SIR ROBERT HENRY AND THE ROSE

A story of murder, friendship, family and love

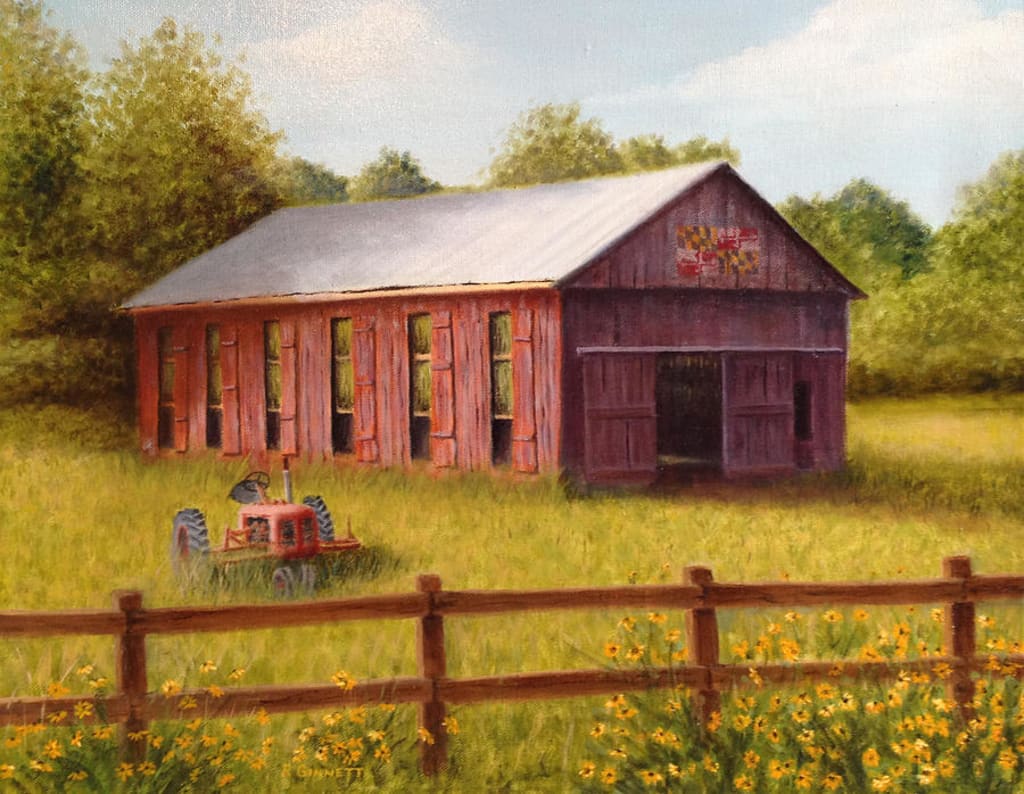

I used to love the way the scent of the old barn spilled out onto the field in front of our home. The tobacco leaves dryin’ from the wooden beams like fresh earth was cast out on the open breeze in some triumphant wake. Like fresh cut grass in the mornin’ when the dew is still settlin’ and hasn’t yet been tamed by the sun. It made me happy.

My Daddy was a tobacco farmer. Like his Daddy before him. And most families in Betterton. But after Reconstruction, the tobacco trade was harder. Seemed like everyone was strugglin’ during those years to put food on the table and keep their plantations workin’.

Momma thought we should turn to plantin’ apples and plum trees, but Daddy didn’t love workin’ in the field anyway. Momma loved gardening. But she loved roses best. Red ones, yellow ones, pink ones. She said that if heaven had a scent, it would surely smell like roses. My Daddy loved my Momma’s garden, but if he could do anything in life it would be to captain a steamship. After the War ended, Betterton became a favorite stop for northerners coming down the Delaware through Chesapeake Bay.

I liked it better when I was a young girl before the turn of the century. Before we became a pleasure stop. But it was good for Betterton families, that was the honest truth, and my Momma found good work in the old mill restaurant and dance hall along the beach after my Daddy died.

The Sassafras river spilled out into the Bay along the rocky shore and sandy beach where Minnie and I used to play mermaids and pirates. We were only 12, but we knew that mermaids could lure pirates with their charms. I would braid my long, dirty blonde hair with seaweed strands cascading down my back like a salty wedding train and strut down the beach singing:

A sweet Tuxedo girl you see ; A queen of swell society

Fond of fun as fond can be ; When it's on the strict Q.T.

I'm not too young, I'm not too old ; Not too timid, not too bold

Just the kind you'd like to hold ; Just the kind for sport I'm told

Ta-ra-ra Boom-de-re!

