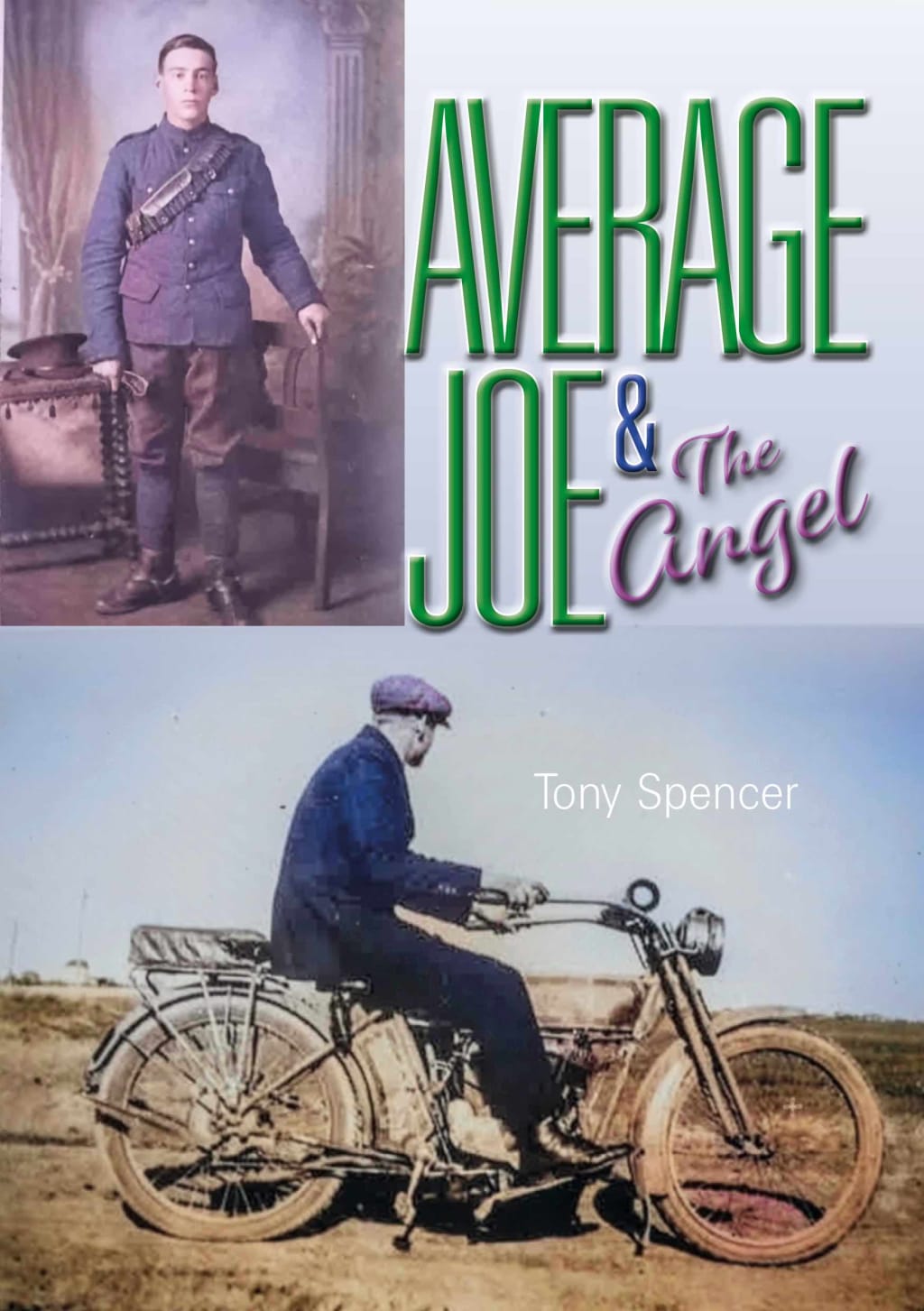

Average Joe & The Angel

Joe thought he was less than average

Prologue

Anjelica Harris narrates

I was late. I had flown in direct from Washington DC, leaving at first light and landed in Conrad, MT, mid morning. I called a cab which got me to the church almost in time, which was completely packed, with every single seat taken for the funeral service. That was only to be expected, of course, Joe Harris was always the most popular man in town, and everybody in this close-knit community wanted to see him off on his final journey.

I squeezed into the back of the church. It was standing room only. A few of the older people standing at the back recognised me and nodded to me silently, faces grim and impassive. The service had already started and there was no way I was going to disturb everyone by trying to make my way down to the front pew.

A couple to one side of me, standing behind the very last pew, moved closer together to allow me room to stand beside them so I could see Joe’s coffin in pride of place from where I stood.

The tall, broad man, dark tanned and handsome, black hair cropped short, resplendent in the dark blue dress uniform of a full colonel in the USAF, carried his hat and a single sheet of paper up to the church pulpit. He placed his hat and the paper on the sloping surface and looked up at the congregation for the first time. His eyes were sad and moist, but he stood to attention and squared back his broad shoulders, cleared his throat and began speaking in a distinct and well-educated voice.

"I am going against the best advice my father Joe ever gave me, the day I graduated from flight school. 'Never volunteer for anything, son,' Papa said, 'and you'll get along just fine.' Well, no-one was gonna beat me to the chance of coming up here and telling you all how much I loved the wonderful man whose life we are celebrating today, my dear Papa, Joseph Harris.

"All of you gathered here today to pay your last respects knew Joe. Most of you remember me, too, but I've been so busy these last ten years or so that I have only made flying visits to see Papa on high days and holidays on the farm and rarely showed my face about town much before flying off again.

"Papa encouraged me to fly, taking me up in his crop duster before I could even walk, even before I could talk. He inspired me to make flying a career and now I'm proud to be a part of the US space program; even as I speak, my fellow officers are preparing for the biggest adventure in human history, flying to and landing Mankind on the Moon for the very first time. Proudly, those humans who will be first to walk on the moon will be Americans, but that achievement is for all mankind. Yet, even that history-making event ... it’s nothing at all compared to the loss to humanity of the man we are gathered here to say a fond final farewell to.

"Joseph William Harris was born a long ways from us here in Conrad, Montana; he was from another small country town, Sittingbourne in Kent, England, born in 1887. He came here with our beloved Granny Harris and his sister when he was 10 years old, after his father died in a stone quarry accident. Granny's brother already had a farm here in Pondera County, and my great uncle paid their sea passage and train fare to bring them here where they could settle and thrive.

