Names in a Hat

Inspired by teenager Maria Lewis’s Civil War escape from enslavement

The white stallion’s muscles moved rhythmically under her. His rumbling hooves stirred up the only breeze blowing across the harvested ground. As the fieldstone wall loomed up, sweat dripped down and burned Lydia’s eyes. She knew the danger of jumping the stone wall but trusted the horse. There was freedom in being airborne, no matter how short lived. Pegasus, neglected since the Colonel’s death two days earlier, hankered for the jump as much as she did. Neither the other enslaved people, busy at work, nor the master’s family crying over the Colonel’s open grave would know. She and Pegasus craved this. They jumped.

As Lydia neck-reined the white stallion back for another go at the wall, a distant hunting horn rasped its warning blare. While waiting back at the stable, Caesar must have seen the funeral party cresting the hill.

“Just once more, Pegasus,” she whispered, her bare feet goading him forward for their final flight.

As Lydia and Pegasus reached the stable door, bandy-legged Caesar ran up, his legs see-sawing with the effort. Caesar snatched Pegasus’ halter.

“You best git them britches off and git back into your dress, girl. You know Miz Thornton don’t ’prove of you wearin’ pants. And now the Colonel’s passed…”

Lydia scurried off to an empty stall where a cotton dress hung from the hay rack. Fifteen now, a few months earlier she’d switched from the short shifts of girlhood to long dresses. Her passage to womanhood signaled by the change in clothing, she soon would be expected to start bearing children. Lydia peeled off the homespun britches she’d found in the ragbag, stuffing them behind some buckets. Hoping she didn’t smell too “horsey” and tying a yellow head cloth over her coppery ringlets, she strode off to the summer kitchen to help.

Set back from Chestnut Grove’s main house, the small summer kitchen buzzed with activity.

“Here, Lydia, take this platter in and put it on the sideboard… and where have you been?” sputtered Aunty Beebee.

Aunty pulled a perfectly browned apple pie out of the oven. Golden juice bubbled up from the vent holes cut in the crust. Wartime shortages could not dampen the Colonel’s funeral meal.

Aunty Beebee pointed to the rough-hewn oak table. There sat a blue and white porcelain platter heaped with buttermilk biscuits slathered with butter. Thin slices of salty ham, cured in the plantation’s own sheds, peeked out of each one. Lydia picked it up. Walking along the flagstone path to the house, she slipped three of the ham biscuits into her pocket. Even with the war, Virginia was bounteous in October.

No noise came from the big stone house. Chestnut Grove was one of the largest plantations in Albemarle County. Colonel Thornton had often bragged about Thomas Jefferson himself riding over from nearby Monticello to sample Chestnut Grove’s hospitality. Matter of fact, “pass along” seeds from Jefferson’s orchard had flourished at Chestnut Grove, producing the Spitzenburg apples in today’s fragrant pie.

From the back of the hall Lydia could see straight through to the front door. One of the enslaved workers had propped it open with a brick in the hope of enticing a breeze into the house. Turning right, she entered the shadowed dining room. A black swag hung along the top of the Thornton family portrait which ruled the room from above the mantle. After Lydia carefully placed the biscuits on the mahogany sideboard, she paused before the oil painting.

In the middle reigned the stern-eyed Colonel, his plump wife Jane to his left, his son Randolph to his right. At his feet, his young daughters Eliza and Abigail, dressed like their mother in pastel satin and lace, lounged with a puppy. And there in the background, balancing a tray with a decanter of wine, stood Lydia’s mother, Sabine. Only fifteen, Sabine, dressed in a saffron yellow gown, lit the painting with her beauty. Her curly hair peeped from a vibrant green and purple head wrap. She was clearly a Thornton, her face a darker version of her half-sisters and brothers. Lydia loved to look at her mother’s face. She thanked God for whatever urge drove the Colonel years ago to include his enslaved child in this family portrait. In the painting, an African cowrie shell dangled from Sabine’s neck. Now, just as the Colonel’s dimple dented Lydia’s chin, the cowrie shell nestled between Lydia’s small breasts.