My Daddy had brought home the recording on his trip back from Boston. Momma and he would play it on the phonograph and laugh and dance on our creaky porch overlookin’ the old tobacco barn. I didn’t know there were naughty words in there but only liked how it sounded in the air along the seashore. It sounded like a good mermaid song. And Minnie and I would surely make the pirates swoon if they could only hear us sing it. The fisherman that crowded the pier would laugh and cry out to us to stop frightenin’ the crabs as they brought in their nets and traps.

Minnie said she couldn’t be a mermaid because she didn’t have golden hair like mine. “There were no negro mermaids,” she said. But I knew that was foolish talk and told her that the ocean was full of black fish and orange fish and red fish and yellow fish and every color, and mermaids were no different. She was my best friend.

Betterton was a small town. We knew just about everyone. And the negro families were always welcome in our church and our home. Momma and Daddy said, “God spoke his word and his word be true for we were all baptized by one Spirit so as to form one body - slave or free.”

Minnie was with me the day I met Sir Robert Henry for the first time.

It was a cool Autumn day and the trees were on fire, throwin’ red and gold leaves into the wind and rainin’ sparks down upon us as nature’s show. Minnie and I loved to collect the leaves and see who could find the brightest ones.

Daddy was clearin’ the dried tobacco leaves from the rafters and makin’ a pile on the southside of the barn when he called out to us, “Rose! Minnie! Come quick and see what I found.”

“What is it? What is it, Daddy?,” I exclaimed as I ran toward the open barn doors. The musty sweet smell of dried tobacco enveloped me as I approached the southside of the barn. Minnie followed close behind.

“Look there, in the rafters, in the corner, down low. Do you see him?”

My eyes adjusted to the dark peering through the dusty air. At first, nothing. I saw only old wood and rusty nails.

And, then, I saw it. I saw its talons first. A stray board had split creating the perfect perch in the corner for nestin’, a natural shelf for the warm pile of hay, twigs and tobacco leaves. I approached cautiously and slowly. And then I saw his face as white as snow. His eyes were like shiny, black marbles. His beak buried in a sea of snowy feathers, his face at first expressionless, but then finishin’ with a wise smile that only owls can make.

“Looks like we have a houseguest, Rose,” said Daddy. “It’s a barn owl and he looks quite comfortable there.”

“I’ve never seen a real owl ever before,” said Minnie.

“It’s good luck to have a barn owl come and stay with you,” said Daddy. “This one’s a boy owl. You can tell because the girls are much prettier.”

Minnie and I laughed.

“See if a barn owl comes to roost and make himself a home, that doesn’t mean everything’s going to be alright,” said Daddy. “No ma’am, an owl is tellin’ ya something. Like somethin’ needs to change. Or somethin’ will change. The owl knows, yes he does, that change can be a God awful thing sometimes, but sometimes we need to wake up different. Or just have the courage to wake up at all. Everything good in life comes from change. And everything bad in life comes from change. The trick is to know the difference and then know what do with it.”

My Daddy continued to speak, but his voice became softer, calmer.

“The Indians talk about the owl as a messenger – a spirit guide for souls that have one more thing to say in life. So sometimes when an owl comes to stay with you, you only need to listen. But not with your ears. Now close your eyes, girls. Rose, close your eyes, now.”

My Daddy put his hand over my eyes and called on me to close them. I didn’t want to but I did just the same. Minnie always listened to my Daddy.

“Now, listen,” he whispered. “Listen to your heartbeat, hear the rustling of the leaves and now picture the owl and his wise, kind eyes.”

I could see in my head the perfect heart-shaped puffy white face. His wings freckled like the rocky sand of Betterton beach. Golden, salt and brown sugar wings. Soft, yet powerful. He only stood 12 inches tall maybe, but to me he was the biggest bird I’d ever seen.

And then he screeched – softly, as if in approval of our presence. We both giggled with anticipation. But we didn’t dare open our eyes.

“See! He’s talking to you,” Daddy exclaimed. “Remember, girls. Our time here on this earth is worthy. Worthy of good things. Of better things. Don’t be afraid to close your eyes and listen with your heart. Don’t run away from change. And if a barn owl visits you, take the time to hear his wisdom.”

I opened my eyes. I couldn’t stand not to see him. And I could see the wisdom in his face, like Daddy said. As if he carried more inside him. I could see his soul.

“We need to give him a name,” I said assuredly. “He deserves a good name.”

Minnie shouted out, “He’s Snowball! His face is a big snowball.” She was very proud of herself.

