The remarkable power of Australian kelp

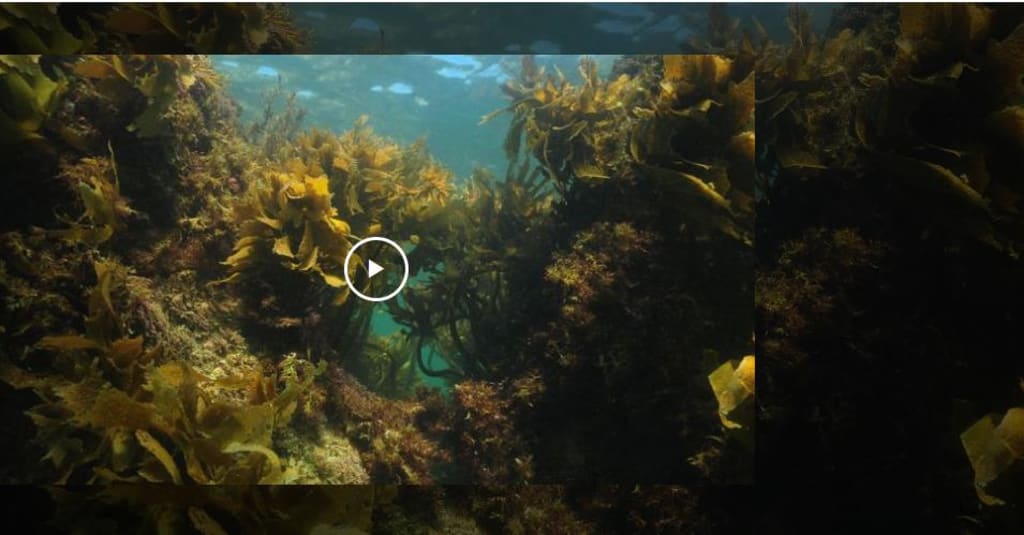

Algae is a powerhouse for the climate, sending carbon to the seafloor and deacidifying oceans. In Australia, scientists are just beginning to tap its potential.

re than 45,000 years ago, by the shore of present-day Tasmania, a local person picked up a large piece of thick, dark brown seaweed. Its impervious tissue and resilient flexibility sparked an idea, and they realised that this giant piece of seaweed could solve one of the day's nagging problems. The piece of kelp was fashioned into a small rubbery bag, its edges perforated with a stick to give it structure, and plant fibres twisted around the stick to make a handle. From then on, the kelp was used as a versatile water carrier.

The Aboriginal peoples of Australia were some of the first seaweed innovators in the world. And 45,000 years later on mainland Australia, people are again turning to algae to solve pressing problems. Today, it is not how to get water from A to B, but how to address the world's climate crisis. And in several large open-air bubbling green vats at an industrial complex in Nowra, New South Wales, Pia Winberg is exploring exactly how.

Winberg, a marine ecologist at the University of Wollongong, has spent decades studying seaweed. She believes seaweed's fast growth rate and ability to absorb vast amounts of carbon dioxide can help fight climate change, deacidify the oceans, and change the way we farm, not just in the oceans but also on land. In short, Winberg believes averting the worst of climate change will involve growing more seaweed – much more. (Find out more about the potential of seaweed in our video on BBC Reel)

Globally, seaweeds are thought to sequester nearly 200 million tonnes of CO2 every year – as much as New York State's annual emissions

"If we used the infrastructure we have in the ocean and created seaweed islands, we would actually eliminate a lot of the climate change issues we have today," says Winberg.

Realising seaweed's potential as a climate solution, Winberg opened Australia's first land-based, commercial seaweed farm in 2013. On her farm in New South Wales, Winberg produces seaweed extracts that are used in food, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals. If seaweed farming is scaled up, algae could replace plastic packaging and common animal feeds such as corn, according to Winberg.

"Seaweeds are a platform of opportunity, in sustainability, nutrition and innovation," she says.

The power of kelp

Despite its ancient history of making use of seaweed, cultivation of these algae is still in its infancy in Australia. The first cultivation of seaweed began in Japan in the 1670s and commercial farming took off in the 1950s. British marine scientist Kathleen Drew Baker's discoveries while studying the red algae porphyra led to a revolution in how an edible type of seaweed called nori was farmed in Japan. Today the seaweed is widely used in sushi, salads and soup.

Since then, seaweed farming has grown into a multi-billion dollar industry in Asia, with China producing over half of the continent's harvest each year. Now seaweed farming is starting to gain momentum in other parts of the world, in part due to growing awareness of the species' ability to combat climate change as well as its high nutritional value and fast growth. Besides its sustainability credentials, seaweed is cheap, easy to harvest and available worldwide, making it an attractive commercial proposition.

