Why Study Literature?

And What Not to do When Studying Literature

Misconceptions about Studying Literature

One of the popular misconceptions about studying literature in school is the concept of ‘the right answer’. You have probably had teachers who have tried to teach one reading of a literary text as though it were the gospel truth, whilst others who proclaim that ‘there are no wrong answers in studying literature’. Both of these viewpoints are unhelpful.

The first method - that there is an ‘authorised version’ of reading any canonical text is unhelpful because literature is designed to be a ‘living’ text. What is meant by this is that its interpretation varies depending on the person reading it and the values and morals and worldview that they bring with them. Take, for example, Frankenstein. A reader in the early 19th century may read the text as a warning against the rejection of religion over science, as they would likely have had some form of religious upbringing (although we must avoid generalisation - there are always exceptions to this). Another reader from this time, may, however, view Frankenstein, as a reflection on the wave of revolution that was sweeping across Europe at this time. A Marxist reader may view the creature as a physical representation of working class man (as he was stitched together from the bodies of a number of working class men). His violent destruction of the bourgeois Frankenstein family, then, could be seen as symbolic of the Marxist revolution that Marx claimed was one day inevitable. A feminist reader may point to the sidelining of female characters and their violent deaths at the hands of vengeful men as symbolic of their position within a patriarchal society. Furthermore, the whole novel could be seen as May Shelley (the author) communicating directly with Margaret Saville (the recipient of Waltons letters) as a story about men and their need to prove their masculinity. There are any number of other ways the text can be viewed, and as society changes and develops, new readings emerge all the time. Consider, for example, the cyborgisation of the human body, the fluidity of gender and sexuality, and human cloning and consider how these ideas may alter our impression of this 200 year old story. An ‘authorised’ reading of the text clearly will not do. This is true of any text, and it is, in fact, the whole point of literature - it encourages to think about ourselves and about the world in which we live; in other words - the ‘human condition’ (more on that later).

So why then is the view that ‘there are no wrong answers in literature’ also unhelpful? There are two reasons for this. The first problem with this is that there clearly are wrong answers in literature, and this stems from one source - misreading. If you claim that Frankenstein killed Elizabeth, or Macbeth pushed Lady Macbeth or that Animal Farm was an allegory about the Nazis, I am afraid you need to read a bit more closely. Closely linked to this is taking a controversial theory and stating it as fact. For example, ‘Frankenstein created the monster because he wanted a doppelgänger to kill Elizabeth as he was secretly in love with his mother.’ Now, even if you can find evidence that might support such a view, you still need to express this as a tentative suggestion of a possible reading - interesting, but by no means certain. Stating such theories as fact, again, suggests that you don’t understand the difference between a fact and a theory and this will be regarded as an error.

The second reason why ‘there are no wrong answers in literature’ is unhelpful, is the mistake some critics make in differentiating between authorial intention and reader interpretation. For this I will turn to the words of J.R.R. Tolkien who, frustrated by the number of critics who tried to second guess his intended meanings when writing The Lord of the Rings, stated:

“I think that many confuse applicability with allegory, but the one resides in the freedom of the reader, and the other in the purposed domination of the author.”

In other words, you might think when reading The Lord of Rings that the One Ring was an allegory for the hydrogen bomb, but Tolkien certainly wasn’t. Literature is not riddle with a specific answer, it is not code to broken. Whilst it might be interesting to know what a writer may have been thinking when writing a novel, it is virtually impossible to know precisely what they meant - they probably don’t even know themselves, as much of the meaning behind the ideas will be subconscious. Furthermore, it probably isn’t all that important - the text is there for all to see, it is up to reader to decide what to make of it. We must always avoid, however, forcing those interpretations on the writer themselves. As a side note, it can sometimes be interesting to consider what a text reveals about writers themselves, but we must approach this cautiously. Writers often adopt personas within novels and picking through the narrative voice and the authorial voice within a novel can be as dangerous as tiptoeing through a minefield (not literally of course).

