Waterfalls

It's frightening, isn't it? How lucky you have to be to live in this world?

Once, when the boys were very little, I wanted to get a therapy dog for Dylan. That was after he ran away when he was four, making it nearly a half-mile from our house walking along a busy street in just a diaper until he was found by a nurse who called into 911 about the time that I did.

Therapy dogs cost a lot of money. $25,000 or so for a dog that would be trained to slow down Dylan, or help him keep calm, or maybe just root himself to the spot if Dylan tried to leave our yard. Dylan, of course, would be attached to the dog, and would go through life, or at least a significant chunk of his life, attached to the dog.

Instead, because therapy dogs cost $25,000 and because "GoFundMe" was in its infancy and because we were not lucky enough to catch the eye of William Shatner and have him retweet our equivalent of that one family's plea for Star Trek themed macaroni and cheese, we didn't get a therapy dog.

When you stop to consider just how much in our life relies on sheer luck -- not just the wildly good things like getting picked for Contestants' Row but everything, like the ability to get a therapy dog to keep your kid from walking through traffic because he pushed out a screen on your ground floor window, or the ability to have health care that pays for in-home therapy services, or the ability to have health care -- it's frightening, isn't it? How lucky you have to be to live in this world?

Then again, everything is frightening if you think about it. If you think about it, you could be scared 100% of the time about everything from very obvious dangers like the pickup trucks that never seem like they're going to stop before they pull into the road to less obvious dangers like one day maybe they'll decide they don't like you at work and then you're out of a job and out of health insurance and have to think about how you're going to get money. It's possible to start thinking about things like that and picture yourself with two seventeen-year-old boys at St. Vincent's trying to buy a game of "Sorry!" and hope it has all the pieces in it and drive yourself insane with the fear of it all. It's possible to just start thinking one day things like: How'd it get this way? Maybe this really is not my beautiful house? And then you're sobbing to yourself behind the wheel of a giant brown Buick car with a sagging interior roof as you drive along I-94 away from your efficiency apartment in the bad part of town, but not the part that's really bad, just the part that's bad for people who are white kids from the suburbs.

"The real troubles in your life are apt to be things that never crossed your worried mind. The kind that blindsides you at 4 p.m. on some idle Tuesday . Do one thing every day that scares you."

One thing? Just one thing?

You don't actually have to try to do things that scare you. Fear comes at you, and generally from a place you never expected, like just across the stream.

We decided to visit waterfalls this summer. By "we" I mean of course just "me." I decided. We go on nature walks, the boys and I, to get out of the house and get some fresh air and exercise and give Joy a break from the boys for a while, and give the boys and I a break, too, so we can live by our own rules for a couple hours, while we walk through the woods. Having exhausted many of the local nature trails in our county, I thought I would branch out to nearby counties this summer.

There is a state park near us where there is a waterfall. It's a pretty nice waterfall, a forty- or fifty-foot rock wall with water falling over it in streams and sheets and little trickles. We'd been there once before, maybe a year or two before. Probably the year before, when the pandemic first hit.

So that was where we started this summer: we revisited that waterfall, walking down the narrow quarter-mile path to the grotto where the waterfall slips over the stones to pool below before running away in a small brook.

This time, though, we didn't have Joy with us, so the boys were free to extend their stay at the waterfall. We took some pictures and felt the water and looked at the waterfall, and then, having done everything you can do at a waterfall, or at least at that waterfall, we moved on down the trail. Last time through, we hadn't done this. We'd just gone back to the car and gone home. This time, we went the other direction, and walked out along the path that runs parallel to the stream.

It was actually a beautiful walk. It was late May, when you can feel the heat of the summer waiting just offstage, the sun bright and the trees green and the water sparkling. If it was marred, it was marred solely by the presence of other people. There were, of course, other families and groups walking along on the paths, something I can't stand. I like to have the nature trails to myself, or to ourselves when I'm with the boys. I don't want other people around looking at us or nodding politely to us as we pass or judging us for walking into the river to wade around a bit or showing up in my photos so that years later I can only remember the nature hikes with strangers wearing weird hats in them.

When Sartre said hell is other people, he didn't mean it literally. He meant that the existence of other people means we are constantly judging ourselves through the means other people have given us to judge. We know that we are objects to other people, other people who view us and judge us, and because we know they are doing that (because we are doing it to them) we judge ourselves through their lens, using the knowledge of ourselves that they have.