"Joe was a bright boy at school and he earned a place in college doing an agricultural degree before later qualifying and working as an electrician, the farm being then worked by his uncle and cousins. He was independently minded and wanted to strike out in business on his own rather than be another farm hand. He didn’t want to be an average anything.

"He became a US citizen in 1906. But he still felt he had strong ties with the old country of his birth and, when war was declared in Europe in 1914, Papa drove over the border and up to Calgary and joined the Canadian infantry, signed up on a Short Attestation Form for the duration of the war that was supposed to end all wars. It was a shock to Granny and even more devastating to his fiancée, you may remember High School Vice Principal MaryBeth Chambers, well she was his girl MaryBeth Johansson at the time, Papa told me. When he spoke about the past he said he had no regrets at all, he felt that he did his duty.

"He was considered an above average candidate by the Canadian Army recruiting office, because of his two college degrees, and was sent on a short officer training course and by April 1915 he was in the Flanders trenches, commissioned as a second lieutenant. He never talked about those times to us kids, I think he lost a lot of friends in those terrible trenches.

“In 1916 Papa transferred to the Royal Air Corps, sent for training in Egypt and flying a variety of airplanes, which led to recon missions and sorties back in France. He talked about those times all the time, he was never happier than when he was in the air. He crashed twice, bringing his plane to a landing those first two times without harm to himself, but he was third time unlucky in 1917, ironically, just a few weeks after the US joined the war against Germany. His plane was shot down and he lost his right leg just below the knee in the resulting prang and, after recovering in hospital in England, was shipped back home to Montana early in 1918.

“So there he was, Captain Joe Harris, DFC, DCM, age 31, with both his cousins killed in the war in France and his uncle struggling with running the farm on his own. Papa had no choice but to give up his ambitions of building things and take over the farm and work it with his Uncle, especially after his Aunt died of the ’flu that year. His fiancée MaryBeth Johansson had waited until he came home from the war but decided, after seeing his injuries, that she'd marry hardware store manager Ted Chambers instead.

“Papa found horse riding uncomfortable with only one leg and he couldn't drive either the truck or the tractor that was then on the farm. He bought a motorcycle, which had a hand gear lever, and a sidecar. It was more comfortable and he said it made him independent, which was always important to him.

"His uncle died in 1929 after a short sudden illness, leaving no Will, so Papa needed to take on help for the farm but he hadn't any money to pay them until probate which eventually settled the farm on Papa and Granny Harris as the only surviving next of kin. Then, in the new year of 1930, he met my Momma, Anjelica di Angelo, looking for work.

“I asked Momma how they met. She had hitched to Conrad to see her sister. But Aunt Connie had already left to go back to Chicago. Momma was a widow who had been married to an Italian immigrant Gianni di Angelo, who left home in Chicago looking for work in 1929 and never came back. She later found out that he was riding shotgun with some cousins on a bootleg spirit run from Canada which never got through, presumably shot and killed in a shoot-out with rival smugglers or the Royal Mounted Police. Heavily pregnant carrying me, Momma left Chicago, after she couldn't pay the rent, to find her cousin Connie who had moved to Seattle. But Conrad was as far as she got. A city girl in our little country town.

"The nurse here in Conrad told her that Papa was looking for farm workers and that being Friday she should wait in the general store and watch out for his motorcycle and sidecar. Momma didn't have any money so she wouldn't wait inside the warm store, she stood outside in the wind and snow. When she saw Joe pull up and limp to the steps and she looked into his clear blue eyes, she fainted."

At the back of the packed church, where I stood proudly listening to my son, I thought back to those days when I first came to this town and met Joe Harris.

Chapter 1

The first Friday in 1930

Anjelica Di Angelo narrating

I shivered as I waited outside the general store at the north end of the Main Street in the bleak city of Conrad, Montana in the middle of winter. I felt lightheaded as I pulled my thin jacket tight at the neck as I leaned back on the outside wooden wall of the store.

I would have given anything to have waited inside the warm shop, or bought a coffee and a sweet bread roll but I had no money, not one single penny. I tried to think back to when I last ate anything. It was just before I was beaten up and robbed of what little money and possessions I had, at the back of that truck stop, somewhere back along the road aways, I hadn't a clue where. I felt in some ways I was lucky. If I hadn't been nigh on eight months' heavy with child, the assault on me could have been worse.

Both men had said they'd, "a'raped ya if ya hadn't been such a fat colored cow".

The way they curved their cruel lips and their rough vindictive tongues around the 'colored' word, so full o' hate and malice, I'd felt that sentence more deeply than the punches that split my lip and blackened one of my eyes.

The nurse at the free hospital in Conrad who patched me up and checked the health of the baby, was a kindly local Indian woman, who said the baby was fine but added, "You be sure'n come by'n see me nex' week now, honey."

I said I couldn't be sure where I would be next week, I'd been on my way to stay with my cousin Connie, who'd moved to Seattle a year or two earlier, only to find out when I looked for her at her address, that Connie'd lost her job, had no prospects so far from home and left to go back to Chicago but a few days earlier.

Chicago was where I had travelled from two weeks previously and Connie and I probably crossed each other without being aware of the other somewhere along the road.

On the way back to Chicago I had used up most of my reserve cash and taken a train part of the way, but I hadn’t enough money to get very far, so I mostly walked and hitched rides. Then my last ride with a couple of white farm hands, one older and one younger, beat me up and dropped me off behind the next truck stop and robbed me of my last few dollars and my cardboard suitcase containing everything else that I owned. They even took the winter coat off my back.

"In order to stay here, I'd need work, 'n I cain't get no work lookin’ like this," I said to Nurse Annie, trying to keep my chin up and the building tears at bay. "An' it'll be worse in a month when the little one's born."

"What work you used to do, hon?" she asked.

"Before I was married I worked in a bank as a ledger clerk."

"Only one bank left open in Conrad now, hon, an' they ain’t doin' so well since the crash last year. Can you cook'n'clean, hon?"

"Well, household stuff, yeah, I guess."

"Tell you what, hon, it's Friday, the first Friday in January. You go wait by the gen'al store at the north end of this street and look out for a man on a motorcycle an' sidecar. He's alookin' for someone to live in and do chores for a few weeks, mebee even a couple o' months. His Ma had a fall an' sprained her ankle las' week. He always does his main grocery shop for dry and tinned goods on the first Friday of the month."

