The Art of Running a Long Con

A Life of Honest Lying

Growing up with a father who was a con man bent my perspective on the concept of wealth and personal freedom. Due to his profession of freelancing for fortune, ours was a complex family life to navigate. Each morning was greeted with an air of uncertainty: Today we retire to Costa Rica from the con of a lifetime? Or today my Auntie Helen will show up on the front porch telling me to pack a bag because I am going to be staying with her for a while. My first question to her was always, “For how long?” and Auntie Helen would just answer, “For a while. Now, let’s get you packed.”

My first question never was, “Why?” I knew why. My father was in jail again. He had been held for questioning so many times (for so many coincidental intersections with a reported theft) that officers from the local precinct all greeted me by first name when they saw me in the grocery store. They would also give me “that look” – the one that had that bittersweet combination of affection and pity. I knew that they were trying to be kind, but I didn’t like it. It made me feel small. And a little afraid that Lady Justice might decide to remove her blindfold and not find it in her heart to allow my father to return to our tiny home at the bottom of Haven Road.

So often was my father en vacances (as he liked to call his stints at the county jail awaiting bail), our neighbors would try to hide their surprise if they saw him out weeding the front flower beds or shoveling snow from the driveway. It was well known throughout the neighborhood that my father’s “vacations” were not spent on some tropical beach of white sand, nursing a mai tai.

He would wave to the neighbors and toss out some benign comment about it being an early spring or the apple trees being plagued by a tent caterpillar infestation. It was enough of an effort to appear friendly, but not so much that they would feel inspired to bring a pan of enchiladas over after one of his more protracted absences. He was good that way – reading people was a requirement in any con man’s portfolio.

You could never say that my father wasn’t of a growth mindset or lacking in the ways of persevering. Whenever he was temporarily detained, my father was not the worrying type; I suspect that he used this time to imagine and scheme his next con. He kept right on dreaming and conning. But that was my father. And the cardinal rule of any con? “Never drop the con. Never.” If I heard my father say this once, I heard it a bazillion times.

True, my father had a hard time holding what some would call a “regular” job, paying the rent some months, and keeping up with the utility bills. But he was also a good and tidy neighbor, a volunteer at the public library, and a disciplined diarist. He swept the front porch and steps every morning before enjoying his morning cuppa. He said that the Art of Sweeping was his preferred form of mediation for starting his day.

He preferred to hang our laundry outdoors on a long line that ran from a corner of the house to the back shed. My father would tell me that he was bringing Nature’s Molecules to my dreams, as he shook out the sheets above the mattress when remaking my bed. I loved my father for these flights of whimsy. I was twelve or thirteen before I stopped believing in the fanciful ways of Nature’s Molecules and their power to influence my dreams. Also, by that time, I found myself sorely wishing that they were real and could soothe my growing worries about my father’s unsteady future.

My father was a devotee to his Morning Ritual. Upon awakening each morning, he would set the kettle to singing and get out a tin of what I liked to call his Dirty Sock Tea. This tea of choice – Lapsang Souchong – was a rare variety of tea favored by a fictitious fur trapper from some Michener novel – a book that my father had thoroughly enjoyed while being detained by the county.

Getting through one of Michener’s epic novels, front to back, must have meant that it had been a lengthy stay at Auntie Helen’s for me . . . all over some inexplicable mix-up that involved some costly tennis bracelets. The confusion was cleared, as was my father – so much so, I recall him receiving an apology from Mrs. Darrington over the inconvenience of my father having had to endure the unpleasant rigors of such unpleasant confinement.

That was my father. He could spin a yarn that cast a web of pure fantastical illusion. His was an art form of assessing and pivoting, bobbing and weaving, ducking and standing tall. As he used to say to me: “Life, as in music, is all about tempo and timing.”

