The Last Warrior of the Mythopoetic Men’s Movement

remembering Dad

Are fathers harder to understand than mothers?

The movie star Will Smith admitted he considered killing his abusive alcoholic father.

My dad was not a drunk but he was psychologically abusive. I wished he might die more than once.

Dad is a man of course. So there is that touchy-feely male bonding thingy. Guys do have a problem getting their arms around it. (no pun intended)

My coming-of-age male role models included Alan Watts. Jack Kerouac. Herman Hesse. Jean-Paul Sartre. Lawrence Ferlinghetti. Maynard G. Krebs. Spock. Ray Bradbury. R. Crumb. Gandalf. Richard Brautigan. Aldus Huxley. Henry Miller. Soupy Sales. Frederick Nietzsche, all the Marvel Comic Book male heroes, and many rock stars too. Too many to list like Jim Morrison and Jimi Hendrix.

A typical testosterone-filled, patriarchal narrative.

I didn’t understand where my dad fit in.

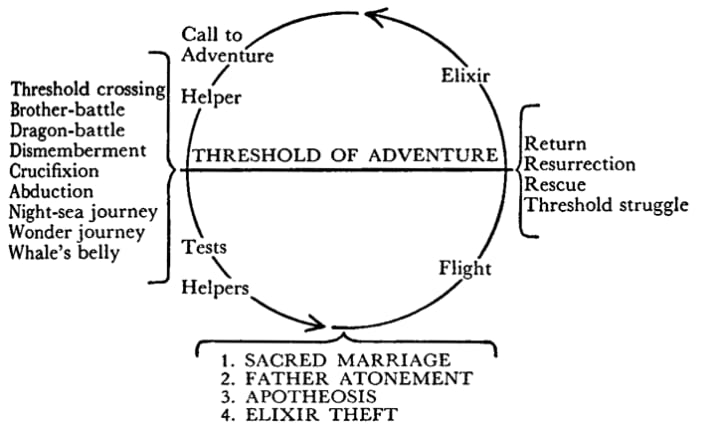

It pains me to admit that I grew up with missing Zeus syndrome. Adding to the mystery about why the male gods frequented the bed chambers of mortal women. Impregnating them. Then ran off on their children? Half-God/Half-Human. The male child faced their hero journey alone. With a little help from magic dad they defeated their demons and walked the hall of apotheosis.

2,000 years later the story hasn’t changed.

According to David Brooks, the author of the article “Why Fathers Leave Their Children”, fathers don’t simply abandon their families out of laziness or lack of love; they leave because they feel unworthy. Fathers tend to go into parenthood with unrealistic standards, which ultimately sets them up for failure.

My dad felt unworthy? I don’t know about that. Zeus more likely.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 18.3 million children, 1 in 4, live without a biological, step, or adoptive father in the home. Consequently, there is a father factor in nearly all social ills facing America today. — Fatherhood.org

The modern world is more complicated than ancient Greece. There was a need for new ideas.

During the 80s-90s. Authors Robert Bly and Joseph Campbell. Tried to bring men together through their experimental Mythopoetic Men’s movement. The movement was a body of self-help activities. Therapeutic workshops and retreats for men. In these retreats, men would camp out and wear war paint, pound on drums, and hug each other.

The most well-known text of the movement was Iron John: A Book About Men by the poet Robert Bly, who argued that “male energy” had been diluted through modern social institutions such as the feminist movement, industrialization, and separation of fathers from family life through working outside the home. Bly urged men to recover a pre-industrial conception of masculinity through spiritual camaraderie with other men in male-only gatherings.

In Bly’s book he also introduced the idea that by releasing a man’s Zeus energy would bring him more in touch with his feminine half?

I tried that idea and my dad called me a fag. The men’s movement (RIP).

I want to remember my dad. Ok. He wasn’t a God. But I want to share what memories I have. I apologize in advance if you find this story disrespectful. I refuse to bend the truth to appease relatives.

Missing Zeus

Late one night during a chilly Indianapolis November. I was asleep in an apartment or hotel (I didn’t know) and my dad woke me up. I hadn’t seen him in a long time.

“Here’s 10 cents. Go down to the street and get me a newspaper,” Dad urged.

I got as far as the lobby door and froze. I was too scared to go out and ask for a newspaper. My dad was behind me, and he took me out to the street.

We didn’t have jackets and I started to shiver.

“John F. Kennedy elected president,” the newsboy announced, “read all about it!” His voice was hoarse from shouting.

“Hand him the 10 cents, son,” Dad encouraged.

I gave him the dime and the hawker handed dad a newspaper.

“Damn Democrats!” Dad mumbled after reading the headline.

The next memory of my dad came a year later. My parents were watching TV. I came into the room and complained that my groin hurt. My dad pulled my pants down and rolled his eyes. My testicles looked like purple grapes.

“What happened to you?” Dad asked.

“I fell on my bike,” I grimaced.

“It would appear so,” he said.

“Get a bag of ice,” he told Mom.

She handed me the ice, and told me to place the bag between my legs, then go and lie down. That was the last memory I had of my dad for the next several years.