I don't want other people around making me judge myself. I don't want people wondering why I'm stopping to take a picture of a particular tree branch or rock. I don't want people considering why Dylan wears a safety harness that looks like a parachutist's vest without the parachute. I don't want people thinking about me, or the boys, period. Not good thoughts, not bad thoughts, not simply curious thoughts: I would prefer that nobody be around to notice us, ever.

I'm not sure what Dylan gets out of the nature walks. For that matter, I'm not sure what Jude gets out of them, either. Jude likes to go on them with me, or at least doesn't complain about them very much and occasionally finds things he likes about them. One time he found a rock he liked. It was to me just an ordinary rock, but he liked it, and he carried it on the walk. Then he put it in the glove compartment of my car, where it sat for nearly two years before one day, Dylan got mad and opened the glove compartment and threw the rock out my car window while we were getting ready to go grocery shopping. I left it there but I kind of regret that now.

Dylan on these walks is mostly impassive, sometimes a bit upset, but usually just walking along quietly and tapping his forks against his face and not appearing to notice or look at anything.

He's aware, though, that the walks at least have some definite beginning and end. If we go on a trail we've been on before, one he knows the route for, he will sometimes hurry us along. If Jude stops to throw rocks into the water, as he likes to do, or I stop to take a picture of a flower, as I like to do, Dylan will sometimes pull at my arm or continue walking, trying to get us to the end of the walk so he can go back to his real life, I imagine. So I've gathered that he's not overly fond of these walks, but that he doesn't oppose them strenuously enough to end up causing him to go into a fit of anger and start pounding his fists into his forehead hard enough to cause bruises and bumps, requiring us to strap on the wrestling helmet we bought him for those occasions.

That first waterfall trip went so well that I decided the theme of waterfall-based nature walks was a great one for the summer, and so I checked to see where there were additional waterfalls in Wisconsin. It turns out that there are not a lot of waterfalls in southern Wisconsin. There aren't a particularly great number of waterfalls in Wisconsin, but what few there are are generally several hours north of us, in the vast area of Wisconsin that I've only rarely been to.

But there was a man-made waterfall not that far from us, about an hour away, near a small lake. The website -- waterfalls have websites -- said that it was made for some purpose or other, I don't remember, but the pictures showed it to be pretty much what you'd expect a waterfall to look like. I mean, it wasn't just rainfall runoff slopping over a concrete barrier.

There was something about the idea of a manmade waterfall that made me think maybe it wasn't a real waterfall, at all, and I can't figure out why the fact that it had been created by people made it seem less of a spectacle to go visit, but in any event the fact that it was manmade was not enough to dissuade me from going.

We drove the hour to get there, following the GPS route carefully. One thing that I didn't know before using GPS to drive myself to a manmade waterfall a county away was that GPS maps do not actually know where a waterfall actually is. Following the GPS led us through several small towns along rural highways, then a turn into a hilly area with twisty and turny lanes that wound their way between the two types of houses you find near lakes. You know the two types. There are the big McMansiony houses that are about 14 days old and have all kinds of boats and ATVs and the like parked around the five-car garage. And then there are the houses that appear to have been airlifted to the region by tornado about a century ago, with a small fishing boat half-off the trailer on the gravel driveway hidden beneath giant willow trees in a yard that is more dirt than grass. Hell is other houses.

Then, at a random point on the winding road, the GPS announced that we were here. But here was just a spot on a road, clearly not any kind of waterfall, and not in the immediate vicinity of any waterfall that we could spot.

That resulted in us having to backtrack back into town and try again, driving around the two streets of the city until we saw a sign that pointed us to the park that was built around the waterfall that had been built by the lake, which I'm pretty sure was natural. The lake, not the park.

It was just a short walk to the waterfall from the parking lot, making it somewhat absurd that we had brought a backpack with a bag of cheese puffs, six Hershey bars in a lunchbox with an icepack, several little tubes of cracker sticks with cheese, a bag of goldfish crackers, a box of SpongeBob Gummi Krabby Patties, and two bananas, these being the foods I bring along whenever we're going to be out of the house for more than a couple hours. I had also brought a waterbottle for the group, and one of Dylan's water bottles. Dylan doesn't like to drink water out of anything but (a) a bubbler, or (b) a very specific kind of bottle made by one bottled water manufacturer. Dylan also doesn't like to drink water from a bottle unless he is in the house. So if you're doing something that makes you thirsty or hot or both, you sometimes have to force Dylan to drink water, the way we did the time we took a vacation to Florida and on the second day of driving, we stopped at a gas station in Georgia and bought some bottled water and then our oldest son Dustin, and Joy, held Dylan steady while I forced him to drink water by gently squirting it into his mouth, somethine we had to do because he had not, to our knowledge, drunk any water in the prior 24 hours.