Forty-eight million sq km of the world's oceans are suitable for seaweed cultivation – an area about six times the size of Australia

Kelp is one of the most commonly farmed types of seaweed. The large, brown alga, which is found in cold, coastal marine waters around the world, grows remarkably quickly – up to 61cm (2ft) a day – and does not require fertiliser or weeding.

Like plants on land, seaweed uses photosynthesis to absorb CO2 and grow biomass. Coastal marine systems can absorb carbon at rates up to 50 times greater than forests on land, according to Emily Pidgeon, senior director of strategic marine initiatives at Conservation International. Globally, seaweeds are thought to sequester nearly 200 million tonnes of CO2 every year – as much as New York State's annual emissions. And when the algae dies, much of the carbon locked up in its tissues is transported to deep oceans.0

But these natural carbon sinks are also under threat from climate change. As carbon dioxide levels rise in the atmosphere, more of the gas is dissolved into the oceans, making it more acidic. Along with warmer oceans, this is already having a devastating impact on coral reefs and seaweed ecosystems.

In Tasmania alone, rising ocean temperatures and acidification have wiped out 95% of kelp seaweed forests over the past 80 years, destroying bountiful marine habitats and decimating fisheries. The warmer waters provide perfect breeding conditions for sea urchins, which have devoured the underwater forests.

"It can be quite catastrophic, like in the case of disappearing kelp forests. It's so dramatic. It's like going from a rainforest to Moonbase Alpha," says Winberg.

As well as taking carbon out of the atmosphere, seaweeds also help rehabilitate their immediate environment by lowering the acidity levels around them, according to a 2018 study by ecologists Nyssa Silbiger and Cascade Sorte at the University of California, Irvine. "If you have more seaweeds taking up more carbon dioxide than what is produced, you actually offset acidification and return [the ecosystem] to the state life can persist in," says Winberg.

By raising pH levels in the ocean, seaweeds also improve growing conditions for shellfish such as oysters and mussels, whose shells become more brittle in acidic environments, explains Halley Froelich, a marine scientist at the University of Santa Barbara. "If you throw seaweed next to oysters, it creates somewhat of a halo effect," says Froelich. "It can provide a localised buffer."

Froelich is the lead author of a study that found farming seaweed in just 3.8% of federal waters off the Californian coast could offset all the carbon emissions from the state's $50bn (£36bn) agriculture industry. The study concluded that 48 million sq km (18.5 million sq miles) of the world's oceans are suitable for seaweed cultivation – an area about six times the size of Australia. "It is an untapped potential," Froelich says.

Farming seaweed

The potential for seaweed cultivation doesn't stop in the oceans. Winberg has found there are benefits to doing it on land too.

Winberg's farm in Shoalhaven, New South Wales, uses carbon emissions generated at a wheat refinery next door to grow large quantities of seaweed biomass. The CO2, which is released during the fermentation process at the refinery, is mixed in bubbling green vats with seawater, and algae pumped in from the local river.

CO2, nitrogen and other nutrients from the nearby refinery fertilise the algae to produce large amounts of green seaweed which is dried and used as extracts in a wide range of products including toothpaste, paint and ice cream.

Winberg believes that seaweed farming offers "huge potential" to not only address the climate crisis, but also feed a growing population in a sustainable way. The World Bank estimates that if the sector is able to increase its harvest by 14% per year by 2050, seaweed cultivation could increase the world's food supply by 10%.

"There are inherent limitations to traditional farming. It is the number one driver of biodiversity loss," says Froelich. "There is great potential for seaweed farming to supplant some of that pressure at a lower cost."

According to Winberg, one hectare of a seaweed farm can produce more protein than the same amount of land used for cattle. "We're sitting on undiscovered, renewable, sustainable resources," she says.

Seaweed could also help make cattle farming more sustainable. Research from the University of California, Davis, found that feeding seaweed to cows significantly reduced the amount of methane from their burps and farts. Methane is a highly potent greenhouse gas which, although shorter-lived in the atmosphere, has a global warming impact 84 times higher than CO2 over a 20-year period.

Adding a small amount of red seaweed called Asparagopsis taxiformis to their diet dramatically reduced cows' methane output. "We saw a reduction of over 80% or more when adding just one or two ounces of seaweed. That was a big surprise to us," says lead author Ermias Kebreab. The reason is that compounds in the seaweed inhibit the enzymes in cows' stomachs that produce methane. "Reducing methane could help us in the short-term reverse some of the climate effects. It gives us a chance to slow down global warming." Researchers are now investigating whether the meat and milk from cows who have eaten this seaweed is safe for human consumption, after research found that the animals may accumulate toxins from their seaweed-enhanced diet.

In the tens of thousands of years of human experimentation with seaweed, the scale of the challenges that humble seaweed can help to solve has grown immeasurably. But some things are still the same. To the Aboriginal Australians living in Tasmania who first discovered some of seaweed's uses, it might have seemed like a wonder material as they fashioned watertight bags out of kelp. To seaweed experts like Winberg today, this old idea is still ringing true.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.