The street sweeper on the corner of Main and Broadway was a lame man.

He was hired to sweep the outside of Building 49, a most important building, whose grand entrance was to be impeccably maintained. Before his first day of work, he was warned never to step inside and to stay in the shadows, out of the way of important business. Sweep when it’s empty, they’d said, eyebrows raised pointedly at his right foot.

The year was 1967, and the approaching months were to be known as both the summer of love and the summer of violence. But for now, the most pressing issue for the city was a rodent problem.

Barn owl nesting boxes had been set up all around Building 49, tucked out of sight atop ledges. Except for the occasional flutter, one might not have guessed they were even there, nocturnal as their inhabitants were.

That, at least, had been the hope. The unfortunate truth was that owl pellets and excrement had become a common sighting around the lot, to the dismay of the building’s wealthy patrons. And so, a hasty job posting had been made, and the lame Chinaman was hired to make sure that the building’s avian residents were as invisible as he.

The sweeper was a man by the name of Mister Ying, or Ying Ye-Ye to the Chinese locals. He carried out his duties diligently, staying out of sight as the building owners had asked, head bowed beneath a wide-brimmed hat and face hidden by a graying beard.

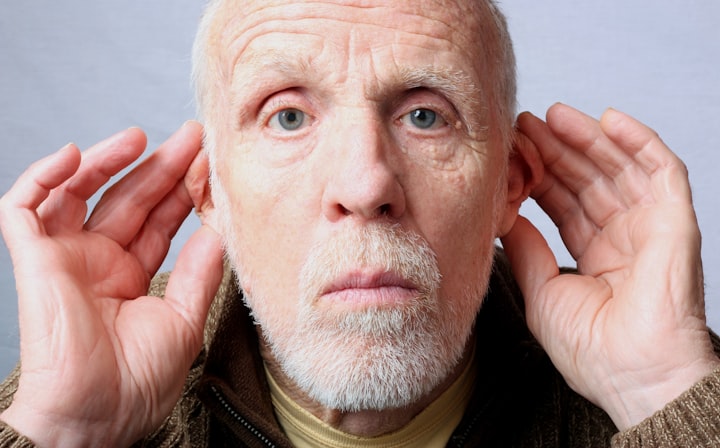

The man might have been handsome once, and of strong physique, but time had not been kind to him. Though he was in his late fifties, his dark, threadbare clothes and unusually twisted foot made him appear much older and frailer. He shuffled when he walked, leaning heavily on his broomstick, his right leg always a step behind. Step, shuffle, swish, swish.

Concerned as he was with items lost and littered, Mister Ying was discovering that people were a lot like owls. Just as one might discern the comings and goings of an owl from its pellets, there was much to be learned about people from their trash, from the things that were accidentally or intentionally ejected from pockets and handbags.

Just the other day, he had found a crumpled receipt from Chang’s Emporium, detailing a number of foreign herbs that only a trained herbalist could have possibly recognized, and hence, recommended. Of the items on the list, he’d found one to be familiar – an herb frequently prescribed for women recovering from miscarriages back in his home country. Mister Ying had felt a pang of sorrow and sympathy. The receipt had been thrown hastily into, or more precisely, towards, the trash bin by a young man who strode from Building 49 in frustration.

Another time, a handful of brass coins had jangled as they fell from a pocket flipped inside out in exasperation. The owner, a heavyset man with comically bushy eyebrows, was so intent on paying his trolley fare that he hadn’t bothered to pick up his coins. On board, he had pushed and cursed his way through the crowd to the last empty seat. The street sweeper had waited for the trolley to depart before picking up the coins hopefully, but they’d turned out to be Japanese yen, much to his disappointment. Mister Ying surmised that the gruff man was a foreign businessman.

Bus tickets, grocery receipts, shopping lists, old newspapers. They told stories of where one came from, where one was going, and perhaps even what one’s hopes and dreams were.

The street sweeper might have known all these things and more had he cared to, but as it was, his interest was reserved for select items, or rather, select people. The receipt, the coins, they had all been dropped by people who had entered and exited Building 49.

––

The best, and sweetest, part of Ni-Ni’s day was the moment her grandfather picked her up from school.

