The End of Malcolm McLeod

Solstice, leer, horseshoe

Some stories beg to be told like plaintive children, desperate to be heard in a noisy world. Others, like the story of poor Malcolm McLeod, my brother, demand to be told; they bite and scratch up the throat, making no allowances for fear. So listen, young men, and take heed, for I'll tell it only once. This story could save your life when you walk the misty moors of Scotland.

In the summer of 1566, there was much to celebrate. The sun rose high and gold above the fields and coast, and two days after the birth of Prince James, the solstice whispered across the land like the breath of Cailleach herself. We gathered, the whole village, to say goodbye to the summer and welcome in the long, watchful nights of winter with feast and song and dance, for there was more surity, then; no more a land under a foreign Queen with no heirs. Mary had given us James, and the summer had given us joy.

It was an ungodly celebration; that's what the Kirk said when we brought his body home. An ungodly celebration, steeped in heathen tradition, and his death was the price. But you tell me, what God does not love joy? Or laughter? Or celebration? What is ungodly about being thankful for the fruits of the earth?

While the women sang and dance and the children gathered wild fruits and herbs, the men built a mighty fire... and, of course stopped to stare. Or leer, in some cases, at the girls as they passed.

Malcolm was my brother, and a good boy; just seventeen, he had a girl in mind to marry. But like most young men, his hea hard to pin in place. Mary Gillespie was pretty and friendly, with bright green eyes and red-hair as bright as his own.

I would have married her myself, but she wanted him, for her sins, and he, by turns, wanted her, and Sarah Ritchie, and Mhairi Bell... and any other girl who would smile at him.

That was what they fought about; while she danced and played with her sisters, cooked and cleaned with her mother, he was watching Mhairi Bell with a gleam in his eye and no shame while she smiled and batted her lashes.

"I'm just looking," he said to me with a petulant, little boy pout, "don't be grim, David, I'm only looking. Can't a man do that?"

"A man can do that, but he has to take his lumps when he's caught," I replied with shameful glee, because he had been caught. You see, some said Mary was a witch, and her mother, too, but who could be sure? All we knew was that they could set bones, stitch wounds, and coax difficult babies from their mothers, awash with blood but living and screaming. I saw the thunder on her face long before she slammed the pot down and marched across the space between them, and I admit I wanted to see him humbled.

Most of the young men did.

Malcolm was fiery and funny, handsome and quick, and though he liked women too much... well, they liked him too. Mary was quicker, though, sharper, and more dangerous. Mhairi Bell disappeared from sight like a scalded cat, her smile wiped away like grease from a pan.

"Mary, I was just looking," he raised his hands in mock surrender,

"Look all you like," she whispered, "but you'll do right by me, Malcolm McLeod, or by none." She pointed one sharp finger, and if he felt the shiver that went through us all under that hot sun, he never let on. He just shook his head and repeated,

"I was only looking." This time with a laugh. I've wondered often if that laugh was the final nail in his coffin, for after Mary stamped her foot and turned on her heel, she spat once on the ground and left.

We never saw her, or her mother, again.

Truth is, they were a bigger loss to the village than Malcolm, though people preteneded to be pleased. They were witches, we agreed, or murderesses, at least, but when the bones didn't set right and the mothers bled dry... well, more than one set of eyes turned to the old Gillis croft and wished there was a light on in the window.

"She'll be back," he said, teeth flashing in the sunlight, and the men laghed. But when the bonfired burned low and the sun had dipped beneath the distant treeline, he looked like a little boy again. "She will come bacl, won't she?" He asked, and I could only shrug.

"You tell me," I said and passed him the bottle, hoping it would stop his whining. We should have returned home. We should have went to bed, like all the others. The old men and women, the married couples, the single women, the children. Even th oyther young men fled the night, knowing that the Fair Folk, and all manner of Síth creatures love the dance at midsummer.

Instead we drank while the embers burned down, and he whispered into the merciless night,

"I wish there was a woman here to talk to."

"Blessed Christ don't say that," I said, stricken by bone-deep fear, for all sensible Scotsmen know that what you wish for in the night bears rotten fruit without the protection of the Lord. But it was too late. As if summoned, she appeared; tall and slim with long, dark hair and a rich, green dress the colour of fertile fields. She was laughing, though no-one had told a joke in hours.

She was dancing, though the music had stopped. She seemed, for all the world, like a drunk woman. Though I wondered if she was pretending to be drunk. Malcolm grinned and stood,

"See," he said, "at least God still loves me."