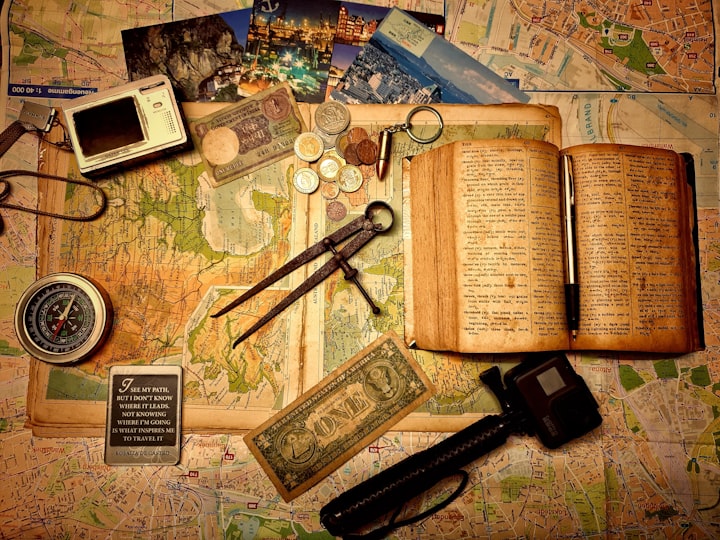

My father’s writing time in the morning was sacred. He would sit at the oak library table that was tucked into a cramped corner of our living room and record his musings and his observations of life in one of his beloved black Moleskines. It’s the only journal he ever used for recording his daily ruminations. He said that he liked the way the compatible volumes lined up like “an anonymous regiment of friends” on the pine shelves that were fixed to the wall above his desk.

Upon filling the pages of yet another of his black journals, he would affix a hand-lettered Roman numeral to the spine of the completed volume with a dab of rubber cement to indicate chronological order. He was thorough in this way. The uniformity of those black-spined volumes was soothing for me – providing a sense of stability and consistency.

He used blue Ball jars full of marbles and old coffee cans filled with rocks and shells to serve as book ends for his Moleskines. One year for Christmas I found a set of bronze bookends cast in the likeness of noble wolves calling to the moon. He loved these bookends and used them to replace two of the rusty cookie tins that were filled with nails and screws. He said that looking at his volumes of ideas made him feel like he had something in common with the likes of Einstein, Tesla, Leonardo, and Michelangelo.

As a child I couldn’t quite make the leap of comparison between these historical greats and my father, but when I was older and he was gone, I could understand the similarities of their respective mindful endeavors.

Not being the type of man to ever open a savings account or to contribute to a retirement fund, his words and his ideas were his ultimate wealth. I admired this about him. His prosperity lived inside him, and it was accounted for through his words and ideas. He possessed a brilliance that went undetected by most. He never consciously did things that would make him appear to be erudite or intellectual; it was more that he just had this simple elegance about him. He would sip his malodorous tea, pick up his Mont Blanc (surely procured from some job), and scribble away in his black Moleskine – devising ways to make enough money to, at the very least, take care of the bills that month.

The fact that I knew most of his marks is noteworthy. Not in a personal way, but I would have recognized their photos in the newspaper or could have picked them out of a lineup. It meant that my father was not one to stray far from home for one of his cons. I would suspect that this had a lot to do with me being enrolled in public school and needing some form of stability.

But I knew, deep down, that he had what Auntie Helen called Itchy Feet. He was one of those rare individuals who actually owned an atlas and kept it on a tall stand near the fireplace. He would page through it and, paraphrasing one of his favorite movies, he would say to me, “Ceci, we’ll always have Costa Rica.”

My father had an ongoing love affair with Costa Rica. I was never completely sure as to why Costa Rica specifically. There are so many places in the world. Still, out of loyalty to his dream, I wanted to go there, too. Like something organic, it grew within me. It was something safe to share between us that didn’t involve the law, court hearings, the next con, or Auntie Helen. It was our surreal getaway when the power got turned off or when life was feeling a little overwhelming. I was glad that we had this to share – someplace beautiful and far away and exotic and secure.

