The Potter's Field

originally published in Body Parts Magazine

Eduardo chips at the soil with the tip of his broken shovel. The end of it is jagged, and there is no certain angle to strike with in order to break into the snow-dusted earth. His hands are cracked painfully from the harsh winter wind, and even though he knows working harder might warm him up he hesitates, as usual, to do so. Even more today, because it isn’t like the movies, where he’d need to paint tally marks onto his cell walls to keep track of time, even though he wishes it were. He wishes the answer to his anxiety was as simple as an untallied wall, but he knows exactly what day it is. It’s the date some doctor scratched aggressively with an almost dead pen onto the blank space beneath a picture of white noise that Eduardo’s girl insisted was his baby. The etched in due date that’s been seared into his memory just as harshly as it was written on that photo.

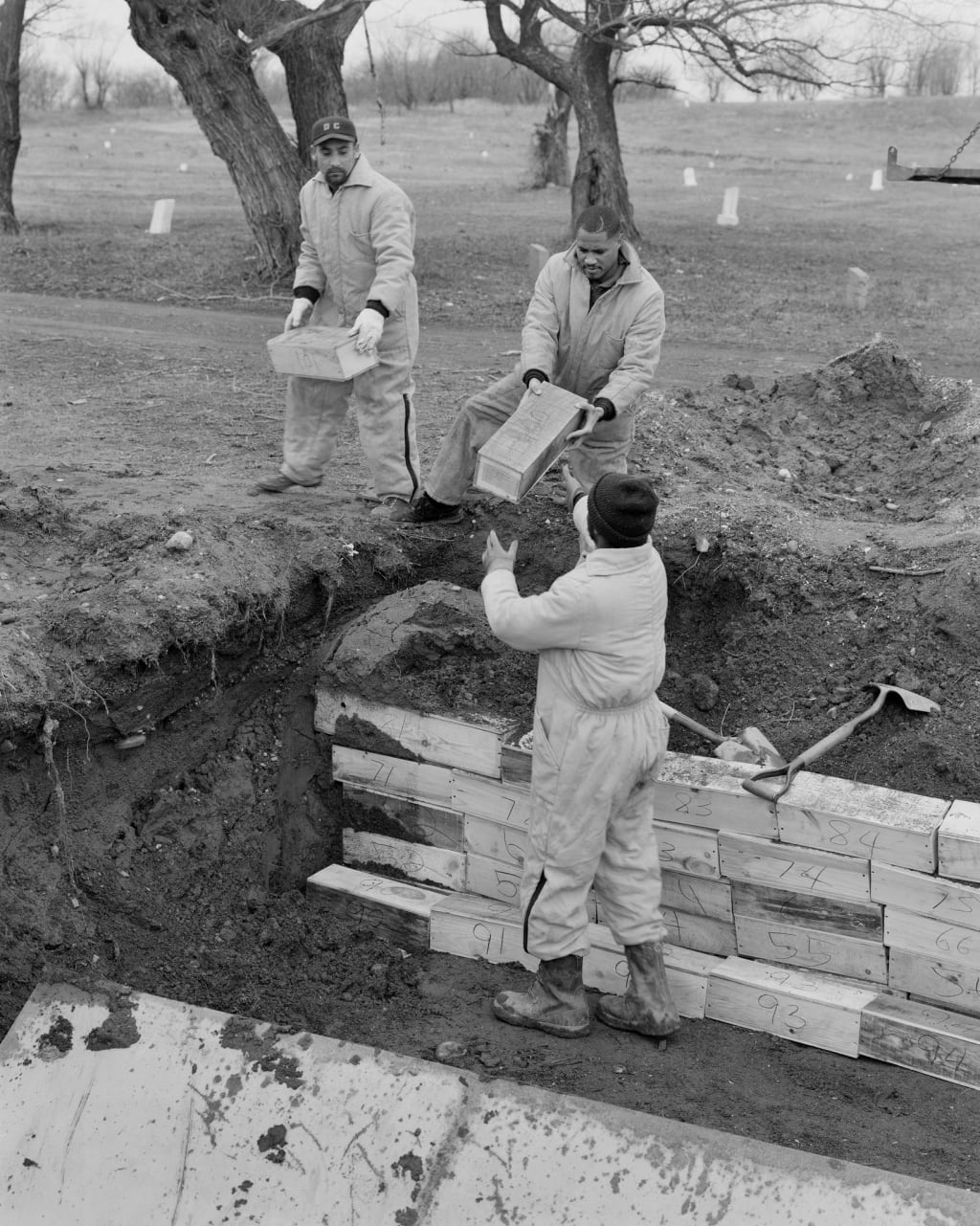

So, he doesn’t mind the trouble the shovel gives him. In fact he often takes his time getting into line for one, so that the others will take the biggest ones, the sturdiest, first. They always fight for the one with the red, rubber handle, complaining about the exceptional pain they’re in, doing each other favors for a better spot in line, so they can finish their two simple jobs for the day: digging and stacking. But Eduardo hangs back, hoping for a nuisance, something to deter him from getting to the second task, which is to help unload the boat, stack the coffins up. Three high, six across.