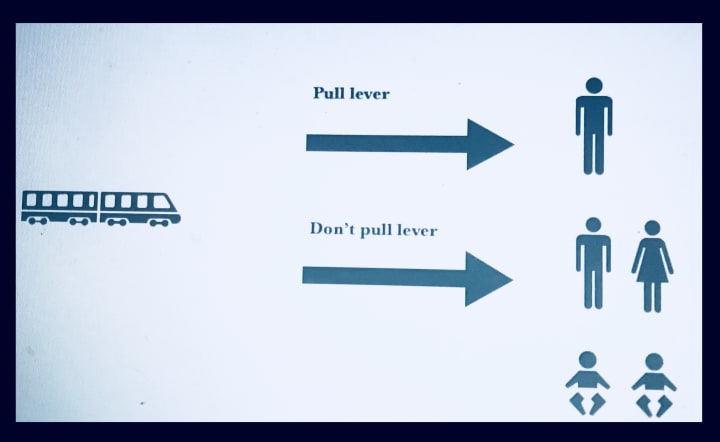

Literature rarely presents us with straightforward situations and opinions about themes and ideas can vary from reader to reader. Consider the examples presented by moral dilemmas. For example, in the ‘trolley dilemma’ a train is hurtling towards a group of two adults and their children who are walking on the track. They cannot see the train approaching but you can. Next to you, there is a lever; if you pull the lever you can switch the direction of the oncoming train and divert it away from the family. However, there is a problem - if you change the direction of the train to the alternate track it will hit a single adult walking on the other track.

Often, the first reaction to this dilemma is that the answer is obvious - pull the lever and save four people and sacrifice one. However, how do we know that this is definitely the right decision? Maybe the person that would be killed might have discovered the cure for cancer. Furthermore, there is a difference between being a bystander to a tragedy occurring and making an active decision to divert the train into the path of someone - are we not effectively making a decision to kill someone, regardless of the reasons behind our decision? Might not the family of the dead man disagree with our decision? Might they not claim we have committed murder? In this case there are no ‘right’ decisions, only an awful choice which we must live with.

Literature can present us with similar moral issues. Consider, for example, Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure. Several moral dilemmas are presented within this play, the most memorable of which is the one that Isabella is confronted with. Isabella, who is seeking to become a nun, is given an opportunity to save her condemned brother’s, Claudio’s, life (he has been convicted for sex outside of marriage). However, in order to do so she must have sex with the ‘acting’ Duke, Angelo (clearly a man who does not ‘get’ irony). Isabella is, therefore, given the choice of preserving her honour, but condemning her brother to death to do so; or, saving her brother’s life and losing her honour, as well as sacrificing her vocation as a nun. To a modern, and largely, secular audience, the choice might seem fairly clear - her brother’s life should come above her virginity (although, again, this is highly debatable and depends greatly on one’s point of view). However, to a seventeenth century audience, this would be a very difficult choice. In agreeing to Angelo’s demands, Isabella is committing a sin, and, if she is doing it at the behest of her brother, whilst she may be saving his physical body, she would be condemning his eternal soul to damnation. We may scoff at these notions as outdated theological arguments, but surely the point is that Isabella, and most likely the majority of the audience at the time, would believe these notions. Furthermore, there are problems from a modern perspective. To suggest that Claudio’s life is more important than Isabella’s virginity is, in itself, problematic. Claudio is a convicted criminal, according to the laws of the day - we may argue that the law is harsh, or that it should be abolished, but, according to the laws at this time, Angelo has not done anything that the law does not give him the right to do. Therefore, his punishment is lawful, and even Claudio admits to his own guilt. Isabella, however, is being blackmailed into consenting to being raped by Angelo (in that she is agreeing to sex under duress - sexual coercion); how can we say that choosing this could ever be the ‘right’ choice? Furthermore, Claudio, knowing the potential consequences for her life afterwards, even asks her to do it, which makes it clear to us that this is no heroic character. Under these circumstances, is it really such an easy choice? Shakespeare is clearly attempting to create a much more complex moral question than might appear on the surface, and throughout the play we are frequently asked to question the moral choices that most of the principle characters in the play make.

Significantly, the play’s ending is left open-ended, surely an indication to the audience by Shakespeare that there are no clear decisions to be made when considering moral choices. It also makes audience members question themselves about their own values, particularly as our opinions about characters and situations change and develop as the story unfolds. This is one of the main reasons to read, and study, literature - it allows us to learn about ourselves and makes us question the values and convictions we hold, which is a vital part of being a fully functioning human being.

