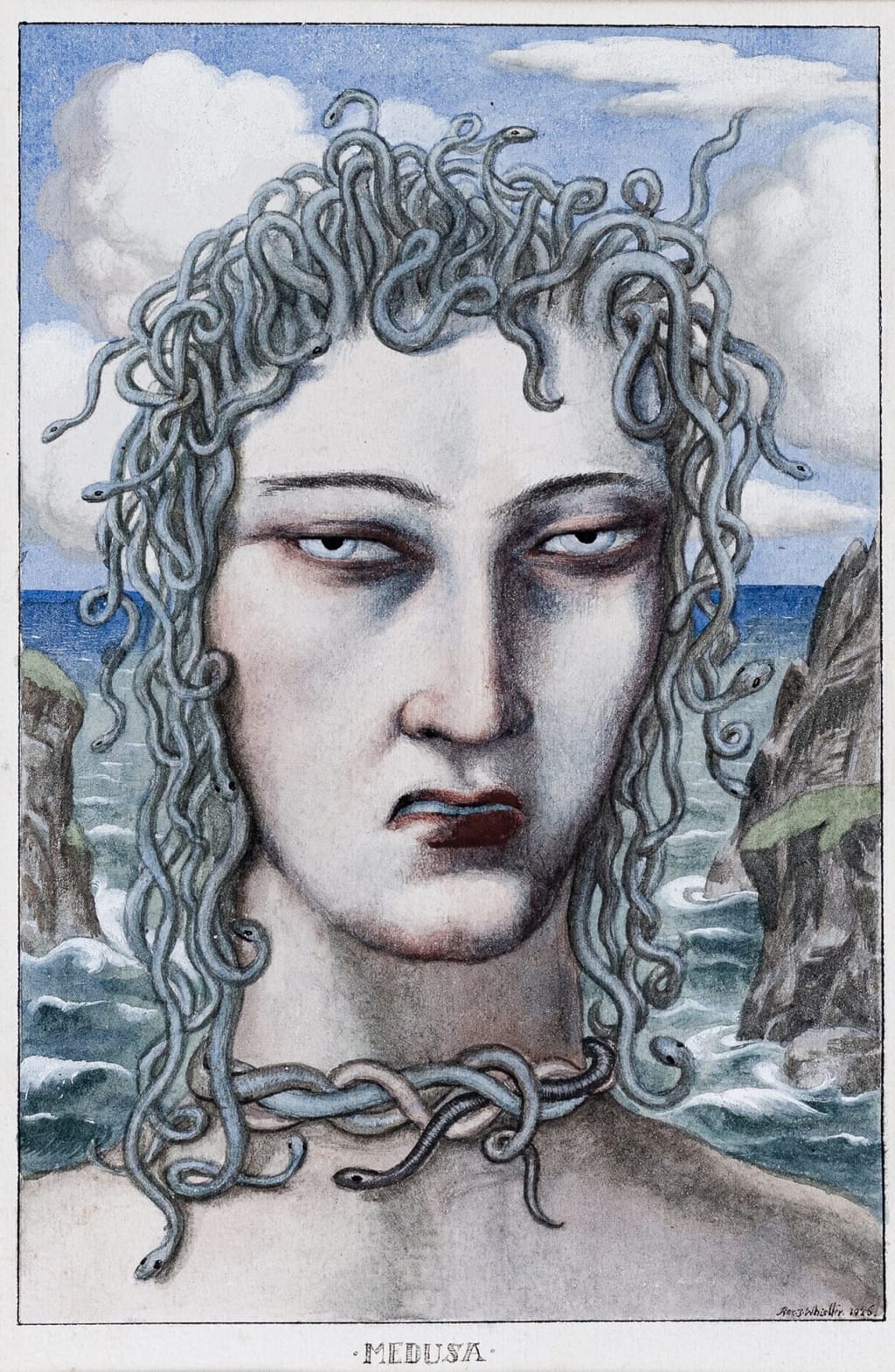

Medusa

A short story of adventure in a small town

“What’re we gonna do, Niko?” Nine-year-old Chris glanced down at his brother as the two trudged home from the school bus stop.

