A Bit of What You Fancy

... always does you good.

I am an almost-adult — I have a job and several longterm pot plants, if not a flat or a boyfriend — and yet when I saw Joe Hardy again I felt like a nervous teen. My god, I told myself, you’ve got a Masters degree and a thriving Peace Lily, you should be able to get a grip. I knew that the right thing to do was go and comfort him, but I was too proud. Instead, I moved only to push aside my Grandma’s white, net curtains, spying on him like some ageing member of the Neighbourhood Watch.

Joe was rebuilding the low drystone wall which hems the house where his Grandma, Betty, lived until a few months ago. His face had hardened and grown angular as if flesh had been carved from his cheeks. It was the way he carried himself though which had changed the most. There was something considered in the way he surveyed the pile of stone before each move, as if he were strategising a one man game of chess. Gone was the quick, nervous boy I remembered.

*

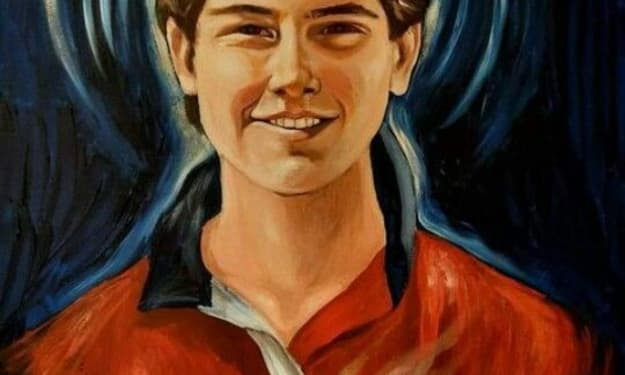

Between the ages of five and fourteen, both Joe and I were packaged off for the summer holidays to our Grandmas’ houses in rural North Yorkshire: Joe sent alone on the train from somewhere near Cornwall; myself, hand-delivered in the car from just 30 miles away, a bow tied in my hair like a carefully wrapped parcel. I can see Joe now as he was; the image is tinted golden, drenched in liquid summer sun; he is nine, maybe ten, and he is stood waiting for me outside, dressed in short shorts, his legs hanging down like two pieces of white string. His head flicks up and down the village like a young buck ready to bolt. He was nervous. The first few days of summer he always was, as if it took him a few days to realise that the only monsters around were the ones he conjured in our games.

Soon we were inseparable: joined at the bloody hip, laughed our Grandmas, as we skittered past them lounging in the garden; best friends forever, we said, sealing our vow in tomato ketchup, stolen from the pantry and smeared across our palms; what time do you call this, they said, when we finally tipped back home. Not that they really cared what time it was. There was supposed to be a routine, or a totalitarian regime as Betty called it: a timetable sent by her son to ensure Joe’s good behaviour, Church attendance and academic success. Time though was not something our Grandmas kept; as for religion and school, they were far too old for that. They spent their days sprawling in candy-stripe deckchairs, savouring punnets of sweet fruit and even sweeter village gossip. At some time in the early evening, they swapped to drinking red wine, draining their glasses as the light drained from the sky. They were probably only in their early 70s, but to us they were ancient, cased in thick, leathered skin, their bare limbs gnarled like branches.

One evening, I stood outside with Joe, watching Grandma tip back the last of her wine. She caught me looking. Her finger wagged in the air. ‘A bit of what you fancy does you good,’ she said, ‘Don’t let your mother tell you otherwise.’

Betty cackled and snorted involuntarily. She had a deep, dry laugh from years of smoking, and, as my Grandma used to say, years of laughing at the shit life had sent her. Betty's hand lay on my Grandma’s. ‘Modern women we are,’ she said, still laughing, ‘You can tell your mother that.’

It must have been much later, I think perhaps the summer we turned thirteen that Joe stole a bottle of red and two glasses from his Grandma’s pantry. I followed him, carried along as I always was by his games. We took the plunder to our den: a bush in the copse behind his Grandma’s house. Once a prime piece of childhood real estate, the space had become too small for both of us; we squashed side by side: arm against arm; leg against leg. Joe stuck the glasses in the ground; they titled tipsily towards each other.

The cork was an unexpected hurdle. Joe valiantly tried to prise it out with his fingers and then tossed the bottle, angrily, petulantly, to one side. It rolled towards me. I picked it up. 'Merlot,' I said, pronouncing the final 'T'.

Joe didn't reply, and I looked at the image on the label. Even now I remember what it was. The outline of two young women: long skirts, wide brimmed hats, thin arms and legs like delicate wineglass stems. I looked up at Joe. ‘What was this all for anyway?’

