Hettienne and Haagen Changel

The fog of mourning spreads through their home—wrapping each of them in their own way. Father has left the door wide open ever since mother died. There is finality in the way father wanders out, leaving Hettienne and Haagen alone. It is Christmas day.

Furnace heat from the floor vents interweaves with wood smells from the stove. A candle that should have been blown out flickers in its glass jar. The flame illuminates the candle’s blackened label that mentions spruce. Haagen, alone, manipulates the arms of an action figure holding a rifle so it is bowing a cello. The figure sits on its wooden building block, the red-letter C, performing a ballad for Haagen.

The holiday books spend most of every year living in a blueish cardboard box from father’s office. It had originally held reams of printer paper and there was no harm in him taking it home once it was empty. He explained this truth to Haagen when he asked. Hettienne never asked where the boxes came from or if it was okay. Now she shines a flashlight out her bedroom window, relishing how far the beam travels and the shadow shapes cast across the snow when she lights up the big tree in the yard.

The ornaments and lights come up from the basement in their own printer paper boxes. There is one for red glass balls and another for red plastic apples. Always packed with care was the purple glass spire that went at the top of the tree where other families put stars and angels. Another box is marked Haagen with two heavy black underlines. This box contains his collection of nine ornaments celebrating each of Haagen’s nine years. An autobiography in ornaments, Haagen’s box contains an ice skate to commemorate one year when he tried ice skating on a big family vacation to New York. He has an ornament for that difficult year when he had to play pee wee soccer so he could learn about being on a team and how to get along with other kids.

Haagen had picked a lot of dandelions that year.

His dandelion ornament usually hung on the tree beside his sister’s sunflower. It commemorated her first and only summer at sleepaway camp. That August, when mother and father came to pick her up, she was seated contentedly on her cabin’s front porch while the other kids were assembled in the Great Lodge.

Mother’s passing was as sudden as the release of autumn leaves from autumns trees.

One day, while Hettienne was in charge, mother died beside their sleeping father. And then father went away that day too. Hettienne, calling her brother up to her room, attempted to make him understand that they were orphans now. Haagen told his sister that their father had not left them for good, but only to be with mother as she was going away. Hettienne hugged her brother close and forgave him his youthful naivete.

Almost three years older than her brother, Hettienne feels doomed to understand too many things. In keeping with the spirit of Christmas, she allows her brother to believe whatever he needs to believe.

“Father is going away because, without mother, he can’t be around us,” Hettienne says into her brother’s pale winter eyes.

Holding him away from her, she temporarily denies him the comfort of her lap.

Without tears or a swollen throat, Haagen responds, “He is away now. He doesn’t want to bring his woes home to us. But he will come home. We will mourn mother. We will still be a family.”

“We are a family. But not like we were, not still,” and Hettienne releasing her brother’s shoulders, now cradles her brother’s head in her lap, both of them staring through her open bedroom door, into their darkened home.

Their father comes home, just as Haagen believed he would; however, they are not a family like before. Hettienne is right about that.

After their mother’s death, the children gave father space to bring her clothes downstairs, a few at a time. He brought her shoes down too, zipped up in a worn rolling suitcase. Items from drawers went into garbage bags. Clothing items from the closet were left on their hangers and laid across the chair near the front door. Sometimes, if the hanger-clothes were in a plastic cover like the ones from the cleaners, they would slide through the others, right down onto the floor. Hettienne passed a mid-length orange dress, it wore its slippery plastic while making its escape from wherever the other mother-clothes were off to. Hettienne brought the dress upstairs and hung it in her closet in her room until the day came when it would fit her.

When mother’s clothes were all gone, father went about removing her wooden mirror on its tilting stand, her bureau, her vanity with its lights, and the bed they shared since buying the big home with the big maple outside. When father started sleeping on the couch in front of the fire in the living room, he stopped thinking about mother and most other things.

There is a narrow table in mother’s study where she displays some family pictures in frames. There is a circle of lace beneath each photograph. The table is draped with a floor length yellow cloth.

