Why AP Classes Aren’t Worth It

And City College Is

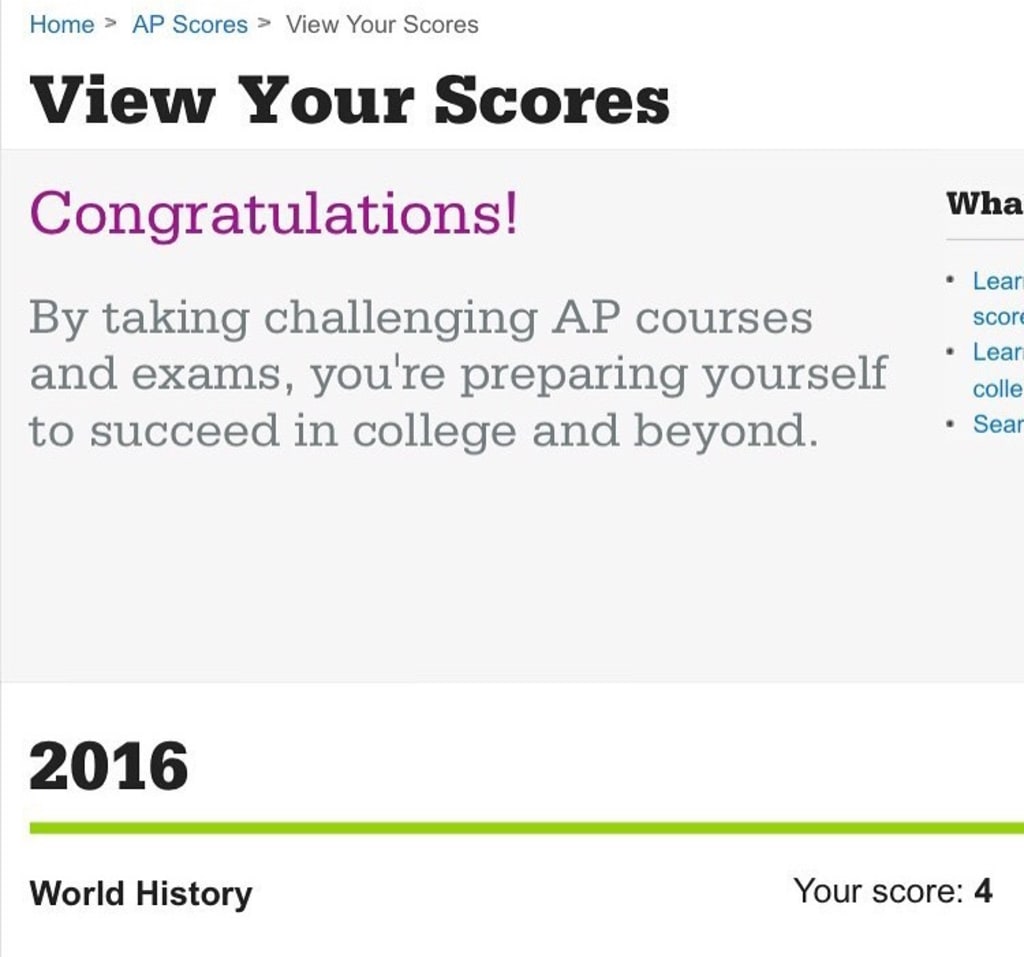

After a full school year of hard work, late nights, and stressful days, many people did not receive the credit they had worked so hard for. Despite the good grades many of them had, they simply did not fit the rubric of the AP® test in the end. I had managed to pass the exam, but I watched as many of my friends and classmates, who in my opinion were more deserving, looked at their score and found that they had not made the cut. In fact only 58.3% of my peers that I surveyed actually passed the test. I found myself wondering what the point of the AP® test was and why we even had to take it. We all had already worked hard for the grade we received in the class, what more was there to prove? AP® classes should be treated as equals to college classes; there should not be more work than college classes and there should be no more poorly conceived standardized tests.

