Where's Your Toe?

Who's Responsible for the Footprint of Your Carbon Shoe: You, or Adidas?

Shopping for Shoes

If there is one thing I absolutely, positively, 100% can’t stand to do, it’s buy new shoes. I don’t know why, but the thought of walking into a Target and heading for the shoe section makes my heartbeat rise and my palms sweaty. I must have had some kind of bad experience as a kid which I’ve since blocked out of my memory. Probably waiting endlessly for my picky older brother to decide on a pair that he liked. When I do buy new shoes these days, which is never more often than once a year, I grab the first pair that is 9 ½ and buy it. I definitely do not try them on. My mom’s standing over my shoulder in my mind’s eye: “Try these on Eric. Try this pair. Oh, how about this pair? Test it, Eric. Walk around a bit. No, farther than that. Where’s your toe? Is that your toe? Are you sure? Where’s your toe?”

At the end of my dang feet, mom!

(The carbon footprint of one shoe is about 12 kg of carbon dioxide, according to Adidas.)

Footprints

I’m not a huge consumer, is where this is going. I don’t have the disposable income to subsidize a commodity-heavy lifestyle, I don’t really fetishize much other than books. And energy bars. I do really get a kick out of energy bars. But other than that, I live modestly. I certainly don’t own a car or even Uber that much.

(“Ride-hailing companies are responsible for nearly 70 percent more carbon pollution than trips they displace” - The Verge)

For this reason, I’ve always been intrigued by the idea of the individual’s carbon footprint. It is a useful idea: to think about the cost of fuel of any given commodity or service, and how they add up. I do believe in the value of thinking about the carbon footprint of one’s own lifestyle. There are other kinds of footprint calculators too: water footprint is a big one for us in Arizona. Land footprint too. Waste footprint. Et cetera.

The idea of the carbon footprint was originated by a couple of smartypants named William E. Rees and Mathis Wackernagel back in the 90s. They conceived of a metric like this: how many Earths would it take to sustain the human population if every human had a lifestyle equivalent to yours? Which I think is interesting. And quite different from how we use the term “carbon footprint” today.

How did the notion go from a metric used by ultra-nerds to a household term?

Oh, the Irony!

A PR campaign by British Petroleum in 2005 introduced the carbon footprint to the popular imagination. It encouraged people to be mindful of their impact on the environment and their usage of carbon-based fossil fuels. They made it kind of fun. Almost like a personality test. “Hmm, what are my habits? Oh, such lovable habits! Maybe I can carpool once a week and feel better about myself!” I mean, we’re still doing writing challenges about it 16 years later. If you’re reading other entries, you’ll probably come across all kinds of interesting and clever tricks to reduce your carbon footprint. And that’s great! We should be doing that. But we should also be thinking about the history of the concept, and about how responsibility is shared.

Drill Ya One

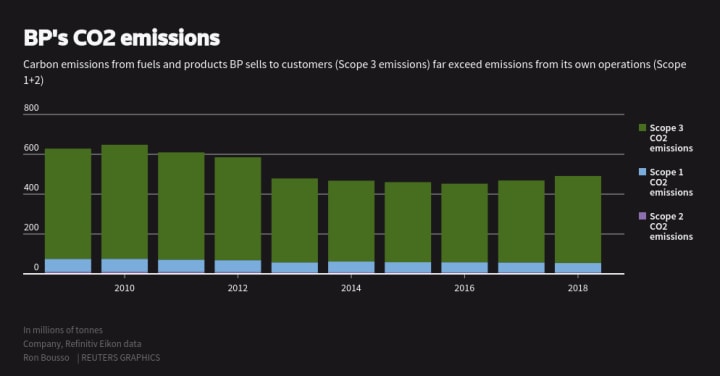

While we were having fun with the carbon footprint calculator, BP was drilling away. Nobody made them do a carbon footprint test. In 2005 they were producing more carbon emissions than ever before. The 2008 crash hadn’t happened yet, renewable energy was still a nascent industry, world economies were growing. Oil, of which BP constitutes one of the major barons, took the largest share in the US fuel mix. (China, trying to catch up with the US, still had coal as its largest share of the fuel mix in the early 2000s).