Jude's a different matter. Jude typically won't eat outside the house. No matter how long we go or how hungry he is, he doesn't like to eat when he's not in the house. We are not sure what the reason is. It might be because Jude is very much into order and not disrupting it, and if he eats a food at home it seems strange and untenable to him to eat that same food anywhere but home. It might be because he doesn't want to have to poop in a bathroom that's not our own. It might be just because it is. If you ask Jude to explain it, you will get an explanation that sounds ad hoc and does not always make sense. If you ask Jude to explain a lot of his behaviors, you will often get that type of explanation. Sometimes he seems like he makes up rules to justify his actions, almost as though he knows they're somewhat unusual and he doesn't want to feel like he's unusual. You might, for example, ask him why he can eat Cap'n Crunch Crunchberries at home, but not at school, and he might say "If I eat them at school it might bother my friends," a statement that could be true, but also could possibly not be true. So maybe he's conscientious about his friends or maybe he just can't bring himself to eat the cereal at school for whatever reason and doesn't want to say that. Maybe he doesn't understand it himself and so he makes up a rule because who doesn't want their own actions to make sense?

So we had the snacks along anticipating a hike that was much longer than the actual brief walk downhill to the waterfall. The hill was somewhat steep, but had an asphalt path. Dylan took the hill extremely slowly because he doesn't like heights and he doesn't entirely trust asphalt. When he was 7, Dylan slipped on a wet patch of asphalt and has never forgotten it, and has been since then extremely cautious about walking on asphalt. He walked in tiny steps down the hill until I had the idea of telling him to walk on the grass, after which he picked up the pace a little, but not a lot, because Dylan is not really into nature walks at all, even if they're very short and end in a waterfall.

The waterfall itself was pretty good. You couldn't tell it was manmade. It didn't look like someone had run a river over a Walmart or anything. It looked like how you want a waterfall to look, and it led into several little pools before stretching back into a "river" that was about 10 feet wide and very shallow. These were the only kind of rivers I ever saw growing up: narrow, shallow rivers running through parks. So I was understandably confused when teachers would talk about using rivers for shipping things or how the explorers and pioneers would take canoes up the river, since it seemed impossible to me that anyone could do that.

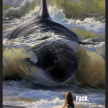

You're not supposed to wade in the river there, but there was nobody around and I couldn't see why we couldn't wade in a bit, so Jude and I took off our shoes and socks. Dylan didn't want to. He had settled himself by a tree and didn't want to get up. So Jude and I slid down the steep bank, about five feet tall and barely climbable, and started wading in a bit. We took a few pictures and then were going to get out and maybe hike up the river a bit and see if there was anything interesting when I saw the dog.

The dog was across the river, up on the other bank, which was about ten feet tall. A moment after the dog appeared, a man came walking up. The dog was not on a leash and was looking at us. I told Jude to climb up on the bank by Dylan and start putting his shoes on. Jude hadn't yet seen the dog, and Dylan had not either.

As Jude started to get up the bank, the dog came bounding down the other side and started wading across the river towards us. I put myself between it and Jude and told Jude to get up by the tree by Dylan. The dog stopped a few feet short of me, bouncing around nervously or excitedly, and looked left and right. It started towards the bank towards my right, and I stepped there to block it. That was when Dylan saw the dog.

Dylan screamed at the top of his lungs, an incoherent shriek that seemed to go on for about thirty years. During that time, Jude looked to see what was going on, and the dog charged past me and up the bank towards Dylan. By then Jude was up on the grass, too, and was between the dog and Dylan.

The dog started barking and I scrambled up the embankment as Dylan tried running away and ran into Jude, who also was trying to run away. The dog veered away from them as I got to them, but was still barking angrily and loudly and circled back.

Jude tried to run away while Dylan tried to get behind me, and I had to reach out and grab for Jude, getting him by the collar. That exposed Dylan and the dog came charging at him. Dylan had not stopped screaming and now Jude was, too.