Sitting beneath this table now, Haagen holds his most trusted stuffed animal to his chest. The faded dog, battered by his travels, desperately seeks to comfort the boy on this Christmas morning. Haagen’s head and heart are wired for getting up before dawn, especially on Christmas Day. That’s why mother and father started hanging the stockings on the children’s bedroom doors. When he presses his stocking to his face, he smells his mother’s lotion, Lilly of the valley, and peppermint from years of receiving candy canes buffered by the season’s obligatory toothbrush and toothpaste. If the light at his mother’s desk were on, Haagen would be warmed by the yellow walls of this safe space. He sits in darkness now.

With mother gone, and father gone in a different way, Hettienne passes by her empty stocking, hanging limply on her door, and makes her way to the top of the stairs. She briefly reaches out for the purple spire on top of the tree that nobody can reach unless they stand on the top step, then she thinks better of it and makes her way downstairs. Most of the ornaments remain in their boxes. A strand of lights wraps the lower third of the big fir tree. A helpful uncle, determined to give the kids a normal holiday, had flown in from California, but had been suddenly called back. Hettienne plugs the strand into the last spot in the power strip and lets the green-white Christmas light shine.

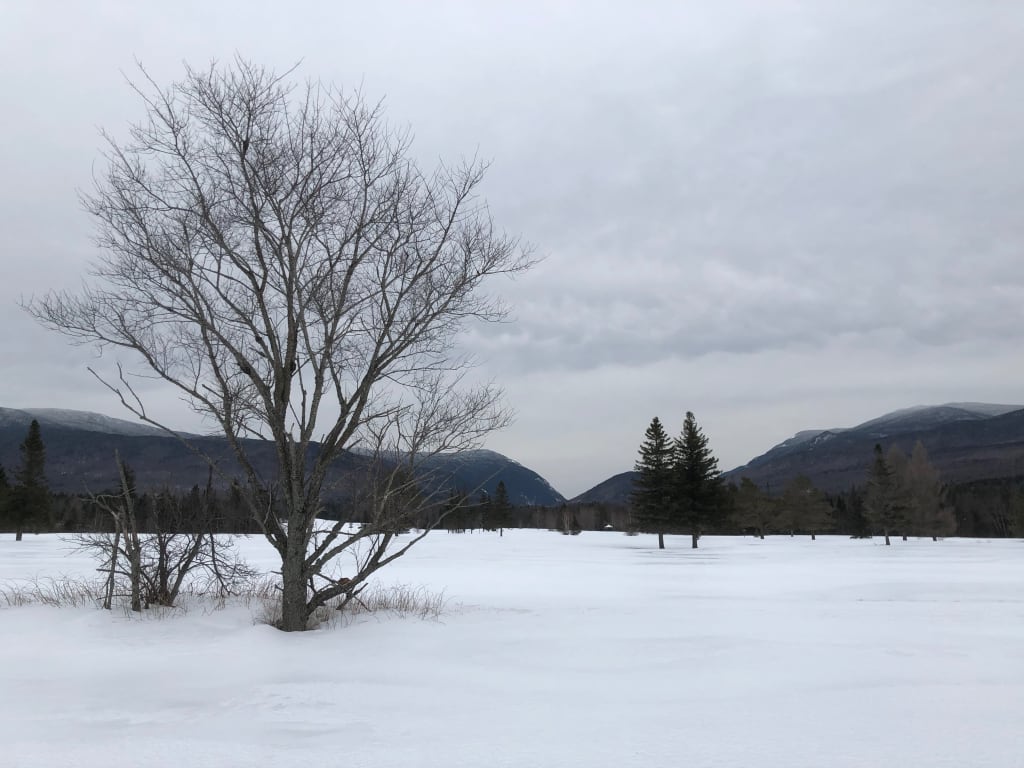

Outside their home snow falls as if in a postcard. New England Christmas Days can be as often bleak as they can be majestic. Mother and father told the children about a Christmas after Hettienne was first born when it had rained, and the wind blew hard enough that the entire state lost power. Father had built up the fires in the woodstove and the fireplace. Mother went up to her study, beneath the yellow draped table, and brought down the gift bags they were supposed to bring to the New York family the following day. Together, mother and father ate all the candy out of their niece’s and nephew’s stockings, and they drank all the aunt’s and uncle’s wine.