The Colonel had always been kind to her, almost tender. She would miss his calm presence. Lydia had never known her father. Others enslaved at Chestnut Grove claimed he was Jane Thornton’s brother and had died in a duel. But it made little difference who her father was. Lydia knew, under Virginia law, a mother’s status cast her children’s fortunes. Children of free women were free at birth; babies of enslaved women were born enslaved.

That afternoon, the Colonel’s heirs gathered in the sitting room for the reading of his will. The Thorntons, tired from their trip to the graveyard, stomachs stuffed from the funeral dinner, perched and perspired, awaiting the lawyer Sam Chase. The ladies futilely fanned themselves. Newly widowed Jane stared out the window. Her youngest child, twenty-two-year-old Eliza, held her hand. Jane’s daughter Abigail, with a middle softly thickened by early pregnancy, whispered to her husband, Jeremiah Linville. Jane hoped the Linvilles’ wagon ride on Three Chopt Road hadn’t harmed the baby. Journeying twenty miles by wagon was miserable enough, even when not carrying a child. Jeremiah, to Jane’s mind, lacked consideration as a husband. She particularly disapproved of his imposition of closely spaced pregnancies on Abigail. Surely, he could seek other outlets for his carnal needs. She also worried about her son Randolph. His last letter had placed him near Fredericksburg, fighting the Yankees. Jane prayed every day for his safe return. She shot a sad glance toward Randolph’s wife, Emmaline.

Outside, beneath the sitting room window, Caesar huddled on a bare patch behind the English box hedge. The shiny leaves’ tangy scent filled his secret bower. Caesar, an accomplished eavesdropper, knew the will held his future. The other enslaved men and women were counting on him to share the will’s content. As with most illiterates, he had prodigious memorization skills. The contents of the will would spread fast among Chestnut Grove’s enslaved. Even those rented out to work on Richmond’s defenses would get the news quickly. The Colonel had hinted of future freedom to Caesar more than once. Caesar prayed the Colonel had emancipated him in his will. A wasp, energized by the warm day, lit near Caesar, adding to his anxiety. Inside, with a rattle of papers, Mr. Chase cleared his throat and set to his task.

Caesar’s eyes were squeezed shut in concentration. He wanted to remember every word.

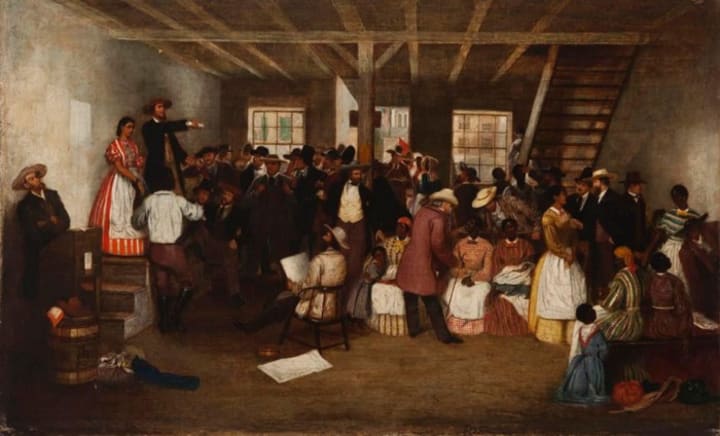

“And as for my slaves, I am directing Samuel Chase to write down the name of each one on a chit of paper. These chits are to be placed in a hat and my heirs are to draw out the number of chits as listed here. Each heir will become the rightful owner of the slaves whose name they draw…”

There would be no emancipation for those men, women and children held in slavery by the Colonel. Caesar wept.

Around midnight, a lone cricket chirped amongst the summer kitchen’s stored provisions. Aunty Beebee sat on a sawed-off log in front of the empty fireplace, her ample silhouette outlined by moonlight, her voice firm and low.

“You got to go, Lydia. You got to go now, tonight. Else Master Linville will take you away to Goochland tomorrow. We talked about th’other day, what we’d do if the Colonel sent us elsewhere. You’re a young girl. You can grab your freedom. A girl lookin’ like you won’t be safe from a master like Jeremiah, especially now Abigail’s with child again. You got to go.”

“What about you and Caesar? I don’t want to go without you. Where will I go up north? How will I live? Can’t I stay here?” pleaded Lydia.