Eight-year-old Niko’s hazel eyes met Chris’s brown ones. The boys looked like two cookies from the same cutter but decorated with different icing. Nearly the same size, definitely the same sturdy shape, only their coloring varied. Chris had his father’s black, curly hair and dark eyes. Nick’s hair was light brown and wavy and his eyes, hazel in a half-hearted nod to their mother’s blondness.

“Daddy’s birthday is next week. We ain’t got no money. Never do. What can we give him?” said Chris. He kicked a small stone into the ditch running alongside the gravel road. The white rubber toes of his black high-tops bore the scuffs of many such boyish actions.

“I ‘spect we can make him something. Like we did last year. Whittle another bird or maybe a horse. He’d like that,” said Niko.

“But we already did that plenty of times. I want to buy him a gift. Maybe a book. They got a lot of books in town. McCrory’s store must have one about those heroes and gods and goddesses he likes to talk about. He’s only got his Greek Bible and that English book about Greek history, and he reads most every night after dinner. Must get sick of reading the Bible all the time.”

“Well, I don’t know about that, Chris. Daddy told me the Bible helps him when times are hard. I asked him once why he didn’t go to church with Momma. Said those hillbilly holy rollers weren’t for him. He was Orthodox — whatever that means — and there just wasn’t one of his churches within a hundred miles, so he’d read his Bible on his own and pray and think holy thoughts. But you got a point there. A book would be a good present. Let me think.”

They walked on in companionable silence. Winter had ended and even the fickle early spring was gone, yet hot weather was yet to come. With no need for jackets, the boys’ arms swung free, Niko’s striped red and white tee shirt blazed in the sun like a spotlight. Dressed in a faded beige and green checked shirt, Chris blended in with the woodsy setting.

Up ahead, a white clapboard farmhouse squatted in a small clearing atop its own hillock. A sea of tree-covered hills, green with springtime, undulated around it. As the boys drew closer, the shabbiness of their home became clearer, as if an invisible hand was tightening the focus of a view seen through a giant telescope. The asymmetry of the walls, the dipping of the frame on its foundation, the missing paint and planks in the clapboard, the cracked windowpane — all announced the Moshos family’s poverty. The missing chickens and geese, the lack of even one cow, and the absence of barnyard aromas told visitors this was no working farm. No. It was an old farm failure on its last legs as a rental, headed toward fate as a practice fire for the Ironton Volunteer Fire Department or maybe an abandoned and tumbled pile of lumber, bricks, and rocks. In the meantime, Dimitrios and Nancy Moshos sheltered here and did their best to raise their two sons.

Life in the mountains of southern Ohio had never been a sure bet. Now, in the 1960s, the area around Ironton was rusting away, deteriorating in an economic tidal wave of failing industry.

Dimitrios, a son of Sparta, an immigrant, had tumble-weeded into Ironton two decades earlier. He was a handsome, if short, man with the long straight nose and almond eyes of his homeland’s ancient pottery. His black curls tumbled about his head like something alive as he bent to his work at the auto shop, glossy as the coat on a groomed stallion. His eyes were amber and his teeth sparkling white.

The Greek had hitched his fate to local girl Nancy Atwater and joined the legions scrabbling for a living in Appalachia. Nancy, unlike many in the community, had stuck it out and graduated from high school. Dimitrios told her she was the smartest and most beautiful woman he’d ever known. Together, the married couple often talked about their future and saved every penny to bring their dream of owning their own business to life.

“Guess what, Niko?” Chris asked the next afternoon as the brothers walked home from the bus. It was Friday and there was a weekend springiness in both boys’ steps. “I think I found a way we can make money.”

“Yeah? What?” said Niko, his brown eyes alert.

“Well, Jimmy Grandstaff got bounty money for catching snakes. Says the town pays five whole dollars for one snake. Has to be a bad snake, a pest, not a garter snake.”

