What is a Solar Storm?

The current cycle of solar storm activity is set to peak in 2025. Scientists disagree whether the end of days is upon us, or it’s all just a storm in a teacup.

The current cycle of solar storm activity is set to peak in 2025. Scientists disagree whether the end of days is upon us, or it's all just a storm in a teacup.

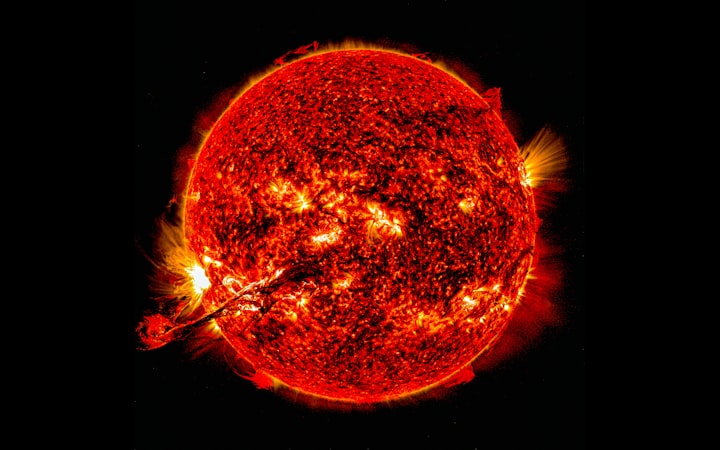

It all starts with the sun. That glowing ball of light in the sky is actually a 4.5 billion-year-old yellow dwarf star in the centre of our solar system. And it's huge and hot. The diameter of the sun is around 1.4 million kilometres, and its core heat tops 15 million °C.

The sun is also an incredibly active place. It is a ball of hydrogen and helium that's held together by its own gravity. Nuclear reactions at the sun's core create the heat and light we experience on Earth - about 150 million kilometres away.

Radiation carries this energy outward from the sun's core where it bounces around the radiative zone for 170,000 years or so. The energy eventually makes it outward to the convection zone, where the temperature drops to a chilly 2 million °C. This forms bubbles of hot plasma that move up onto the sun's surface.

This process can get pretty wild. Electromagnetic radiation eruptions in the sun's atmosphere - known as solar flares - can be incredibly powerful. Solar scientists classify solar flares according to their strength, much like the Richter scale is used to classify earthquakes.

X-Class solar flares are the most powerful. These bad boys launch massive loops - many times the size of Earth - off the surface and into the sun's magnetic fields. This process can create as much energy as 20 nuclear bombs.

So we're talking about incredibly powerful forces here. Forces so powerful, in fact, that an X-Class solar flare can trigger a coronal mass ejection (CME). CMEs are long-lasting radiation storms that interact with surrounding solar winds. A CME can eject as much as one billion tons of plasma from the sun's surface at speeds up to 1.6 million kilometres per hour.

This plasma - which is a cloud of superheated protons and electrons - can hitch a ride through space on a solar wind, and make the 150-million-kilometre journey to Earth in a few days.

While this sounds terrifying, CMEs are actually very common and rarely pose a threat to Earth. During active periods, CMEs occur several times a day. Even during inactive periods, a CME will usually show up once every five days.

And solar winds blow CMEs off the sun's surface in all directions. So the chances of a CME catching a solar wind pointed directly at Earth are relatively low. But that doesn't mean it has never happened. Or that it won't happen again.

At least a few significant CMEs have hit Earth. Scientists believe a solar storm impacted Earth about 9,200 years ago, and it was powerful enough to leave permanent scars on deeply buried ice in Greenland and Antarctica.

Much closer to modern times, a CME slammed into Earth's atmosphere in 1859. Known as the Carrington Event, it took out telegraph wires across the globe and ignited widespread fires. Some telegraph operators even reported receiving electric shocks from overloaded telegraph equipment.

In 1989, another CME caused a 12-hour electrical blackout across the entire province of Quebec in Canada. It also affected power grids throughout the US, caused short-wave radio interference, and sent several satellites tumbling out of control.

It all starts with the sun. That glowing ball of light in the sky is actually a 4.5 billion-year-old yellow dwarf star in the centre of our solar system. And it's huge and hot. The diameter of the sun is around 1.4 million kilometres, and its core heat tops 15 million °C.

The sun is also an incredibly active place. It is a ball of hydrogen and helium that's held together by its own gravity. Nuclear reactions at the sun's core create the heat and light we experience on Earth - about 150 million kilometres away.

Radiation carries this energy outward from the sun's core where it bounces around the radiative zone for 170,000 years or so. The energy eventually makes it outward to the convection zone, where the temperature drops to a chilly 2 million °C. This forms bubbles of hot plasma that move up onto the sun's surface.

This process can get pretty wild. Electromagnetic radiation eruptions in the sun's atmosphere - known as solar flares - can be incredibly powerful. Solar scientists classify solar flares according to their strength, much like the Richter scale is used to classify earthquakes.

X-Class solar flares are the most powerful. These bad boys launch massive loops - many times the size of Earth - off the surface and into the sun's magnetic fields. This process can create as much energy as 20 nuclear bombs.

So we're talking about incredibly powerful forces here. Forces so powerful, in fact, that an X-Class solar flare can trigger a coronal mass ejection (CME). CMEs are long-lasting radiation storms that interact with surrounding solar winds. A CME can eject as much as one billion tons of plasma from the sun's surface at speeds up to 1.6 million kilometres per hour.

This plasma - which is a cloud of superheated protons and electrons - can hitch a ride through space on a solar wind, and make the 150-million-kilometre journey to Earth in a few days.

While this sounds terrifying, CMEs are actually very common and rarely pose a threat to Earth. During active periods, CMEs occur several times a day. Even during inactive periods, a CME will usually show up once every five days.

And solar winds blow CMEs off the sun's surface in all directions. So the chances of a CME catching a solar wind pointed directly at Earth are relatively low. But that doesn't mean it has never happened. Or that it won't happen again.

At least a few significant CMEs have hit Earth. Scientists believe a solar storm impacted Earth about 9,200 years ago, and it was powerful enough to leave permanent scars on deeply buried ice in Greenland and Antarctica.

Much closer to modern times, a CME slammed into Earth's atmosphere in 1859. Known as the Carrington Event, it took out telegraph wires across the globe and ignited widespread fires. Some telegraph operators even reported receiving electric shocks from overloaded telegraph equipment.

In 1989, another CME caused a 12-hour electrical blackout across the entire province of Quebec in Canada. It also affected power grids throughout the US, caused short-wave radio interference, and sent several satellites tumbling out of control.

Read the full story:

About the Creator

Shane Peter Conroy

Shane is just another human. He writes, he paints, he reads. He once got his tongue stuck to the inside of a freezer. Actually, he did it twice because he thought the first time might have been a fluke. https://themalcontent.substack.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.