“Caesar and I will be fine. We’re stayin’ here with Master Randolph and Ms. Jane. We’re both too old to go, but you got to go now. Just remember…never trust a white person except maybe a Union soldier, even if they say they want to help you. You may have blue eyes, but you’re still African. Freed Black people will help you. Union soldiers or freed Black people — that’s it. Anyone else, be on guard. We’re not too far from Pennsylvania…” Aunty Beebee went on. “Just keep the big mountains to your left. You should reach those freedmen in Orange tomorrow and after that, you’ll be on the Carolina Road.”4198

Lydia trod gingerly in the grass along the side of the moonlit road leading away from Chestnut Grove. She hoped the trees lining the stone fence rows would hide her. Aunty Beebee’s cloth poke hung from her waist, heavy with food, a little money, and scrounged-up clothes. The dress and shawl in the poke looked more like a white person’s clothing than Lydia’s gaudy dress. She’d change clothes when she got further north. For now, if stopped by a patrol, she’d use her old permission slip. She’d claim she was being rented out to Jane Thornton’s sister to help with the autumn harvest. Further along, once she was north of the large Albemarle plantations, she planned to pass as white. Whispering a little prayer, she picked up her pace.

Hours later, Lydia’s homemade shoes were proving no match for the road’s stones and holes. She was sure she would find a blister if she took her left shoe off, but she didn’t have any time to waste.

“I sorely miss you, Pegasus. Sorely!” she joked to herself. Looking right, the sky was definitely starting to lighten up. In the last little bit of time, the birdsong had changed from an occasional hunting owl’s hoot to the soft calls of mourning doves. Soon the road would beckon to travelers who wanted to avoid the midday heat. She’d been walking the rolling hills all night. She would speed up and walk fast as she could on the downslopes. Next, she would slow down a little on the gentle upslopes to catch her breath. Surely, she must be near Orange. Lydia’s only trip to the little town before this had been when she was twelve. She’d been sent along with Aunty Beebee to help with a wedding. She couldn’t remember the terrain, but according to Aunty, the freed Blacks lived in the southeast quadrant of Orange. The prevailing northwest winds blew the entire town’s chimney smoke toward their little collection of small cottages and cabins, making it the sootiest, cheapest, and least desirable neighborhood.

The creak of a wheel silenced the doves. A dilapidated old wagon was cresting the hill behind her. With no time to hide, Lydia forced herself to keep on walking.

In her mind, she went over her story: “I’m just going to Arrow Wood to help with the harvest. My owner couldn’t spare more than one slave.”

As the wagon drew near, she turned and let her breath out. The driver was Black. The man stopped his wagon beside her and tipped his hat.

“Morning’ Miss. Where you goin’ all by yourself?” “Orange, sir,” Lydia said.

“Well, climb on up. You don’t want to be wanderin’ around by your lonesome. Orange is jest a hill or two more ahead. Who you seein’ in Orange?”

Lydia looked the older man over. There was no smell of alcohol about him. His work clothes were worn, but clean. A smile lit his calm mahogany face. He glanced at her poke.

“I think I know where you belong, Miss. Don’t worry. My name’s Elisha Martin. I’m a free man, a carpenter, livin’ just outside Orange. I’ll git you where you’re headin’.”

Lydia smiled, clambered in and covered herself with the horse blanket and empty feed sacks in the back of the wagon. She must have dozed off as it seemed no time at all before she was furtively hustled into a small log house by an elderly Black woman.

Once in the door, the tiny-boned lady introduced herself as “Miz Smith” and shooed her up a wooden ladder. Broken chairs, ratty baskets, a broom, and sacks of provisions were strewn about. In one corner of the attic, a large wooden chest partially blocked a window. Following the old woman, Lydia saw a pile of old clothes on the floor snugged between the chest and window. Finger to lips, Miz Smith pantomimed to Lydia to rest on the pile and go to sleep. Lydia was only too glad to get off her aching feet.

She slept through the day at Miz Smith’s cabin, tucked up under the eaves, out of sight. Lydia woke up in the gloaming. The aroma of frying chicken filled her nose and made her stomach gurgle.