“What’s a bad snake? A copperhead?”

“Yeah, a copperhead or a water moccasin. You know. Bad snakes, poisonous ones, ones that cause problems.”

“Why’d they want to do that?”

Chris shrugged his shoulders. “I don’t know exactly. Maybe they want to protect the people. Sounds kind of stupid to me. There must be millions of copperheads in these hills. They’ll never get them all. But if the town wants to pay, why shouldn’t we make some money? Jimmy made ten dollars We should be able to get that much at least.”

“Yeah,” said Niko. “We could get Daddy a good birthday present. Do we have to catch copperheads? They’re kind of hard to find.”

“No. Remember that place we found down by the big creek? The place where it gets ready to empty into the Ohio, but is sort of swampy?”

“Yes…the place with all the water moccasins. We could catch them easy.”

“Well, we’ll have to be careful, but I think we can. Can’t tell Momma though. She hates us messing with wild animals and snakes. Don’t say a word, Niko. Promise?”

Niko shot his thin arm out toward his brother, linked his little finger around Chris’s, and made a pinkie swear. He would tell no one. They ran the rest of the way up the hill to their home. Apollo, their black and tan mongrel hound rose from his nap on the porch to bark and bray. Each boy patted Apollo, then went inside.

“What’s all the excitement, boys? Did you get an A on a test or maybe even a B?” asked their mother. She didn’t wait for an answer. Nancy Moshos wiped her hands on her print apron and tucked a strand of lank blond hair behind her ear. “Let me fix you a snack to hold you over till dinner.” She reached into the 1940s Frigidaire and pulled out a half gallon of milk. A plate with two squares of cornbread sat on the table in the middle of the kitchen. Her sons raced off to wash their hands.

That evening, cool air sneaked into the boys’ bedroom, like long fingers reaching through the cracks in the windowpane and under the wooden sash of their window. Each child lay on their narrow bed, covered with mismatched homemade quilts. The air carried the scent of the surrounding land, a mix of soil, old decaying leaves, and fresh growth. A hooty owl called as he hunted prey.

“Chris, we’re getting the snakes tomorrow, right?”

“Yepn. I’ve got the gunny sack and rope hidden out in the yard. We’re all set. But we need to get up early. We’ll tell Momma and Daddy we’re going hiking which is true and will be back for dinner. We can take a baloney sandwich or something. Now go to sleep and rest up.”

Downstairs Dimitrios’s curly head bent over his Bible. A smile bloomed on his handsome face as the murmurs of his boys up in their bedroom and the rattle of his wife at the sink filled his home. “I have everything I ever want or need,” whispered Dimitrios.

A few nights earlier, he had suggested to Nancy that he teach his sons Greek. “It’s an important language, Nancy. You can say things in Greek that you can’t in English. They have an important heritage. Besides, one day they may want to travel to Greece.”

“I don’t know, Demi. Who’ll they talk to? You’re the only Greek in town besides old Mr. Stratos and he hates children.”

“No, he doesn’t. Anyway, they can talk to me, their father.”

“Well, go on ahead. I know they like hearing about Greece.” Dimitrios had raised his sons on tales of and from Greece since they were babies Their toddler monsters were Cyclops. Ulysses was a hero and Apollo — well, he was their dog.

Not too long after the spring morning began with an explosion of lilac and pink and orange in the east followed by a rising fat sun, the Moshos family sat together for breakfast. In honor of the weekend, Nancy fried flannel cakes and served them with sorghum syrup.

“Momma, why do we call these flannel cakes? Aren’t they pancakes?” asked Chris.

“Well, I always thought it was because flannel cakes felt like flannel if you touched them, soft-like. They look like pancakes, only made a little different. The eggs are split apart and separated. That’s the secret. They’re a special kind of pancake, like Saturdays are special kinds of days.”

“Oh. Well, they don’t taste like flannel. They taste great. Wish we had them every day,” said Chris.

