Dirty Yellow Bungalow

A Shelter for Grief

It’s exterior had a layer of filth that clung to its cheap vinyl sidings, turning it to a muddied, fading yellow with streaks of brown. It had an almost brown, almost red picket fence that sat crookedly in between the sad excuse for a yard and the sidewalk. The north side of the house had two parking spaces, one for the house and one for the neighbours who ran a massage parlour out of a similarly small but slightly more well put together bungalow. The south side of the house was a charmless alley that nestled itself in between the house and a newer, shining building that had a 3 foot barricade made of stone protecting it from the vermin of Calgary’s east side. The house's backside, which faced west, was a parking area for a company that specialized in industrial vehicle washing mechanisms. The house looked as though it was the only home available to be lived in along the congested and dusty 11th St.

Inside, aged and dried spaghetti sauce was splattered against the kitchen cupboards in what looked like a bad attempt at painting abstractly. The sink looked older than the house itself with brown and yellow stains covering its damaged white basin. Directly across from the side door that entered into the kitchen was a doorway where a ladder to the attic could be pulled down. The stiff old pull down ladder creaked and squealed as I ascended it towards the mysterious attic. The windowless walls of the attic were painted olympic blue. Behind a pillar that stretched awkwardly in the middle of the room, a dirtied old cot laid spread out on the floor. To its side was a sweat stained tank top and socks that looked surprisingly clean. On the other side, a square trap door could be lifted from the attic floor. When lifted it showed the bathroom directly beneath it, giving any of the house's ghosts, ghouls and squatters a birds eye view into the shower. A tall lamp without the shade sat next to the empty walls, plugged into nothing.

Beneath the pull down ladder was a door that opened vertically and led to the basement stairs. I had to tilt my head backwards upon descending the stairs to avoid hitting my head. There were two squalid rugs layered on top of each other on the dirt floor of the basement. A laundry machine and dryer supposedly in working order sat against the pillars that upheld the structure of the house. Against the walls were small crevices where piles of garbage and old porno mags piled up into a filthy basement cocktail.

If you were able to look past the filth and squalor, the house was quite charming. A set of three windows in the living room faced out towards 11th street and there were two small bedrooms, equally messy, but fixable. The bathroom was small and crowded with a clawfoot bathtub where shower curtains showing photos of the Eiffel tower and exclaiming french phrases such as “Oui Oui”, “Bonjour” and “Je t’aime” hung from the ceiling.

After cleaning and tidying for several days, I agreed to rent the house for $700 a month plus utilities.