The large pine boxes are not so bad, where they place the ancient street sleepers who somehow stood the test of time, outlived their relatives who may have taken pity on them if they’d heard of their inevitable demise, and then finally died alone. The large pine boxes where the disowned meth heads lay, the unfortunate soldiers, those corpses who were too mangled to be recognized, or people too embarrassing to be collected.

Among them, those nearly one million coffins that have been dropped into the trenches and just keep adding up, are even some famous people. Writers, actors, directors. When he was first assigned to potter’s field duty, someone in the cafeteria had told him Peter Pan was buried there. “Like the kid who did the voice, you know?” he’d explained just as Eduardo was about to write him off to insanity.

“I’m telling you, you got yourself a Cadillac job there, Avalos. You never know who could be coming down on those boats,” he’d said through the instant mashed potatoes crowding his mouth. He shook his head as if jealous as he finished his meal. “You never know.”

During Eduardo’s first days on Hart Island he’d tried to imagine who it might be that was contained in each box that was passed from the unloaders’ arms into his own and those of his partner. He tried to think of it as something glorious, to hold the wrecked body of a creative genius. To be the last to connect with them, to handle them as he liked, lay them down gently.

But after a few weeks, when the leaves on Hart Island would have begun to change if there were any, his body ached and it became harder physically to set them down lightly because his back was spent and his joints had started folding apprehensively like a rusted card table chair. By the time he got to the last coffins of the day, he found it easier to pretend that the bodies inside were never anyone important at all. Even easier to pretend that what he was placing in the dirt was a box full of potatoes, oranges, anything but human remains.

New inmates who were assigned to the potter’s field after him would sometimes pray over the coffins. Some of them would sing or even cry. Some of the more disturbed men would make jokes, but after long the island would return to its quiet, until the next boatload of newcomers came in. Eventually they all learned to keep their heads low, to get the stacking over with and boat back to their cells anxious for their next opportunity for a phone call or a visit, to make certain they wouldn’t end up forgotten like the boxed up seeds they sow every Tuesday through Friday afternoon.

But Eduardo is not bothered by the idea of eventually being dropped haphazardly into a potter’s trench dug out by some criminal, set down among the other unremarkables, unlovables, and unidentifiables. What he hates, what he is avoiding as he rakes anxiously at the freezing earth and the wind laps loudly at his ears, is when the little mismatched wooden coffins will be passed over from one inmate’s hand to another. Each one a different size. Not regulation like the pine ones. Sometimes the size of a shoebox. Sometimes no bigger than a loaf of bread.

“How’d these babies get here anyway?” he’d asked the others early on.

“You know, some homeless chicks’ miscarriages and shit.” His partner shrugged, pausing to stack another box. “Probly a bunch of dope babies.”

“You never know, I guess,” he’d thought aloud.

When he’d been taken to prison, his girl had already left town with a swollen belly. She stood in the doorway saying she was worried, saying she didn’t want to go down with him.

“No,” he’d said, “you don’t want to go down, you just want to get down.”

He knew that she was really worried that he’d make her quit. She didn’t want to quit the dope. Could he be mad really? No one wanted to quit the dope, and he’d sold it to her in the first place. But she had his kid in her and she still didn’t care. She’d do anything to keep using, and since her supplier was the father of her child and had no intention of continuing to keep her in the daytime, she took her chances to find someone who would, and she left.

He didn’t know where she’d gone, no one did. She’d vaporized without leaving anything but Eduardo behind. Days before his operation was busted up, he was looking up what happens to babies whose mothers use heroin. Maybe they’d found him out because of that search, but the longer she was missing, the less it seemed like she’d be back, and the more desperately he wanted to know what his baby might end up like.

Now he still doesn’t know and won’t know what his baby is like, but he knows the baby might not have a chance to be like anything at all. He doesn’t know if he is light-eyed and big-boned like he is. He doesn’t know if he’s impulsive, quick to anger. He doesn’t know if the kid is the size of a shoebox or a loaf of bread, and every time he lays his broken hands over one of those little boxes he flicks anxiously at the nails holding it together like some kind of terrible tick. Every single time another little box comes down the line to him he is overcome by a horrible desire to pry the sides of the poorly constructed container open and search the face of the baby inside for some telling sign. So he could at least say he was sorry if he found him. So he could at least kiss his little face and be the last one to touch him. Not through the box but on his flesh. Run a thumb across his forehead, feel the pillowy top of his cheek with the back of a finger. Because if Peter Pan was somewhere in the stacks, he’d think, how could you know who’d come in next?

