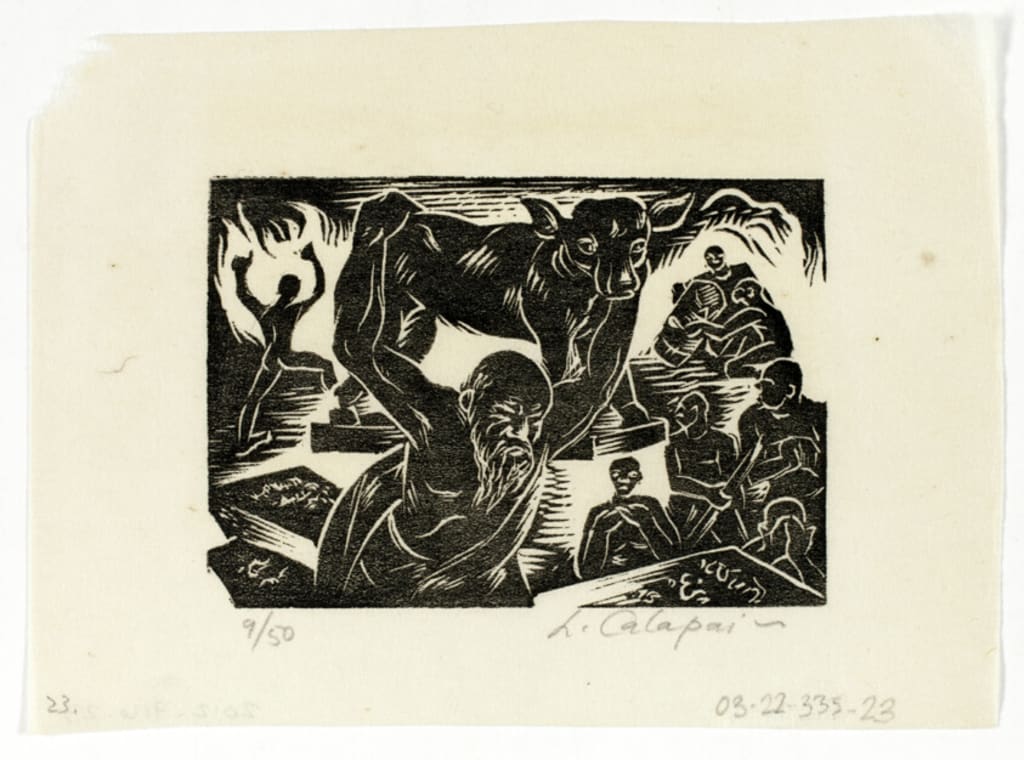

The Golden Bull

It was a bull. Trust me. And it was my idea.

Did you know, nehda, that the golden calf was my idea?

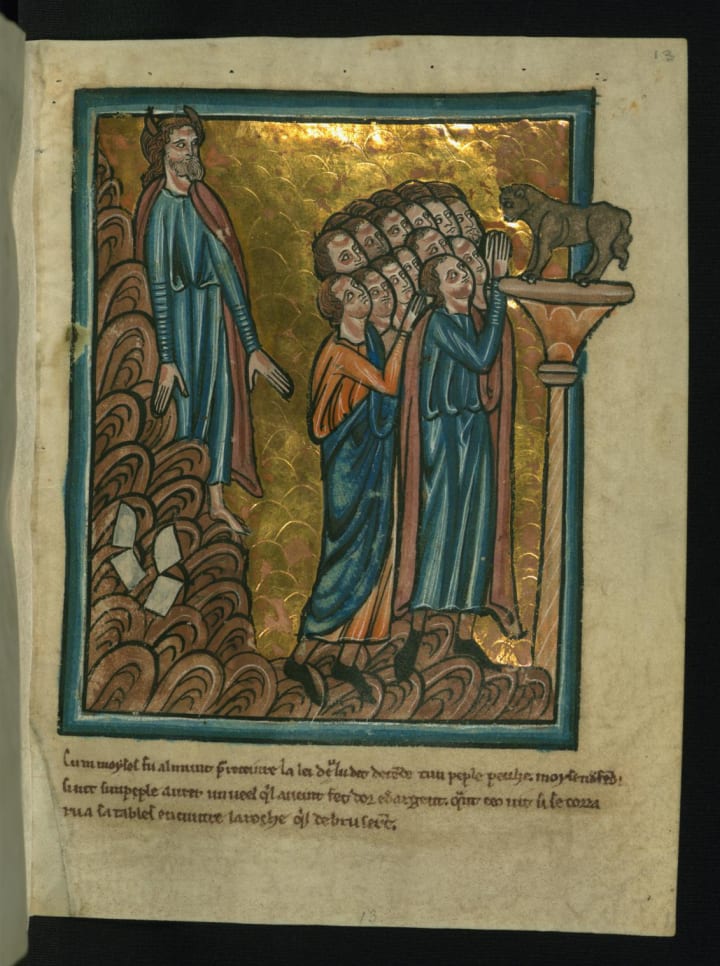

Of course, it wasn’t really a golden calf. It was a raging bull, its nostrils flaring, one foot raised as if about to charge.