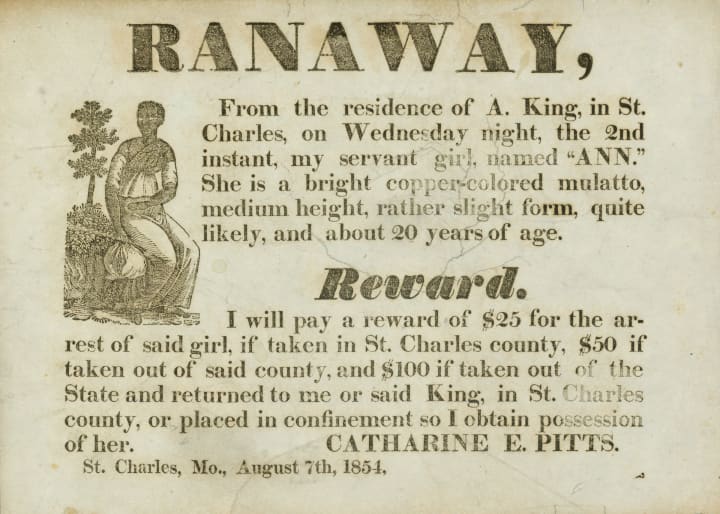

With a crash, the weight came down on her. She wasn’t on her way to help another plantation owner with his harvest. She was illegally fleeing slavery, according to the law. By now, Jeremiah Linville had certainly figured out she had fled. He might be in Charlottesville right this minute putting a notice in the newspaper with a reward for her return. If she were caught, she’d certainly be beaten at the very least and maybe worse. She may have feared he’d treat her poorly before now. By running away, she’d guaranteed punishment if she were ever caught. Lydia took a gulp, sent up a prayer for protection, and edged over to where the ladder poked into the attic. Down below, Miz Smith hummed a hymn as she stirred up cornmeal batter. A pot of greens bubbled on the wood stove right beside an iron skillet of frying chicken. Miz Smith looked up at Lydia. She put a finger to her lips, cutting off any conversation for now, a wide grin splitting her diamond-shaped face. A palm out hand let Lydia know she needed to stay upstairs.

Once full darkness fell, the light from downstairs changed. Miz Smith had lit a lantern and pulled shut the flour sack curtains.

Only then did she whisper up to Lydia, “Supper.”

Lydia clambered down the narrow ladder, bringing her poke with her. Over the tasty meal of chicken, cornbread and seasoned greens, the two chattered like old friends. Miz Smith had scrimped and saved and bought her freedom years ago, marrying a freedman, Jonas Smith. Now, she was a widow. She supported herself scrubbing laundry and sewing. Miz Smith had two grown sons in town and three grandchildren. She kept busy with her work, but things were hard with the war. Still, she made out okay and considered herself fortunate. Lydia was safe in this part of town, but Miz Smith still liked to be cautious. She’d put up others fleeing slavery and wanted to be able to keep on doing so. Lydia helped her clear the table and wash the chipped dishes.

“The next part of the trip will be both easier and harder,” opined Miz Smith. “Easier because the road’s flat, but harder because there’s not many freedmen to help you. You’ll be on your own till you get to the Quakers in Loudoun County. You can trust them. You look like a strong girl and I know God will keep you. Just find a good hiding place during the day to sleep.”

“But my aunty said not to trust any white people getting north except Army men. Aren’t Quakers white?” said Lydia.

“You can trust the ones on Goose Creek. No one else. Tomorrow you should reach Culpeper. After Culpeper, you’ll need to change your clothes and try to pass as white. You’ll be too far from Albemarle County for anyone to believe you’re being rented out,” answered Miz Smith.

Miz Smith stuffed Lydia’s poke with apples, cornbread dodgers. and fried chicken wrapped in greased paper. It was midnight. The air held the crispness only felt in the fall. A horse snorted and rattled its harness outside the cabin. With a hug and a kiss for Lydia, Miz Smith opened her back door to reveal Elisha Martin sitting atop his wagon.

“I can give you a head start, Miss. Just crawl back under the blanket like you did this morning. I’ll git you a few miles out of town. Save you an hour’s walkin.’ My home’s out that a way so’s no one thinks twice seein’ me on the road,” said Elisha.

Lydia climbed in. Elisha’s horse snuffled. With a screech, the wagon rumbled north in the cool night.