“Ye-Ye!” Grandpa!

Mister Ying steadied himself on his good leg as Ni-Ni raced out the classroom door and swung into his arms.

“Wa,” Mister Ying chuckled. “Soon you’ll be too big to do that!” Though his voice was playfully gruff, Mister Ying savored these moments as he would a hot cup of jasmine tea. And just as he dreaded the moment the tea would grow cold, so he also feared the day when his granddaughter would truly outgrow their after-school greetings.

“How was school, Ni-Ni?”

Before she could respond, an ensemble of expectant voices surrounded them in the schoolyard.

“Ying Ye-Ye! Ying Ye-Ye, what do you have for us today?”

Mister Ying pretended to think before whipping out a paper bag filled with cotton-candy-like pastries.

“Today, I’ve brought you sweets...” Taking one out, he held it up to his lip. The silky, white threads blended right in with his wispy beard. “Made from my beard!”

The children giggled as he passed out the Dragon’s Beard candy, each holding one up to their upper lip and growling as sage-like reptiles might.

“Ying Ye-Ye! Tell us the story of how you almost lost your leg again!”

“Ah, are you sure you won’t get scared?” The street sweeper crossed his arms in stern, grandfatherly fashion as the gaggle of children responded with a chorus of no’s. “Well, when I was your age,” he began. “I ate too many sweets, and first, I lost some of my teeth...” Here, he smiled widely to reveal a row of crooked teeth with two missing gaps. “Then, I almost lost my foot!” Mister Ying swung his right leg up dramatically, and shook the dangling foot towards the children. They ran away, squealing and laughing.

Satisfied with their bit of after-school fun, the children left the street sweeper and his granddaughter alone as they finally made their way out of the schoolyard.

Ni-Ni licked her lips, a couple of sugary strands from the Dragon’s beard candy stuck to her chin like silvery whiskers. She tugged on Mister Ying’s sleeve with her sticky fingers. “Ye-Ye? When will you tell me what actually happened to your leg?”

“Mm, perhaps when you turn seven,” Mister Ying said.

“Last year, you said when I was six!” Ni-Ni pouted and refused to take another step.

Mister Ying scooped the sulking child up onto his shoulder. “Ye-Ye must have forgotten he said that. Ni-Ni must forgive her old grandfather. Sometimes, he even forgets that his foot is injured at all.” He reached into his pocket and tickled her nose with something feathery. “That’s what happens when we have so much good in our lives to remember. Here, look what I brought you.”

Mister Ying placed the feathered toy into her small hands. He had affixed four barn owl feathers to a piece of rubber sole and a stack of Japanese yen coins with a bit of string.

“This is called a jianzi. It was a very popular game in my old village. Did you know that your Ye-Ye was the best player back then?”

Ni-Ni shook her head, distracted by the unbelievably soft feathers. Each was a creamy golden color, striped with brown like the back of a tiger.

Mister Ying smiled and breathed a small sigh of relief at his granddaughter’s wonder. “Let Ye-Ye show you some of his old tricks.” He balanced the shuttlecock on his right knee. “Watch and... learn!”

The jianzi swooped, fluttered, and flew through the air as Mister Ying demonstrated the traditional sport. Without ever directly kicking the shuttlecock, he caught and propelled it again and again into the sky with his hip, his chest, and even the top of his head!

Ni-Ni clapped and cheered. Her grandfather suddenly seemed more youthful, his lame leg swinging wildly as he hopped and pivoted. Their previous conversation gone from her mind, all she wanted now was to learn to dance with this marvelous toy.

“Ye-Ye, teach me! You must teach me first, before we show the other children, so that I can be the best player, just like you were!”

“Of course.” He smiled and took her hand.

Arriving home, Mister Ying and Ni-Ni were greeted by a stack of envelopes stamped with bold red letters, piled on the doorstep. Mister Ying picked them up hastily. He worried about a time when his granddaughter’s English would be better than his, and he would no longer be able to protect her.

The tiny room they called home was the basement of an apartment building. Inside, a lopsided dresser stood in one corner, and everything it held belonged to Ni-Ni. All the clothes Mister Ying needed were already on his back. A single window afforded only the dismal view of pavement and the hurried feet of passersby. Beneath the window was a cot for one.