So this is how he copes. Scratching at the dirt when no one is looking, only digging when he is watched, until someone realizes he isn’t helping and yells to him. Until someone calls out to him to hurry up and help unload the infants and he has to wonder if the little box marked B706 is his son or daughter, and if not, who it is that he’ll have to place snug against B705 like a brick in wall.

It’s been nine months since she’d told him she was pregnant behind a shield of metallic smoke. The day he demanded that she stop. The day she said that he didn’t have to stop so why should she, if she only did it sometimes. Only every now and then. The day he lifted his hand to hit her, but she ducked faster than his clouded mind could calculate, and once he picked himself back together he was alone.

“Avalos!” An officer is calling to him from shore.

“Get your slow ass down here,” a peer yells.

The boat is slowly rolling in behind them. Eduardo quickly digs five wholehearted times into the hard ground as if he’s been working hard all along, as if he’s working so hard that he can’t hear them. The wind whips up again, and he makes the mistake of following its cry and glances down toward the others. He’s caught in a hold of eye contact with an officer who dips his head in the direction of the boat, as much a warning as this officer is known to give. So despite his growing anxiety, Eduardo drops his defective shovel, looking back at his tiny hole, his day’s work, and walks down the side of Cemetery Hill toward the others.

“We almost missed you up there again,” the officer says, hardly moving his mouth, warning Eduardo that he is far from oblivious.

Eduardo nods once acknowledging the comment, rubbing thumbs against forefingers nervously. He heads to the back of the line, being watched by two hot eyes at a time as he gets there, and his knees shake inside his pants, not from the cold but from his nerves.

He knows his baby could have already come through here. He knows the baby may have ended up somewhere else, but today feels closer. All day he’s been hearing wailing in the wind, a desperate crying out for Eduardo’s care. His baby’s plea to touch him just once, hold him like he deserves to be held.

Everyone is moving quickly. Racing the weather. Whatever weather is coming they don’t know, but they can feel it in that harsh gusts and in the way the officers are anxiously watching the clouds like they know something the inmates don’t. Because they do. Because they watched the weather channel last night next to their wives as their children slept.

Before he’s ready, Eduardo finds himself next to the boat, and when he causes a hiccup of time to pass before taking what is held out to him the unloader shakes it a little in his direction. Eduardo grabs the reddish wood box marked B881 if only to rescue it from being handled so roughly. The crude container is bound with nails in the corners and the sides of the lid. He slowly walks it over to where the others are quickly stacking up and filling in a trench, trying to get the day over with and stay warm. He tries to concentrate on his destination but notices one of the nails is bent up awkwardly. He wedges his thick thumbnail under that mis-hammered tack. It wiggles gently, and the corner of the lid raises up just the smallest bit.

Someone snatches at the side of the coffin, only looking up when Eduardo doesn’t let go. “Avalos,” his fellow inmate says, pulling back on the box hard, his bottom lip quivering from the dropping temperature as he looks over his shoulder anxiously. “Hand it over, man.”

And Eduardo wants to, but the cold has finally turned his hands to stone and that nail, that bent up nail, is curled towards him like a beckoning finger, inviting him to take the baby lying inside somewhere better than a 6 foot trench. A trench for the unlucky children who didn’t do anything to deserve to be so unlucky. Children who were drug addicts against their will and ended up with no better a fate than an apple core in a land fill.

Eduardo pulls down with all his force. “Fuck!” the other inmate cries, left with red splinters in his hands as Eduardo breaks out running up Cemetery Hill. Where he is going he is unsure. Maybe he could run to the opposite shore and set the baby out to sea, let him sail back towards the Bronx where someone might bury him properly. Maybe he could get him out and swim him back himself. He trips and falls over the little hole he’d dug. His knees connect harshly with the ground, and he begins to cry onto the top of the coffin, digging at that little space between the lid and the box until his fingertips come away spotted in blood.

He looks out towards the big, busy city just as a few fat snowflakes start to fall, and he knows there’d be no one waiting for B881 over there, because his father’s stuck here on the island of the dead. With no one to catch him on the coast, the baby would be washed up, found without anyone to claim him, and he’d end up here again. Even if Eduardo wasn’t about to be hauled off the island, even if he could somehow place the baby in the water, the wind has begun to die down anyway and the little box might just rock slowly back to these haunted shores.

The officers are coming up the hill so he presses his chapped lips to the box and tells the boy he is sorry, he is so sorry, and he drops the box into the hole as someone grabs him up by his coat. As he is being dragged away, he kicks dirt over the box trying to conceal the baby, trying to save him from the potter’s field. But it’s too late. He’d buried him there long ago. Even if he hadn’t helped dig the trenches, even if he’d always tried to avoid the boats, he’d landed his baby in the dirt anyway.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.