Haagen adopted the spot beneath the yellow cloth when he was very young, too young in fact to be sitting alone, beneath a table while mother sipped tea and recorded thoughts in her journal. Haagen recalls that the presents had to be moved from his spot and closed up in the small closet, where they would be more secure from his curious little hands. Haagen opens the closet now. There are no presents inside. Just coats and that distinct smell of coats in closets.

Making his way down the back stairway, into the kitchen, Haagen puts on the long leather mitten that mother and father wore when they worked the woodstove. He clenches his stuffed friend under his arm and cranks the hot brass handle that unlocks the front. Feeling the heat chap his delicate lips, Haagen closes his eyes a moment, and imagines the flames wrapping his face and reaching his ears. He places a log into those flames, and another one, then closes the stove. Replacing the mitten on the pile of split logs that father brought in from the stack on the back porch, Haagen catches site of movement out of the corner of his eye. It is coming from outside, perhaps in the yard.

It comes as no surprise that the movement, followed by the sounds of hurried joy, is just the arrival of Christmas family at the neighbor’s house. Haagen, unsmiling, watches a dog escape the car, unleashed, and pursued. He waves to the dog, but dogs don’t always wave back. Decoratively wrapped boxes in big bags are delicately removed from the line of cars. Kids who stretch when they stand in the predawn darkness, still in their pajamas, turn back to find their coats and hats, then hustle their slipper-feet into the warmth of the house next door.

Haagen scoops up an armful of logs to replenish the small stack beside their woodstove. He drops the logs, turns to close the back door, and decides he would like some tea. Tea is the only thing he knows how to make, and he thinks his sister would like some too.

If the tree weren’t situated beside the stairs, Hettienne would never have stood a chance of getting the lights around it. They aren’t perfect, but now they are hung on the tree, not coiled in a printer paper box, and that is enough. The apples and red balls went up easily. She dragged over a stool mother used for reaching the big mason jars of dried beans from the top of the kitchen cabinets. She evenly spaced the red ornaments, generic ones, her father used to call them, gifts from somebody or other, he used to remark. Then she went to work on her box of twelve special ornaments.

Her first ornament is a duck peering through the zeroes in the number 2009. She has never looked at this ornament very closely, it was always just hastily hung with the others. In past years, once the tree was decorated, she and her brother were allowed to open one special gift each, in front of the fire, and drink sparkling cider while mother and father drank champagne and listened to old records. The duck is holding binoculars that only look like the number 2009 when he is facing you. When you look at his profile, he is wearing a tan vest and a brimmed hat. Hettienne imagines him as a bird watcher and that confuses her. Ducks are birds. She never watches for birds herself and doesn’t own binoculars. This ornament isn’t special to her. Then—she does look out her window quite often, always into the night—but night is when birds are sleeping. What do you call owl watchers? She hangs the ornament on the tree.

When the kettle boils, Haagen knows the first thing to do is to turn off the flame, then move the kettle. Mother has shown him many times and he doesn’t even have to think to get it right. Tea is best made with boiling water, so it is important to have your tea bags, two of them, in the pot, standing by. Haagen can’t find the special Christmas mugs that he and his sister get to use during the holidays. His is shaped like a snowman and its head is the lid. Hettienne’s is a log cabin. Its whole roof comes off. Father once joked that she was drinking up a whole family and all their cares and woe. Haagen asked, what was woe? Mother said it was sadness. Haagen thought she meant loneliness.

The 2010 ornament isn’t quite as odd as the binoculars duck. It is a ballerina in mid twirl. A ballerina’s twirl is called a pirouette. Hettienne knows that it is the next ornament in the sequence by the little 2010 written in black marker on the bottom of the dancer’s foot. She hangs it on the tree. Next 2011—she was only three, how much could she have done by three? She is reminded when she finds the little wooden calculator ornament that has a smiling face above the buttons where the screen ought to be. Hettienne started pre-school when she was three. She didn’t like to run or play, but she enjoyed quiet lunch times and her calculator.

