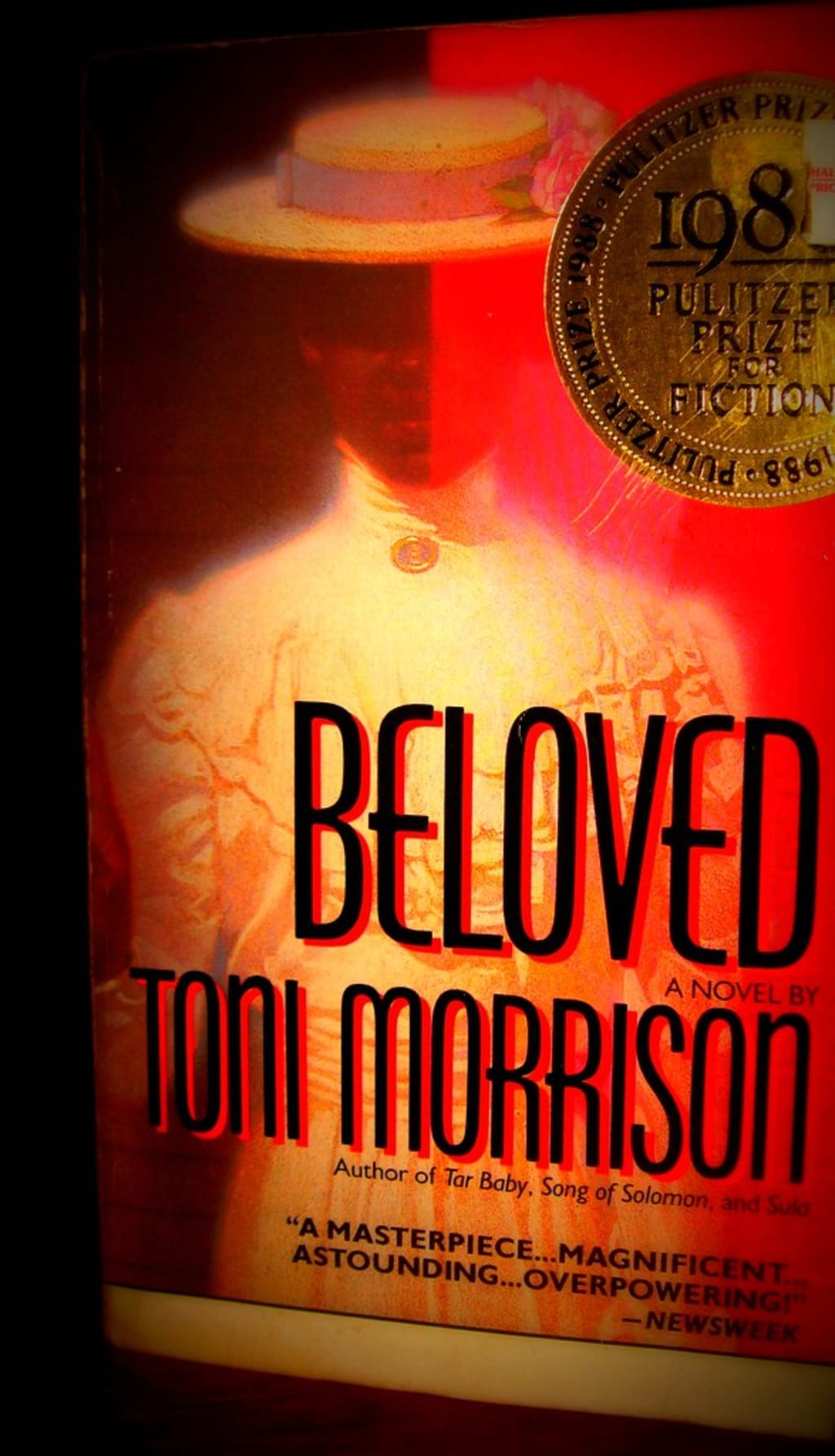

The Motif of Comparing Characters to Animals to show the impact of generational racial trauma in “Beloved” by Toni Morrison

Morrison shows the impact of dehumanization on people’s thoughts and actions by including this motif

In nature, it is survival of the fittest. Only the strongest beasts will make it out alive, and the most vulnerable will die in the wild. Humans are believed to be better than animals; they have self restraint and control over their choices and fates. Therefore, when people are compared to and treated as nothing more than animals, it strips away their humanity and disregards their inherent worth. In the novel Beloved, Toni Morrison includes the motif of comparing the characters to animals to show how being dehumanized consistently can alter one’s core beliefs and their actions, and how dehumanizing people can cause them severe emotional trauma.