So I walked along that snowy main street as directed until I got to the store, the last one in the row, just dark fields beyond. The clock inside the store, that I could see from outside, said it was seven minutes past nine. The nurse had said that this Mr Harris, the man with the motor bike and sidecar, would be along between 9 and 10. I just hoped I hadn't missed him, either going in or coming out. I didn’t know what I would do if he had already taken someone on or didn’t like the look of me and with the baby's arrival so close.

I didn't go into the store to ask about Mr Harris, I knew how frightful I must look, the nurse, Annie Grey Feather had showed me my cut face and bruised eye, which was yellow under my brown skin, in the mirror. I leaned deeper into the wooden wall of the store under a short verandah, trying to shelter from the weather. I folded my arms into my chest above my 'bump', with my bare gloveless hands clenched under my armpits, locked my knees and closed my eyes for just a minute.

I awoke on my feet with a start. I heard the noisy motor bike like a muffled hammer banging on metal a while before I actually saw it. The snow was falling even more heavily now, with big and soft flakes, and somehow I felt a little warmer. Either that or I was so cold I couldn’t feel the cold any more.

Even the wind had died and the thick full flakes kissed the ground around the store, settling thick and even on the road. The sky was full of grey cloud, not a patch of blue anywhere. Although it was still the morning, it was almost as dark as night, the snow glistening in the glow from the electric lights from the store windows. The bike slowed, and turned, parking in front of the store, by the steps leading up to the sidewalk.

The rider wore a long leather coat, hat and goggles, his front completely covered in snow. Sudden silence reigned as the noisy engine cut out and he slowly climbed down. Because of the sidecar, he didn’t need to pull the bike onto its stand. Then he carefully made his way over old frozen ruts and fresh snow until he reached the steps and rail up to the wooden sidewalk.

He was tall, I noticed, very thin and walked with a pronounced limp, favoring his right leg. Then he removed his goggles and shook off the snow from his coat into the street. He climbed the five steps one at a time, left foot first and dragging his right after, then leading with his left again. When he reached the top, he lifted his face, seeing me for the first time in the shadows, he was lit up with the warm light from the store. He had the clearest, most startling blue eyes I'd ever seen on a man, it was how I imagined a clear mountain pool would look.

I stepped forward, but I was stiff and my legs felt as wobbly as jello, "Mr Harris? Excuse me, but Nurse Annie said ..."

Then I felt everything slip away from me and I crumbled to the ground, the last thing I heard was an English accent saying, "Oh, my Lord!"

***

When I awoke I was in a warm bed, the first I'd slept in for over two weeks. The starched linen sheets felt smooth and smelt fresh and clean. It was dark in the room, other than the flickering glow from a fire grate in the wall to the right of the bed. I was lying on one side of a huge double bed. Feeling the other side with my hand I assured myself I was alone. I lifted my head an inch or two and looked around. All the corners of the room were in shadow, the only light came from the fire, but it was quiet, just the odd crackle from the burning logs.

So, it seemed like I was alone in the room, with no idea at all where I was. I laid my head back into the pillows again, looking up the wall behind me, where I could make out a crucifix was hung above the bed. I couldn’t just lay there, I needed to know where I was, so sat up again stiffly. The first thing I noticed was that my clothing had been removed completely and I was wearing nothing but a cotton nightshirt. A couple of extra pillows were on the bed beside me and I tried to pull one behind me for more comfort sitting up, but my shoulder ached and I winced.

I heard a knock on the door at the end of the room and the tall, thin man with the blue eyes came in, carrying a tray, with a steaming cup on it. I recalled asking him earlier if his name was Mr Harris and, if so, I was supposed to see him about a job for a few weeks, while his mother was incapacitated. Before I could say anything, he spoke first, in that same English accent.

"Hallo," he said, "How are you feeling?"

"Er, my shoulder's sore, and I'm a bit woozy, I've got a headache, too."

"Well, that's about right, Ma'am," he said, "you cracked your head as you fell, an' Ma said you may have a bruise on your shoulder that you fell on."

"Are you Mr Harris?"

"I am, most assuredly, Ma'am," he replied.

"Did you undress me and put me abed, Mr Harris, or your Ma?"

"Ma's in a wheel chair at the minute, Ma'am, so I undressed you, put on your nightdress, an' carried you up here, but don't worry, I had my eyes closed the whole time, followin' Ma's explicit directions," he smiled, "I mighta peeped to get my bearin's but only for a second at most, Ma'am."

I didn't know what to say to that. He had a nice smile and what I had supposed had once been a handsome face but, by the light from the fire, I could see now that he had terrible scars on his left temple and cheek, and the top of his left ear was missing. I had only seen him from his right side before, outside the store.

"Sorry, I didn't mean to embarrass you, Ma'am, an' I never saw nothing, honestly. I have this habit of trying to be funny and failing more often than otherwise. Ma finds my sense o' humour ... wearing ... at best sometimes, and she's supposed to be my supportive mother!"

He set the tray down on the bedside table and leaned across me to grab the extra pillows. He smelled sweetly, I thought, the soft earthiness of meadow hay alongside the sharp scent of fresh soap.

I squirmed wondering, with some apprehension, how I smelt. I didn't want to upset myself any more than how I felt already by breathing in too deeply. I had tried to scrub myself clean back at that truck stop, after I had been attacked, but the water was cold and the soap hard and almost insoluble. My travelling clothes hadn't been washed in two weeks, I was all too aware, and hadn't any underwear to change into for the last three days, and all my other clothes had been stolen by my attackers.

He eased me up firmly, gently and propped me up with the pillows. Then he sat on the edge of the bed and passed me the cup, full of hot sweet and creamy milk.

"I'm Joe Harris, Mrs di Angelo. I fetched Nurse Carol to see you during yesterday afternoon. She looked you over although you was out like a light. She said you was just exhausted and malnourished. Rest assured your baby's fine, and I'm under orders to collect Nurse Carol or Annie just as soon as your time comes."

"Oh, I can't possibly stay here, Mr Harris I was just hoping you had some day work –"

"Nonsense, there's no need to go. In fact, you can’t actually leave now, it is snowing crazy at the minute. Where are you lodging? I can go in the bike and get your stuff if I'm quick before we get cut off by the drifts."

"I don't have nowhere, Mr Harris –"

"Joe, please.”

"Er, Joe. I arrived here yesterday, after finding my sister's moved back to Chicago on Monday and I had my suitcase stolen on Wednesday, hence my bruises."

"Well, in that case you can stay here until you are well."

"But –"

"But nothing, Ma'am."

"I need to find work, I have no money."