Dimitrios laughed. “If we had them every day, they wouldn’t be so special, son. Well, I guess I’ll get busy. Gotta chop some wood. Thanks, love.” He kissed his wife.

Nancy’s cheeks glowed pink. “OK, boys, let’s go. I heard you’re hiking, and I’ve got sandwiches and apples all ready. Scoot. I have to clean, sweep, mop, dust. You name it. You two can do your chores this afternoon.”

The boys headed downhill. Chris darted off into the grass half-way down the hill and returned with a large burlap sack and length of jute rope. At the bottom of the hill, they followed the road for a quarter mile, then turned off onto a narrow footpath.

Not long after, an old man, bamboo fishing pole over his shoulder, walked toward them. A faded Cincinnati Reds cap sat at an angle atop his white hair. His bib overalls carried the history of his life in stains, small tears, and patches. Working his mouth around a chaw of tobacco, he stopped to while away a bit of the day with the brothers.

“Morning, boys. Lovely day to fish. Not necessarily to catch a fish, but still a great day to drop a hook in the water and sit on the banks of the Ohio. What’re you two up to? Not fishing I see, though you must have a purpose for that there gunny sack.” His blues eyes roved from Chris to Niko, then settled back on Chris.

“Morning, sir. We’re going snake hunting. Sometimes we fish with our Daddy,” said Chris. “Did you get any bites?”

“Only a couple. Well, you boys enjoy your snake hunting, though I can’t figure out why in the world you’d want to catch one of them. Fish tastes better.” With a tip of his baseball cap, the elderly man shambled off.

When he was out of earshot, Niko turned to Chris. “Why didn’t you tell him about getting money for the snakes? He looks like he could use a dollar or two.”

“Never talk about money with strangers, Niko. That’s what Momma says. Money is personal business. Don’t want him scooping up all the snakes. Snakes are gonna be our business.”

After a beat or two of hesitation, Niko soberly nodded.

Fishers had created the trail to the Ohio River. Some fished because they liked the taste of fish, others because they could not afford meat and needed a little protein to go with their meal, and still others fished to escape the tedium and turmoil of their life. The river had never been generous, and most fishers were lucky to get more than two on their hook. Chris and Niko fished a few times a month with their father. Much more often, they followed the trail as part of their boyhood explorations. They pretended to be knights on a quest, Spartans fighting the Athenians, cowboys on a cattle drive, Shawnees on the warpath, and hunters on safari. The last year or two their wanderings had become less fanciful and more exploratory. What was out there? What was happening on the river? Where were the barges going? What did they carry? Where are the Indian arrowheads? Can you really start a fire by rubbing two sticks together? The outdoors was their playground and their schoolroom, all in one.

The sun climbed steadily, leaving the eastern horizon behind. By the time it reached about a third of the way to its zenith, the path had narrowed. Downward, every downward, the trail sought the river down below. Tall sycamore trees, those harbingers of wet ground, replaced the upland trees. Bushes, brambles, and briars challenged anyone to leave the path. Morning birdsong ceased as the birds dozed in the growing heat.

Turning eastward with the trail’s curve, the view opened up ahead. The mighty Ohio River, flat and featureless, began to fill in the viewscape. There’s a menace to the big river, a hint to anyone paying attention of tremendous power roiling below the smooth surface. Oh, every now and then, it reared its head and made its evil known — choppy waves, drownings, boats swept away, floods and such — but mostly the waters were content to roll on, gathering strength as it made its way to the Mississippi.

Dark as steel, its industrial persona was highlighted by a barge being pushed downriver. Long and flat, powerless, shaped like a skinny tablet of paper, rectangular shipping containers clustered in its middle. The boys paused to stare.

“Come on, Chris. Let’s go. We can see a barge any old day.”

“I want to see how many barges this tug is pushing.” Chris caught his brother’s eye. “Well, OK, Niko. You’re right. Let’s get to the snakes. We can walk and look at the river at the same time.”