Like Willy Loman in “Death of a Salesman.” Dad never made his sales quota, so every few years he uprooted the family in search of a new job. Always in search of the American Dream and the next big close.

When I was in the middle of fourth grade. We settled down in the Minneapolis suburb of Burnsville. A beautiful new housing development called River Hills. Shortly after the move from Cedar Rapids, IA. Dad enjoyed a long, winning sales streak until that very sad night that, once again, would uproot us all.

One evening the police found my dad face down. Unconscious in a country road ditch. Nowhere near his car, running at a deserted intersection. He had a large, grease-covered lump on the back of his head.

After the accident. He lost his job.

Thus began the daily ritual with a tall glass of orange juice and a long game of Solitaire in his bathrobe.

Later he sat in a red linoleum chair.

Passed his days chain-smoking Lucky Strike cigarettes. Watching Lawrence Welk’s “champagne music” reruns on TV.

My dad’s hospital bills and his inability to work landed the family in bankruptcy. Like the game of Chutes and Ladders we kids played, wherewith the roll of the dice we went down the slide to climb back up. The fighting between my parents intensified with the growing bills. We needed books and clothes for school. Utility bills piled up and mortgage payments lagged.

After the American Dream home lost. Dad appeared at the table of our low-income. Blue-collar neighborhood rental house. Smacked me in the head, and ripped my writing from the typewriter.

“Where is this shit going to get you?” He shook the paper at my head as my fifth-grade principal did. Made it into a ball and was thrown against the wall. “Are you homosexual? Is that it?” he hollered, as he read the letter and mocked me, “Dear Lawrence Ferlinghetti . . . how sweet. Is this man your lover?” He pushed me like the bullies at school did.

“No, Dad. Allen Ginsberg, but not Ferlinghetti,” I replied while laughing at my joke.

“The Navy will straighten your ass out you little faggot,” he swore. Pointing at me like a prosecutor reading off the sentence. “No son of mine is going to be homosexual and live under this roof.”

Dad rarely spoke.

Often going days without so much as uttering one word. Then scare the bejabbers out of everyone. When he would wake up in front of the TV. Start rocking in his chair, “Fucking queers, Mexicans, niggers, communists, hippies…!” and those are a few rants I recall.

In middle age, my dad still had a trim upper body and legs. When he could afford it, he also used to play golf.

Dad was handsome, of Danish descent. A white supremacist of average height and build.

I thought he resembled a cross between Rod Serling’s bushy black eyebrows. And James Bond’s neat as a pin haircut, shiny fingernails, and hairy arms.

The cigarettes, head injury, and the TV had taken their toll. My father grew a gut.

Regardless of the many ups and downs in my dad’s life to his credit, he did not reach for the bottle.

When he moved too fast, he wheezed out of breath. He wore one hearing aid on the right ear, which was a Purple Heart medal reminder from WWII. My mother claimed he needed two hearing aids. He would turn his head to the right and say, “What?”

Dad’s war injury may have left him deaf in one ear. But, through the veteran’s disability, he received money for his suffering. Through his unemployed periods, and convalescence. The VA helped our family to remain afloat.

One of dad’s best attributes was he had all the charisma of a sales closer. He had the buy-in smile and unflinching eye contact. An authoritative and articulate, sign-on-the-dotted-line voice- and a firm, done-deal handshake. He also had the gift of charm, which he could use to influence the less informed (or women). I hated to see his chair-bound body and hoped he would again return to the world of a positive mental attitude.

A former national sales trainer in personal insurance. He had purchased life insurance policies for us, four kids. When the chips fell he canceled them and never put one on himself.

“You destroyed my English assignment, Dad,” I rebounded. “I was doing my homework.”

“Do you even go to school?” he countered. “I don’t see any books. What are your grades?”

“I signed up to take an independent study this quarter,” I replied, crossing my arms. “I was writing a letter to the author of a book I am reading called, “Tyrannus Nix.” It’s a long-form rant on President Nixon. You should read it, instead of being lost in your Lawrence Welk. I was almost done until you ripped it up.”

“You know what happens to young men with a smart mouth in the Navy?” he warned.

“No, Dad… what happens? Face court-martial? Thrown into the brig like my brother? Wanted by the military police like he is now?” I retorted.

My brother had gone AWOL from the Army a month earlier and no one knew his whereabouts.

“I’ll deal with your brother all in good time.” Dad continued, “Right now, keep your nose clean smartass or I’m going to have you hauled away like last week’s garbage.”

“Give peace a chance, Dad,” I chanted as they did at the anti-war rally.

“My God, you sound like a queer,” he concluded, shaking his head.

“Power to the people,” I said, flashing my dad the peace sign. He grabbed me by the shirt, and added, “Don’t tempt me, boy.”

Despite his mixed-up shortcomings, I loved my dad. Before the accident and unemployment, we did do normal family things like go on vacation to a lake cabin. He rented a boat and would take me fishing. He built me a bike. Brought home a miniature road race set. From his travels, he’d given me a TWA captain’s hat and pin. In the earlier days, he would play cards with me and my brother’s friends.

Hard on a guy’s ego are the mini moments that you never forget. Like when you dropped out of baseball because you were the strike-out boy. The other dads watched the game and gave their support. You were an embarrassment on your own learning how to be a man.