"There's work in our farm dairy here when you're up and well, an' Ma needs help around the house too. She bust her ankle a couple o' weeks ago and ain't too mobile at the moment. Now, drink up that hot milk, there's a warm robe here to wear. When you're ready, come downstairs into the kitchen for breakfast. When did you last eat?"

"Wednesday, I think?"

"Well, it's Saturday morning. You need to keep you and that baby well fed. The nurse was very insistent on that. Now, do you need a hand gettin' out o' bed, or can you manage, Ma'am?"

"I think I can manage." I said, "and I think if you want me to call you Joe, you should call me Anjelica or Anjie."

"Well, try and get up, Angel, I'll hold the robe open for you."

I found that I had virtually no strength in my arm and he had to help me get down from the high cast iron bed. I also had to lean on him as he helped me down the stairs.

***

The woman of the house, that I later came to regard fondly as Granny Harris, was in the kitchen, a big heavy woman, sitting at the table in her wheelchair. She made me welcome and laughed all the while as Joe kept feeding me French toast, bacon, eggs, pancakes and more toast. And glasses of fresh milk and a cup of tea. Ashamed to admit it, even at my age, but I sat there and ate like a pig until at last my appetite was satisfied and Joe couldn’t force another single morsel on me.

"So what brung you to Conrad?" Granny Harris asked me.

"My husband was killed last year in Canada," I said, "Gianni told me he was looking for laboring work in Canada, but he had lied to me. His sister-in-law came around after he had been gone a week and told me that he was with his brother, three cousins and a drifter and they were attempting to smuggle barrels of whiskey and gin into the US from Canada, only they ran into a rival gang of smugglers and in the shoot-out, all but the drifter were killed, shot dead and their truck and goods taken. My sister-in-law and her widowed cousins helped me out with food and the rent for a little while but they had lost their menfolk and source of income too. My company laid me off about the same time I heard Gianni was dead. The money dried up and I couldn’t make the rent no more."

"Oh you poor hen," Mrs Harris said in sympathy.

"I wrote to my cousin Connie a month ago and she said to come on out to Seattle where there was plenty of work in my line. But it took me two weeks to get there, part by train, part hitching, and the greater part walking. When I got to her address in Seattle, I found she had lost her job a couple of weeks ago when her company went bust and she had already returned to Chicago. She probably wrote me but I'd already left on my journey. I didn’t know anyone there and had to turn back and this is as far as I got after I was attacked and the last of my money and possessions was stole."

"What work you used to do, honey?" Granny Harris asked.

"I worked in a bank as a ledger clerk in Chicago for six years, but they were cutting staff last year and when I started to show with the baby they sacked me."

"Maybe you could help out here by looking at Joe's books for the farm. His uncle, my brother, died suddenly of heart failure last year and he used to file the tax returns for the farm and our personal tax forms. Joe's done his best with the books this year but he can never get them damn figures to balance right."

"Yeah, sure, I'll look them over." I said, as I was happy to help. It's just that after all that food, I felt really sleepy again.

But Granny Harris could see that. "Hey, Joe, honey, see Anjelica gets back up to bed for a couple more hours, she's almost out on her feet, the poor sweetheart."

"Please call me Anjie," I said, "Everyone does."

"I'd call you Angel," Joe said almost too quietly for me to hear as he helped me up the stairs, but I heard him all right.

Chapter 2

1969

Joey Harris continues his eulogy

I asked Momma how they met. She was a heavily pregnant widow, Anjelica di Angelo, who hitched to Conrad to stay with her sister. But Aunt Connie had already left to go back to Chicago. The hospital nurse told her that Papa was looking for dairy workers and that being Friday she should wait in the general store and watch out for his motorcycle and sidecar. She didn't have any money left and stubborn as she is, she wouldn't wait in the warm store, she stood outside in the wind and snow. When she saw Joe pull up and limp to the steps, she looked into his eyes and fainted. It's all right, folks, she was carrying me inside her and I turned out fine!

When she woke, she found herself in bed at the farm. I came along a couple of weeks later and soon Momma became Papa's right hand. She had worked in a bank, before she married my biological father, and she soon sorted out the farm books. Papa was certainly no fool, but paperwork was his blind spot and Momma naturally filled in that gap. He didn't think he could afford to pay for farm hands to help, especially since the dairy here in the city had gone bust and his milk was going to waste. But Momma found out about Granny Harris's brother's nest egg in the bank, put away for a rainy day.

Well, she told him straight, 'Joe, it's sure raining cats and dogs on you now!'

She set up a meeting with the local bank which had foreclosed on the dairy. They had no buyers for the business, nor any residual money in the dairy’s accounts to clean up the milk which had gone sour and was stinking out Main Street, so Momma set up Papa to buy the place lock, stock and barrel for a dollar. She organised staff for clean-up, and to staff it, wrote to all the old suppliers and customers and new ones and they soon had the dairy back in full production. They took on more workers at the farm and they were soon making serious money.

The same bank had a branch 150 miles away that had foreclosed on a crop dusting business, with three planes, spare parts, and several trucks including a fuel tanker. They asked Momma if they thought Papa with his wartime flying experience might take the business off their hands. Momma drove us down to the airfield to look them over. Papa again bought that company lock, stock and barrel for a handful of bucks. On our second trip down, Papa flew one plane back with Momma strapped in holding me in her arms. My first flight in an open aircraft and I was just a few weeks old, no wonder I took to flying like a fish to water! Papa had already prepared a field close to the house as the home airfield and arranged for a new barn raised over the weekend to be used as a hangar. The next trip he had some of the men drive back the tanker and other trucks, filled with barrels and drums of goodness knew what spraying chemicals. He even brought back Old Ernie Peterson, the aircraft engineer who managed to keep those World War One veteran planes in the air for the previous ten years. Old Ernie taught me everything mechanical about those planes, and he sure helped Papa keep those planes going for many years.

I learned how to fly from Papa in those old planes, even Momma learned to fly and she was out crop dusting during busy times as well as catching up with the dairy management and farm books. Soon, Papa, who never lacked for ideas, opened a milk bar in the town, where all my school friends hung out; for a long while it was the only place in town that sold ice cream and sodas.

It was a couple of years later that Momma got depositions from her husband's relatives to declare that he and five other family members were bringing three trucks over from Canada, ladened with spirits to beat the Prohibition, and believed killed, so she was free to marry Papa, who was still a bachelor in his early forties. And Papa adopted me as his son.