It is impossible for Haagen to reach up for the tea tray with his friend tucked under his arm. Worse, when he tucks him under his chin to free his arms, Haagen finds he can’t look up to see the tray he is reaching for. Placing his friend beside the two bowls of cereal with a command not to eat any while he is away, Haagen reaches for the tray, carefully slides it off the counter, and turns around to open the kitchen door with his back.

Light wraps him up and shines through the kitchen and all the way out into the backyard. As he turns to navigate the room, he feels a holiday glow like he never expected this winter. Hettienne’s proud smile stops him in his tracks. The Christmas tree is glowing hope. Hettienne is glowing too. She is the comfort of a mother’s hug imbuing the big living room with all her warmth. Haagen moves across the room reverently. He places the tray on the coffee table, hugs his sister, then sprints back into the kitchen to retrieve his friend who should get to enjoy this moment too.

Haagen returns, wiping tears from his reddened eyes.

“I just wanted him to be with us to see what you did,” Haagen holds his dog up for Hettienne to kiss him on the nose. She does.

“I got everything up except some of my special ornaments. Yours are here too if you would like to put them up with me.”

“You made it Christmas in here. -I made tea. I poured us cereal too, but there isn’t any milk.”

“We can eat it dry. Tea makes it Christmas too.”

“I’ll bring in some wood. We can build a fire and have tea and cereal while we wait for father.”

“Okay, you get the wood and the cereal, I’ll crumple the newspaper.”

“Then we can wait for father.”

“Then we can wait for father.”

Marlon Changel

Still snowing. Better to have parked beneath the roof. Scraper should be in the trunk. Marlon considered these things while he swiped his identification through the scanner at the front door of his office building.

J’aime mes enfants, quoi qu’il arrive dans cette vie.

I love my children no matter what happens in this life.

Marlon had never learned the man’s name, the man who ran the circular buffer along the tiled floor of the main lobby. He was a Jim or a John probably. The security desk was unmanned. Must be close to dawn.

The light above the elevators was out. That’s something I should report. But John or Jim may have done it already.

Marlon stood looking at the man in the loose-fitting gray coveralls. Then, regretfully, Marlon held the janitor’s stare too long. The man removed his headphones and offered a half wave. The elevator beeped and the doors opened. With a half nod, Marlon dashed out of site. Without thinking, he made his way to the back corner of the empty elevator car after slapping the button for the top floor.

He wasn’t used to unlocking the outer door to his office. He couldn’t remember the last time he had arrived at work without a warm greeting from his assistant, his coffee poured, waiting for him beside his folded newspaper. He never even had to hang up his own coat, a fact that hit him as he searched for the coat rack. It was behind the tall bamboo in the ceramic pot.

His inner office door was closed but unlocked. He flicked the lights on and then thought better of it. He wasn’t here to work. He was just here. Marlon moved to his desk in the dark and pulled the chain on the desk lamp. The room remained dim, now glowing green.

Marlon scanned the walls displaying his fine taste and awards. He closed and locked the door. Moving to the brown leather chesterfield, Marlon Changel dropped, gripping his face he slid down the smooth back of the couch, then melted off the cushion to the floor. The tears came and air couldn’t get to his lungs. He heaved through the tightness that only complete sorrow can bring.

A French horn kicked off a symphonic arrangement in Marlon’s mind. A trombone slid its notes alongside it and a timpani roll rumbled a warning of more to come. A fanfare of trumpets startled Marlon’s hands from his swollen face. Before he could feel fear, Marlon was strengthened by the long harmonious bowing of the violin section. Violas and cellos reinforced the sound until it was strong enough to lift him back onto the couch. A playful bassoon, supported by a tenacious oboe, focused Marlon’s memories on the first time he and Monique had seen the big maple tree.

