, to halt my velocity. Gracefully, after a few minutes, we come to a stop in front of the ship.

The McKinley, built in Earth’s orbit, is frankly hideous. Engineers liberated from aerodynamic considerations took the ship’s asymmetry to a rhetorical degree. You’ve got a central orb about the size of a high school gym, which is one big room filled with lab equipment on different catwalks and platforms. Much of the orb is glass.

Out of the left side of the orb issues about half a dozen tubular extensions about twelve feet high each. They run out in different directions for a few hundred yards, sometimes bending at different angles, and end in big boxes. Each box is a quarantined lab, and the tubes that connect the labs to the orb are filled with decontamination chambers. One of the tubes is short, and goes right to a large cube that contains our living area, which has a dorm, a cafeteria, an exercise gym, and a recreation area.

From the other side of the orb issues a thick arm that connects to the engines. They’re powered by nuclear fusion. No harebrained EmDrives or anything like that in our ship; just good old-fashioned brute power.

We go right up to the dormitory windows. Bartleby begins to purr.

I look in.

God.

“Turn me around,” I say after about one minute. Bartleby gently pushes my shoulder, and now I face empty space. Titan sits against the field of stars.

“It doesn’t make sense,” I say finally. “He’d been acting strangely, but nothing suggested a psychosis of this level.”

Annie and Xia could have been sleeping. They’d been put in the same bed, their arms interwoven.

The knife had been left on the sink, neatly parallel to the edge.

“Sigurd, if that’s his name, is in the bathroom,” Bart says gently. "Been in there for a while."

“So he lies to me about a malfunction and gets me out here for a phony spacewalk. Then he does this. Gets them in their sleep.”

Bart nods.

“Ground control,” I continue, “likely watched the whole thing. Jesus Christ.”

Suddenly I want out of this spacesuit. I mean obviously I wanted out of it before, but now I’m panicking. I need to get out of it. I need to clean up that mess in there. I need to get on the phone with ground control. I need to walk around a bit. I need to lay down.

I need a drink of water.

I need a drink of water. If I can only have one single glass of water, then everything will be alright. What happened in that ship is only a manifestation of my thirst. My thirst killed my crew. My thirst is a murderer. My thirst is the whole world, the whole universe. This fucking disembodied voice, this hallucination, is thirst.

I press my helmet up against the window.

Suddenly the bathroom door opens. Sigurd, naked, freshly showered, walks out into the dorm. He glances briefly at Annie and Xia, and then he looks out the window - directly at me.

“Bartleby,” I say slowly. "I have a better plan. A way better plan. Open that fucking space-ship door. I want to have a little chat with a coworker."

About the Creator

Eric Dovigi

I am a writer and musician living in Arizona. I write about weird specific emotions I feel. I didn't like high school. I eat out too much. I stand 5'11" in basketball shoes.

Twitter: @DovigiEric

Reader insights

Outstanding

Excellent work. Looking forward to reading more!

Top insights

Compelling and original writing

Creative use of language & vocab

Eye opening

Niche topic & fresh perspectives

Excellent storytelling

Original narrative & well developed characters

Expert insights and opinions

Arguments were carefully researched and presented

On-point and relevant

Writing reflected the title & theme

Heartfelt and relatable

The story invoked strong personal emotions

Masterful proofreading

Zero grammar & spelling mistakes

Easy to read and follow

Well-structured & engaging content

Comments (12)

This was so captivating and unpredictable! Loved it!

Whoaaaa what a cliffhanger! I need to know what happens when Sigurd and Eric meet again. Poor Annie and Xia. You did a fantastic job on this story and I loved it!

A very enjoyable read. Well done.

What a trip! Fantastic! Hearted & subscribed!😊💖💕

Wow! There was so much going on in this story, and I appreciated all the layers. I'd definitely read a chapter 2, well done :)

Very creative, now for Chapter 2? 🥰

How are we in the same group? I feel like I'm in the wrong class, lol What a fantastic storyline. I loved the conversation and the flashback memories. I especially enjoyed the uniting of spirits proceeding to the next chapter.

Wow! I look forward to reading more of your work.

Excellent!!!!

Wonderfully atmospheric and suspenseful with a great ending. Fab concept. 👍👍👍

That was SUPERB. I subscribed so fast my head spun.

What an Odyssey! This was such a journey. Clearly a ton of time went into crafting this. Well done! <3