“No, Minnie. That’s just not serious enough a name for such a distinguished visitor.” I didn’t really know what distinguished meant, but it sounded like the right thing to say. “He is a gentleman.”

“Like a king?” asked Minnie.

“No, more like a prince,” I argued. “Or nobleman. Sir. Sir Robert. Sir Robert Henry. Yes, that sounds just fine.”

“I like it,” said Minnie. And we bowed and curtsied before him.

“Now, Rose, you and Minnie run along to the house and get yourself some supper. It will be night soon and this Sir Robert Henry is going to have to go hunting. Minnie, you can stay the night if you get your Mammie’s blessing.” We ran to the house and couldn’t wait to tell Momma about our new prince.

That was the last night I saw my Daddy alive.

But he would speak to me again.

I didn’t like my Uncle John much. He wasn’t like my Daddy at all. He always smelled funny, like the men downtown that stumbled home to their wives and girlfriends. And he always was on my Momma about chores and such. But after they found my Daddy shot dead in front of the AME church, my Momma and I needed help. And my Uncle was alone and willin’ to come and help with the crops and till the fields.

He was Daddy’s little brother, but he didn’t look so young. No, he looked like an old man still. But I think it was his heart that made him look old, not his years. He didn’t like the negro families in town. Especially the families that my Daddy used to help. You see, my Daddy was good with his hands and he wanted to help the families build their own church to worship God and such. They built a beautiful church down on Main Street just a few blocks West of the beach. Momma, Daddy and I used to go and sit with Minnie’s family.

My, my they could sing! I had to sometimes put my hands over my ears to think. But her Mammie had a beautiful voice and you could hear her sing above everyone else, as if she was singing to the angels themselves.

Go tell it on the mountain, over the hills and everywhere;

go tell it on the mountain, that Jesus Christ is born.

They found my Daddy just below the steps of the church in the overgrown grass underneath the great swamp oak tree on a bed of fallen chestnuts.

It was the day after we met Sir Robert Henry. My Daddy had gone to the church because there were some people there yellin’ or somethin’. He was always trying to make the peace. Momma didn’t want him to go, but we ate our supper and told Momma all about Sir Robert Henry. Minnie and I and couldn’t stop talkin’.

It was very late that night when Minnie’s older brother came to knockin’ on our door and tellin’ my Momma that Daddy was dead. I remember that night like it was a dream. So full of magic and wonder as the moonlight shown through my bedroom window and cast shadows of mermaids and pirate ships on my wall. I imagined Sir Robert Henry on the hunt for mice as he flew through the moonlit fields of Betterton searching for his bounty to feed his family.

My Momma screamed. It wasn’t just any scream. I had heard her scream before. This wasn’t a happy scream and it wasn’t the scream I heard when that mouse found its way across our kitchen floor to the basement. No, this scream was different. It was as if all the life just got screamed out of her at once.

No one could say who shot my Daddy. But Uncle John thought for sure it was one of the negro men in town that was unhappy about the drop in tobacco prices. Many of the field laborers were out of work. And there were tensions buildin’ between the men in town that needed to take care to feed their families. It’s funny what a man will do to feed his family. When hunger and despair creep in and men are faced with change. And fear overcomes faith.

They didn’t find the gun that killed my Daddy. But I would learn much later in my 20’s that they did find the shot that put three holes in his heart. They were .55 caliber bullets from a smooth bore barrel. A most unusual firearm. There were only 2,900 of them produced over in Europe after being invented during the War in New Orleans. About 900 of these revolvers were shipped to Confederate soldiers. It was called the Lemat revolver after the man who made it. The 9-shot cylinder revolved around a separate barrel that could fire like a shotgun by flipping a lever sending out a stream of buckshot. It made killin’ easy.

I was 15 when I saw Sir Robert Henry again. This time I was alone. I wasn’t allowed to play with Minnie anymore. My Uncle John didn’t believe that we should “mix company.” I never understood what he meant by that. We stopped going to the AME church and started worshipping at the white church in Still Pond up the road. I didn’t like it much, but mostly I missed Minnie.

We were still livin’ on the plantation and the barn was still standin’. But the sweet smell of tobacco leaves dryin’ in the warm barn were all but gone. The barn was nothin’ more than a monument to the past, a symbol of my Uncle’s idleness. There were still some old harvestin’ tools and an old steamer trunk in the corner that Uncle John brought from the city when he moved in. Cobwebs hung from the rafters like curtains in a haunted house.

But there he was. Sir Robert Henry, perched in the corner, his feathers pulled back as if he were standin’ at attention. His white ghostly feathers fanned out over his regal face. His eyes looked deeply into mine as I approached.