The dog owner at this time was on the opposite shore calling the dog by name.

I alternated between telling the boys to calm down and stand still by me, and yelling at the man to come get his dog. The dog was circling us and occasionally feinting inwards towards us. By that time I had both arms around Dylan to keep him from trying to run, holding him sideways so I could keep my legs able to kick the dog, and Jude was grabbing onto my back, both of them sliding so they were kind of behind me and kind of on my side.

I continued to tell them to try to quiet down. They were both screaming and crying now. The man had crossed the river and kept just calling his dog. That was all the effort he put into it: calling its name, not even very loudly. The dog circled us, occasionally feinting in, barking the entire time. You could see every tooth in its mouth. It looked kind of like a golden retriever dog, but was pretty big, and it sounded mean, not like it was playing. Whenever it came near us, Dylan would try to climb up me, while Jude would try to scramble around me to avoid it. I was telling them it was okay and I would protect them, while trying to keep my legs clear and my body between them and the dog. When the dog would come close I would kick at it to keep it away.

The man got up onto our bank and now yelled at the dog, which then took off running towards the other side of the lake from the parking lot. The man yelled the dog's name and then took off running after it, and hollered over his shoulder that "she's not usually like this," which: F--- you that wasn't the first time that dog has done that. In mere moments they were gone, the only sound being the boys crying and a distant bark followed by the man yelling the dog's name.

Both boys collapsed on the ground. Dylan was making the same sound he makes when we go to the doctor, a sort of low level whine/groan, over and over. Jude was trying to stop crying and kept telling me that he wasn't scared of the dog.

I told him I knew he wasn't scared of the dog and that he was brave. He asked if the dog wanted to hurt them.

What are you supposed to tell him? This is one of those moments where an entire worldview can be shaped. Jude deals in concrete facts and things do not change in his world. Joy read an article a while ago that said Lucky Charms might have an ingredient that causes cancer, and she told Jude. He not only will not eat Lucky Charms anymore, but when he sees them he announces loudly that they cause cancer and will kill you, which makes him very fun to go grocery shopping with, especially if there happens to be someone in the aisle actually buying Lucky Charms.

So what to say? Yes, I think the dog was trying to hurt him, and yes, he should know that in this world dogs may try to hurt him, that not all dogs are nice, that not all people are nice, that the world is a scary place that is full of danger and terrible people, that you have to be on your guard at all times, that it may be actually getting worse, that every time you go out your door you will walk by 1, 5, 20, 50 people who would just as soon kill you as look at you, who will be careless and rude and negligent and mean and who will want to hurt you just because they are not happy.

Quid est veritas?

"The dog just wanted to play with you and was happy and excited," I told Jude. I hugged him, and hugged Dylan, and we walked back to the car, tears drying on their cheeks, the adrenaline draining from out of us, leaving me hollow and tired and sad. As we walked I kept them in front of me, because the dog had run off behind us, and so for now the danger seemed ready to come at them from behind, although I know the danger is in fact everywhere all around us and is always aiming at them. The world is a cold cruel dangerous well of darkness and it takes every opportunity to prove that to us, to remind us that we will die sooner rather than later and that we will mostly be miserable during the too-brief time we have fended off death.

That's the world I live in. That's the world I was raised in, my mom carrying steak knives in her car and putting one under her pillow to fend off rapists, locking doors in bad neighborhoods, putting wallets in front pockets when you go out in public. That's the world around us: people shooting and strangling each other and getting away with it because juries don't care because nobody cares because the world is on fire and soon we will all be ashes. That's the world I wake up to every day and slog around in and hope for just a few moments of beauty, of happiness, of peace. Hope for a quiet moment splashing in a stream with my son, who doesn't understand much of anything about how things actually work.

That's not the world Jude and Dylan will live in, not for as long as I am alive. I will stand in front of them, shielding them from that world, for as long as I can. I will put my arms around them and pull them to me, I will let them climb up away from the danger on me, hide behind me. I will kick my legs out at the world that wants to hurt them. I will let it hurt me. I will let it sink its teeth into me and tear my flesh away bite by bite, but it will not hurt my boys while I still have even one breath in me.

About the Creator

Briane Pagel

Author of "Codes" and the upcoming "Translated from the original Shark: A Year Of Stories", both from Golden Fleece Press.

"Life With Unicorns" is about my two youngest children, who have autism.

Find my serial story "Super/Heroic" on Vella.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.