Chapter 3

Angel casting her mind back to April 1936

Anjelica Harris

Listening to Joey talk about those old days, I remembered that I had fond memories of that old dairy and the Milk Bar which was opened up in the front of the dairy in Main Street. We made small experimental batches of ice cream in the dairy and we needed somewhere to sell it. That milk and soda bar turned out to be a goldmine almost immediately and was the place to be seen in town from 1932 onwards.

Thinking about Joey and Joe, took me back to two events that changed my life in 1936.

We used to start early morning and finish early at the dairy, no shift working around the clock like nowadays. As the last one to leave the dairy office in mid-afternoon on a sunny spring morning, I, Anjie Harris, nee di Angelo, locked up the Conrad Dairy on Jefferson Street and drove my new Ford sedan down to the elementary school to collect my son Joe Junior. We were living well, working hard of course, but we felt we were building something for the future.

I couldn't stop smiling that spring day, but Junior was so full of what he had learned during the day. He was such a sweet kid, beautiful too, his looks taking after his father Gianni more than me. His skin was not as dark as mine, but with his straight black hair and square build, he had a strong Mediterranean look about him that I knew would drive the local girls wild in ten more years or so. Now, about to enter his fortieth year, Joey is a handsome man, still single as he seems ‘married’ to his service.

He was so full of what he was learning that Junior never even wondered why his Momma was even more cheerful than I usually was on that beautiful spring day. I loved my job running the financial side of the Conrad Dairy and loved my husband Joe Senior even more, so Joey Junior didn't notice anything out of the ordinary in my complete happiness.

Joe was still out spraying fertiliser from the air when we got back to the farm. Junior had a few barn chores to get through before washing up for dinner. Granny Harris was starting to lay the table and Junior took over the task, once Granny had checked the cleanliness of his hands and the state behind his ears, while she mashed the potatoes and stirred in the butter, we always had plenty of butter. Junior had heard the plane come in to land on the grass landing field up near the main road. While Junior was in the barn he knew his Papa would lock away the plane and the chemicals safely in the new hangar before he was home. There was water plumbed in at the hangar so he could wash up and change his clothes, isolating any chemical contamination to that one spot.

I had changed out of my office clothes but was still much more smartly dressed than I normally was in the evening, Junior may have thought if he noticed. Although the Harris farm was one of the best in the county, we were not accustomed to dressing for dinner like some more fancy folks did.

I waited until Joe parked his bike by the farmhouse before I headed him off from the kitchen to sit in the front porch for a quiet word with him before going inside together. Five minutes later we both burst through the kitchen to announce that Junior was going to have a brother or sister before the year was out.

It made me very happy, seeing all the smiles on my family's faces. My family. They were my family, but it had taken time to get here.

Joe always described himself as being born an 'Average Joe', when we were joking about, which we did pretty nearly all the time, we had a happy home life as Joe was always calm and collected, however excited Granny Harris, Joey or I got about anything. He would joke that with his missing half a leg and half of his ear, that he was now 'Less than Average'. But to me, Joe was a man better than any other man I knew up to then or since.

I was reminded of those first few weeks before my baby Joey was born, when I got to know Joe well and grew really fond of him in the shortest time, he was so attentive to me in the final weeks of my pregnancy so I knew he would be there for me when the first fruit of his loins was born. Back in those days there was no allowing the father to be present at the birth, it was the absolute domain of the midwife and they would only have womenfolk present. But Joe regarded Joey as "our" baby and they had a wonderful relationship that sometimes reduced me to joyful tears.

Back to when I arrived and was taken in by the Harrises, I was up and about the next day, with plenty of fresh food inside me from that first breakfast, plus the catching up on my sleep. I was full of energy and I revelled in how friendly the two Harris's, both mother and son, were towards me. I helped out around the house for two or three hours a day, and for the first week I spent those hours each day going through all of his farm day ledgers and boxful of receipts going back a couple of years.

His books weren’t so bad as he made out, but he missed off odd things, like cash paid for fuel and petty cash in general. Granny Harris confused him too with receipts that were mixed personal expenses, like housekeeping, and bills to do with farm business. A lot of the farm's customers were not paying invoices or only partly paying them in drips and drabs, so it was unsure which bills were paid and which were still outstanding. Joe had trouble chasing debts, he was just too nice a person to do what his uncle had had to do to get the knuckleheads to pay up their dues on time.

I wasn’t too nice at all when going about chasing overdue payments and we soon had payments rolling in without threatening legal action, the embarrassment of pointing out what was owed was usually enough for most customers and the bad customers were forced to take their custom elsewhere or knuckle down and pay up in advance. Sure, there were some bad debts, but mostly they were people who needed to continue trading with us, so for the more reliable customers we managed to arrange spread payments. Some folks were not able to settle for years, but we couldn’t let people starve and, in the long run, everyone got by, it was and still is that kind of friendly community.

The Harris family took me in as part of the family from the outset, loving Joey as one of them. They were from England and never seemed to have that inbuilt prejudice against anyone in terms of color that some country white people had. I was black, or half black through my slave grandma, bless her soul, so I was quite light skinned for a Negro, but working with the Harris's and dealing with them with their customers in Conrad, I never had no trouble with race. The area round about was all either white or native Indian. When we took on workers, about a quarter of them were Indian and Joe never put up with any racialism directed towards them, he treated everyone alike and the Indians loved working for us and loved Joe particularly as a fair and honest employer. I think they admired him too because he never let his disability get him down or hold him back from doing what he wanted to do, he’d just work a way around it.

Meeting with the bank to firm up on lines of credit and transferring balances to investment accounts, we discovered that the farm business already had investment accounts with money available that his uncle had put away that Joe knew nothing about. That and the interest that had accrued put him in a position that the farm could employ more labourers on the farm, invest in machinery at rock bottom prices and make his farm even more profitable.

The bank manager pointed out that the bank had foreclosed the dairy in town and were saddled with it, having no buyers, but they were willing to sell it for a dollar if the buyer would immediately clear it out, because the dairy was in Main Street opposite the bank and the smell of rotting milk was affecting the whole area.

That same day, Joe employed the fifty out of work ex-dairymen and women to come in and clean up the dairy and get it back up in production, taking in and selling what milk they could get from local farms and giving a lot of it away free to schools, the hospital and distributed free to the needy through the churches. Soon they had cream, yoghurt and cheese-making up and running and shipping out by train to an eager market in nearby towns and gradually further away.