Some of his cons were get-rich-quick schemes that were largely implausible, along the lines of bumping off an armored car or robbing a bank in a nearby city. And some were more realistic, like “expropriating” a rare piece of art from Mrs. Bank’s collection. This is what my father referred to as a Backyard Job, which required many mornings of sipping tea and many pages being devoured by his Mont Blanc.

Mrs. Banks, being one of the richest and stingiest-souled women in town, was what my father called an Inevitable Target. People like Mrs. Banks were Crows – the kind who just had to crow about their riches and who were merely opening the door for an inquisitive Magpie to swoop in and relieve them of some of their responsibilities. Put this way, it did seem like a bit of a toilsome burden to have to protect a collection of fine art. If my father could help Mrs. Banks out by alleviating some of her responsibility? Well, it made sense to me.

After all, it all came down to being a voluntary exchange, didn’t it? This is the hallmark of any con: an element of agreement. True, it might not come out as being exactly mutually beneficial. And some could even say the final outcome might benefit my father at the expense of one of his marks. But I must say that this wasn’t my father’s raison d'être.

You see, my father wasn’t one of those hustlers who would ever lift a pocketbook out of a harried mother’s shopping cart or swipe an heirloom piece of jewelry from a coffined corpse at an Irish wake. His thievery involved more than . . . well, stealing. For my father, it was more about the plan, the plot, and the persuasion . . . for lack of a better word. There was a finesse to his schemes. An elegance with a social motivation.

My father’s absolute favorite style of con: he loved an elaborate plan that would “shift ownership” from someone who he said “didn’t possess a social conscience.” This is how he explained it to me when I was nine and cast me as a “cooperative element” in one of his schemes. In other words, I was his shill for that con.

The end goal of this particular venture was to shift ownership of a vintage Rolex from Mr. Sweeney’s wrist to my father’s suit jacket pocket. This shift took place during what amounted to my father suffering “an unfortunate and mild infarction.” All of which involved my father looking sorely ill while lying on the sidewalk in front of Mr. Sweeney’s jewelry store. My role was to exclaim and create a ruckus, a performance that my father said could have earned me an Oscar.

After the fracas had calmed (and my father having made a miraculous recovery), we were afforded an escort home by an off-duty ambulance. I still remember the vivid details of that ride: my father sitting up on the gurney chatting with one of the paramedics about the delicate art of intubating a patient. How my father knew about this stuff, I’ll never know, but the medic seemed to appreciate my father’s appreciation of his skills and abilities.

Once home, my father explained that Mr. Sweeney had been caught on a security camera leaving a box of infant kittens behind the Walmart. It all tumbled into a pile of good sense once I learned this. The kittens had been rescued by a local shelter after receiving an anonymous phone call by “a concerned citizen.” How my father learned of Mr. Sweeney’s heartless crime, I still don’t know. But that was my father. The grapevine always seemed to creep its way downhill on our street and wind its way straight through the front door.

My father didn’t celebrate when we did manage to pull a con with a healthy return. He didn’t like to rehash any of the details or laugh at someone else’s gullibility. I asked my father, “So, it’s like you’re Robin Hood, right?” He laughed and patted me on the shoulder. “Now I don’t see any remote version of Little John around here, do you?” Then, changing the subject, “So, what do you think is the most common breakfast food in Costa Rica?” I grew to learn that Costa Rica was a ringer – his go-to for changing the subject away from the con and toward something a little more wholesome.

My father was in the midst of what would have been Volume XXI at the time he recorded his last entry in his Moleskine. The pine shelves were filled with the evidence of a life well documented. The black volume lay there on his desk, his Mont Blanc on top of it. I picked up the pen, and a sob escaped me. I could feel the weight of his love and his words in that pen. It spoke of all that he had communicated to me in the ways of life and justice and mercy and advocacy. Yes, my father was a con man, but he was a wise and generous man, too – one who knew how to love and to live with a clear conscience.

I opened the journal and there, tucked into the back pages, was a letter to me in his unmistakable calligraphy. Clearly, he had planned for this day. His letter talked about how much he loved me. He said he wanted to apologize for the unconventional life he had offered me but, in the next sentence, he quoted Shakespeare’s line, “To thine own self be true . . .”

