Donkeys and Wolfs

When putting words together, I often dance around ideas, trying to make them sound eloquent with exaggerated metaphors to communicate some deeper value. But that was not how I was raised. As a child I was taught by my grandfather to be direct, treating the truth like a cudgel. To have no shame when bashing people with the bluntness of my tongue.

So, in the style of his lessons, I share my story about him.

My biological father is a stranger. There is not much to say about him. We met once when I was an adult, but it was an awkward mess. You can’t reattach a dead limb with duct tape. There is no love or hate, and he was mostly forgotten till I wrote this paragraph.

Now, my grandfather was the man I knew from the beginning. When I look back at growing up, there is this haze. When my first formation of awareness began, my grandfather was there. The clouds of my mind would part and there was my Pappous (Greek for grandfather) jutting out like a mountain peak.

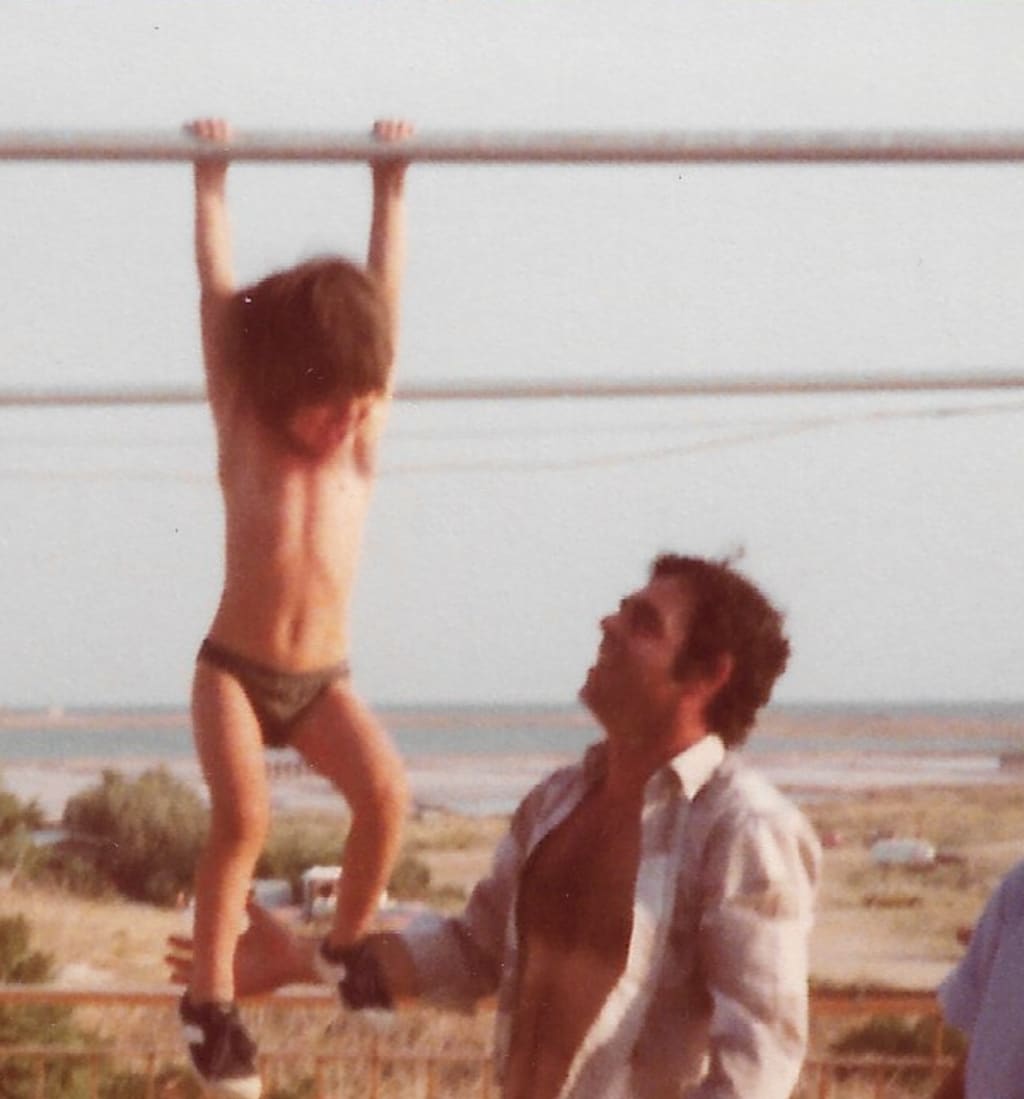

My memories of Pappous are not linear, they are just groupings of pictures and emotions. I only have one or two memories of my biological father, but many of my grandfather. The tough old Greek wore his collar shirt open to air out his gold medallion. He seemed so fierce in my mind; he could wilt a man with his stare. There were hard edges to every part of his face and body. He was lean and dark featured with thick eyebrows and always clean shaven. When dealing with people, he never used gentle words. He was not a coddler.

“Your daughter is getting fat,” is all my grandfather said when he noticed my mother’s belly. My mother told me she had kept her pregnancy a secret, so in his ignorance, the old Greek told her to eat more salads.

Even with all my love for him, it would be a lie to say he was a good man. He was an alcoholic, violent, misogynist, who now seems irredeemable, but no male figure had ever loved me so selflessly. He installed in me a rebel streak that liked to bend rules and the confidence to challenge authority. These are virtues that help protect who I was as a person through all the trouble and difficulties instore for me in the future.

His faults were many, for example, he never called women by name unless he had a lot of respect for them, otherwise he only called them “gynaika” which translates to “woman”. Even to my grandmother, to who he was married for decades.

“Woman, get me coffee.” Is the most loving thing I ever heard my grandfather say to my grandmother. Maybe he had a love for her in his own way, but how would I know? Being a frequent adulterer, he didn’t seem very committed to my Yiayia. He was a rock of old-world masculinity that refused to recede despite the tide of a changing world.