AP® classes are more work than their college equivalents, although they claim to be equal. If so, they should be true equals in work loads and difficulty. Authors of “A Makeover for the Introductory Comparative Politics Course: Revising the College Board's Advanced Placement Program® (AP®) Course in Comparative Government and Politics,” David L. Richards and Neil J. Mitchell, state “AP courses are designed to reflect the college classroom experience, so it was also of interest to know what is happening in introductory comparative classrooms.” This is what should be happening in all AP® classes. They should replicate what real college classes are like and follow the same sort of work pattern. Having taken an AP® class myself, and now taking a city college class, I can tell you that my experience with the two classes are very different. The AP® class was a horrible mixture of high school and all the busy work that that entails that has been stretched to fit two full high school semesters, along with the added stress of important notes and tests. The result was nine months of the same class and constantly being stressed and busy, whereas this year with my city college class I feel more relaxed and have a realistic amount of work to do. Eric Neutuch in “Advanced Placement United States History: A Student’s Perspective” states that his class rushed to get as much information as fast as possible, which resulted in a test nearly every day the first week of school and an average of three chapters of the textbook covered per week. I understand that there is a lot of reading and work in college, but college gives students more freedom to complete assignments in a more reasonable manner. In my AP® class, every chapter had to have notes which had to be done in a specific way to get a good grade whereas in college, notes are usually more recommended than required. In my college class, many of the assignments are more open ended and allow more freedom in writing whereas in AP classes, the assignment usually had a firm answer and followed a strict formula. College classes have a lot less busy work and focus more on student’s learning than its AP® counterpart. If AP® classes are going to truly replicate the college experience then they must have around the same amount of work as college classes.

AP® tests are limiting students who already have proven themselves worthy of college credit. Many students excel in the already challenging class, but fall short on the exam at the end of the year that determines whether or not they will receive the college credit that they worked so hard to obtain. The test forces the students to write in a specific way that may make them sound like they have a strong thesis even when they do not, and if they do not follow this pattern it can cause their thesis to sound weak even if it is strong. As said by Ryan Bloom in, “Inescapably, You’re Judged by Your Language,” “All of the complex linguistic theories of language acquisition and whether grammar is universally hardwired or learned through practice don’t matter one bit in practical everyday living,” using AP® taught English does not equate being more intelligent nor is it always proper to use. Just because a student does not write as though they are an English professor does not mean they are not worthy of college credit, it just means they are writing in a more comfortable and relaxed manner. There is already enough pressure and stress going on during the exam without students having to think about if their sentence structure is perfect for the AP® rubric or if they are using the fanciest word for the simple idea they are trying to get across. According to Wade Curry, Walt MacDonald, and Rick Morgan in, “The Advanced Placement Program: Access to Excellence,” “Most post-secondary institutions grant credit or advanced placement to students with grades of 3 or higher. In 1999, 64% of all AP grades were 3 or higher.” The problem with this is that it is the equivalent of only 64% of all students passing an introductory college class. This number is far too low to represent a class that claims to be the equivalent of a lower division college course, while the percentage of people who pass the class itself more closely reflect this. Kathleen Kennedy Manzo states in, “Mass Appeal” that people such as Mike Riley do not care about students scoring well, as long as they are challenged, although they may want scores to start going up in the future. Students are already sufficiently challenged without the add on of the AP® test. The test should simply be removed altogether to improve the accuracy of a legitimate simulation what college classes are like. Georgi Boorman in, “The Advanced Placement Scam” states that many students that get As and Bs in the class itself and then fail the AP® test. The test is an atrocious way to measure people’s knowledge of the subject because many people simply get test anxiety, have an off day, or just forget things under the pressure of the test. The grade received in the class would be a better representation because it is the compilation of what they have learned and accomplished throughout the year. By forcing it all into a single test that, no matter how long it is, will not be able to cover all the material. Students that are already doing above average in the class should not need to prove themselves any more, especially using a system that is unable to function properly. There is no big test at the end of college classes to decide if you will really get credit, so why should there be one for an AP® class?

Having the AP test at the end of the year makes most teachers and students only focus on preparing for the test, which is the opposite of what the education system is trying to push for. Classes are supposed to be about learning and exploring a topic, not memorizing for tests; standardized, AP, or otherwise. Neutuch states that in his experience with taking an AP® class, the focus of it was preparing for the ‘big test’ at the end of the year and nothing else. His class followed a strict schedule that would get them through all the course material before the exam came around and ended up sucking all the excitement for history out of them with its repetitiveness. I had a similar experience in AP® World History last year where every homework, test, and the in-class work was centered around preparing for the test. Everything we did focused on bringing us one step closer to being ready for the AP® test and I left the class not feeling like I’d learned anything although I passed. In a survey I conducted, entitled “AP® Responses,” 83.3% of participants found that their experience was similar, as they answered yes when asked the question “Do/did you find that your class is/was mostly about preparing for the AP test?” Michael Henry in, “Advanced Placement U.S. History: What Happens after the Examination?” states, “With almost a month of school remaining, I questioned whether my intellectual letdown, and that of my students, was laziness or a normal reaction to the culmination of preparing for a test that had dominated the focus of my class since the previous September.” Preparation for the exam is done to an extent that when it is over, teachers do not know what to do with the remaining time. I experienced this last year as well when in my class after the assessment was over we had no longer had material to cover. If the AP® test was taken out, teachers would have more time to cover all topics and not have an awkward amount of time left at the end of the year. Henry also later states that despite the fact that it is supposed to be a class, not test prep, many teachers only treat it as such. Taking out the AP® test would allow teachers to focus more on teaching the subject and less on teaching for testing. There is no good reason to have the test in the first place and removing it would benefit both students and teachers. Teachers could form a better schedule and go deeper into material while students could enjoy going at a slightly slower pace and not worry about a single test that determines if they get the credit they have struggled so much to get.