I knew somewhere in there was my old dad- the flamboyant, humorous guy. I don’t believe he hated me. He hated what I represented- marching in protest against the Amerika he fought in a war to protect. I must have looked like someone else’s son, the way he stared at me with the dark eye of “dis” ownership. I felt Dad did care or was it that he cared about public opinion or both?

After I left home at age 16, the way I reconnected with my dad was by happenstance. We met at a crossroads- we were both trying to find a way to earn a living.

While the rest of my family relocated to California, my dad stayed behind to start a new job in Minneapolis. After his training was completed, he would also transfer to California. Dad got a job through a government program the Division of Vocational Rehabilitation. They hired him to be one of their vocational counselors, which seemed ironic to me. My dad was going to be a counselor?

The last thing my dad did before he left was set me up in a fake school.

In Dad’s senior years he sported a straw hat, short gray beard, and cane. He developed a strange propensity for stopping every woman he met. Thinking he was charming, scared her with an unsolicited intrusion into her space. Dad would smile and say to the women, “Hello, cutie pie,” violating their comfort zones. With a look of terror, they’d roll up their car window or run away. When possible, I would apologize and explain that my dad was trying to be friendly.

I will never forget the trip in his final years when I took him to Crater Lake National Park. When we arrived at the lodge, he fainted to the ground. With the help of park rangers, I carried him to our room where he slept for the next 24 hours.

There was no medical help there and my dad suffered Parkinson’s disease. So, if this was his last moment on Earth. Better it happened with me. At this ancient. Spiritual site. Beneath the shadow of a giant, legendary volcanic lake, where the gods did their battles. It was representative of our life together. Some of the things he told me on that trip were so profound and poetic, as though the words came from an unknown man. Indeed, from a man of dual lives.

“I’m glad you got somewhere with your music. I hope you write a book, too,” Dad said on the road. I drove on.

“I appreciate letting me stay at your house and use your car to help with my Hollywood career,” I replied.

Was this his end-of-life confession? The inspirational scenery, where everything locked in his heart poured out. I never knew who my dad was. Then he opened up more.

“There is something else, I want to tell you,” Dad said, and then he fidgeted and hesitated.

“Go ahead, I’m listening,” I told him, bemused with his forwardness.

“When I enlisted into the Navy during World War II, I lied about my age. I was one year younger than the legal age, which was 18 years old,” he revealed.

“That’s cool, Dad. A lot of young guys back then did that,” I said.

“While I was at sea, I got a Dear John letter,” he said.

“Who was the letter from?” I asked.

My dad paused, and then exhaled, “I had a wife before I married your mother.”

A line of goosebumps marched up to my arm. What other dark secrets had my dad kept? “All right then, go on Dad, tell me the whole story,” I encouraged him. “Spit it out.”

“Her name will remain a secret, and in the letter, she told me I was going to be a father. I had a son. His name is Steve. He is your half-brother,” Dad said, handing me his photograph. “Until last month, we kept it a secret.”

I looked at the photograph and drove off the road. Steve looked identical to my brother. He had the same hair, build, eyes, and facial features. Steve was three years older than my brother.

“That’s incredible. I have a half-brother? What does he do? Where does he live?” “Steve has a large family, with grandkids, in Medford, Oregon,” Dad said.

“I’d like to meet him,” I said.

“I will and arrange that,” Dad responded while gazing out the window.

“There’s more, isn’t there?” I prodded, “Tell me the rest. It’s now or never.”

“My first wife lives in Los Angeles,” he confessed.

“Okay… go on,” I urged.

“You also have two aunts- one is 99 years old, and the other in her early ’80s. You also have a half-uncle who owns a dental lab in Los Angeles. Another half-uncle owns Hennings Construction in Clearwater, Iowa. My youngest half-brother worked most of his life in Alaska as a gold miner, and died in Florida.”

When does a secret become a double life? I contemplated.

“Dad, what happened to your father? You said he died?”

“I found him in an old folk’s home in Iowa still chasing the nurses,” Dad grinned.

Years after his passing. His third wife revealed that my dad never told her before they married that he had any kids. When I visited he instructed me to say I was his nephew.

The most that we had in common was we sold insurance. He lived and died by the numbers. We’re out of or under-employed most of our life. We moved a lot.

He loved to sing old Frank Sinatra songs and so did I.

As time wore on, my dad relaxed his outlook on life. His hardliner. Prejudicial philosophy softened by a combination of age and Parkinson’s disease. Our disagreements left unanswered questions, but I held no grudges and I hoped he felt the same. I focused on the positive.

On his 81st birthday, he gave his infamous, playful, thumb on the nose- hang loose cheer.

“Tally-ho!”

Released by airplane over the Southern California Coast. 33 degrees and 35 minutes N. Latitude by 117 degrees and 58 minutes W. Longitude. At an altitude of 500 feet, at 10:57 a.m. June 24th, 2005.

About the Creator

Arlo Hennings

Author 2 non-fiction books, music publisher, expat, father, cultural ambassador, PhD, MFA (Creative Writing), B.A.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.