Their high-top canvas gym shoes had smooth soles. As the trail steepened, their attention moved to their feet. Slipping could tumble them into the river lurking below. Both could swim, but swimming was for another day. Today they had things to do.

Reaching the riverbank, the trail widened and bifurcated. Without hesitation, they went west.

“You know, if we walked far enough, we’d reach Cincinnati. Wouldn’t that be fun? Walk all the way to Cincy. Maybe see a Reds game or go to Coney Island. If we catch enough snakes, we could buy Dad a gift and get tickets to a ball game. Or get Momma a rose bush. She’d like that.”

“Yeah,” said Niko. “We could all go to a game” A fine sheen of perspiration had bloomed on his forehead. He swiped it away by pulling his tee shirt up from his belly. A smudge of dirt smeared across his brow. “There’s the tug, Chris. That one has three barges it’s pushing.”

“I saw one once pushing five barges. Daddy says he’s seen six.”

“Chris, can we eat before we catch snakes? I’m getting hungry.”

“It’s too early, little guy. Let’s at least get to the creek before we think of lunch.”

Traveling along the Ohio Riverbank was smooth going and the boys made good time. The path stopped at the wide mouth of a creek feeding into the Ohio.

“This is more like another river, Chris. It’s big.”

“Don’t worry. We don’t have to cross it. Only have to go up a little ways to where it gets swampy. Crawling with snakes up there. You still hungry? We can eat here then we won’t have to carry our lunches and the snakes.”

Sitting down on the hard-packed dirt of the trail, each boy’s grubby fingers soon wrapped around a baloney on white bread sandwich. Nancy had packed each child an apple and managed to scrounge up a small bottle of Coca Cola for them to share. Chris pulled out his pocketknife, found the bottle opener on it, and flipped off the top. “Here, Niko. Have some pop. Just save me a sip.”

“Mmmmm,” Niko’s eyes closed in mock ecstasy as he chewed a too-large bite of his baloney. He reached for the narrow-necked green Coke bottle. “Thanks.”

Few sounds broke the quiet — the occasional flop as a fish broke the calm shoreline water, the rustle of a chipmunk or bird in the brush, the barely perceptible hum of tiny insects.

Wadding up the waxed paper from the sandwiches, Chris tossed them into the creek. He set the empty Coke bottle to the side of the path. “Someone might want that. Never know when a bottle will come in handy. Come on, Niko. Snake time!”

Heading up the creek bank was rough going, weedy and tangled. Their destination was close, an outpouching of the creek above its mouth, an area of shallow water with overhanging trees — in other words, a swamp. The exposed roots of the biggest trees created cave-like shelters with watery bottoms, perfect hidey-holes for water moccasins.

“Okay, Niko,” whispered Chris. “Be quiet. It’s warm enough now they should be asleep. You hold the bag wide open when I get one, wide as you can so you don’t get bit. I’ll use this stick. Just have to be quick. Don’t want to get bit.”

Niko’s eyes rounded. “What happens if we get bit? Will I die?”

“Won’t let that happen, brother. Don’t worry. All you do is keep that big old gunny sack wide open and then close it up quick when a snake goes in. It’s so long, they won’t be able to crawl out before you close it. Plus, remember, they’re sleepy. Takes a while to wake up. They’re meaner at night.”

It didn’t take long to find the first water moccasin snoozing in the sun. Dark brown, with a pattern in its midsection, and a snub-nosed head, it looked harmless enough.

Chris, his mouth firmed into a straight line of concentration, extended his five-foot stick with a forked end under the snake’s midsection. The animal slowly coiled into an S-shape; its big head sleepily waving in the still swamp air. The stick wavered a bit. With a soft grunt, Chris poked the snake into Niko’s gaping gunny sack. Niko closed the sack, his brows knitted into a frown. Done, he looked up with a grin.

“We did it, Chris. We did it. Let’s get some more. Woo hoo.”