The house wasn’t for sale and so there was no showing. Monique spotted the tree during an aimless drive. Marlon pulled in front of the house. A piccolo sounded the spontaneity of Marlon’s offer that day, an offer made confidently and only possible while in the company of what the story books called true love. The cymbals crashed this feeling through Marlon’s mind once again. While the standup basses plucked a droll staccato march, the bells took frontstage in the center of Marlon’s chest. Cloth wrapped mallets rung each bell singing out over the bass line. The flutes and clarinets warmed everything up for Marlon and the alto saxophones plugged the gaps where cold and darkness could get in. When the baritone horns and the tuba joined the muted plucking of bass strings, in support of those bells ringing unmuted euphoria across each other’s tones, Marlon felt himself standing.

It had been ten days since Monique had passed. She would have loved today. The snow began falling on her final day, and kept falling, making this the whitest Christmas in history.

She loved Christmas and its magic. My family.

Joyeux Noel, ma belle famille!

Not bothering to turn off the lights or shut the office doors, Marlon snatched his coat from the rack behind the bamboo and sprinted for the elevator. Uncharacteristically, Marlon pounded the Lobby button five times, in rapid succession, with a closed fist. He put his coat on and rummaged through its pockets. He found what he was looking for and temporarily got himself under control just in time for the doors to open out into the lobby.

Happy Holidays John! Get out of here as soon as you can, huh? It’s Christmas!

Marlon shoved three crumpled one-hundred-dollar bills into the man’s hands, clutching him in a desperate double handshake.

Merry Christmas Mr. Changel! The name’s Jim! Drive safe! -Lot of snow out there!

Realizing for the second time that he really should have parked beneath the roof, Marlon tore through his trunk in search of the scraper. The valets had always taken care of this for him on especially snowy days. One of their names was Tanner. He didn’t know any of the others.

Failing to find his scraper—that’s right, it was in Monique’s car. Marlon went through his center console and found a CD case, Nora Jones. He scraped at the ice that formed over his still warm car and thought it best to warm the engine. He mindlessly pressed the power button on the stereo and uncharacteristically selected CD instead of his usual Public Radio preset. Snow fell through the beams of his headlights and Nora Jones sang to him about the lines on his face not bothering her. She sang about how she has to see him again. She joined the symphony powering is mind. Marlon held it together, but just barely.

Letting the music play, allowing it to bring him back to his wife’s face and the way it looked by fire light, Marlon drove the Christmas-empty roads to his family. He thought about past Christmases.

Haagen had only just begun to understand Santa Claus. Marlon hung Haagen’s special ornament for that year on the tree, a Santa Claus in a lei and sunglasses they purchased on a small family vacation to Hawaii. Hettienne and Haagen’s necks craned as they stared up ten feet to the top of the tree, its purple spire twinkling. Monique shook Marlon from his own moment lost in the Christmas magic by clicking her wedding band against her empty champagne glass.

J’dore le facon dont tu te perds dans la magie.

And she called him to her with a smile and a beckoning finger.

Marlon drove faster than was safe in the current weather. He held closely to the memory of that past Christmas and realized that it was making him smile through his hurt.

He slowed as he entered the neighborhoods just off his highway exit. Nora Jones still sang, but he lowered the volume as if the music could disturb the families in their homes—all of them resting comfortably before waking to the excitement of the Christmas dawn that reflected off drifted snow, and would shine through their windows.

One home, at the corner near the last stop sign between him and his children, had a first-floor light on and a car running in the driveway. In the window sat a young man, the screen of a handheld video game illuminating his face in a sickly way. Marlon looked at the man, a boy really, too old for Santa, perhaps, but too young to be awake so early on Christmas Day.

The man with the video game, it turned out, was not looking at Marlon and judging him for being away from his family, drawn to work for no reason at all late in the night. He was looking at the car running in his driveway. Now Marlon was looking too. A two-door sedan with rust around the rear windows puffed gray smoke as it idled. The dome light was on. A young woman, maybe a handful of years older than the boy in the window, sat smoking and crying in the front seat.

Marlon knew these tears. She wasn’t sad. She had lost, lost something amazing, and lost it forever. She heaved as Marlon had heaved against his leather couch. She puffed smoke and breathed like it pained her to do so. Now Marlon connected with the boy in the window. It was because he was out of his car, out in the snow, approaching the boy’s home. Nora Jones sang through his open driver’s side, his car still running at the corner.

