The Twits: A reflection on children's literature

Why, for an abused child, The Twits is solace

“What a lot of hairy-faced men there are around nowadays.

When a man grows hair all over his face it is impossible to tell what he really looks like.

Perhaps that’s why he does it. He’d rather you didn’t know.”

So opens The Twits, one of Roald Dahl’s flagship children’s novels and, on a personal note, a piece of fiction that has rented blocks of my mind for nearly twenty-five years.

This is no small feat. While it is arrogant to stay on myself for the moment, I need to acknowledge the shear volume of literature I was exposed to as a child: everything from the German stories of Grimm, the painfully English Mr. Pinkwhistle (a name that has not aged well), all the way to Charlotte’s Web and that story about Wild Things. Yet despite having hundreds of novels shoved into my little impressionable brain, none have managed to take root. Who was Mr. Pinkwhistle? What was so special about Charlotte’s Web? Which stories belong to Grimm again? Honestly, I haven’t a clue. For The Twits, I could write you a five page synopsis.

But I won’t. That would be very boring.

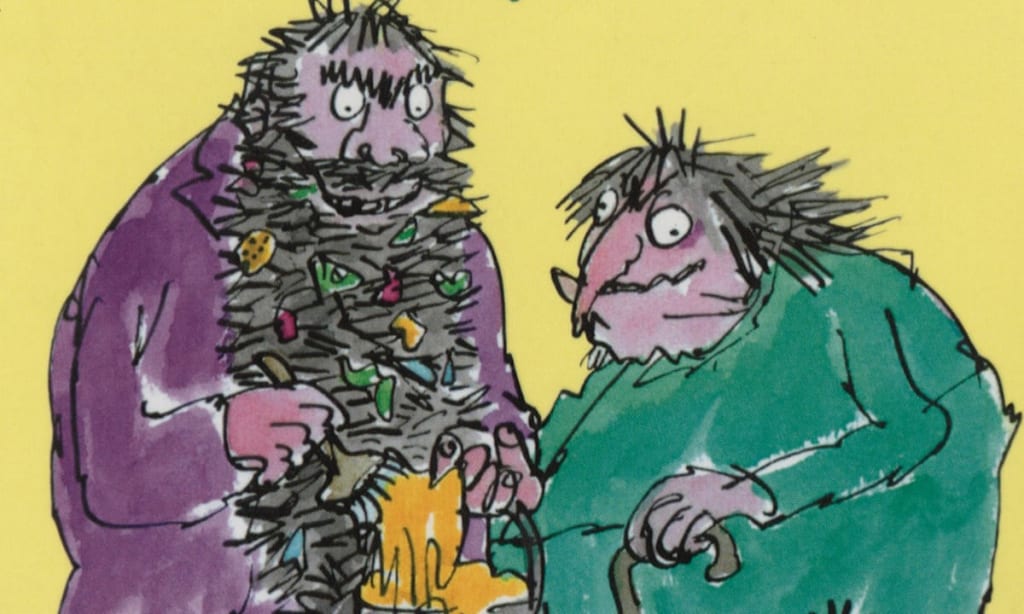

Instead, let me give you it in brief, in case you’re not familiar. Dahl, an English author of Norwegian decent, had a reputation for work that rather bordered on the dark side (never getting quite as far as covering child murder, but likely only because his publisher said he wasn’t allowed), and The Twits is a perfect example of this. Set in a house with no windows, the titular characters, an ugly, vile, baleful old couple named Mr. and Mrs. Twit, spend there days performing horrid tricks on each other that range from moderate gaslighting to open torture. They also catch and eat birds by putting glue on their garden tree, causing the animals to have to rip their only legs off if they want to escape.

Not quite a classic set up for a children’s story. However, although it isn’t a premise that you’d be surprised if attributed to Stephen King, the novel proves hilarious, full of moral lessons, and deeply unique.

The opening three lines, written at the top of this article, demonstrate Dahl’s skill with words. He creates the image in the readers mind that not only are there loads of people with beards around, but this is in fact different to what it used to be (a child, with no way of knowing, will automatically take both these facts as gospel). After establishing this new reality in his reader’s head, he immediately makes it sinister, “When a man grows hair all over his face it is impossible to tell what he really looks like. Perhaps that’s why he does it. He’d rather you didn’t know.”

Within three lines, the child’s mind is paranoid and curious. ‘Perhaps’ is used to let the reader create the thought themselves, but the thought is clear: these beardy men are not to be trusted.

I, like millions of others, was gripped. By the time the characters are introduced we are already convinced of their villainy, making it a joy to watch as they abuse and debase each other time and time again, with the animals they love abusing so harshly getting their own vengeance towards the novels end. Fundamentally, it is a story about how bad things happen to bad people, and as a child this is a message gratefully received.

For me, it was particularly salient. My mother was wonderful, and it was her who read me these stories. My dad, on the other hand, was not.

As we’re discussing children’s literature, I won’t get into the dirty details of it. Hidden bruises, broken teeth, and fractured self-esteem were minor points on the road of his abuse. It left me with a desire for escape, sure, but it also left me with two feelings I believe must be held by any abused child: terror and powerlessness. Not a hot take, I know. Yet these feelings, in a more mature mind, bring forward a great sense of injustice, and it is all this that The Twits tackles.

You see, villains aren’t uncommon in children’s books: sly foxes, grumpy farmers, dragons, elves, and nosey neighbors. Real evil, however, is largely absent.

Dahl was a man familiar with evil. Having fought in World War 2 and been raised in private schools where whippings and beatings were par for the course, he had a lot of personal experience of horror, perhaps culminating in the death of his seven-year-old daughter when he was 43. As such, the monsters in his stories hit the mark,

Mr. and Mrs. Twit are evil, which you’d think an abused child wouldn’t want to read. But in real life these children see evil flourish, they see it unbeatable, and they see it succeed. In The Twits, they see it slowly eating itself alive, they see it as miserable and, by the end, they see it beaten. This provides a catharsis inexplainable if you haven’t been in the position of an abused child, a feeling that perhaps things are terrible right now, but this is what happens to bad people, just you wait my son.

Stories are great for the imagination. They’re great to teach empathy, respect, tolerance. Sometimes, however, they can be so much more than that, and this book is a solace that helps children through the dark and into the light, and what better message is there to give a child at bedtime? Because when the world is awful and terror and helplessness are ways of life, what is there other than the final words of a novel to give a child peace?

“One week later… there was nothing left in this world of Mr and Mrs Twit.

And everyone, including Fred, shouted…, “HOORAY!” “

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.