Chapter 4, May 1936

Anjelica Di Angelo

The second major incident that happened in the spring of 1936, also started at the dairy. I was reconciling the April accounts ready for the following Monday’s board meeting. We had kept the dairy going as a separate concern from both the farm and the crop dusting businesses, so it could be sold off easier if we needed to. Anything over a dollar plus the clean-up costs were pure profit. But the dairy was going so well, especially with the new Milk Bar, that we kept it going, with just Joe, Granny Harris and myself as company secretary, on the board. The telephone on my desk rang, so I answered. It was Suzanne in Reception saying I had a visitor. I wasn’t expecting anyone, so I asked her who it was. The answer came back, “A Mister di Angelo is here to see you.”

The only di Angelo I knew was my late husband Gianni, who I understood was killed in 1929 in Canada, murdered with his only brother and cousins by rival bootleggers. I asked Suzanne to send him up to my office. I got up out of my chair and met him at the doorway. I couldn’t believe it! It was my Gianni, raised as if from the dead.

I pulled him into the office and, before I could stop him, he kissed me on the lips. It was like all the kisses I remembered, hot and passionate, and the last six years just melted away and I felt in my twenties again and still married to this man. Eventually he stopped his kissing and I was able to breathe.

"What happened to you, Gianni, your sister-in-law told me you and Georgio were shot dead in Canada?"

"We were all shot in a double-cross by a rival group of gin-runners who thought we was muscling into their business, including my brother, cousins and a friend of my brother's, Alberto Bianchi, a drifter from back east. They was all dead, me badly wounded and left for dead. I had a criminal record from before we married and faced a long jail term, so I swapped my papers with Alberto. I got five years instead of twenty."

"So when did you get out?" I asked.

"Two years ago."

"Two years ago? Why didn’t you come looking for me?"

"I’m lookin’ now, ain’t I?" he retorted, "I never knew where you was until your cousin Connie came into my club last week."

"Connie? My Connie?" I asked.

Joey always called her ‘Aunt Connie’ even though she was my cousin, so Joey assumed during his eulogy for Joe that she was my sister.

"Yeah, large as life, came in with a party of girls from where she works. Done up real nice she was. Boy, was she surprised to see me in the flesh!"

"Your club, is that where you work?"

"It’s my night club, Anj, I’m the boss. Doin’ real well too. Gotta nice apartment above it, too. Connie told me about the kid, Junior, so I got the second bedroom all done up nice for him."

"How did you manage to get a night club, you were locked up in prison for five years, right?"

"Yeah, but I kept my nose clean. I told the cops I was just an outta work hired hand, knew nobody, knows nothing about the organisation of the gin-runners. So when I gets out after doing my time I’m in with the bosses, one of the trusted few, so I get a good job managing a speakeasy that’s suddenly a goldmine when Prohibition gets lifted, so I’m doin’ so well the organisation lets me buy a 50-50 partnership, which means we are sittin’ pretty, sweetheart. So when Connie tells me where you are, I think, great, I’ll come and fetch you and my kid and bring you home. You’ll love it babe, we’re set up for life and really going places"

"But you were dead, everyone said so, and I have a life here now, Joey’s just started school and loves it here in the countryside. It’s all he’s ever known. And Gianni, I’m ... I’m married."

"Sure you are, you’re married to me. And if you like the countryside I’m a family man now so I can get us a place in the country. I go by the name ‘Johnny’ now, Johnny Bianchi, the ‘Di Angelo’ name was too hot. Hey, I don’t blame you for what you did to get by honey, shackin’ up with a hick farmer, you was all alone here. That was my fault, the smuggling went wrong and you was left holding the baby, really left holding the baby, my baby boy. But now I’m back and we belong together in the eyes of God. That marriage here in Hicksville don’ amount to a hill of beans, our marriage is the only one that counts. Besides, I want my kid back. When can I see him?"

"He’s at school, I’ll pick him up this afternoon."

"Great. Maybe I can take you out to lunch, you could show me the town, or I could show you my room at the hotel."

"I have to work, Gianni —"

"Johnny, Anj, remember I’m Johnny now. Can’t we pick the kid up now and go play catch in the park?"

"No, he’s got school, not kindergarten, he can’t just get up and go. And I can’t either, I have the monthly financial reports to finish."

"Hey, I understand business is business. What about lunch, huh? You need to eat and we need to catch up."

"I don’t normally go out to lunch, I bring a sandwich and work through so I can get off and pick up Joey."

"Joey? You didn’t name my first born after me?"

"No, I thought you’d died, Johnny, I named our baby Joseph Gianni Mario Di Angelo. But, I have to tell you, when I remarried and my husband adopted Joey, so he is now Joseph Gianni Mario Harris. And Joey calls Joe his Dad and Joe calls him Junior."

"Well, you’re not really married to this fagiolo, I married you first, in church before God and wit—"

"But Johnny, we had a death certificate, according to the authorities in Canada you were dead. You could’ve let me know."

"I was in prison, pretending to be someone else. All letters in and out were censored, so I couldn’t write you. Also. I didn’t know where you went when I was out looking for you. I thought you’d wait for me in Chicago. But no problem, I’m back now. I am a success, Anj, doing well enough that you will never have to go working in an office nine to five ever again. I will come back here in three hours and we’ll go pick up the bambino."

I couldn’t concentrate on the figures. Just the thought, my husband came back from the dead. I loved Joe, he was the best husband. But Gianni, Johnny as he wanted to be called, was my first boyfriend, we had known each other for a long time. And he had fought for me when we were kids and I was being bullied. Life for a half-caste Negro girl in Chicago was hard, even for someone with as light a skin as mine, and Italians then married only other Italians, so Gianni got into a lot of fights over me. He was my hero. I loved him, I had always loved him and now he was back, and my life here in this small town, I had to admit, was over.

I could tell that my Joey was not happy with Gianni. As soon as we collected him from the school, instead of letting me handle it, Gianni, sorry, ‘Johnny’, jumped straight in and told Joey he was his real father and that from now he’d be known as ‘Johnny Junior’ and live in the big city.

Joey tried to hide behind me, insisting that he already had a Daddy, the only Daddy he knew and he was Joey or Joey Junior, not any other nasty name that he didn’t want. He was clearly frightened but defiant.

For a moment I thought, he’s more Joe’s son that he could ever be Gianni’s. Even the set of his chin, even though it was an exact match of Gianni’s, was jutted out like Joe when he refused to budge an inch, like when I tried to stop trading with the farmer’s co-op because they were so far in debt a couple of years ago and he said they’d pay up eventually provided we didn’t kick them in the teeth. And they did and their smiles were still so intact that they turned into one of our best customers with the sweetest dairy milk you could taste; the Milk Bar was stocked almost exclusively with their cream and buttermilk.