Marlon knocked on the sedan’s door. The woman started. The boy was gone from the window. Blank faced, but somehow still sincere, Marlon offered his hand. His coat was open and billowing black in the snowy wind, flapping around him. Her small hand in his, Marlon lifted her out of the vehicle. He briefly noticed that she was barely dressed before pulling her into his arms. She was rigid at first, but then accepted and quickly reciprocated an embrace exuding sincerity from a stranger. Now she could hear Marlon’s symphony too.

The young man of the house came sliding to a stop. Marlon, tears in his eyes, holding the boy’s sister in his arms, offered an open hand. With brief hesitation he took it, then his sister wrapped him in the hug too. Marlon slid out from between them, leaving the French horn to connect them with its broad, open-armed notes. Marlon moved to turn off the little car and roll up its window. He did this quietly and began to walk away when the girl turned. She smiled and held her brother close. Her mouth opened. Marlon nodded at her, mouthed Merry Christmas, and turned back to his car.

He heard Monique speak in that whispery way she spoke only to him.

J’adore la maniere dont tu te fais emporter par la magie.

I love how you get lost in the magic.

Monique Changel

Hettienne was right on time and was born in caul. Haagen was a little early and was born completely at peace. He didn’t cry when the doctor’s confirmed he was breathing. He stared at them, looked over at his mother, then back at their doctor, and it looked like he wanted to say something but lacked the words to make the room understand his thoughts.

Ma famille, c’est ma vie.

My family is my life.

Monique moved to the memory of her parents but became distracted by the memory of her husband. Marlon wore some kind of long tan leather coat with pronounced breast pockets. It covered his ass and moved fluidly around him when it was unbuttoned. He stood beside a fountain in Nuremberg, looking up at a cathedral. She watched from an outdoor table at a nearby café sipping a dark red wine in a small stemmed glass, gazing at her fiancée. It may have been pigeons that flew over her, or the flapping sensation could have been an effect of moving through memories so quickly.

Marlon wore a camera around his neck on a colorful strap, colorful threads woven through a wide strip of leather. He had a local paper stuffed in the front pocket of his jacket. He did that to fit in with the Germans. He said as much on more than one occasion. He popped the collar and buttoned both buttons on his coat before sliding his arm awkwardly into Monique’s. He looked like an artist, like a painter, like a lover completely at home in the city and still trying to navigate the pathway to her heart.

She had dropped her key one day in Montreal. He quickly reached to pick it up, read Mont-Royal on the plastic tag.

“I took you for a local,” he said in his accented Quebecois.

“My place is being renovated.”

“You sound quite local.”

“You sir, do not.”

“I’ve traveled.”

“That must be nice, where do you find the time?”

“I find it everywhere I go. La temps est partout.”

“Time is everywhere.”

Monique is in her study in their big New England home and she is ferociously journaling at her small desk beside the coat closet. Haagen is wrapped in a soft yellow glow. His soft, stuffed friend is seated beside him. He holds an action figure, an army man who holds a knife, Haagen positions it to be a flute and stands the figure beside the table leg to play him a lullaby.

She used to write about her day. It was a way to process the goings on. She sometimes copied sections from her journal into letters she wrote to her friends. There was something entirely old world about this practice, anachronistic, something more than it actually was. When she received her diagnosis, everything stopped. Now she wrote her thoughts, regrets, instructions, lists, messages for her children to read when she was gone, and stories about her and Marlon meeting in Quebec, traveling to Nuremberg, and honeymooning in Venice. She feared her destruction could shatter him and only in these pages would he be preserved.

Hettienne sometimes came into the room during these writing sprints. She moved like dusty rays of light across the carpet. She sat beside the yellow cloth-covered table. Hettienne brushed the cloth gently with her fingertips, enough to acknowledge Haagen, not enough to startle him or disturb their mother. She sat, eyes closed, listening to her mother’s pen move across the pages of her final soft leather notebook.

Monique reflected on the fact that she’d grown up, become educated, and had been courted by a man. Some of the stories, the one’s from before her children were born, shown brightly, others were dim things in the distance of her memory. As she reclined, now in the clawfoot tub Marlon had installed in their master bathroom, Monique recalled details from Hettienne and Haagen’s life down to their most infinitesimal detail.