We only had a few short windows of time in our relationship. He was with me until I was five, and then later when I was eleven, but when I look back at family photos, I have more pictures with my Pappous than I do with my mother. He took me everywhere, we did everything together, and we shit-talked constantly. He used to love it when I called him “buster”. When I didn’t get my way, I’d threaten him with “I’ll punch you in the nose buster!” and then make a fist at him and he would laugh till tears came to his eyes. Which is also the only time, save one, that I saw him cry.

He gave me the first taste of being manly. Gave me my first sips of ouzo and beer to put hair on my chest. Putting cigarettes in my mouth for photo ops, to show how “tough” his grandson was. He wanted me to be a rebel like him. I would walk around with my shirt off, mimicking how he would hold out his chest when he walked.

Life was straightforward back then. Even at four, I would confidently wander around and do what I liked. I would catch snakes and frogs, even dead rats, till I filled my pockets. I would bring them home just to make my mother and grandmother scream. This would entertain my grandfather and he would reward me with the biggest belly laughs.

There are no illusions about it. I know I was a terrible child. My Pappous had encouraged it. He loved his grandchild, who was brash and wild. But for all the love he shared with me, he seemed to measure out an equal helping of hate to the world around him.

My uncle told me a story about when Pappous was a young man. The only thing of value that he had was a donkey. He would take the donkey through the garbage dump and scavenge what he could from here and there. He would load up the donkey with some found treasures and then wander around from village to village, hoping to find someone who would want to buy one of the salvaged treasures. One day, the donkey refused to walk, so he gave it a beating right in the middle of his village to motivate it. People laughed and yelled at him. Feeling humiliated, he pulled out his knife in a fit of rage and stabbed it to death while it screamed and bayed. The scene was so horrific they kicked him out of the village.

He was a man possessed by his passions. In one moment of anger, he killed the thing that had kept him from starving. When I hear cruel stories about him, I’m reminded that as a child I only saw the best parts of him. All of us are followed by the shadows of our wrongs, but somehow, I missed the large shadow that loomed behind him. But I know he loved me and that it blessed me to have him in my life.

We used to drive back and forth between Greece and Germany a lot. One time we went on a little retreat somewhere in eastern Europe. Driving through the woods late at night, we came upon a parking lot filled with people. They were all waiting around, drinking. It was a well-lit parking lot surrounded by thick black woods. It was like a scene from a cult movie. Everyone was silent and waiting for something. They paid us no heed and did not acknowledge we arrived. It felt inappropriate to talk, so I just stood next to my grandfather and waited with the others.