When our insides are altered, our outsides reflect that, which includes how we react to certain situations. The most notable way this truth is reflected in the novel “Beloved” is through the actions of the protagonist, Sethe and the animalistic diction Morrison displays when describing these choices. For example, “She thought it would be enough, rutting among the headstones with the engraver, his young son looking on, the anger in his face so old; the appetite in it quite new.” (Morrison 5). The key word in this excerpt is rutting, which is a term used to describe sex between certain animals. The word rutting is used again in the next paragraph, showing that Morrison wanted the reader to make this connection. This shows that Sethe believed the exploitation she chose to endure in order to get the word Beloved written on her dead baby’s gravestone reduced her to an animal, and her compliance to being treated as nothing more than that and being used sexually stemmed from her consistent abuse and dehumanization while she was enslaved at Sweet Home. This dehumanization is what brings her to kill Beloved, specifically when Schoolteacher makes his pupils list off her animal characteristics. “In order to prevent her own child from undergoing this listing, she slits her baby's throat, convinced that this is a better fate than being written into the order of language, which could "Dirty you so bad you couldn't like yourself anymore. Dirty you so bad you forgot who you were and couldn't think it up" (B, p. 251). The loss of identity that Sethe fears at the pen of Schoolteacher is, in her mind, worse than death.” (Hefferman 3). She also described how hummingbirds pierced her head cloth with their needle beaks and beat their wings when she recognized the Schoolteacher's hat, and she flew to get her children to kill them (Morrison 192). Flew shows the pure instinct she acted out of and the metaphor of hummingbirds shows the insistence and urgency she felt to save her children from living her past. She truly believes she did the right thing, yet Morrison’s purpose is not for the reader to agree with Sethe, despite her being the protagonist. This can be seen when Paul D, a former enskaved person who was also at Sweet Home and her current significant other, says “You got two feet, Sethe, not four,” (Morrison 194). It is significant that this statement comes from him and not a white person because he is not saying this to make her believe she is subhuman, but to show her how completely and thoroughly she has been changed and how her actions resemble the animals she was compared to most of her life in slavery. This statement makes clear one of Morrison’s intentions for including this motif.

One could argue that what separates humans from other species is the ability to have complex emotions, but with that comes with the ability to have complex emotional trauma. Paul D, for example , was deeply traumatized after having a bit in his mouth as punishment. He describes how having the iron pressed to his tongue and not being able to stop it reduced his worth in his eyes permanently. “I was something else and that something was less than a chicken sitting in the sun on a tub.” (Morrison 86). By having Paul D compare and then demean himself even lower than an animal shows how much being dehumanized damaged him. This is not the only time Paul D describes his existence and himself as worse than animals, and he does this even as his trauma becomes progressively worse. After he had the bit in his mouth, he was sent to a prison camp in Alfred, Georgia. At this camp, he was forced to perform oral sex on white men, work, and stay in a cell that was a box in the ground. “The box had done what Sweet Home had not, what working like an ass and living like a dog had not: drove him crazy so he would not lose his mind.” (Morrison 50). The comparisons of his previous life experiences to those of asses and dogs shows just how much the prison camp broke him because that made him feel worse than less than human. This perspective Morrison is trying to display is how brutal the treatment of black people was in the novel and the scars it left on those who experienced it and their loved ones. “She makes us pay attention to history, not as an already-written story condemning us to act and suffer in roles assigned to us by a damaged and damaging past, but as an unfinished process and a working through of traumatic events and daily, repeated violences.” (Jesser 1).

Being brutalized like nothing more than beasts is a reality that black people have faced since the beginning of America, and it has traumatized them and made them believe things about themselves that aren’t true. While this novel shows the dehumanization of them during and directly after slavery, Morrison’s use of this motif paints a picture that still shows racism has not ended. There are still black men being assaulted by prison guards as they are incarcerated at a disproportionate rate, black women and children are more likely to go into or be forced into prostitution than any other racial group, and black mothers are still forced to make inconceivable choices in order to protect their children. The use of this motif shows how generational trauma has impacted the black community, and even though we have come a long way since 1856, it is evident that we are not nearly far enough.

About the Creator

Angie Seminara

reader. writer. artist. advocate. musician. fire enthusiast.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.