Old newspapers plastered the walls, covering up holes and stains, and serving as English practice for the street sweeper and his granddaughter. The most recent clipping showed a critic’s review of a new restaurant called The Lucky Pig. Mister Ying had circled the restaurant name and written in Chinese, Ni-Ni sheng ri. For Ni-Ni’s birthday.

There was no garbage bin in the room. None was needed. Everything in the home had once been forgotten and abandoned. Mister Ying not only made sense of trash, he also made use of and gave new meaning to the things left behind. Even old food wrappings were transformed into flapping cranes to be hung above Ni-Ni’s cot.

To Mister Ying, nothing was worthless enough to be thrown away.

––

On the uppermost floor of Building 49 was a restaurant called The Lucky Pig.

The word on the street was that the head chef at The Lucky Pig was renowned for more than just his cooking. His cooking was great, no doubt, inspired by the great French chefs at Le Cordon Bleu with some added twists he had picked up from his globetrotting adventures. But along with this rare herb and that strange spice, he had also brought some Old World magic to the New World.

The head chef, a man by the name of Jonathan Wayne, was a shaman, and the waitlist to see him for his shamanic powers was longer than the Saturday night reservation list for The Lucky Pig. It was said that the shaman could perform miracles – heal illnesses, restore lovers, even solve legal cases. But the miracles always came at a cost, a trade. Though a large sum of money was most certainly involved, they required more than just coin.

It had been several months since Mister Ying had begun his role as street sweeper outside Building 49. The number of barn owls nesting nearby had increased significantly, as evidenced by the growing pile of feathers and pellets he swept away each day.

As he shuffled to and fro the shadows, Mister Ying noted that Building 49 also had its human regulars.

He’d seen the grumpy, foreign businessman on several occasions. The most recent time, the man had behaved rather oddly, quite unlike his usual self. He had exited the building triumphantly, waving an official-looking letter above his head, before ripping it in half. Aboard the trolley, the large man had collided with someone, but instead of cursing their mother as he normally would have, he had opened his mouth to find that no sound came out. He appeared shocked, and so was Mister Ying.

Piecing the trashed letter together, Mister Ying had made out the words, case dismissed.

On most days, such were the diversions that helped Mister Ying pass the time. But on Fridays, the corner of Main and Broadway was graced by the lovely melodies of an amateur violinist. Mister Ying welcomed her presence, though he never tried to approach her. She was American, with light, straw-colored hair and a birthmark, the color of red wine, that blossomed across her left cheek before spilling down her neck. In between songs, the violinist would pause to fix a scarf that she kept tightly wrapped around her lower face.

Mister Ying presumed that she was a composer as well, as he often saw her scribbling down music notes on scraps of paper.

It had been a while since he’d seen the young man with the Chang’s Emporium receipt, and Mister Ying wondered if his wife was doing well.

––

On a rare day off – he wasn’t sure which – the street sweeper took his granddaughter to see his “workplace.” Memorial Day perhaps? Mister Ying could not keep track of American holidays as they didn’t follow the lunar calendar.

As they made their way up Main Street, Mister Ying and Ni-Ni played a little game. He would flip hawthorn flakes, a fruity candy the size and shape of pennies, into the air, and Ni-Ni would catch them in her mouth. If you want to be a great jianzi player, you must practice your coordination, he had said, and Ni-Ni had excitedly accepted the challenge.

A block out from Building 49, Mister Ying was surprised to see a familiar yet jarring face. It was the young man he’d seen before, except the man was – there was no other way to put it – no longer very young. Within the span of a few weeks, the man had aged several decades. Creases ran across his forehead, and his eyes appeared sunken.

He was with his wife, a slim, petite woman with clear blue eyes and pale skin that seemed too delicate for the sun outside. The woman smiled and waved when she saw Ni-Ni, but her expression quickly became downcast as pain and sorrow welled up in her eyes. Her husband wrapped an arm around her comfortingly. Then, the woman’s gaze passed over Mister Ying, his shabby clothes and twisted foot, and her expression became one of repulsion. She turned to her husband and whispered something, frowning and pointing at the street sweeper.