Colleges have no reason to fear AP® classes diluting the subject by allowing more students to pass. Colleges will not lose money nor will students be any less qualified than if they had taken it at the college. In, “Is AP Too Good to Be True?” by Justin Ewers, he states that many colleges are starting to wonder if letting just anyone into the class is reducing the quality of the class. However, this is not actually happening; the amount of people who pass has stayed relatively the same throughout the years. According to the College Board© on their page titled “AP Data- Archived Data,” the World History pass statistic for the last six years has stayed around 51% and only fluctuates slightly. I only use World History as a reference point, but glancing at the other subjects I found that the slight fluctuation applies to the other subjects as well. While it may appear that the number of students that pass is going up, this is only because the amount of students that take the class is also going up. The actual percentage of people that pass the exam has not changed and the small nuances are certainly no cause for alarm or suspicion that the quality of the classes is going down. Colleges may also be worried that by accepting AP® credit then they will lose money by not having the students take their classes. Paul W. Eykamp states in, “Using Data Mining to Explore Which Students Use Advanced Placement to Reduce Time to Degree,” that many Universities in California made policies about how they would accept AP® credits based on the assumption that students would use the credit to get their degrees faster, but his look at the data showed that there was little to no correlation between the amount of AP® credits and how fast students get their degrees. Colleges have no reason to not treat AP® classes just as they would any other college class. All colleges should accept AP® credit where the credit is due. They will not be failing in deficit, nor will the students be ill prepared for the classes that they will be taking at the college.

If AP® classes are supposed to replicate college classes and give students an opportunity to earn college credit then it is doing a very poor job of it currently. The way they have it now is far from the mark of matching what the true college experience is and limits student’s ability to learn. The intense focus placed on preparing for the AP® test pushes students away from getting a deeper understanding of the subject matter and only focus on memorizing all the facts that they will be tested on. Even classes that could use a lot of deeper thinking questions to enrich the curriculum are unable to fit it into the busy schedule of constant studying. The pressure to take AP® classes mixed with the low pass rate of most of the exams has resulted in even more stress for students than if they had just gone to city college.

Works Cited

Bloom, Ryan. “Inescapably, You’re Judged by Your Language.” The New Yorker 29 May 2012. Web.

Boorman, Georgi. “The Advanced Placement Scam.” The Federalist 27 May 2015. thefederalist.com/2015/05/27/the-advanced-placement-scam/. Web.

Curry, Wade; MacDonald, Walt; and Morgan, Rick. “The Advanced Placement Program: Access to Excellence.” Journal of Secondary Gifted Education Fall 1999, pp. 17-23. Web.

Ewers, Justin. “Is AP Too Good to Be True.” U.S. News & World Report 19 September 2005, pp. 64-66. Web.

Eykamp, Paul W. “Using Data Mining to Explore Which Students Use Advanced Placement to Reduce Time to Degree.” New Directions for Institutional Research Fall 2006, pp. 83-99. Web.

Henry, Michael. “Advanced Placement U.S. History: What Happens after the Examination?” Social Studies May/June 1991, pp. 94-96. Web.

Manzo, Kathleen Kennedy. “Mass Appeal.” Teacher Magazine March/April 2005, pp. 11-12. Web.

Mitchell, Neil J. and Richards, David L. “A Makeover for the Introductory Comparative Politics Course: Revising the College Board's Advanced Placement Program® (AP®) Course in Comparative Government and Politics.” PS: Political Science and Politics April 2006, pp. 357-362. Web.

Neutuch, Eric. “Advanced Placement United States History: A Student’s Perspective.” The History Teacher February 1999, pp. 245-248. Web.

Walker, Medea. “AP® Responses.” Survey. 17 November 2016.

“AP Data- Archived Data.” College Board. research.collegeboard.org/programs/ap/data/archived. Web.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.