A Sigil of Seeds

A tree, twenty-six letters, and forever

“Careful,” Grandma Baer said. “If you slice your thumb open, I won’t be able to drive you to the hospital. Tom’s got the truck.”

My next cut was cleaner. A smooth slice across the curve of the pear, exposing a tease of colorless flesh.

“Now pry that open. Be sure you’re from the pulling bottom to the top so the seeds don’t scatter. They’re no good to you if you can't find them in the grass.”

It sounded like her voice was in my skull. My brother, Tommy, had gotten special headphones to wear on his bike so he could still hear the traffic creeping up behind him. They sat slightly in front of his ears, pressed against the bone there, and vibrated sound into his head. This was what Grandma Baer’s voice was like: gentle but obtrusive, the slightest press against my ear canal as if to say, I could live here I’d I wanted to and there’s not a damn thing you could do about it.

I pried open the pear belly, agonizingly slow. I’d never heard the end of it if I lost this batch and had to wait another year for the first fruit to flourish. Three seeds popped onto my hand, one after another, just as she said they would. They wouldn’t have dared do anything else. The Baer Bear, Tommy called her.

She smiled at me, expectant. I forced a grin.

“That’s awesome, grandma.”

Her smile disappeared.

“Don’t patronize me, Kirsten. You won’t find it funny when Fawn Henderson is happily married with a big round belly and you’re still sweeping up your grandfather's store for allowance to go to the cinema.”

I bit my tongue. She didn’t know the first thing about what I’d find funny. I found grandpa funny, for example; his jokes about fish and folks and fellas were the highlight of my day. And frankly, going to the movies by myself with a pocket full of cash for fresh popcorn sounded a hell of a lot better than waddling around a house barefoot and preggo before twenty. (Also, who called movies the cinema anyway?)

But then I thought of Flawless Fawn, carving out her flawless future from the stone of a peach. Or Clarissa, her best friend from her church group, sealing her fate with a Granny Smith core. I thought of those girls and their immutable chances at happiness and my competitive streak flared. I didn’t want what they had but I wanted that they had it. Yeah, it didn’t make perfect sense to me either.

It should have been easiest for me. The Baer women had the best fruit for fixing futures: sweet, ripe, crisp Bartlett pears. A whole orchard of them, waiting to be plucked and plundered. Three seeds was all it took - one for each letter of my beloved's name.

The Hendersons had it the worst. In their tradition, the girls have to hold the peach pit in their mouths until their tongues bleed, then press the ruined flesh to a clean sheet of parchment and read the name of their future lover in bloody hieroglyphics.

Clarissa's family was slightly more civilized, if less accurate. They would toss the core onto an ancient board covered with letters like a Ouija board varnished with centuries of apple slime. Most boys in Peckinpah County had J names or M names, though, so the only interesting thing about that process was guessing Matts versus Marvins, Jimmys versus Jakes.

The Baers are true mystics, though. On our birthdays, anytime between ages fifteen and nineteen, we pressed seeds, still fresh from the womb of the pears, onto our foreheads, forming a triangle. Then, we’d start reciting the alphabet until, seed by seed, each one fell. This was how we learned the initials of our future betrothed. We’d never missed the mark in a hundred generations. My grandparents had done it and had found each other. Tommy had done it, and now he was engaged to a girl he’d met his first week at college.

Today was my eighteenth. I’d missed three chances before this—twice I had fallen ill the night before and was too sick to climb the branches and for my fruit.

Last year, I refused. I was already in love, I’d claimed. Cain Jessup had taken me to see a double feature of Kill Bill I and II at the Peckinpah County drive-in and I had thought, after licorice flavored kisses and a buttery grope in the front seat over the worn stick shift, that I would marry him someday. I was, of course, wrong.

The pear tree had not spoken yet.

Now, my grandmother forgot how to be gentle. She shoved my shoulders so I would sink, cross-legged, to the soft grass, sweet-scented, and gummy with wilted pear flesh. I pressed the seeds into my skin, trying to imagine each one covering the freckles I hated. First name, top. Middle name, right. Last name, left

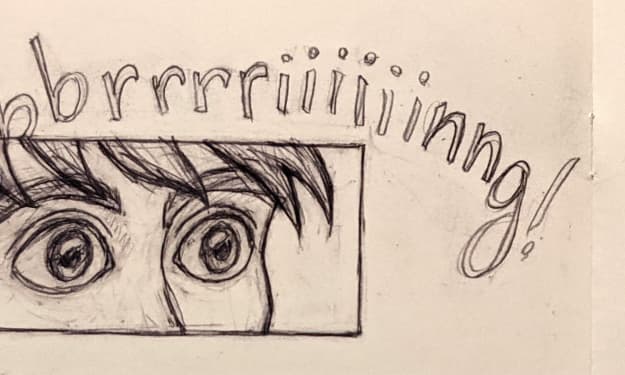

Then, I closed my eyes, focused on the birdsong around me, and recited, three times, the twenty-six letters that would seal my fate.