"Look, sweetheart," I said to Joey, crouching down to his level, "we’ll have a long train ride into the city, you’ll have a nice room of your own and, if you don’t like it I can bring you back here to stay. Would that be all right?"

While Gianni, or "Johnny", as he now preferred to be known, went back to the hotel he'd stayed at for a couple of nights, to pack and meet us at the station, I went home to pick up clothes and stuff for Joey and me.

When we got back to the Harris farm, Joe was still out on the farm working. I packed a small suitcase with a couple of changes of clothing for Junior and me, told Granny Harris we were heading for the station as my first husband had come for me.

Chapter 5 1969

Joey Harris concludes his eulogy

"With Old Ernie keeping three crop dusters in the air, it was sure as eggs were eggs that I would fly with Papa as soon as I could sit upright on a sack of cornmeal so I could see out of the cockpit. So, it didn't take long before I was doing the flying while Papa operated the sprayer from the passenger seat in front. Momma, being the driving force she was in the family, was also solo flying planes, she learned to fly solo while I was still in diapers and she was a fine and careful flier. Yes sir, she certainly had Old Ernie fixing everything properly that was even slightly under regulation.

"As soon as the war against Japan was declared, followed by the declaration of war against Germany, Papa wanted to volunteer for the US Air Force. He was 55 but told the recruiting Sargent he was 42 and had been a captain in the British RFC. I think they realised he had lied about his age, but they put him on delivering new aircraft from factory to airfields all over the country for training, or flew them close to the ports that were sending them overseas for the invasion of Europe, D Day. He was often gone from home for weeks at a time, but never happier than when he was in the air. He hardly ever spoke about his First World War, but you couldn’t stop him talking about the Second.

I was only 12 when the war started, but you grow up real quick in war time. Momma had also joined up too, also volunteering to deliver airplanes from the factory to where ever they had to go. They both trained on a variety of aircraft from fighters to bombers and spent the next couple of years crisis-crossing the country, hardly ever meeting.

"Then in 1944 Papa flew bombers over the Atlantic in preparation for the D Day invasion of Europe. This was his first time back in his old country for eighteen years.

All through his life he used to tell us kids, and anyone else who was listening, or tried to heap praise on him, that he was just an Average Joe, doing his duty to the best he could. Well, we have packed out this church today to say say goodbye to a Joe who was son, husband, father, grandfather, colleague and friend and to us all ... he was anything but average."

Chapter 6 1969

Anjelica Harris narrating

I could see the tears roll down my Joey’s cheeks as he finished saying goodbye in front of all our family and friends to the only real father he knew. I felt the tears running down my cheeks, too.

The woman standing next to me put her arm around me. I knew her, by face if not name, but she knew me and she must’ve known Joe and loved him too. He had just so much to give, everybody loved Average Joe Harris.

The coffin was laid on the shoulders of eight sorrowful but proud men. I knew them all well, three of them were my children. When they drew near, Joey spotted me at the back of the church.

"Momma, you made it!"

"Yes, they tried to filibust us all night but we got the Farm Reform Act through the House and onto the Senate last night, and I flew up early this morning."

I fell in behind the coffin, with our daughters Jelly Fox and Molly Andrews and we walked out to the Harris family plot, where Joe’s mother and his uncle lay along with memorials to Joe’s brave cousins, lost in France while keeping the world free from imperial oppression.

Joe was a Justice of the Peace and a local Councilman, but he wasn’t really interested in politics, he was a working farmer, but he was concerned about farmers’ rights in Washington, so he urged me to serve in the House of Representatives for the State of Montana, which I did from 1969 to 1971, the second woman and the first person of color from my state to do so.

I almost left Conrad with Johnny and without Joey back in 1936. Joey flatly refused to go, folding his arms and planted his feet apart and holding onto Granny Harris in the kitchen. At the station my first husband Johnny Bianchi was disappointed hearing about me leaving Joey behind, but he needed to get us back to Chicago.

As soon as Joe reached the farmhouse and between them Joey and Granny Harris explained to him how I’d left with my first husband and how it came about that he was still alive, Joe jumped on his bike and rode hell for leather to the railway station.

Why the station? Johnny, the businessman and club owner from Chicago, was afraid of flying. Joe had me comfortable flying solo in all three of our planes, all very different models, within six months of bringing them home.

"Angel," Joe said at the station, as we stood there the three of us, the train calling all aboard’, "please don’t break up our family. I know you told Mum that your former criminal husband is now legit, but do you really know this man? Do you remember what life was like when you were his wife and how your life is now? Do you realise how many people are relying on you for their jobs, at the dairy, the farm, the small businesses and tradesmen in this town? Do you realise how much I would miss you? Granny would miss you and Joey, if he joined you would miss the only home he knows, and how you going away without him would tear Joey apart? And what about the baby?"

The baby! In all the excitement, I’d forgotten the baby, our baby, Joe’s baby inside me, due before Christmas. How could Gianni, Johnny make me forget my baby? Was I mad?

I looked at Johnny, clean-shaven, tall, dark and handsome, his black hair slick, in his smart double-breasted suit, sharp down to his patent leather shoes. The Windsor-knotted tie complemented his sharp silk shirt, diamond tie pin and matching diamond cuffs, his shirt cuffs being tugged by his soft, manicured hands as I looked him up and down, every inch the stylish businessman in his mid-30s.

Joe, on the other hand, his sandy-colored hair thinning and uncombed, he was of just above average height and wiry build, his worried face scarred by war and tanned by daily contact with the elements, in his late forties, his work dungarees freshly soiled and permanently stained by the toil of his labours, his thick cotton unbuttoned shirt frayed at the collar and cuffs, his working boots scuffed and caked with mud, his hat pulled from his head and screwed up in his calloused hands as he pleaded with me to reconsider.

I had kissed his scars nightly, lovingly, thanking him for doing his sacrifice and service for both his countries when they needed him. I was proud of him in company, an honest, decent, modest man, successful because people liked him, respected him, trusted him. I loved him for caring for me and loving me completely when only a couple of days before I met him I was dismissed as a ‘fat colored cow’. Joe had loved my son as if he was his very own. I loved him because he treated me with respect as an equal, in our businesses, in our home and in our bedroom. I loved him for his dedication to work, making us a team indispensable to the town. I loved his slow gentle smile and his passion for life. I loved him for loving me as much as I loved him.