‘It’s alive!’ - Reasons to Study Literature:

‘When you’re working in the money markets, what good are the novels of Wordsworth.’ (Four Weddings and a Funeral)

Whilst the above quotation may make even those with only a passing interest in literature shiver, it highlights a view about education in the arts that is far too common - that while it be nice to learn about fine art and works of literature, it is essentially useless.

Few people express this view about science, because with an education in science you can become a doctor; if you choose to study law, parents will beam at the thought of having a solicitor or a barrister in the family. However, if you tell your parents that you want to go to art school or write for a living and many parents will furrow their brows and internally judge their offspring, as though they had expressed a wish to join the circus. Say you wish to audition for X Factor and many parents will encourage and support, but say you want to become a painter and they will grimace and think ‘why can’t they just get a proper job?’

This, perhaps, says something about our society and the values it holds as important. The reason that doctors and solicitors (or bankers, or civil servants, or teachers) are seen as desirable professions still is because they offer a degree of stability, but are also relatively well paid (although increasingly less so if you work in the public sector these days, but that is a different argument). The highest paid work is often found in the financial sector and the legal sector, and, as a result, are increasingly seen as the most desirable sectors to work in these days. Artists, as the stereotype goes, struggle. It is true that writing rarely earns you a wealthy existence - for every J.K. Rowling there are a thousand struggling to get by; for every A Song of Ice and Fire there are a thousand fantasy novels published each year that few people will have heard of. Before Harry Potter, J.K. Rowling struggled by for years. In other words, people do not go into the arts to make a lot of money (or they shouldn’t). There are easier ways to become wealthy (particularly if you aren’t too concerned about how you do it).

This is, perhaps, why many people struggle with the idea of studying and writing literature - they do not really understand what it is for. Our view of work is that it should be about wealth creation - what makes you the most money. Artists often see what they do in very different terms. This is not, primarily, about making money, it is about the thing being created. That is what has value - not the monetary value that is attached to it.

This is not to say that art is superior to any other form of learning or knowledge. Scientists often pursue their studies not out of a sense of monetary gain, but because they value what they do as important, which it is. Science is about finding ways to explain and/or sustain life; Art is about making that life worth living.

Imagine a world without art. No films, television dramas/comedies, novels, poems, music, paintings, sculptures etc. Our lives would be hollow and empty as well as highly insular. Art challenges us to consider other perspectives, other cultures, other times; it asks to consider morality, our existence, our experience of sentient thought, it engages our emotions - in other words, it goes to the heart of what makes us human.

Therefore, whatever you do for a living, whatever profession you choose to follow, you have a better chance of maintaining your integrity to who you are if you engage with artistic works. It will make you a better human, and allow you to understand other people and different situations better. It will help you to empathise and sympathise. It may not make you better at playing the money markets, but it might help you to understand the consequences of choices that you make.

So if you want to go into the arts as a profession, and someone tells you that ‘there’s not much money in that’, nod your head and reply, ‘you are right, but there is a great deal of value in it.’

‘A classic is a book that has never finished saying what it has to say.’ Italo Calvino

One of the questions frequently asked whenever I taught a text that was pre-twentieth century (Shakespeare in particular), was: ‘what is the point of studying this now?’ It is understandable that a student may not immediately see the value in studying something that is over a hundred years old. After all, what could the concerns of the writer and the character within this novel have to do with them? However, this misses the point of what we study literature for (and this is the fault of the education system, not the student).

Often, the answer given to this question is jingoistic - Shakespeare is great writer; part of the fabric of English patriotism; it is tradition; that Shakespeare is part of the English canon or that he is quintessentially English - part of that mythical view of the ‘green’ England, innocent, pure and heroic. To an extent, there is some truth in this, but none of these are reasons to study Shakespeare, particularly.