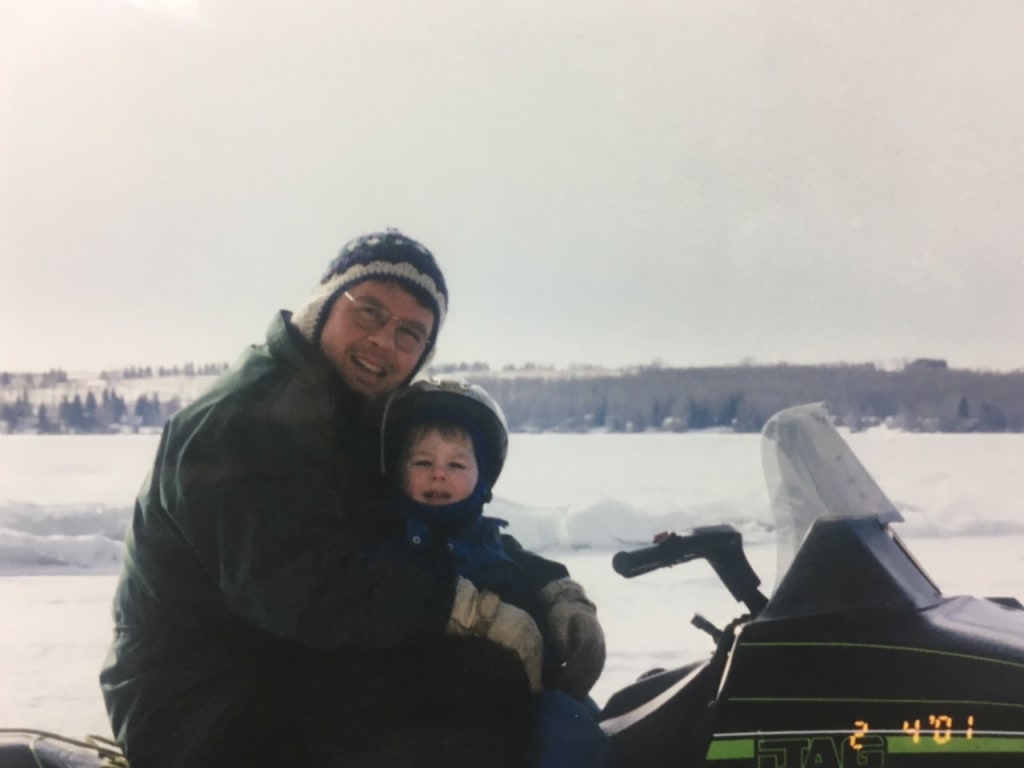

I moved into the house in early spring, just before my dad was sent to the hospital where he’d live out the last of his semi-coherent days. I traversed between the house in Calgary and the hospital in Red Deer each week. The rooms in the hospital were sterile but the view was sometimes nice. The dark impenetrable clouds that were so unusual in Alberta’s July’s hung over the hats of the city in a sinister fashion. The sorrows that filled the hospital rooms showed more life than the people in them. Grief danced along the halls, tears poured from the taps and pain sat patiently behind the distressed families, waiting to grasp hold of them for years to come. Fighting through the drowsiness of a cool early summer, I tried to shower my mother with my love to show her support through such trying times and to impress upon her that the wisdom and poise of her nearly lifelong partner had been passed onto their child. Upon my father I hoped to show him a side of myself that was more open and more loving. I was holding onto his hand, telling him things I’d never had the courage to tell him and looking into his face which looked as helpless as a drowning child's. Somehow some of the words that fell naturally from my mouth felt disingenuous, but I struggled to know what I could do or say that was true to myself. In the process of watching my father's body dwindle into a hollowed shell of what he once was, I felt my own self understanding do the same. As the days of despondence passed in dreary waves sitting behind hospital doors, I felt my soul grow weak and emotionless in those dull hospital bedrooms.

I was laying in bed when I heard the sound of a whispering voice outside of the bungalow. I stepped into the kitchen, wearing nothing but underwear and carrying a heavy wooden staff. After finding that no one was inside I moved towards the washroom where I saw a flashlight flickering through the blinds and the nose of a door hinge poking through the crack in the window. I stepped towards the window where the voice mumbled incoherently. I lifted the shades rapidly and looked out to see the face of a young man, with light blue eyes staring towards me in the darkness behind the house. I saw the fear of surprise as he looked at me through the window. We stood face to face, staring at each other and separated by only the glass window. I felt a familiarity with those eyes, as if I’d just looked into them the day before. Their depths attacked me and I felt a weakness in my chest. Suddenly the words ‘Fuck off’ muttered from my nervous lips in a voice that sounded much deeper than my own. In response, the eyes moved backwards slowly until they dissipated into the evening darkness.

The rooms in the hospice were much nicer than those of the hospital. Somehow that made it much more grim. Something about the sterility of hospitals makes it almost feel more natural. In the hospice death can feel curated, as though it's the hospice itself that is sending people to their graves. That being said, they do their best to make the painful process more pleasant. There was a jade plant that sat in the dark corner next to his bed. It had overgrown slightly from the pot that it rested in and I could see that a few of the leaves were browning but still I liked to look at its thick, smooth nodes.