Over the next hour, the two harvested their bounty of water moccasins. Most were between a foot to a foot and a half long. All but one went quietly into Niko’s bag. The last one, a good two feet in length and a bit fatter than the others, responded grumpily to having his nap disturbed. He (or she) pulled his block-shaped head up as Chris raised the forked stick into the air. The viper opened his mouth and displayed the startling white lining of his maw, his “cotton mouth.” The tip of his tail twitched. He hissed.

Chris dropped the stick. “Close the bag and run, Niko.” The two were off like a shot, hightailing it south to the big river, the Ohio. If there had been a bridge, they might have run all the way over it to Kentucky. The snake wiggled off toward the north. The snake collection was complete.

Panting at the banks of the Ohio, Niko set his bag on the ground. He had wrapped the rope around the top. “Oh, my, Chris! That was scary! Did you see that snake’s mouth? I don’t know if I want to do that ever again.”

“Yeah, that was fun though too, don’t you think?”

“Well, maybe a little.” Niko’s face held a dubiousness to it.

“Here, Niko. Let’s fix that sack.” Chris unwrapped half the rope, cut it, and lifting the bag, wrapped the new piece a foot below the neck of the bag. He knotted it, then knotted the remaining rope at the neck. “That way you can hold it at the top and not worry about a snake sneaking up and biting you through the sack. They’ll sleep anyways, but just in case. Now we got to get to town to collect our bounty money.”

“Hey, Chris. Don’t you think the inside of this bag must look like that Medusa lady Daddy likes to talk about, the one in his stories.”

“Yeah. You’re right. But I’m not looking in that sack. Unh unh. Not me. You neither. We’ll let the town take care of that. They’re the ones wanting the snakes.”

The trip to Ironton was quick, hastened by hitchhiking a lift with a farmer driving a truckload of spring vegetables to the town market. He allowed the boys to ride in the truck bed with only a quick glance at the gunny sack. If the farmer had looked long enough, he might have seen the gentle writhing and heaving of the brown burlap. As requested, he dropped Niko and Chris off at the town government building. He asked no questions. He merely tipped his brimmed straw hat and flopped his big tanned hand in a goodbye wave.

Ironton Town Office read the wooden sign. Underneath was lettered Home of the Ironton Tanks, the Nation’s First Professional Football Team. Blue and yellow pansies filled the flower bed below the town sign. The lawn was meticulously maintained as was the one-story brick building. As a small town with a budget to match, the Town Office housed all town services, including the jail. Not everyone in town considered the jail a service, but a government couldn’t please all the people even part of the time.

The Moshos boys entered through the double doors. Niko was careful to keep his sack off the ground. A middle-aged woman at the reception desk chatted into the telephone.

“Yes, honey. I agree. Hmm hmm. Never do know, do we? Well, I gotta go. Got some visitors. Bye bye.” She hung up the phone, her long manicured nails flashing flamingo pink. She smiled, the same flamingo outlining her full lips, the same flamingo pink as her cotton dress. The receptionist was a redhead, and the overall effect was of a strawberry glow emanating from behind the desk.

“Well, good afternoon to you, boys. What can I do you for, I mean what can I do for you?”

“We got some bad snakes to turn in, ma’am. You know, for the bounty money,” said Chris. He tacked a smile on the end of his statement and flicked his dark eyes at Niko. Niko took the hint and gave a broad cheesy grin to the receptionist. According to the plaque on her desk, her name was Pinkie. Pinkie Strauss.

“All righty. Well, how many snakes you got? She glanced at the gunny sack.

“Nine. We got nine snakes. Water moccasins. I think we get five dollars a snake, right?” said Chris.

“Yes, you do. I’ll get your money together and get someone to take those off your hands. Is it OK if I give you the money in singles and fives? I’m all out of twenties and never seem to get any tens.” Her flamingo pink lips curved in a practiced smile. She drummed her nails on the desk.

“Huh? Oh, yeah, singles and fives are fine,” said Chris.