"Who says God sent her," I muttered and stayed in my seat. Her cool, dark eyes passed over me to fix on him, which was not uncommon, I admit, but she was delighted, ecstatic, to see him.

"Are you lost, lady?" He asked, pretending to be a gentleman,

"Who can be lost in their own land?" She asked and shook her head, "I'm exactly where I need to be."

"Drink with us?" Malcolm held out his hand to her, and when she flashed her teeth at him, I fel a cold hand on my back, heard something whisper, 'No'.

"That's not a good idea, Mal," I said, and a spasm passed across her face as he looked away. Like a hand had smeared her features, showing something ugly beneath, "mam and dad will be waiting on us."

"Shut up, David," he frowned shook his head, "go home if you're tired. We'll drink, won't we...." and he stopped, as if remembering she was a stranger and he had never known her name,

"Meb," she said, "my friends call me Meb. We're friends aren't we?"

"No," I said,

"Of course," Malcolm grinned, "Meb." He rolled the name around his mouth as if tasting it.

"No wonder Mary left you." If he heard my parting remark, he didn't turn to acknowledge it.

I tried to leave, I admit it. Though he was my brother, he made me sick at times. It wasn't his fault Mary never wanted me, but it galled to see a fine woman waste herself on a foolish boy. She could have had anyone. She chose him. And so I left, but that cold hand was on my back every step of the way, and Meb's laughter chased me to the edge of the market, making the dark road ahead seem like a nightmare. Tall trees and swaying grass hissed and whispered. The road seemed to go on forever, and though there was a candle in the distance, burning outside the door for us, no doubt, it looked like the road to purgatory.

'No'.