Each day was spent sitting next to the bed where my father muttered in his sleep. It was a repetition of days that felt foggy and endless in their torture. My brothers and I looked each other in the eyes somewhat rarely and we reverted into our own sullen souls as we watched life slip away from the man that helped build us. I could feel my emotions moving inward and escaping from my own grasp and understanding. Left in the darkness to find a box of matches. In that dull and aching hospice room, I watched the nurse come to check his vitals and I watched her eyes widen in a slight alarm at what she found. I wondered how alarmed one could really be at finding a dead person in a hospice.

We returned to my mother’s house, which is what I’ve called it ever since he died. There were too many family members and friends there to really grieve, so we drank and ordered food. I dreaded the elongated conversations about how great he was. About how unfortunate it was that his life was cut short. I wondered why we felt the need to recycle the same sentences so much. If silence made its presence felt for one full second, it would immediately be broken by a “He was a great man, and he raised great kids”. I felt the misery of his death even greater when we talked about this. Still I put on a face of thoughtfulness and responded with “Sure was. We were lucky to have such a great father”.

His funeral was held at a golf course where the signs of summer warmth finally began to take shape. Golf courses in Alberta are where you can find the greenest grass that the province has to offer. I gave a speech about a time he got mad at me and my friends for smoking weed and waking him up. I avoided eye contact with anyone as I was on stage, afraid of meeting their pity.

My cousin worked at that golf course and she gave us access to the driving range. The entire family lined up and began striking balls into the open field where the sun hovered behind the spruce trees. The shadows displayed pretty, scattered patterns of the branches in the bright green grass. The golf course employees scooped up the graveyard of balls in the range and I wondered if they resented us for dirtying their already closed and tidied driving range. I imagined myself in their shoes and I thought I’d be mad. I longed to be the one that was mad. The one that was having to work a longer shift due to the celebrations of a life. I didn’t want to have to celebrate life if it meant one had to be lost. The funeral wrapped up in a blur. I was drunk and ready for bed, unknowing of what life would become in the coming days, weeks, years. In all that was unknown, the one thing I knew for certain was that life would be different.

I returned to my job at a cafe in Calgary a few days after the funeral. I grew a little nervous about facing my co-workers. I dreaded their looks of pity as I explained where I’d been for the past two weeks. To my surprise, when I arrived and began speaking with them I didn’t feel anxious at all. I simply passed through the conversations as if it were through a third person and I felt nothing at all. My co-worker asked me “How's your grandpa?”. I looked at him with an expressionless face and responded, “It was my dad. He died”.