So this is the question we need to ask ourselves. It’s not a rhetorical question, it’s a real question. What is the value of us little people figuring out our carbon footprint?

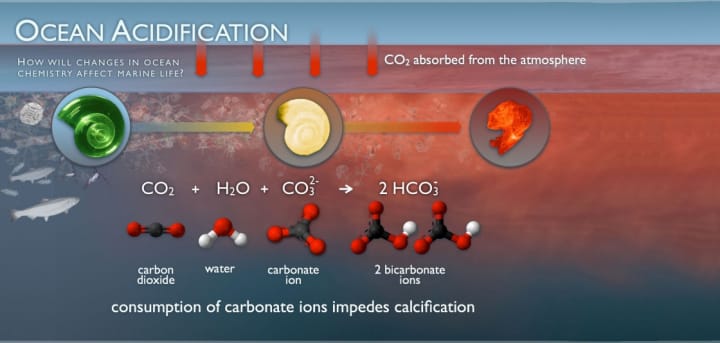

Ocean Acidification

Surprise, surprise: what we do on land affects the sea. Our oceans absorb 30% of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. One result of this is that pH levels of surface waters have decreased by 0.1, which may not sound like a lot but is really a lot. The reason for this is that when carbon enters the water, it doesn’t just sit in there like an emulsion. It chemically interacts with the seawater. The CO2 combines with the H20 to create a weak acid. So “acidification” of the ocean is actually what’s happening.

There is literal acid in the sea.

I remember watching a movie about sushi. Jiro Dreams of Sushi. If you haven’t seen it, you should, but make sure you have a sushi restaurant close by because after you watch it you’re going to want to eat a cartload of sushi.

(The environmental consequences of eating a cartload of sushi.)

At one point Jiro, the world-famous sushi maker and protagonist of the documentary, laments to the camera about the declining availability of certain kinds of ocean fish. He says that as a creative chef, he can work around not having perch or mackerel or eel, etc. But what happens when there is no tuna left? You can’t substitute for tuna. Overfishing is the main cause of declining numbers of many fish species including tuna, but overfishing isn’t the only threat they face.

There are many reasons why our oceans are in danger. And a sick ocean will have larger ramifications than just ruining sushi, although if you’re anything like me, that alone would be bad enough. And it helps to think about sushi specifically, because one of the greatest obstacles to meaningful behavior change is the difficulty of conceiving of concrete consequences.

Sand in Your Toes

Humans like to go to the beach. There are many rituals involved with going to the beach. Putting on sunscreen. Pitching umbrellas. Fitting into bathing suits. Gazing at the horizon. Getting a kick out of the Fata Morgana effect if there are boats at the edge of sight and the angle of the sun is perfect.

One ritual that may go unnoticed is the taking off of shoes.

A thousand people go to the beach, a thousand people plop down in the sand and unlace their Adidas. Plunk them next to the cooler. Enjoy the feel of sand between toes.

We approach the glittering altar of the shore with bare feet, like venerators approaching a temple. I think there is something deep down inside us that knows that you can’t make a carbon footprint with bare feet. You have to be wearing Adidas.

This is how I balance the idea of personal responsibility with corporate responsibility. You can’t focus on one and leave out the other. We do have personal responsibilities. We can choose not to buy Adidas, and buy a shoe from a company with a smaller footprint. We can buy less in general. We can ride a bike to work. We can develop a lifestyle that reflects our values. But then what?

Then What?

Are we reducing our carbon footprints in the futile Kantian hope that, as merely average people, the changes we make in our lives must surely be echoed by the billions of average people around us? The action we take, we take because we wish and expect that it become universal law? Or do we make these changes because we want to wash our hands of everything? When the tuna run out and veggie sushi (ugh!) takes center stage, we can say, “not my fault!”