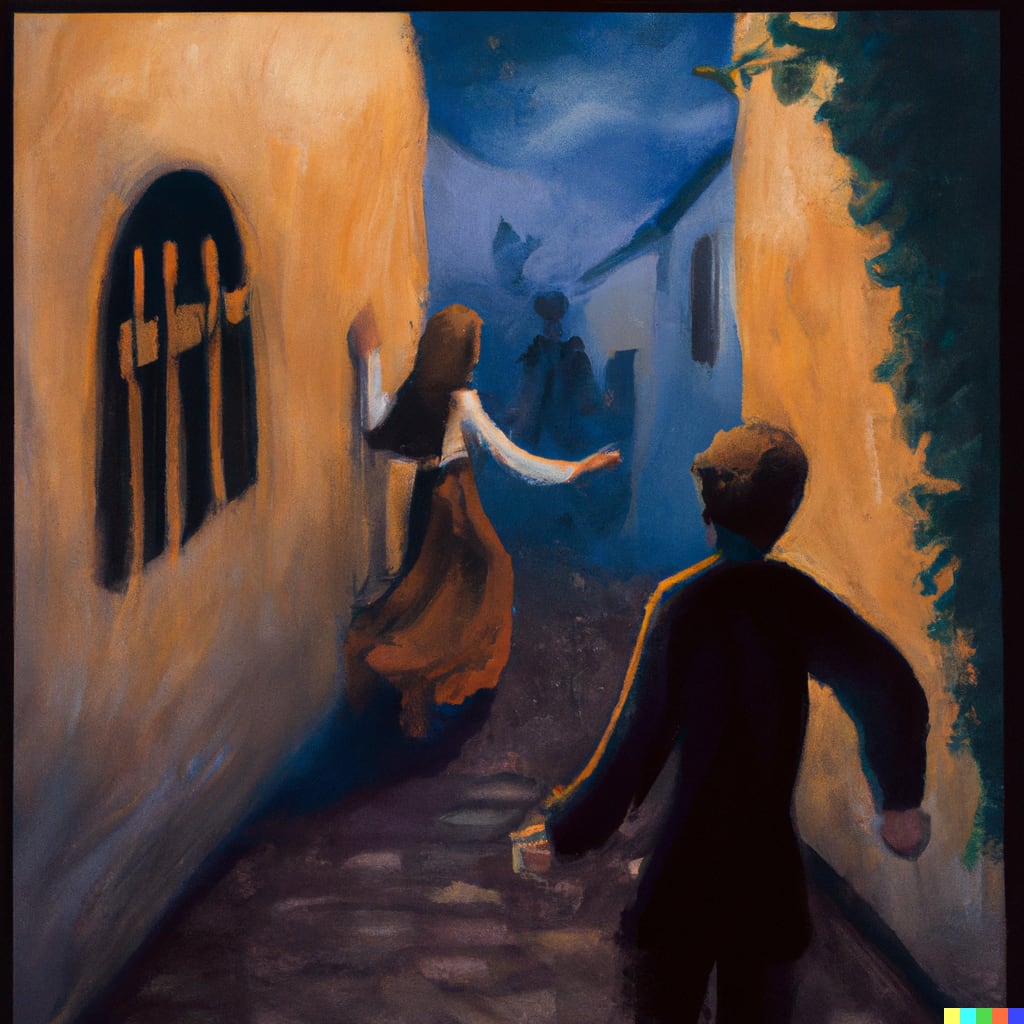

I heared it this time, as clear as you hear me now, and I turned back. Only the market was empty when I arrived; only the remains of the bonfire cracked and smoked. But a shadow passed around the corner on its far side,

"Malcom?" I asked and stooped to pull the edge of a smoulder ing stick from its heart, blowing hard to make the embers reignite. In the light of that weak flame, I followed the shadow, and saw him, following her as if charmed. As if sleep walking, "Malcolm!" I called out for him again, but only Meb seemed to hear, and though her face was blurred by the gloom her smile was terrible.

Eyes like coals and bleached bone teeth, it was a death mask that slipped slowly around the corner of the stables as the few horses reared and screamed. He followed without hesitation, and left me alone once again... but I did not feel alone.

Every hair stood on end as if there was lightning on its way. AS if a cold winter wind had whipped between the wattle and daub buildings to bring ill-tidings.

Now it was I who walked in a trance, aware of every whisper in the air. Weighed down by a terrible dread as the corner of the stable neared and the horses were terribly still. As the weak torchlight spilled into their stalls, their eyes were wide and white with fear, their ears pinned back. A guard dog cowered under a flighty mare, risking trampling rather than be left on the other side of the fence.

It was relief, I felt, when I saw Malcolm's broad form under the tree, though Meb's arms were tight about him. A tryst, nothing more, and a dishonourable act, but hardly his first. Mary Gillis was right to be rid of him, I thought and shook my head as I backed away, tripping over a bucket. The mightly clamour it caused sent the horses into frenzy again, and the dog, poor beast, yelped, but did not leap free of the stable.

He fell, and at first I took it for shock and drunkenness, but Meb stayed upright and he never moved again.

The beauty was gone; I saw for the first time what was underneath the mask. Madness, terrible madness; not a madwoman, you understand, but something else. The bright black, glittering malice of a rabid vixen. Or a creature that has seen too much time. Blood-slicked from chin to breast, she leapt - leapt like a great cat, showing the bent goats legs beneath her dress, and I scrabbled in the dirt, swinging the first thing my hand fell upon.

If God had any part of that night it was this, for I swung an iron horseshoe with all my might. Where it struck, Meb turned grey, her face seeming to collapse in on itself as she reeled and screamed into the darkness beyond my torchlight before cirlcing back too late.

I spent the last dregs of that night in the stable stall with that flighty mare, curled around the shaking, injured dog who had known better than me all along. You see Baobhan Síth may be less elegant than the rest of the fair folk, but they are still kin.

The cold iron of the horses shoes and farriers tools were all that saved us. In her fury, she raged around the stable, screeching and cursing in some forgotten tongue... but she never breeched the perimeter. Never set one dainty hooved foot over the stable threshold. And when she knew she had lost, she crouched beside the outer wall and stared with one glittering eye through the gap in the planks at me and the cowering dog.

Stared until dawn. No longer beautiful, even her ragged breaths smelled of rotting flesh, she stared and stared, the un-natural wide curve of her mouth showing flashes of white teeth until with a sudden stiffening of her back, she fled and let the sunlight take her place.

The farrier found him first, then I, lying in the field with his legs bare, his throat torn, and her belly opened. They say it was the lack of blood on me that told them I was innnocent, but in truth I think it was the way I stared. Stared at the gap between those planks until they wrestled the dog from me and dragged me to my fet, still clutching the scorched horshoe like it was a holy cross.

An ungodly celebration, the priest at the Kirk said with a shake of his shaggy grey head. An ungodly celebration and an ungodly end for Malcolm McLeod. He could not be buried in the Kirk yard, he said... but he still took tithes at the funeral.

About the Creator

S. A. Crawford

Writer, reader, life-long student - being brave and finally taking the plunge by publishing some articles and fiction pieces.

Comments (1)

As soon as he uttered the wish, I knew exactly what was coming for him! Poor man, but he should have known! I absolutely LOVED this story, brilliant work.