She removed fuzz from Hettienne’s collar on the day of her first holy communion. Marlon had been opposed to the church, but these things mattered to Monique’s mother and so they were done out of respect while she was still alive. Hettienne had no opinion on the matter. The collar had been blue, the fuzz was yellow—an uncommon color for fuzz to be. Monique took another hit from the joint Marlon had rolled for her. It was pinched in an alligator clip that was glued to a plastic chopstick. Marlon was the most thoughtful of smokers when they were young, she recalled warmly. A leopard and his spots, she thought presently.

With her joint dry and the tub warm and the lights dim, Monique could easily travel around her current thoughts and her distant memories. So, she continued. Marlon in that ridiculous wool cap that he somehow made work with his damned corduroy blazer under a leather coat carrying around the local papers of the world. The way he spilled champagne whenever they toasted the occasion. The times he ran his fingers through her hair with his gloves on and how she could only stand the sensation because it was him.

Haagen, the first time he experienced death, a robin crashed into the window above the kitchen sink. The way he had silently pulled at his mother’s bathrobe, dragging her outside to the small feathery body. He struggled to dig the hole in the yard, refusing help and shovel with equal determination. His cuticles torn and bleeding, he managed to tear the web of lawn roots away, exposing the dark soil beneath. Haagen dug a shallow grave for the bird, first holding its broken form up to his ear for a long while, confirming it was truly dead. A plastic ninja rolled on a snare drum, a paratrooper figure strummed minor chords, and a wolfman slid a twig that was his bow across a stick that was his viola, completing a trio that celebrated the little bird.

Hettienne asked about boys once. Monique was tucking her in, and she sat back up against her pillow and asked why boys laughed at her. Monique decided to listen and allow her to expand her point. Hettienne asked why grown-ups were afraid of her. Monique asked why her daughter believed people felt these ways about her. Hettienne responded in bored French before rolling over, “Tout le monde penser si fort tout le temps.”

Everybody thinks so loudly all the time.

The day Monique died, a Tuesday, it was snowing outside. Marlon was asleep, his neck folded, resting his cheek on his own shoulder, his whiskers showing four days of growth, oily skin, baggy eyes, and a pile of tissues on the bedside table between them. She considered saying goodbye, but there were so many tubes in her and Marlon was finally asleep. Monique moved into her mind, past all current thinking, way back behind the memories, and from there she cast off. The dock of reality, one she recalled from the Danube just outside Germany’s Black Forest, became smaller in the distance. It became obscured by a low fog, then went out of site completely.

Monique drifted beneath the yellow table covering where Haagen enjoyed a slow song in his mind and the unwavering understanding from his fuzzy friend. She went to the maple outside of Hettienne’s room and looked up at her bedroom window where a flashlight searched the backyard in pursuit of night shadows. Marlon was wandering his office. What was he missing? Oh. He was being alone to spare the children.

Monique moved like this; the way people do when they no longer have the burden of body to hold them back. She watched Hettienne consider the Christmas tree in the living room, watched Haagen become crestfallen by the arrival of the neighbor’s holiday company. Then she saw Marlon embrace a crying woman—watched him pull back from his shattering point. Haagen and Hettienne chewed dry cereal beside a roaring fire. Marlon passed the stop sign one block from their home.

Monique became an acorn shared by the squirrels in Hettienne’s maple. She became the warmth from the living room fireplace. She sung to Haagen in his mind while his warrior orchestra played their instrument weapons. She peaked out from behind the maple just as Hettienne’s flashlight threw its shadow’s enormity across their snowy back yard. She whispered in Marlon’s ear as he turned off the car in the driveway and stilled himself before joining his children on Christmas morning, Ma famille, c’est ma vie.

“I can’t help myself; I’ve got to see you again,” sounded from Marlon’s stereo before he shut off the car and went inside.

-END-

About the Creator

Matt Keating

Currently working on a six part saga about mystery, murder, and Nature Beings.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.