I tried to enjoy the final passing month of summer as much as I could. I found myself regularly sitting at a part of the Bow river where the waves flowed wildly. Their splashing whites nearly resembled those of rapids. Friends and I would immerse ourselves in the cold, powerful river by descending from a concrete structure. The heat of the sun could be felt absorbed into the concrete. As we slid our tender feet into the water we felt the textural contrast from hot concrete to slimy concrete. We slipped ourselves in and together we rode down the current, treading water the entire time. Towards the end of the stream as our bodies grew tired, we could each feel our sagging bottoms gliding gently over the rocks. Sometimes it was not so gentle and our tailbones would slam against the rocks uncomfortably hard. When we’d reach the end of the rapids the water would open up a little into a calmer stream and we’d swim against its current towards land. Those of us who had made it to the rocks already laughed at the others who struggled against the force of the river. As we slipped further down the stream our arms plunged forward into the cool waters and fought towards the edge of land. When we reached the land we’d sunbath on the rocks and indulge in cigarettes and beer. The moving smiles that bounced from one friend's face to another brought me some temporary relief. I watched with my eyes squinted into the direction of the sun as a small family brought their kids into the river. The mother was standing at the top of the rapids, balancing herself against the concrete. She passed the kids in their life jackets down the current towards their father who stood at the bottom and the kids who must have been no older than 8 were laughing joyously, showing expressions of both excitement and a slight fear. It turned out that the fear they showed in those youthful little eyes was justified. Both myself and my friends were too distracted by our abuse of substances to notice the log that was upstream. It trudged through the chaotic, splashing waves with a force that looked unstoppable when it hit the mother in the back as she held her youngest looking child in her arms. The log sent her below the river's surface. The child went careening into rocks. The father stood at the bottom of the rapids with his other child, unknowing that the rapids were hurtling his wife and child down the river towards him. He looked up and realized his wife no longer stood at the top of the rapids. He squinted up towards the top and he saw his son in his bright orange life jacket being tossed towards him by the powerful waves as well as a heavyset log with each end poking in and out of the waves like a hazardous teeter totter. The father caught the boy in his arms and found that he was unconscious with a bloody gash on his head. Each of us who were resting on the rocks began to clue in to what happened when we saw the bloodied child and the log pounding its way through the waves. We swam out to help the father bring the children to shore. It was there on the rocks, with paramedics arriving where we saw the child take his last breath. We each stared into that battered, dead young face, unaware if it was real or just a terrible dream. I felt the boy's cold wet skin and I immediately felt a familiarity with death. The boy's face had that same helplessness I’d grown so used to seeing. Suddenly the boy looked aged and wrinkled, his mouth crusted from breathing through it for so long. The wailing bellows of the grieving father echoed through my ears. I heard my mothers cry screeching through the air as an airplane flew overhead and suddenly I was back in that room in the hospice. The cold skin felt just like my fathers and the tears that dripped down my face felt warm and heavy, just like they had then. I realized then how it must have felt for that father to hold his dying child in one arm and the alive but crying child in his other arm, balancing both of their grievances without the help of his wife, who was lost somewhere in the unknown. When I looked into his tears that splashed against the rock, I thought of my mother.

A search team was sent through the river waters for the wife and she was found, washed into a river dam, 5 kilometres downstream.

In the fall I spent most of my time in Calgary drinking and smoking at the bungalow. At times that little house surrounded by concrete could feel like a safe haven. Inside of it, I’d indulge in as many substances as I could get my hands on without leaving the safety of the house. I took a mouthful of mushrooms in the disguise of a peanut butter and jam sandwich. I sat on the porch waiting for the effects to take place, for that familiar feeling of serenity to take over and to make things fuzzy. The sun was beginning to set and a fluorescent orange sky was displaying itself prettily on the horizon. The long strident clouds shot themselves through the warm air and the atmosphere was taking me in with the warmth of fresh baked bread. Despite the fantastic display, I felt worried. I felt the anxiety of the summer's events building up inside me. I moved inside to the house and took off all of my clothes. My body covered itself in cold sweats. My mind was dizzied and I could feel myself slipping out of consciousness. A dark vignette began circulating in my line of vision and soon darkness engulfed it entirely.

I woke up covered in vomit. I stood up quickly, entirely discombobulated and unsure of what just happened. The vomit dripped off of my face and splattered the floor. I stumbled into the washroom and began to rinse my face. As I looked into the mirror, still dazed and barely conscious, I saw the eyes of the man who’d tried to break in. I could remember so clearly the way his eyes looked back at me in that pleading way. They looked as though they’d so badly needed to be let in. As though breaking into that tiny little bungalow was their only hope for survival. I shook the images from my head and hopped into the shower.

I had just stepped out of the shower when I heard a knock at the side door. I walked over to it, wrapped in a towel from the waist down. When I opened it no one was there but the eerie, empty night. I was just about to close the door when I looked down to see a jade plant placed perfectly in the middle of the step. I brought it in and inspected it closer. There was no note or any sign of it being a gift. Half of the leaves were browning quite badly and it had overgrown the size of its pot. I brought it into the light of the lamp and I began to see how much life it had left. I plucked the browning leaves and repotted it. Sure enough, despite its bareness, despite being worn out from life's tribulations, it looked reborn and ready to move on from its turbulent past and embrace its new home.

About the Creator

Neil Jefferies

Writer from Canada.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.