“OK. First, let’s turn in the snakes.” She picked up her phone and punched on a button. “Hi, Jimmy. Got some bounty for you to dispose of. Uh huh. Snakes. Nine snakes. OK, dear.”

She looked up at the boys. “Deputy Linville’s on his way. I’ll count out your funds and get you a receipt.” Pinkie Strauss opened a drawer, withdrew a half-sheet form, slipped it into her typewriter and began banging away. Miraculously, her long nails held true. She glanced at her mesmerized audience of two. “What’s your name, honey?”

Chris told her.

“Oh, you all are Nancy’s boys. I went to high school with your mom. A right smart woman. I think I met your daddy once, too. Long time ago, before he knew your Momma. I pretty much know everybody in this here town.” The form completed she handed the original to Chris and kept the pink carbon copy.

Next, she pulled out a metal box from a side drawer and opened it with a small key she wore on a stretchy coil around her wrist.

Niko shuffled his feet nervously. A bulge moved in the sack as he let it touch the floor.

Pinkie withdrew a stack of bills, counted out a small pile. Most of the bills were soft with use. A few carried check marks from the bank; others had tattered corners. Even the money in Ironton seemed rusted.

A tall sandy-haired deputy strolled in from the jail-side of the town office. His tan uniform was spotless, his short sleeves each rolled once, exposing massive biceps. A dark brown stripe highlighted the outside of each trouser leg. Red hair on his forearms caught the light. The wide belt around his waist gleamed black and dangled a pair of silver-colored handcuffs. His sidearm was holstered in matching black leather. The two boys’ hungrily ate up his shining example of masculine power. Their identical brown almond eyes roved from the gun handle to the boots and back to the gun.

“Hi, Pinkie. Where’s the snakes.” Deputy Linville caught sight of the boys. “You mean to tell me you two got some poisonous snakes? Your parents know about this?”

Both boys looked terrified.

“Oh, never mind. Just hand me the bag and I’ll take care of them. I’ll trust you to talk with your folks before you evert do this again.”

He grabbed the bag and strode back toward the back exit. The bag bumped along the green tile floor and erupted into a roiling, quivering mass.

The boys’ eyes returned to Pinkie and the reception desk. Finished counting the money, she put it in order, locked the box and handed the forty-five dollars to Chris. “There you go, young Mr. Moshos, be sure to tell your Mom…”

The rarely heard and horrible sound of a man’s scream split through the air, followed by loud curses punctuated by gunshots.

“Dead. The snakes are supposed to be dead. Dead. Oh, my Lord! Goldarned kids…”

With that comment clear as day, Chris and Niko didn’t need to look at each other to know what to do. They didn’t tarry to count if nine shots rang out or only six or so or maybe more than nine. Like their Greek ancestors, they knew when it was time to run a marathon.

Pinkie might not have been Greek, but she too knew it was time to scat and headed for the door. It was her last day as town receptionist.

Epilogue

Dimitrios blew out the candle on the chocolate cake Nancy had baked for him. A brightly colored copy of Bullfinch’s Mythology lay beside the cake. The book had only cost the boys five dollars, just one-snake’s worth of labor. Their mother had taken them the day before to the bank and set up a savings account “for college’ with the remaining bounty money.

“This way you can get a safe job when you grow up, safer than catching water moccasins.” Her eyes twinkled and the dimple in her left cheek winked.

As the smell of the extinguished candle filled the air, Dimitrios patted his new book. “I’ve heard this is a great way to learn the Greek myths. Thank you, boys. You didn’t need to do this. I love you all.”

“Oh, it was nothing, Daddy. We helped Grandpa Atwater tear down his old chicken shed in exchange for the book. We learned a lot, Niko and me. A lot.”

Nancy patted Chris and Niko each on the shoulder.

Niko smiled. “Do you think you could read to us about Medusa tonight, Daddy? I like that story.”

About the Creator

Diane Helentjaris

Diane Helentjaris uncovers the overlooked. Her latest book Diaspora is a poetry chapbook of the aftermath of immigration. www.dianehelentjaris.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.