Mister Ying gripped Ni-Ni’s small hand tightly. She looked up at him, confused by the abrupt change in her grandfather’s demeanor. “Ye-Ye, why is that lady pointing at us?” she asked.

Mister Ying could feel the young man – no, not young anymore – and his wife staring after them. The difference between his own rough appearance and that of his doll-like granddaughter suddenly struck him. Feeling uneasy, he hurried them along as best he could, foot scraping against the uneven pavement. But to his granddaughter, he said, “Nothing to worry about, Ni-Ni, nothing to worry about.”

They had just passed the entrance of Building 49, when Mister Ying caught sight of yet another startling figure. She was radiant, her golden hair shimmering in the sunlight, the birthmark on her face but a mere shadow of the old wine stain. Her hands, though, once quick and lively as they traversed her violin strings, were heavily bandaged, and her fingers appeared a few inches shorter.

Crumpled music compositions fell from the violinist’s broken hands as Mister Ying and Ni-Ni walked by.

––

The notice was shoved under the front door. The capitalized words atop were bold and unforgiving. Eviction Notice.

Mister Ying had three days to pay the rent and all his late fees, or both he and Ni-Ni would be forced to leave their tiny home.

Mister Ying pleaded with the landlord, but no, this was one strike too many. How many more chances would he need? The landlord was not a harsh man, but his elderly mother was ill and there was little money with which to pay her medical bills, so he could only sigh and shake his head at the lame man who spoke in broken English.

The notice still in hand, Mister Ying somehow found himself standing outside Building 49. Looking at the imposing, carpeted entrance, he felt left with no other choice.

He took a deep breath and hobbled through the entrance that he had only ever dared to sweep.

––

It was a Sunday morning, and Building 49 appeared empty as Mister Ying got on the elevator that would take him up to The Lucky Pig on the topmost floor.

On the 44th floor, the elevator doors opened to reveal a reception area, and immediately, the street sweeper was apprehended by two men in suits.

“Do you have a reservation with Mister Wayne?” The guards moved synchronously, and Mister Ying could hardly tell which one of them had spoken.

“Y-yes. Yes, I do.” Mister Ying tried, and failed, to sound confident.

“Mister Wayne does not take appointments on Sundays.”

The men grabbed hold of Mister Ying’s arms, one on each side, and proceeded to lead him back onto the elevator.

He struggled. “Please, I must see him. I know him! He’s an old friend.”

The men looked at each other and laughed. “I highly doubt that. We know exactly why you’re here,” one of them said. The other nodded in agreement. “We’re quite used to throwing out people like you.”

Mister Ying stumbled and his arm slipped from the guard’s grasp. Taking that to be an intentional act of resistance, the man kicked the street sweeper behind his right knee. Mister Ying’s leg buckled beneath his weight, and he fell to the floor with a gasp of pain.

“No, no, please. I just want to see him. It’s not for me!” He begged.

The guards shook their heads. Of the lowlifes who tried to enter Building 49, this was a persistent one, and one keen on sticking to his lies. They opened the elevator door and proceeded to half kick, half push the street sweeper in.

“Leave him.” The voice came from behind, quiet but commanding.

“Sir? We caught this man trying to sneak up. He says he knows you.” The guards were suddenly unsure, glancing uncertainly between each other.

“I know him indeed.”

Mister Ying looked around from his crumpled position on the floor. He didn’t recognize the stately figure dressed in white. The man’s face was covered by a white, formless mask from which golden hair peaked out.

“Come, follow me.” The man spoke to Mister Ying directly before disappearing down a long corridor. The two guards watched passively as Mister Ying dragged himself to his feet.

The corridor ended at a sparsely furnished office room, underwhelming for the famed chef of The Lucky Pig. Jonathan Wayne sat behind his desk, hands folded before him, and addressed the street sweeper.

“You wanted to see me?”

“I... was hoping you could help me.” Mister Ying didn’t know why the man had intervened. He stared at the blank mask, searching for the man’s eyes through the gaps. “I thought you were someone I used to know, but I was wrong. I am sorry.”

