My father died at the age of 85, just shy of the new millenium. He was in good health, but something inside of him made him simply "check out." He stopped walking, as if it were an arbitrary decision, and he was admitted to the hospital for which he had once served as Chief-of-Staff dozens of years earlier. It was as if he was simply "finished"; as if he had accomplished everything he had wanted to do; as if there were nothing left to live for.

Was it depression? Might Prozac or Zoloft have saved his life? He probably would have spurned any therapy, for his mind seemed to be made up. It wasn't resignation; it was more like what comes after fulfillment.

We are cast into our lives rather rudely, and then we bumble our ways through as best we can. Our choices direct us past the many forks of our paths and we are forced to live out our decisions. If each fork in the road had a crystal ball sitting atop it, there would be no regrets. However, lucky are those who have few regrets anyway.

They say that at the moment of death our lives flash in front of our eyes. Forks create the twists and turns--along a timeline of the better part of a century. That's a lot of history. My father had about a week to replay everything, as it turns out. Then he died.

FIRST-GENERATION IMMIGRANT

His father, Lucas DiLeo, came to the USA from Italy at age 9. He married his 14-year-old wife when he was 22, the age of his betrothed not uncommon at the time. They were both from a small town near Palermo, Sicily, Lucca Sicula. More than likely, the families knew each other and the arrangements had been made before they had arrived separately in the U.S., both of them ending up in the New Orleans area.

He sold cars while going to night school to become a pharmacist, thereafter opening DiLeo's Pharmacy, which also had a sweet shop.

Big Pharma wasn't then what it is now. More like Li'l Pharma. Basically, aspirin companies, Carter's Little Liver Pills, and the potions and salves from the patent medicine era. The legitimate medicines were compounded, mixed, and even invented on the fly as per the ailment being treated. Mortar-and-pestle stuff.

Together, Lucas and his wife, Rosalie, raised 6 children, two of whom became medical doctors, two others, dentists, and two others did well outside of medicine. Lucas' first born was my father, John Lucas DiLeo, born in 1914.

Lucas was a man who swore by "education first" and, coming to America penniless with a third-grade education, he was educated through several tiers of schooling, ultimately able to run his pharmacy and put six children through college, and four of them through professional schools after that.

SECOND-GENERATION

That education-first sensibility rubbed off on my father, who forbad me to work during my studies--wanting nothing to distract me. For him, it was he who had to do the work so that his children could concentrate on their education.

We were all raised Catholic. He was in several Catholic organizations and lived his faith of Christianity, often doing surgeries without charge on those who had fallen on hard times. He and my mother had been the baby boomers from the first World War and then survived the Great Depression. (We came along as the baby boomers of the second World War.)

They were together that Sunday morning when their generation's version of 9/11 happened--Pearl Harbor. My father was rejected by the military because his eyesight didn't pass, although he did countless complex chest and abdominal surgeries during that time: it just took eyeglasses!

My father was a surgeon, and back when he trained the specialty was all combined into the label, "general" surgery. Since that time the subspecialties of thoracic, neuro-, and vascular surgery have split off. But he did it all because that's what the surgeons did then.

Although ophthalmology, otolaryngology (aka, ear, nose, & throat), and urology seceded from "general surgery" in 1937, the rest were all still combined in the surgeon's program while my father trained. As such, he did gynecological surgery, neurosurgery, chest and abdominal surgery, and even orthopedic and brain surgery. By the end of the 1940s, other subspecialties became their own official disciplines and my father retreated to those he liked best--chest and abdominal surgery.

The best doctors, today, still lead two lives--the "stay-on-task" objective professional and the personable, caring, and empathetic version of that professional. My father was able to lead both types of lives, knowing both the fine line between them and the time it was prudent to blend them with some degree of overlap.

Back then, medicine was much more of an art. A doctor had to make a judgment based on only an appraisal of a patient's history, symptoms, and physical exam. True, these three elements are still crucial today, but we now have tests that can give a perspective with a list of possible diagnoses. AI is creeping into the strategy.

Back then, the physician was limited to his or her (but usually his) own delineation of the perspective. It wasn't so much a case of "the" diagnosis as "my" diagnosis. (Today, there are more women training to be doctors than men.)