My father had a way about him. He was what I would call a dreamer, but he was also a schemer. He had an angle on always trying to pull off the right con – one that would set me up for college or for life or for whatever I hoped to accomplish in my early adult years. He used to say that he never wanted me to fall under the burden of a mortgage or high interest credit card debt or student loans. He wanted me to be able to live my life on terms that would rest easy with the soul.

I loved my father. Yes, he took advantage of people and stole from them. He always reassured me that he only took from what he called the “unenlightened” rich and never the “kind” rich. And I believed him. And I figured that our own definition of rich must have been relative to us being able to pay the mortgage on our tiny house. Still, I had to hand it to the old man. I have never seen anyone work as hard to make less in the end.

Which is why I was utterly bewildered when I read his letter. Wanting to feel some sense of nearness, I read the words aloud. I had to stop a few times, my eyes blurring with tears, to absorb what it is he had to say. He told me that he loved me and that he had achieved at least one thing in life: to leave me what he called a bit of a nest egg and that all I had to do was follow the steps outlined in the following pages.

My father’s instructions were simple: Go to Volume XX, turn it upside down, and shake out the pages. I did so and ten crisp $100 bills shook from the pages, along with a note instructing me to do the same for Volume XIX. Ten more $100 bills fluttered to the floor around me, along with a note directing me to Volume XVIII.

I continued backward through the volumes. Volume I also held its share of $100 bills, along with an envelope that contained a legal-looking document and a photograph of a tiny weathered house on a bluff overlooking the ocean. I squinted at the document, my mind scrambling. There, deeded to my name, was our tiny dream house. Overlooking the beach. In Costa Rica.

I felt numb, wondering how my father could have managed to pull this off and without letting on. The accompanying letter detailed that he had bought the property after the Larkspur venture – a recent con I remember well with me posing as a cleaning person to gain entrance. The money? He had been tucking away bills in these volumes for my entire life.

I gathered the bills and counted them. Yes, there were 200 of them. $20,000. Enough, my father assured me in his letter, that would provide for me until I could find my sea legs in Costa Rica and start earning an honest living on my own.

I sat there filled with grief and shock . . . and certainty as to what my next move would be: get online and make a one-way plane reservation to Costa Rica. Pack up the house and specify which boxes should be shipped to my new adventure. Donate the rest of the house’s contents to the Humane Society’s thrift store. Give the Prius to Auntie Helen. Ask Dot, the neighbor who liked to grow a carpet of English daisies in her front yard instead of lawn, if she wanted our gardening tools. I could hear my father’s voice, “Give and ye shall receive.”

The release of all that he had tried so hard to provide for me during my childhood left me feeling full . . . and richer than I could have ever imagined feeling. I knew that all of my father’s Moleskines would travel with me, along with the Singing Wolves bookends, no matter how much it cost me to ship them.

My father had given and provided and loved and created ways to keep us balancing on that knife edge called life. No predictability, no reliability, and no guarantees. And I could see this now. There is never any certainty in life. I laughed thinking of how we used our Prius, successfully, for a getaway car when trying to get away from a particularly angry mark or the time we pulled off the melon drop with a bottle of 3 Buck Chuck from Trader Joe’s. That thrifty bottle had netted us enough to pay the phone bill and the power bill that month.

The irregularity that these experiences lent to my childhood could have been an exercise in chaos. But there was a constancy embodied within my father’s love and how he wanted his daughter to live life on her own terms. “Figuring out what motivates you to do so is the trick,” was the last line he ever recorded in his Moleskine. Whatever “to do so” meant, I wasn’t sure. Still, his words comforted me. Dad, I love you. I’ll see you in Costa Rica.

About the Creator

Kennedy Farr

Kennedy Farr is a daily diarist, a lifelong learner, a dog lover, an educator, a tree lover, & a true believer that the best way to travel inward is to write with your feet: Take the leap of faith. Put both feet forward. Just jump. Believe.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.