The shaman sighed. He removed his mask, and beneath, his face was just as pale and featureless as the mask had been. His lips were a thin line as he spoke, this time in the language of their home country. “No, you’re not. Old friend, it’s me, Wei.”

“Wei Xiong?” Brother Wei? Mister Ying shook his head numbly. “But how? Why?” All along, he had suspected that the shaman of The Lucky Pig was his old friend, living the American dream under a new alias, but this man sitting before him... It was as though someone had taken a knife to the Chinese man’s face and effaced his features.

“My friend,” the shaman’s smile was more like a grimace, “I’ve had to make my own trades to survive here.” Gesturing at his face, he continued, “Do you think they would come to me so readily if I wore my original face? No, this was my trade, my sacrifice for everything else you see here. This building, the restaurant. It all came at a price.”

Mister Ying fumbled for words. His leg throbbed, and he sank into a seat opposite the shaman. The last time he’d seen his friend, they had just arrived in America. That had been years ago, when Ni-Ni was still an infant in his arms.

It appeared that the shaman was thinking the same thing, for he said next, “How are you? How is your granddaughter?” It had been so long since the shaman had spoken to anyone in his native tongue, and seeing his old friend made him reminiscent. He attempted a chuckle. “Is she the same jianzi prodigy you were? I remember how all the village boys aspired to be as good as you, including me.”

The shaman’s words reminded Mister Ying of why he had come here. If Jonathan Wayne was indeed the Wei Xiong he knew, then there was still hope for Ni-Ni. Mister Ying pushed his chair aside and bowed before the shaman. His friend stood up, startled.

“Six years ago, you helped me save my granddaughter after her parents passed away during the Great Famine. You helped us leave our home country, to come to America and search for a better life.”

They both glanced at his leg. The shaman nodded, “Yes, I remember. And how has your trade... fared for you?”

“For a while, we were happy. Even though our home was small, we had a place to stay and food to eat,” Mister Ying said, and there was true gratefulness in his voice. “But I am getting older, and I worry about a day when I won’t be able to provide for my granddaughter. Right now, I cannot even keep our home, and soon, we will not have a place to stay. Please, help me make a better life for her. I gave her everything I could, but she deserves so much more.”

The shaman considered for a moment, then reached for Mister Ying’s arm. “Please, sit back down. Let us talk properly.” He returned to his own seat. “My friend, in the New World, the rules are different. The spirits are unhappy to be summoned somewhere they don’t call home. They require more... sacrifice. You know this.” The shaman said all this hesitantly, almost apologetically.

Of course Mister Ying knew this. He looked at his friend’s ghostly face. He thought about the people he’d seen leaving Building 49 – the violinist, the businessman, the not-so-young man.

“I would give up anything for Ni-Ni to be happy.”

The shaman closed his eyes and leaned back in his chair. When he spoke, he seemed to speak not to Mister Ying, but to himself. “Can you remember what it was like back in our old village? What it was like to kick a jianzi with both your feet?” His voice was barely a whisper. “I hear nothing is the same anymore – that the Cultural Revolution is destroying all the old traditions. I feel angry when I think about our village, but then I look at myself, and I realize that I can’t even remember what my face used to look like. My friend, these trades, were they worth it?”

“You know I would have given up both my legs and more to save my son and daughter-in-law.”

“It was too late for them. You did what you could,” the shaman said quietly.

“But it’s not too late for my granddaughter. She can have a better life if you help me,” Mister Ying insisted.

The shaman tried one last time to dissuade his friend. “Be careful what you wish for. Not all trades end the way you think they will.” When Mister Ying’s expression did not waver, the shaman sighed. “What you ask for will require a sacrifice not from you, but from your granddaughter. Her most treasured item.”

The street sweeper felt his heart twist, its beat lagging behind. No.

The shaman continued, “Her most treasured item... is you.”

Mister Ying hadn’t realized he was holding his breath, but at his friend’s words, he finally let it out, along with all his fears and inadequacies.

For years, people had looked down on him as though he were trash – repulsive, worthless, expired. Even the people in his own community looked at him with only pity in their eyes. It hadn’t mattered, or so he told himself, because Ni-Ni was worth the sacrifice. But secretly, Mister Ying had always feared that his granddaughter would see him the same way everyone else did. And so, he could ask for nothing more than to know that he was seen by Ni-Ni the same way he saw her – as a treasure.