I did love him, this man who insisted he was so average and yet was so much more than the sum of his parts. I loved this man who had been the real father to his son and would be the father of all fathers for the baby to come and any other babies to follow.

I smiled warmly at him, and he smiled back with that lovely smile of his.

I turned to Gianni, to apologise to him.

And I looked at Gianni closely again, the hazy mists and old feelings of memories which had affected my perception began clearing. His face was no longer handsome, but haughty and sneering, his eyes full of hate for this challenge to his wishes and expectations from this humble farmer.

"Go back to your farm, old man," Johnny snarled at Joe, "Anjelica’s mine again, she’s always been mine, and no hick farmer’s gonna take her away from me. When we’re settled at home, we’ll be back for my son Johnny Junior, and there ain’t nothin’ you can do to stop me if you know what’s good for you."

With that, he undid his jacket with his left hand, revealing a handgun in a shoulder holster which he reached for with his right hand, after letting go of my arm.

"No!" I yelled at Gianni.

By the time he had his hand on the gun, Joe was onto him. I never saw him move so fast, except in the stables when instinct told him a horse was about to kick him or Joey. He stamped on Gianni’s slim shiny shoe with his left foot, grabbed Gianni’s hand and holsters with his strong work-hardened hands so neither hand nor gun were going anywhere, and lifted his right knee into Gianni’s groin. Then he held him upright even though Gianni’s legs had completely turned to jello.

Joe asked if I was all right, all the while looking into Gianni’s eyes. I nodded and said, "Yes, are you all right, honey?”

"Yes, I’m fine," he replied, still locked on my first husband’s eyes.

"I’m so sorry, Joe, I was just confused. I love you both but I really only loved Gianni as a boy, a kid. As a grown up, well he never really grew up, you know? But we were married for better for worse, even though most of our marriage was for worse. I knew he cheated on me, I know he would always cheat on me. Only, because you and I were so in love I could forget what an ass he was and just remember the few good things, like saving me from bullies, and ignored the fact they he was a bully too. When he turned up today ... without you here to ground me ... I was ... lost, lost in a fantasy that never really existed, could never exist. Will you forgive me honey? Could you forgive me?"

"We’ll talk when we get home. I can see Charlie has called the police ..."

I could also see that the Station Manager was on his phone in his office, in fact I could even hear the police bell, the police station was only two minutes away. Briefly I recall Gianni being charged not with drawing a concealed weapon, which is permitted in our state, even in town, but it was an illegal weapon with all the serial numbers filed off that he had drawn in anger and witnesses waiting for the 8 o’clock train testified they thought he drew the weapon with intent. At the trial, his name and history was revealed and, after a three-year jail time in Montana, he was extradited to Canada where he was re-sentenced for the shootout in 1929, taking into account previous convictions and sentenced to a further 10 years. The illegal gun he carried was about twenty years old and responsible for at least twelve unsolved murders in Chicago since 1925, four of them in the two years he had lived there since his release, however, there was no evidence how long he had held the weapon. Gianni was released in 1942 but was gunned down shortly after returning to Chicago. Joey only saw him the once and Joe and I only saw him again briefly in court, during Joe’s testimony.

Chapter 7 1990

Anjelica Harris narrating

I rarely think of that day in 1936 any more. Most of my memories are pleasant ones of my life with Joe, my much better than average partner in life.

"Jelly" Anjelica Elizabeth Harris was born just before Christmas 1936. She married local boy Aaron Fox in 1958, and gave us three beautiful grandchildren. "Molly" Mary Ellen Harris followed in 1938. She married Harry Andrews in 1961 and went one better, giving us four grandchildren. "Bobbie-Gee" Robert George Harris lived from 1940-2003, and took over the farm as dairy/arable farmer; Bobbie-Gee was a quiet, shy man who never married but was always smiling as loving favorite uncle to all the children in the family. "Hughie" Hugh Browne Harris, born 1944, took over the dairy and now his only son, another Joe Harris, runs it.

Joe and I delivered new combat aircraft for as long as we could during the war, relying heavily on Granny Harris to look after the homestead as we traversed the skies in our lonely flights, helping the war effort the best way we could. That came to an end in1944 when "Hughie" was born and I had to stay home, by then Granny was 75 and five kids ages 14 down to zero would be too much for her. The wonderfully kind and generous Granny Harris passed on in 1953 and is still missed every day of our lives.

I only entered politics for the benefit of local issues and then only served two years in the House, and glad to get away from there at the end of my two-year term. My biggest regret was that I had to dash away from Joe’s deathbed to debate in Washington and vote on a bill dear to our hearts and missed the first few minutes of his funeral service. Those 39 years we spent together were wonderful years and losing my suitcase and being rescued by my much more than average real life hero was the best thing that ever happened to me.

Epilogue

Mrs Anjelica Harris died in 1996 at the farm which had been her home for 66 years, surrounded by her children, grandchildren and great grandchildren, too many to count as they were all blessed with the energy of their beloved forebears.

Colonel Joey Harris never went into space, but he remained part of the training program for pilots at Houston until he retired. He died in 2009 a venerable old man of 79 who had no end of wonderful stories to tell about early space exploration; he had three children and seven grandchildren.

The end

Please note: this story is pure fiction, none of these people really exist, it is a story told to entertain me and anyone prepared to tarry a while alongside me. A person of colour (sorry, I’m English and use my original mother tongue when I can) has never represented Montana in the House of Representatives. A woman, Jeanette Rankin (1880-1973), did represent Montana twice, in 1917-19 and 1941-43 for the Republicans, a lifelong suffragette campaigner and pacifist, she voted against declaring war on Germany in 1917 and was the only member of Congress to vote against declaring war on Japan in 1941; she was instrumental in introducing the 19th Congressional Amendment granting universal voting rights to women and was politically active for over 60 years.

Although the story may appear to align itself to the present Black Lives Matter movement, the story and all of its plot points were actually determined 5 years ago when I started the story, and dropped it half-finished back then, using some of the plot and character details for new characters for a different novel completed between 2016 and 2019. It was a pleasure to return to the plot and complete it during the first long COVID-19 lockdown and presented to you now in its completed form.

However, my sentiments that there is only one human race and we should learn to live in harmony and respect, whatever god we admit to and to whatever tribal sensibilities we might prefer to live by, that shouldn’t affect our respect for the liberty and fraternity of us all in the single community that is mankind.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.