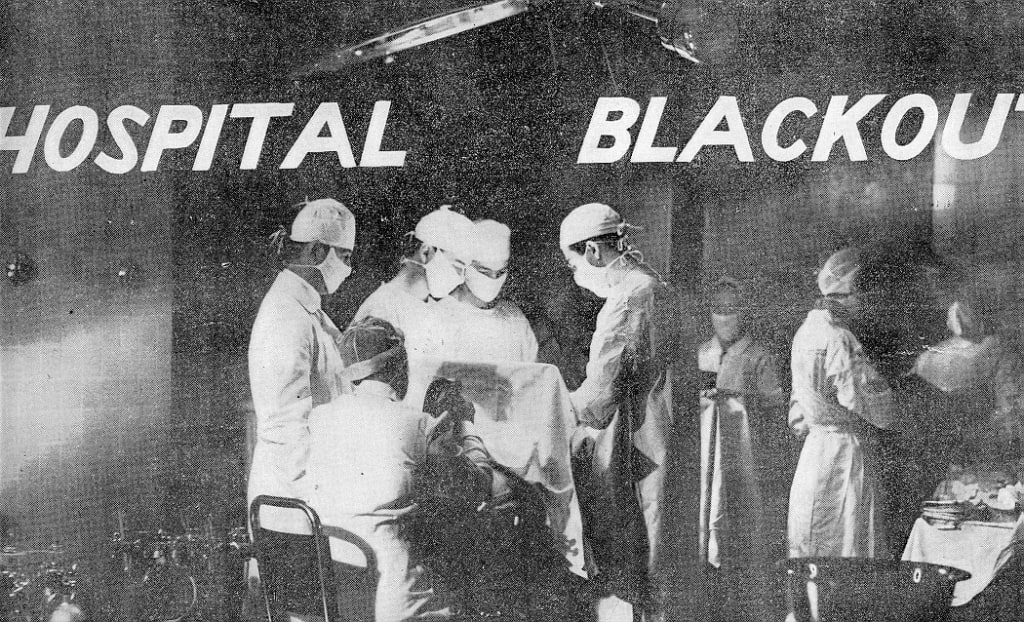

I have a newspaper picture he's in, performing surgery at Charity Hospital during World War II (see title picture, above; he is the solitary surgeon on the right). The story describes surgery during blackouts in preparation for an attack on New Orleans from the Gulf of Mexico: translated, spotlight surgery while dodging illusionary Nazis.

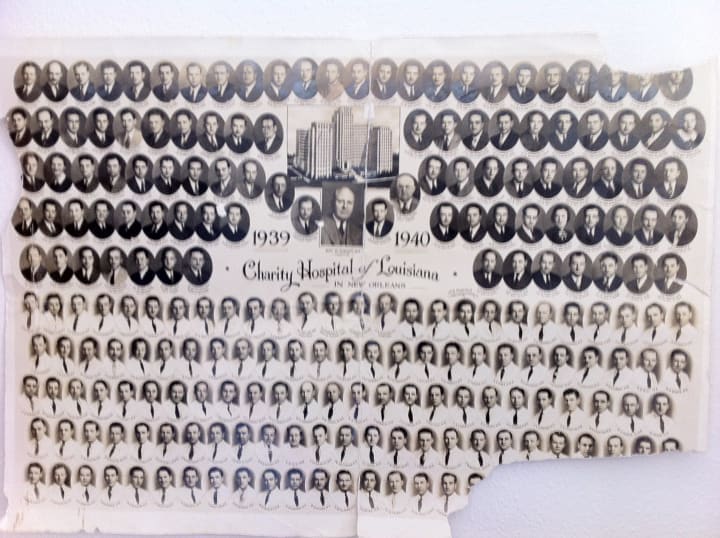

CHARITY HOSPITAL

He did things the hard way because there was no other way to do it. When doctors needed a urinalysis, they would visit the patient's bedside with the glass urine container. Whe they wanted X-rays, they had to find a gurney and roll it to the patients themselves, first stop before X-ray and then the return to bedside. There were no hospital rooms, per se; there were "wards," with 12 beds each.

Charity Hospital in New Orleans was only one of a network of "free" hospitals "for the people," populist politician Huey P. Long build during his governorship. However, the one in New Orleans was the flagship--"Big Charity."

Back then the Charity surgeons often operated with the windows open. They had no antibiotics, since penicillin was only due to arrive in a few years with WWII (just in time!). The only "scans" at the time were X-rays and physicians' eyeballs. There was no plastic in medicine. (There was no pastic!) The IVs were glass bottles with glass tubing. The syringes and the needles were used over and over, sterilized repeatedly by boiling in water until they became dull. There were no pills for sexually transmitted diseases, only painful injections.