When pH levels in the sea drop to the point of mass extinctions, will it comfort us to know that we adjusted our carbon footprint down?

If corporate action is not demanded, it is not taken. Every time you enact some change in your life to reduce carbon footprint, send an email to your representative expressing your support for renewable energy. Investigate reforestation efforts in your community. Get angry at BP, send them some emails (this may feel futile, but I am convinced that bad people need to and ought to hear that they’re bad as often as possible).

Yeah But What is the Author Doing?

“All very well and good,” you think, reading this article which at times has strayed dangerously close to smug indignation, “but what changes are you making?”

I think the best strategy for personal change is divestment. Divest yourself from the forces of environmental destruction. And since the health of the ocean is so closely intertwined with what we do on dry land, any reduction in our carbon emissions helps the sea in some infinitesimal way.

- Don’t buy Amazon. Just don’t. It takes a few minutes at most to find alternative online vendors. Don’t break your Amazon rule, either, once you’ve made it. One exception leads to others. Hint: buy from a black-owned online bookstore. Even better: don’t buy online.

- Don’t buy gas. This is the biggest one, and such an unwieldy imperative that it really isn’t advice. It’s just me reminding you that this is probably the biggest change you could make, should you find yourself ready to make it. I ride my bike everywhere, because I’m lucky enough to live in a town where that is feasible. My mom and dad live in Phoenix, Arizona, where personal cars are the only way to commute. My dad this year is considering taking the leap into electric vehicles. A city big enough to mandate a personal vehicle likely has enough charging stations to make an electric car a real option. Hint: keep a log of how much gas you buy every month. If you can even just buy less, then you’re doing good.

- Eat less beef. Agriculture, particularly animal agriculture, is a big contributor to emissions. Cattle specifically. If you can cut out red meat, that’s amazing! If you happen to be someone who really, really loves beef, even simply eating less of it can make a difference. Hint: this may be an unpopular argument to make, but hunting one's own red meat is a hundred million times more ethical than eating factory farmed beef.

- Don’t eat grocery store sushi. A big contributor to the overfishing pandemic is the massive proliferation of sushi across the world, increasing demand for tuna and other commonly eaten fishes. The introduction of sushi into grocery stores is probably the most conspicuous result of Americans discovering they love sushi. Don’t be a part of this. Save sushi for when you want to go to a sushi restaurant. Simple as that. Hint: make a “sushi night.” Once a month, once every two weeks. It’ll increase your enjoyment and lessen your impact.

- Research Corporations. Don’t let BP trick you! It’s not you that’s f*cking up the world; it’s them. But they don’t want you to know it. They want you to think it’s your fault. So research what corporations are doing or not doing to reduce emissions. Hint: https://www.cdp.net/en/info/about-us/what-we-do

- Watch Finding Nemo. I love this movie. I think it’s the best Pixar film. It depicts the diversity and beauty of ocean life the way that it really is when left to its own devices and not messed up by humans. This is what we are aiming to protect and restore. Don’t forget it. Hint: research Pixar’s emissions! You owe it to Nemo.

Under the Surface

I used to be afraid of swimming in the sea. Unlike a bath or a swimming pool or even a lake, the surface of the sea is utterly opaque. Who knows what scary stuff is just under the surface ready to grab my ankle and yank me down?

But the things just under that acidified surface aren’t our enemy. They need our help.

I guess what I’m saying is this: a carbon footprint looks like a shoe sole. We need to get back to a footprint that shows your toes.

So, as my mom would say: where’s your toe?

About the Creator

Eric Dovigi

I am a writer and musician living in Arizona. I write about weird specific emotions I feel. I didn't like high school. I eat out too much. I stand 5'11" in basketball shoes.

Twitter: @DovigiEric

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.