He smiled. “Hearing that is enough for me.”

The shaman gave a single nod as he placed his mask back on. “My friend, you are no less admirable than you were in your glory days. I hope your granddaughter will always know how much she meant to you.”

A sweet smokiness, like the smell of incense from the temples in Chinatown, filled the room. This scent, however, seemed to invade more than just his nostrils. Right before Mister Ying drifted into unconsciousness, he thought he saw Ni-Ni in the room with them, laughing as she balanced a jianzi atop her head.

––

The street sweeper woke up on the floor of their basement room with no recollection of what had happened after his visit to The Lucky Pig. He wondered if he were dead, but no, it was Monday morning, and there was Ni-Ni sleeping soundly under the protection of her paper cranes.

Over the next few days, Mister Ying kept a wary eye on Building 49 and waited for his impending demise.

Was it to be a stroke of lightning from the sky? He listened to the weather forecasts, but there was no storm approaching. Would it be a heart attack? A stroke? Cancer? He felt nothing out of the ordinary.

Each night he tucked Ni-Ni into bed and wondered if it was going to be his last. Whether he would wake up in the morning to see her off to school, or whether she would wake up to find him stiff and cold.

His answer arrived late Wednesday afternoon. Just as he was leaving to pick up Ni-Ni, he heard a knock on the door. Members of the local authority stood outside, there on a report of suspected child neglect.

Preposterous, Mister Ying thought, but in his bafflement, he could not find the words to respond in English. They dangled another eviction notice that had been lying on the doorstep in front of him. What was this? They wanted to know how Mister Ying was planning on caring for his granddaughter. The street sweeper remembered belatedly that today was the last day they had in their home.

The authorities looked past the street sweeper into the small room, and all they saw was trash. There likely wasn’t even a bed for the child, they thought, shaking their heads at the dirty wrappings and newspapers strewn everywhere.

They collected Ni-Ni after school, and she never got to see her grandfather running after them as best he could.

So this was the trade. Not death, but loss. For a better life for his granddaughter. The pain in Mister Ying’s right leg screamed, but his heart cried even louder. Was it worth it?

––

Several months had passed since Mister Ying lost everything.

After a short-lived trial, Building 49 had gotten rid of its barn owl program. Though the owls found their homes convenient, they preferred to catch prey in more open areas and had done little to alleviate the rat problem. The owners of the building had decided on more modern methods of rodent control, and the owls would need to find new homes, as would the building’s sweeper need a new job.

It was a warm day, and the city was vibrant with music and sunshine. A couple made their way towards the corner of Main and Broadway. Their little girl skipped on ahead, kicking her jianzi with tiger-striped feathers.

The young mother commented that they’d purchased for their daughter all sorts of new toys, and even prettier shuttlecocks, but for whatever reason, the girl still preferred this one. The father, a rather elderly man stooped low on his cane, forehead marked by wrinkles, remarked that this shuttlecock did seem to fly better – perhaps it was something about those unique feathers. Alas, if only he could kick a shuttlecock around with his new daughter, the father said as he lamented his fading youth. His wife squeezed his hand, a gentle reminder of what his sacrifice had been for.

The family entered Building 49 for their dinner reservation at The Lucky Pig to celebrate their daughter’s seventh birthday. No one noticed the street sweeper who stood hidden in the shadows, tears streaking down his cheeks and into his beard.

––

Author’s Note: This story is based in a fictionalized U.S. city, loosely set during the historic year of 1967.

About the Creator

Lilia

dreamer of fantasy worlds. lover of glutinous desserts.

twitter @linesbylilia

Reader insights

Outstanding

Excellent work. Looking forward to reading more!

Top insights

Compelling and original writing

Creative use of language & vocab

Easy to read and follow

Well-structured & engaging content

Excellent storytelling

Original narrative & well developed characters

Expert insights and opinions

Arguments were carefully researched and presented

Eye opening

Niche topic & fresh perspectives

Heartfelt and relatable

The story invoked strong personal emotions

On-point and relevant

Writing reflected the title & theme

Comments (1)

This was fantastic!