Its horns could have pierced flesh, though of course no one got close enough to try.

You’ve only heard of it as a calf, my granddaughter, my nedha, because stories change over the generations.

People wanted it to be something fat and sweet, a symbol of comfort and feasting, of the softness of our people as we waited for the Lord to deliver us from all evil.

But it was a bull. Trust me.

And it was my idea.

See, Moses had been up on the mountain for what felt like ages.

Aaron and Miriam did their best to hold us together, and of course we never stopped praying to the Lord, but in the heat of the day, when all we could see was the blinding sun and all we could hear was the wind over the barren dust of the desert, we only had ourselves.

We were leaderless. We were alone.

Or, at least, we felt as if we were.

And let me tell you, nehda, there is only a very thin veil between feeling alone and being alone.

It wasn’t solid gold, either. They’ll tell you that we melted down all the jewelry in camp, but really, how much gold do you think we had? A people fleeing slavery, after centuries of bondage, baking flat bread as we went - it was no glittering bazaar.

So we carved it out of soft desert limestone, and where there were folks willing to hand over their tarnished old bangles, we pounded them flat and laid the thin gold leaf over its surface.

When it gleamed, you could hardly tell the difference.

Who carved it? Well, it was me, your old Bubbie, and a few other young women, our fingers thin and nimble, our lungs still healthy enough to be unbothered by the clinging white dust our work constantly threw off in gritty plumes.

Why me? Because I’d seen a great raging bull once before.

And because it was my idea.

One day, long ago, before Moses and the plagues and the great exodus, when I was just a Hebrew girl in a hut helping my mother haul water from the well, I had gone on a walk.

A very long walk.

You see, it was just after the Ten Holy Days of Repentance. The week after, you know how everything goes quiet. Everyone needs a break from atoning, and we all take some space to rest, to slip quiet and unnoticed back into the new sins of the new year.

So instead of being at home to help my mother, I went on a walk. I passed Haifa street, and Yehuda, and I walked through the Hebrew village square, and through the Zebedee family fields.

All of these are places you will never know, nehda, because they were in Egypt, and you were born on the other side of the sea, after the parting, after the forty years of wandering. But for me, as a girl, this was my whole world.

I walked, and I walked, and when I was far enough past the village, I took my hair down and let it fall over my shoulders, tossing it like a wild animal.

I felt free. I wasn’t, of course - it would still be a long while before the Lord rained down frogs and fleas and Pharaoh lost his boy - but there is a very fine veil between being free and feeling free.

I had new shoes for the new year, and I walked farther, out where I had never been before, where I didn’t know the shepherds by name and their sheep eyed me with suspicion rather than sleepy welcome.

And then I saw it.

A great black bull. It was far off, but I could see the shine of its onyx fur, the long shadow of its muscled shape on the rocky desert ground.

I crept closer, wanting to see such a powerful animal up close. We Hebrews did not have bulls or oxen, we kept sheep. We were supposed to be like them - herd animals, docile and gentle.

Egypt would not have us learn anything from the bulls.

As I walked toward it, the bull sensed me. He lifted his head and I saw his eyes, flashing nearly white in the morning sun, glaring at me with the intensity of a creature who knows that he belongs on the land where he stands.

And stand he did, nehda. His hooves were as big around as my face, hard and grooved. He tapped the ground with one of them, and I stopped right where I stood.

It was only me and the bull.

He lowered his head, pointing his horns straight at me while keeping his stony gaze trained on my face.

I looked back at him. I saw power. I saw fear. I saw freedom. I saw loneliness.

I saw a bull.

I saw myself, a tiny Hebrew girl reflected in the glisten of his unblinking eyes.

I backed up, and he continued staring, but he did not move.

Was I frightened? Maybe, nehda. Or maybe I was simply smart enough to see the risk of it all. Is it fright, or simply good sense, that sends our people scattering away from that which would destroy us? When does intelligence become fear? In the face of a raging bull, perhaps.

Either way, I left the field, and I made my way back toward the village, where the sheep knew me and where I had plenty of water to haul before the sun reached its peak in the sky.

I pinned my hair back up, and it sat heavy on my head. But instead of feeling weighed down, as I did so often, I felt as if, perhaps, I had horns.

So it was that morning, a quiet day in the middle of the month of Tishrei, that I remembered all those years later, in the camp at the bottom of the mountain, when Moses had gone and not yet returned.

I began to carve the bull, simply because I could see him in my mind’s eye. I knew how the nose should look mid-snort, how his thick leg should be holding just one massive hoof off the ground in a gesture of confident threat.

And then others joined me, and soon we had created an image, one of strength, of anger, of solitude, of the poised moment just before a rush into something new and wild.

We didn’t plan to worship it, nehda. But we loved it all the same.

Our bull. Our sharp horns, our muscled flanks, our hot breath, our simmering rage, our shadow cast in an empty field.

Ours.

And when I looked at its golden surface, I saw my body reflected in the curved shine of its golden shape.

I saw power. I saw fear. I saw freedom. I saw loneliness.

I saw a bull.

I saw myself.

About the Creator

Lacey Doddrow

hedonist, storyteller, solicited advice giver, desert dweller

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.