Joe pressed a broken stick into the muddy ground, working it round and round. ‘Nothing. It was stupid.’

I dug my bony elbow into his side. ‘Go on, what were you planning?’

I was surprised to hear the tension in his voice. ‘Just leave it would you.’

I wouldn’t leave it, and in the end Joe snapped like a twig breaking under foot. ‘OK, OK, it was meant to be a first date.’

I laughed, saw he was serious and rearranged my face. It was my turn now to look away. 'It still could--'

'Just forget it would you. This doesn't count.'

I looked up at Joe. We stared at each other and then somehow we were kissing. We pulled away, and then we laughed, tipping back into childhood and onto the muddy ground behind us.

The rest of that summer we seesawed between friends and something more. We would kiss in the corner of some sun scorched field, and then the moment would slide away from us, and we would be running again in pursuit of some make believe game. Only at the end of summer, did we seem to slow down. I remember dawdling along the dirt track that leads out of the village. It was the last day of summer, and Joe scuffed his trainers along the ground, walking at half speed.

‘How can going home put you in such a bad mood?’ I asked.

Joe shrugged, and kicked up a cloud of dust from the track. ‘It’s hard to explain, I just can’t be myself back there.’

I always wished I had asked him what he meant.

The next year Joe didn’t come to his Grandma’s house. I asked Grandma of course, casually, slyly, as if the idea of him had surfaced out of nowhere, like an unexpected cloud on a bright summer’s day.

Grandma stopped mixing the bowl of butter and sugar in front of her, and, for once, she seemed to not know what to say. ‘Pet, I don’t think Joe’ll be coming to visit anymore.’

‘But why?’

Grandma was evasive, and, with a teenager’s special brand of self-centred egotism, I thought that the problem must be me. I took it as a personal slight; I wrote in my diary: I hate Joe Hardy.

*

The afternoon after I saw Joe again, I sat with Grandma in her faded living room. We each had a glass of wine. Grandma’s conversation hummed in the background: Peter over at the farm says; Mary over the way says… In the end I had to interrupt. ‘But Grandma how are you doing? You know how’re you holding up?’

Grandma’s hands trembled; her voice stayed steady. ‘I feel her loss everywhere, but it was her time.’

I had guessed the truth by then, but I did not know how to phrase it. ‘She was a 'good' friend, wasn’t she?’

Grandma paused. ‘The best.’

‘How did you meet again?’

I knew the story well, but I liked to hear Grandma tell it. Two newly widowed women separately escaped to the country and met at the limited wine section in the village store. They argued over the last bottle of Merlot. Each of them had spent a lifetime sharpening their tongues on good for nothing husbands; it was clear that neither of them would win. Grandma sighed and looked down at her hands, finishing the story on a long, slow exhale: ‘The only answer was to share the bottle.’ Grandma nodded towards the armchair I was sitting in. ‘She sat there you know that first evening. It’s where I poured her her first glass. We talked for hours, and god she made me laugh, that is until…’

I smiled. ‘You went upstairs?’

Grandma laughed, and the conversation took a turn I had not wanted. ‘Joe was good to her in later years you know,’ said Grandma, ‘He’s lived here on and off for the past year. He was the only thing that stood between her and a nursing home.’

I made a non-committal noise.

Grandma was undeterred. ‘You know pet, it was his parents’ who kept him away. They found out about Betty and I, and god knows the rot they planted in his head.’

‘I saw him today,' I said, trying to cover my surprise.

‘How was it?’

‘Well, I mean, I watched him through the window.’

Grandma tutted. ‘Why don’t you go and see if he's free now. Take over a bottle of wine?’

Grandma cajoled and pestered, and in the end I gave in. In her pantry there were dozens of bottles of red wine laid out flat on the shelves. It was clear that Grandma had kept her weekly subscription in the months since Betty’s death. The bottles had built up like tributes at a shrine. I ran my fingers over the cool glass, tracing the curve of each bottle. I took one in my hand and then put it down. At the back of the shelf I recognised THE bottle; the same two women, only this time did I notice that they were holding hands. Merlot, I said to myself, pronouncing the 'T' for the first time in years.

I walked back into the living room where Grandma was sitting. ‘Are you sure about this? I’m meant to be here to keep you company after all.’

‘I’ll be asleep in ten pet, you go and enjoy yourself.’

I hesitated. ‘I don’t know, what good will it do?’

Grandma picked up the bottle on the table beside her and poured herself a second, small glass. She smiled her sideways smile. ‘A bit of what you fancy always does you good.’

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.