***

Grandma Baer hummed while she finished supper that night. I could hear her through the floorboards, her song winding through the slats under my feet. I wanted to stomp in response, arrhythmic and angry. I wanted her to know where she could stick her asinine superstitions; I wanted her to hear the petulance in my very toes.

X-Y-Z.

Those were my initials. My true love.

I snorted. What a joke. I’d waited two years and wasted a third for absolute nonsense. Fawn would ask on Monday, wincing over her sore tongue and dabbing it gingerly with an ice cube, the paper towel it was wrapped in growing soggy and leaving wet trails across her homework.

“Who’d you get stuck with, Kirsten?”

George, I’d want to tell her. George Gables. Her crush. Blond curls and bicep curls. Blue eyes and big lies. Georgie Porgie. But the lie would feel like mortar in my mouth and I’d have to tell her the truth: "No one," I’d say. "It didn’t work for me."

I could hear grandma full-on singing now, a thin warble that belied her sturdy frame. How could she be so cheerful when her plan had so utterly failed?

I wondered cruelly if she was happy that it hadn’t worked for me. The last person she had tried to pear seed before Tom and me had been my mom and look what had happened to her. Widowed at twenty-one. Dead by twenty-five. Leaving me, a squall of an infant, to be raised by grandparents who believed in bedtime at nine and marriage at nineteen.

I shoved my books off my bed so I could flop down, boneless. Maybe my flopping would have more of an effect downstairs than my stomping.

My yearbook fell open to the middle seam, a full spread of last year’s musical, South Pacific. In the middle of the photo, George and Fawn, the leads, mugging for the camera, their rouged cheeks looking puffy and wan under the bright lights. Behind them, two rows of lesser actors and then the scraggly stage crew, dressed in black, looming above the actors on the stage risers.

I reached to close the book but froze when I saw him. Taller than the rest, his black hair disappearing into the darkness of the curtains. Ave Zimmerman. Stage Crew. Lead light tech.

Best kisser ever.

I only knew this from a misguided adventure earlier in the summer at Beattie Greggs’s bonfire where even I was drawn, moth-like, to the literal flame in her back forty by the promise of music and mayhem and make-outs. We all passed around sweaty bottles of Boone’s Farm and took turns throwing up in the pines that encircled the Greggs’s property.

Early in the evening, Ave had grabbed my arm just before I’d tripped over someone’s abandoned Chuck Taylor’s and so, enticed by his chivalry, I’d applied some Baer magic to the spinning bottle in the self-same game, and charmed it to point toward his lanky frame.

He’d watched me for a long moment and then unfolded himself like origami and held out a hand to me, a sober gentleman among tipsy assholes, and kissed both corners of my mouth, whispering, “later” in the curve of my ear before depositing me back in the circle.

When later came, he’d not uttered a single word about my stale clove-scented breath as he’d kissed me and kissed me and kissed me to the crackle of the dying bonfire, the whistle of wind in the pines.

“What kind of name is Ave?” I’d asked, under the soft push of his chin.

“Nickname,” he’d rumbled into my mouth.

“Short for something?” I could barely think, let alone form words, but he needed to know I wanted him for more than his mouth in that moment.

“Xavier,” he’d said. “Xavier Yves Zimmerman.”

I’d forgotten. How could I have forgotten?

After that night, I’d ignored him at school. He wasn’t boyfriend material. Promposal material. He was a shadow, a ghost. He stayed underneath my skin, though. Colorless flesh under a crisp, tart exterior.

I draped myself over my bed and looked again. Xavier Zimmerman looked back at me. A three-dimensional stare from a two-dimensional page. I sat up. Alarmed. Elated. Enchanted. My blood felt sluggish in my veins.

My grandmother's song split in two as my grandfather came home and took up the harmony. They laughed together in the kitchen below me. Forty years paired. (Peared? Whatever we Baers called it.)

“Kirstin,” Grandpa boomed, “‘Dinner in ten. Shake a tail feather.”

“Be right down,” I called back. My voice sounded otherworldly.

My phone was charging on the nightstand, glowing with promise. I didn’t have his number but we followed each other on Instagram. I tapped to DM him; his dot was green: online now.

Hey, I typed, still feeling the press of the pear seeds on my forehead like a sigil. How do you feel about the cinema?

About the Creator

Maisie Krash

fiction writer, probably a witch

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.