Journeying from Miz Smith’s house had been easier than the first leg of her trip, just as the old lady had promised. Although the Blue Ridge Mountains were still to her left as she traveled north, their peaks in this part of Virginia were further off from the road, lower and not as dramatic as they had been in Albemarle County. The Carolina Road in this part of Virginia followed a flattened pathway.

Even so, Lydia had been exhausted by the time she saw the chimney smoke from Culpeper’s homes. She’d had a couple of little crying fits towards the end of her walk, her thoughts flying back to Chestnut Grove. But, then, she reminded herself that Chestnut Grove would never be what it had been. The Colonel was dead, and, with his demise, his protection evaporated. The enslaved of Chestnut Grove by now were all divvied up, split amongst the Colonel’s heirs. Still, she yearned, for Aunty and Caesar especially. She certainly didn’t miss scrubbing the Thornton’s iron skillets and emptying their chamber pots without so much as a “thank you” sent her way. Now, she had hope. If she could get up north to Pennsylvania and maybe on to Canada, she could be whatever she wanted to be. She’d be free. She wasn’t sure how she’d earn her bread, but she’d be the one to profit from her work, not some so-called owner. Maybe she’d be a seamstress like Miz Smith. Lydia loved horses. Maybe she’d run a livery. She’d scrimp and save and get enough money to buy Aunty Beebee and Caesar’s liberty so they could all live together again. Only better, because they’d all be free. Pondering the opportunities of freedom cheered her up and made her lonely day bearable.

By dawn, the little abandoned shed had beckoned her, offering respite. Situated at a burned-out farm site, Lydia figured no one would bother her if she slept here. With a quick prayer, she tumbled into a deep sleep.

Aunty Beebee sat at the wooden table in the summer kitchen, chopping apples with her favorite kitchen knife. Lydia nudged the fruit she had peeled toward Aunty, doing her best to keep the older woman’s pile of fruit stoked. The heady aroma set her stomach to growling. Aunty looked up from her work, worry in her light brown eyes.

“Lydia be careful! Pay attention!”

A rumble of thunder rolled out, wakening Lydia from her dream. Narrow spokes of light poked between the shed’s dilapidated gray boards. Lydia peeked out through a crack in the walls.

“That’s funny. Not a cloud in the sky, yet it’s thundering,” Lydia thought to herself.

Digging into her poke, Lydia pulled out a misshapen apple she had picked on her walk. She ate a chicken leg, worried since only two wings remained. Remembering Miz Smith’s recommendation and feeling ill at ease by Aunty’s dream warning, she pulled out the brown calico dress and rust jacket.

“Might as well just leave this slave dress here. That way I won’t have to carry it.” Lydia stuffed the cheap green cotton dress and purple head scarf that marked her as enslaved into a corner, covering them with rotten wood and straw. She reached back, plaiting her copper curls and tucked them into a crocheted snood Aunty had tucked into the poke. Her blood-crusted left foot caught her eye. Her shoe had torn in the early morning hours. Lydia’s shoes were straight-last; each one fitting either foot. She put the torn shoe on her right foot and tucked a square of linen over the scraped bloody side of her left foot.

“That’s the best I can do, for now. Maybe my feet’ll toughen up soon.” She was ready to walk.

From a distance Lydia’s white heritage could shield her. By passing as a full-blooded Caucasian, she hoped to gain the liberties granted the race in Virginia. She knew few white girls had her height but couldn’t change her tallness. Lydia planned on following Aunty’s recommendation — to avoid contact with anyone and make herself scarce as she traveled toward freedom. She had never been so lonesome.

Venus winkled in the early twilight, yet the thunder continued and grew louder as Lydia drew near the Rapidan River.

“Must be raining the other side of the mountains,” she thought to herself.

She could see a line of trees snaking through the grain fields ahead, marking a river path.

“Maybe they’ll be some pawpaws by the river.” Her mouth started to water just thinking about the rich custardy fruit. Drawing closer, a dank smell hit her.

“That water stinks. I won’t be drinking it. I’ll look for a spring up the road.”