Shakespeare was a highly popular writer of his age. Not necessarily the best playwright of the time - Ben Johnson and Christopher Marlowe, at least, have as good claims to that title - he was undoubtedly the writer who most clearly encapsulated his age. His plays spanned two monarchs, and a time of great historical significance to England and they captured the tone and mood of the period in a similar way to that of Dickens in the Victorian period. Shakespeare’s historical plays turned Elizabeth’s Tudor ancestors into heroes - especially Henry V (not strictly speaking a 'Tudor' as such, but used by the tudors to authenticate their claim to the throne), who is glorified for Agincourt and for the speech which Shakespeare gave him in his eponymous play. Macbeth is written shortly after The Gunpowder Plot, and the play details the tragic consequences for murdering a king (kings were seen by many as appointed by God, so regicide was not only treason, but sacrilegious as well). The play can easily be seen as critical of the Catholic plotters' plan to kill James I of England - it was also believed that the real Banquo, one of Macbeth’s victims in the play, was James I’s ancestor. These are merely two examples, Shakespeare’s plays commonly refer to contemporary societal attitudes towards sex, women, marriage, race, politics, war, ambition and so on.

In short, the reason for studying Shakespeare is not because he is a canonical writer, but because he gives us insight into another world - we can learn about laws and attitudes in history books, but Shakespeare brings those concerns to life and shows the effect on people. He allows the audience to share in their emotional state, to become angry at a character’s selfishness or maliciousness, or to sympathise with characters who have had terrible things happen to them. Shakespeare also allows us to empathise, for many of the concerns he presents are still concerns today. Whilst there are not many of us who have been told we will become king or queen by three witches, we probably have faced a situation in which we have been tempted into doing something immoral for our personal benefit. Othello illustrates how a racist society can create tensions within a relationship (also differences in age - think Michael Douglas and Catherine Zeta-Jones or Stephen Fry and Elliott Spencer). Romeo and Juliet presents us with the dangers of teenage ‘infatuation’, which can be mistaken for love, and overbearing and restrictive parents. King Lear is really about old age, madness and legacy. All of these ideas are still concerns today, and at the heart of Shakespeare’s plays, we are told stories about human nature - the fact that they are kings, or aristocracy or military leaders etc. lends them an epic scale, but is largely irrelevant to the central issues.

So in Shakespeare we see that, while the attitudes, values, political systems, societal structures, dress, the language and so on may change, these are plays about human nature and the human condition, and this is something that does not change. Humans are just humans, whatever century they live and whatever position they hold. To return to the quotation at the top of this section, whenever Shakespeare is brought to a new generation, it will make that new generation consider how it relates to them in their world, its similarities and differences, and, most importantly it will ask them to think about those concerns that lie in the heart of it, and probably, think about them differently to the previous generation.

In fact, this is true of all literature - for example, The Great Gatsby is focused on 1920s America, with its excesses and moral hypocrisy. However, it is also relevant today - it focuses on attitudes about status, the position of women, relationships, greed, immigration, the widening gap between rich and poor - all central concerns of our culture as much as Fitzgerald’s. Philip K Dick’s novel 'Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep' (popularised by its film adaptation Blade Runner), challenges the reader to consider human nature and what, precisely, makes us human, particularly as technology develops and changes the human body (consider how often we interact with technology now, compared with how often we interact with an actual person). By seeing these ideas from a distance, and another perspective, it allows us to consider them objectively and philosophically. We also understand that the concerns we may have are intrinsically human concerns - they are not tied to a particular time period or place, but affect all of us, all of the time. Literature teaches us to empathise with one another - to see the similarities between us - so rather than see people in other cultures or other times as different, we see them as being people like us. Their situations and societies may be very different, but they are still human, with the same nature as ourselves.

This, of course, is the function of literature as a whole - to present the reader with something unfamiliar to them and their world and, in doing so, force them to think. If we were to read a book that outlined something similar to our own life it would not be that engaging to us - what could we learn by having our life retold back to us. By presenting us with something unfamiliar, the writer asks us to consider a new perspective, a new way of looking at the world. In doing so, we automatically attempt to find things that we identify with. This then causes us to see similarities in our situation and our life to someone else whose life is different to ours. It makes us more tolerant, more understanding; it challenges us to see the world the way someone else sees it. Literature makes us more sensitive and more understanding and helps us to become the best version of ourselves. So the next time someone says that there is no point reading stories that aren’t true, be sensitive to their point of view, and then whack them around the head with a book.

About the Creator

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.