“Well, hello there, Sir. We have missed you. But I’m happy to see you have come back to your kingdom to roost.”

I came closer. He seemed smaller to me now and at first I thought, perhaps, this is not Sir Robert Henry, at all.

It was dark, but the rays from the early evenin’ sunset shone through the barn like lighthouse beacons guiding lost sailors back from the sea. He was in a slightly different roost, a little higher where he could get a better view of the barn floor below and any feast he might spy scurryin’ across the bands of sunlight.

It was then that I saw his talons, resting on the edge of a rotted beam of wood. There was no nest but only him. At first, I didn’t see the rose, gripped between his talons. But as the sun slowly set, I could see clearly now as a beam of light was cast upon him.

It was red. But not just any red. It was unlike any other red I had ever seen. As red as the skin of the ripest, sweetest apple, but bright like the sunrise over Chesapeake Bay. It was not full, but young. A bud just beginning to bloom as if moving from adolescence to adulthood, growing up beautiful in a wasteland of cobwebs and dead tobacco leaves.

“Sir Robert Henry, is that for me? You shouldn’t have.” I bowed and curtsied before my prince.

Holding on to the rose, the owl spread his wings in a majestic show as if pleased by my reverence. His wings stretched at least three feet, his head held high and his white breast, powerful but kind, puffed up as if to say, “Look at me. I am not afraid.”

The rose fell. Not by accident, but deliberately, upon Uncle John’s old leather steamer trunk. It hit the trunk shedding some of its petals on impact as they spread across the surface of the trunk and onto the dirt floor. The trunk had been there for three years since Uncle John moved in with us after my Daddy’s murder. It sat untouched it seemed. Forgotten. Lost.

Sir Robert Henry looked at me. His wings at his side now. He eyes intent on speakin’ to me.

I remembered the first day we met. When my Daddy told me to close my eyes and listen. I shut my eyes tight.

I could here my heart beat. I could feel my Daddy’s hand at my side guiding me to listen. I could feel the warm breeze blowin’ through the barn and smell the sweet, earthy smell of fresh tobacco leaves dryin’ in the rafters. I could hear the mermaids singin’ their song to sailors. I could see Minnie’s smile and feel the touch of her hand in mine as we gathered leaves of fire in the Autumn air. And, then, I could hear my Daddy’s voice, “Everything good in life comes from change. And everything bad in life comes from change. The trick is to know the difference and then know what do with it.”

I opened my eyes.

There before me was the broken rose. Cast down upon my Uncle’s trunk. Sir Robert Henry sat confidently on his perch. I knelt down before the trunk.

The straps were heavy leather and worn thin. The buckles were a tarnished brass having sat for years unkept. The buckles were all but broken. I took the rose from the trunk and held it. It was from my Momma’s garden. That was for sure. I raised the bud to my nose. It was the sweetest smell. And I could feel the rosebud fill my lungs as if to give me courage and strength.

I pulled back the straps. The brass buckles echoed through the barn when snapped open.

Inside the trunk were simple things. A grey nightshirt and field workers clothing. Old papers and printed parchment. A pair of boots and a box of round buckshot.

Tucked below the nightshirt underneath a quilt, was a small, but heavy pistol. It was a Lemat, double-barreled revolver, only a few hundred produced for the Confederate army, lying at the bottom of Uncle John’s trunk.

My Uncle John was arrested for the murder of my Daddy and sentenced to life in prison up near Philadelphia.

It was hard on Momma and me to be alone at first, but after the steamships started to come through the Bay and Betterton became a hot spot for the rich city folk, we got along just fine. I’m not sayin’ Momma was happy, but we were better just the two of us.

I live in Baltimore now with my husband and my two daughters. I try to get together with Minnie and her family still, but not as often as I would like. But when we do our children laugh at us when we get to sippin’ the wine and singin’ old mermaid songs.

I never did see Sir Robert Henry again. My Momma sold the plantation and the barn was torn down to make room for a theater for motion pictures and such. I go back sometimes and walk along the beach letting my sandals drift over the rocky, sandy soil. The golden sand and chocolate pebbles reminiscent of those glorious wings outstretched as if to embrace me and assure me I was safe.

I remember what my Daddy told me. What the Indians said. That owls are merely a spirit guide for the souls that have one more thing to say in life. And you only need to listen with your heart.

Rest in peace, Daddy.

About the Creator

Richard J. Phillips

I have been a public relations executive, a screenwriter, a politician, a teacher, a restaurant owner and a consultant to NASA's human space program. Life is not supposed to be safe. It is meant to be lived. Make life extraordinary.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.