Nuns ran the hospital like they ran their elementary schools--tight. In fact, there was no need for security. No one crossed the Nuns. New Orleans was a predominantly Catholic city and the Nuns were the bosses.

Lectures involved demonstations in "the pit," with terrified students and residents fearing being called on by the professor below. Stress was part of the training, and when the "expert" below pointed a finger at you, you had to have the right answer, lest he lay into you--in front of all of your peers--with a diatribe on you as the cause of needless morbidity and mortality (the famous "M&M").

He finished his residency after serving as Chief Resident in his final year. Once his training had been completed, he hung up "his shingle."

And waited and starved.

The older surgeons in circulation were not eager to dilute their incomes, and his practice slowly grew only by word-of-mouth, operation-by-operation on the patients on which other doctors wouldn't operate.

He never became one of them. If someone needed his skill, he was there for them. While it's always nice not to work for free, this never held him back if someone came to him with a gallbladder that wasn't going to fix itself or a lung cancer that became the evil curveball in his or her life.

As he got older, he stopped the chest surgery, decreasing the load of life-and-death situations he had to manage. Eventually, he stopped operating altogether and found happiness seeing Medicaid patients in the inner city as a retirement job. By the time he was 85, he was completely retired, satisfied with his work over the years. At least once a week in my own practice I saw a patient who asked if he was my father, telling me all about their mom's or dad's colon cancer surgery or that appendectomy (before the laparoscope was even a hint of an idea in some surgeon's mind).

My father's complication rate was extremely low in a world lacking the modern safeguards against infection and other post-op concerns. And he did it without CAT scans, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, or the hundred times as many types of blood tests available now. He retired without a single lawsuit, but also, he never sent anyone to a collection agency. He knew Drs. DeBakey and Cooley and the famous Dr. Ochsner, who popularized the link of smoking with lung cancer and spearheaded the polio vaccine movement, from which his own grandaugter died.

He crossed the halls of Charity Hospital from the "white" side to the "colored" side, back and forth, over and over, failing to see the dividing line that the segregationists had drawn.

Charity Hospital died the day Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans and the levees broke. Today it sits deserted as a monument to old medicine and asbestos walls.

THE REST OF THE STORY

My father saw his share of celebrities that came to the Blue Room at the old Roosevelt Hotel, most of whom stiffed him on the bill. When President Gerald Ford came to New Orleans, he was the surgeon selected to wait in the prepared surgery area should the President need emergency surgery. (At the time, I was in medical school at LSU, and I begged him that if that were to happen, could I please be the President's medical student. I told him it would be an excellent learning experience. "C'mon, Jerry, cough for me." Fortunately, the President left New Orleans unscathed.)

He was Chief of Staff of Hotel Dieu the year its new replacement hospital was built, thereafter transferred in ownership as University Hospital (LSU). There have been a lot of changes in medicine over the years, and the amazing thing is that I had seen medicine change more in my last ten years of practice than my father had seen during the six decades after his graduation from medical school. In today's world of the Internet of Everything, with total medical knowledge doubling every 77 days, tomorrow's surgery won't be your father's--or even last month's.

He'd been through fifty-nine years of marriage, sixty-tw0 years of being a doctor, and fifty-four years of fatherhood. He had paid for seventy years' worth of education for his children as well as served as clinical faculty at LSU providing education for many doctors, all voluntarily.

LESSONS FROM MY FATHER

I learned many lessons from him, some of them articulated, others demonstrated by acts of kindess in lieu fo words. Nevertheless, they stay with me as maxims by which to live long and well:

- It it needs to be done, it might as well be you. Let the others stand by and just watch.

- You can't fight a dirty fighter unless you want to be a dirty fighter, too. Sometimes you just have to let the bastards win, but it's is a Pyrrhic victory.

- Always be a gentlemen; you can't go wrong, even when you're fighting a dirty fighter.

- The future is just as much a part of your life as your past, so move on.

HAPPY FATHER'S DAY

Every Father's Day sends a wealth of tradition, history, and pride through my bloodstream and my soul, and his legacy rekindles in me, again, always when needed, the important things of life--because all the rest is bullshit.

When your life is flashing in front of your eyes, you get to choose the things your remember, so it's a nice send-off.

About the Creator

Gerard DiLeo

Retired, not tired. In Life Phase II: Living and writing from a decommissioned Catholic church in Hull, MA. Phase I: was New Orleans (and everything that entails).

https://www.amazon.com/Gerard-DiLeo/e/B00JE6LL2W/

email: [email protected]

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.