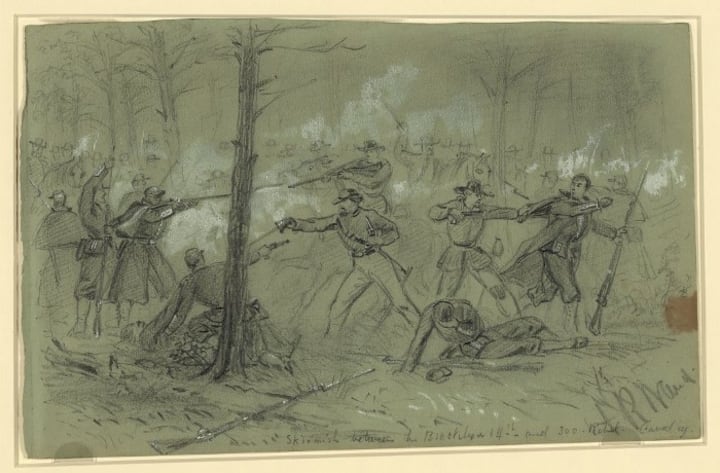

A thrumming sound and the crack of gunfire joined the thunder.

“That’s cannons, not thunder!” Lydia rushed toward the river, looking to hide in the brush along the banks if need be. She spied some blue cloth in the brambles at the side of the road; drawing closer, Lydia gasped. The pile of cloth was a Union soldier, his blue cap blown five feet away from his disfigured face. He was clearly dead. His saddled bay mount, white-eyed and skittery, reins caught in brambles, gave a snort. The girl approached quietly, unsure.

“Whoa, girl. Shh…You’ll be alright.” She gently took the reins, patting the mare on the nose. The big horse quieted at her touch. Lydia reached into the cloth bag, pulling out her last apple and offered it with an open, flat hand. Soft lips accepted the gift. The horse, at least, was fine. Lydia looked down at the dead soldier.

The man’s red hair shone in a beam of light from the setting sun. His feet were shod in new-looking leather boots. Lydia glanced at her feet, then his.

“I am so sorry, Sir, but I need your boots. I truly do. You won’t need them to walk around heaven, but I have to make it north.”

She thought for a minute or two, then tied the horse up and set to work. When she was done, the soldier was in his skivvies and she was now in full Union regalia, with a mount to boot. Aunty would be proud. She said a short prayer over the dead man after closing his eyes. Engrossed in her tasks and distracted by the sounds of battle, she didn’t hear the Union officer’s horse till he was ten yards away.

“Halt! What’re you up to, soldier? Who’s that in the ditch? What the….?” A stern-faced man astride a barrel-chested gray horse glared down at Lydia.

Her borrowed clothes were askew. She had missed a button in her haste.

“You’re not a soldier! Who are you? Are you a secessionist trying to probe our lines? Speak up,” he barked.

Startled, Lydia stepped back, caught her borrowed boots on a root and fell, dislodging her cap. Long braids of hair tumbled loose.

“Why, you’re a girl… What in tarnation are you doing in that uniform?” said the Union officer.

Lydia stood up straight.

“I’m sorry, Sir, but I just have to get myself north. I’ve been walking and walking for days and my feet are so sore and my clothes so cumbersome and he doesn’t need them anymore. Please, Sir, don’t hurt me. Just let me have these shoes and go on my way. I can give you back the other clothes if you want. But I have to get north, and I need the boots. Can you help me, please?” Lydia said.

The soldier just stared.

“Where’s your family? There’s a war going on here and it’s no place for a girl. I can’t spend all day talking.”

Lydia quickly explained. Her parents were dead, and she had been enslaved and was heading north to be free. She’d been told she could trust the Union Army. Couldn’t he help?

Begrudgingly the man agreed.

“Quick. Get over here. We’ve got to cut off them plaits. You’ll be safer kitted out as a soldier than as a girl. The Colonel can figure out the rest. Just let me do the talking and remember, your name is ‘George Washington Smith’ no matter what. Mine is Silas Green,” said the soldier.

An hour later two Union soldiers trotted north along the moon-brightened Carolina Road. Silas sat atop the grey like a sack of potatoes. His slender companion rode her bay with rare grace. A soft smile playing on her face, Lydia reached up and tapped the cowrie shell through her uniform shirt. “North.”

About the Creator

Diane Helentjaris

Diane Helentjaris uncovers the overlooked. Her latest book Diaspora is a poetry chapbook of the aftermath of immigration. www.dianehelentjaris.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.