Slowly, as the moon crept into the sky, the woods exploded with howling. We couldn’t see them, but out in the woods were a pack of wolves howling at the moon. The howls were so loud and close it was like a trumpet in my ears. Young men in the parking lot tried to make jokes and laugh at the howling, but I could tell they were unnerved by it. Everyone just stood still, listening. It was like a seance where everyone was keenly focused on the long mournful howls. It was one of the most beautiful things I had ever heard. The howling was so powerful and penetrating that the hair on the back of my neck stood up, and a feeling of excitement spread across my body, making my fingers and toes tingle.

The howls were unapologetic and wild like my Pappous.

After a time, when the howling died down, we walked through the parking lot to a large monastery. The building had no electricity, and I could see candles in the upper window. It was quiet, solemn, unassuming. Perfectly contrasting with the wild howling. We had been standing just across the parking lot from it and I never saw it till we turned to go in.

We walked up to the monastery to get a room for the night. From my understanding, the monks had a tradition of letting travelers stay overnight. We stayed in a small but elegant room that had crucifixes on the walls and handmade furniture. I remember thinking about how the room seemed fancy, only there was no bathroom in the room at all, and there was a problem. I needed to go.

When I told my grandfather, he uncharacteristically looked worried. He told me we couldn’t leave the room at night because the monks walked the corridors chanting, also we were specifically told not to leave the room till morning. But the urgency was great, so I looked around the room and saw a giant copper pot. I told my grandfather I could just pee in the pot, but he responded no. He came up with the idea for me to pee in the hallway around the corner from the room, but I had to watch out for the monks. As my Pappous and I conspired he explained that I would have to go alone. I could imagine it would be easier to explain that I was just a small child who took it upon himself to pee in the hallway instead of having a full-grown adult coaxing a child to do it.

This heinous act of sacrilege brought a smile to both of our faces when we looked at each other.

The only advice he gave me was, “Don’t get caught.”

At that point, I could feel it in my gums. So I happily ran around the corner and peed on the wall in the hallway. It was such a relief, and even though I could hear my grandfather calling from the room in a whisper, I just continued to desecrate the holy hallway for what seemed like an eternity.

While peeing, I imagined the monks walking around barefoot, turning the corner, and one of them slipping in my urine and doing a “Peter Sellers” like fall to the ground. It made me laugh aloud. That really got my grandfather’s attention. He hissed and whispered even louder. When I returned to the room, I went right to bed. I had planned to stay up and listen at the door for the chanting monks, but it had been a long day. Before going to sleep, I asked my grandfather if we could see the wolves in the morning. He told me no in a low, menacing voice, “The wolves would eat up a little boy like you,” and we both laughed.

That night, I imagined myself sneaking out of the monastery. I would creep out past my sleeping grandfather and the chanting monks, and out into the woods to meet the wolves.

Thanks to my Pappous tutelage, I had no fear of men, or priests, or wolfs.

“What would happen if the wolves ate me?”

I pictured it in my mind; the wolves chomping on my fingers and toes, the sound of snapping when my bones would bend and break in their jaws, and I thought it would be a wonderful way to die.

I would be a legend. The boy that parents warned other little boys about. Maybe I’d be in the newspapers.

“This little boy didn’t listen to his grandfather, so the wolves ate him.”

It felt tragic, but there was no cruelty in it, no evil. It strangely felt moral to me. There was a difference between the cruelty of a man stabbing a donkey to death and wolves eating a little boy. I did not understand the totality of conflicting morality in my mind.

For all his evils, my Pappous was the closest thing I ever had to a father. After separating from him and moving to the United States my life became unstable, I went from a broken home to foster care, a process I’d repeat a few times. I was caught in an unpredictable current where predators picked off the weak. I often wonder who I would be without that wild streak my Pappous instilled in me. Sure, he taught me that getting into trouble was fun, but the real trait I learned was independence. The independence to not let the worst of the world bring out the worst in me. Through all my troubles I was able to stay myself and not become a slave to the wrongs inflicted on me. Even though we are different in most ways what influence he did have on me changed my life for the better.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.