Sunstorms Unleashed: Could They Wipe Out the Web?

Exploring the Terrifying Threat of Solar Storms on Global Internet Infrastructure.

In August of 1859 astronomers around the world watched with Fascination as the number of sunspots began to grow on the surface of the Sun. Among those astronomers was Richard Carrington an amateur skywatcher in a small town called Red Hill near London in England.

On September 1st, Carrington was sketching sunspots when suddenly he was blinded by a sudden flash of light so bright, he thought a hole had formed in his observation screen and that he was directly observing the sun. After adjusting his equipment and finding to his surprise the intense white patches remained he ran out of his Studio to find a secondary Observer, but when he

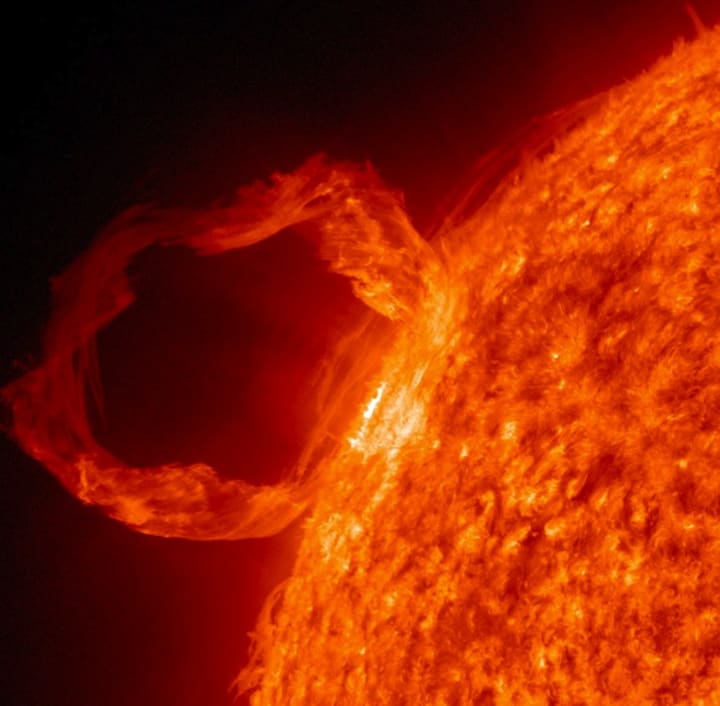

returned, the bright spots had already faded. What he didn't know at the time was that the explosive energy he had just witnessed on the surface of the Sun was now rushing towards him and everyone else on Earth. What Carrington had seen was a major coronal mass ejection - a burst of magnetized plasma from the sun's upper atmosphere.

These corona ejections usually take multiple days to reach Earth but just 17 and a half hours later, the ejected plasma had traversed over 90 million miles (150 million kilometres) and began to unleash an unprecedented geomagnetic storm.

Auroras otherwise known as the northern lights were seen as far south as the Caribbean. The Aurora over the Rocky Mountains in the United States was so bright that the glow woke up gold miners who began preparing breakfast because they thought it was morning! Spontaneous fires were reported in several major cities. Electrical systems all over Europe and North America began to fail and Telegraph pylons threw Sparks, and in some cases electrocuted their operators. Some telegraph operators even found that despite power being switched off they were still able to send and receive messages as their machines were being powered solely by the overhead aurora. This geomagnetic storm was the worst in modern history and it became known as, the Carrington event.

The energy ejected from the Sun was estimated to be equivalent to 10 billion megatons of exploding TNT! Imagine the infamous Tsar bomb, the most powerful thermonuclear weapon ever detonated and you're about five billionths of the way there!

It's been conjectured that if a storm happened on the scale of the Carrington event today, it could cause an internet apocalypse inducing extreme voltages in our electrical wiring threatening the stability of the electrical grid - even the possibility of destroying undersea cables that carry much of the world's internet traffic. Recently the internet has been buzzing with the fear that this event May reoccur in the next 18 months as we enter a peak period of sun activity in 2025.

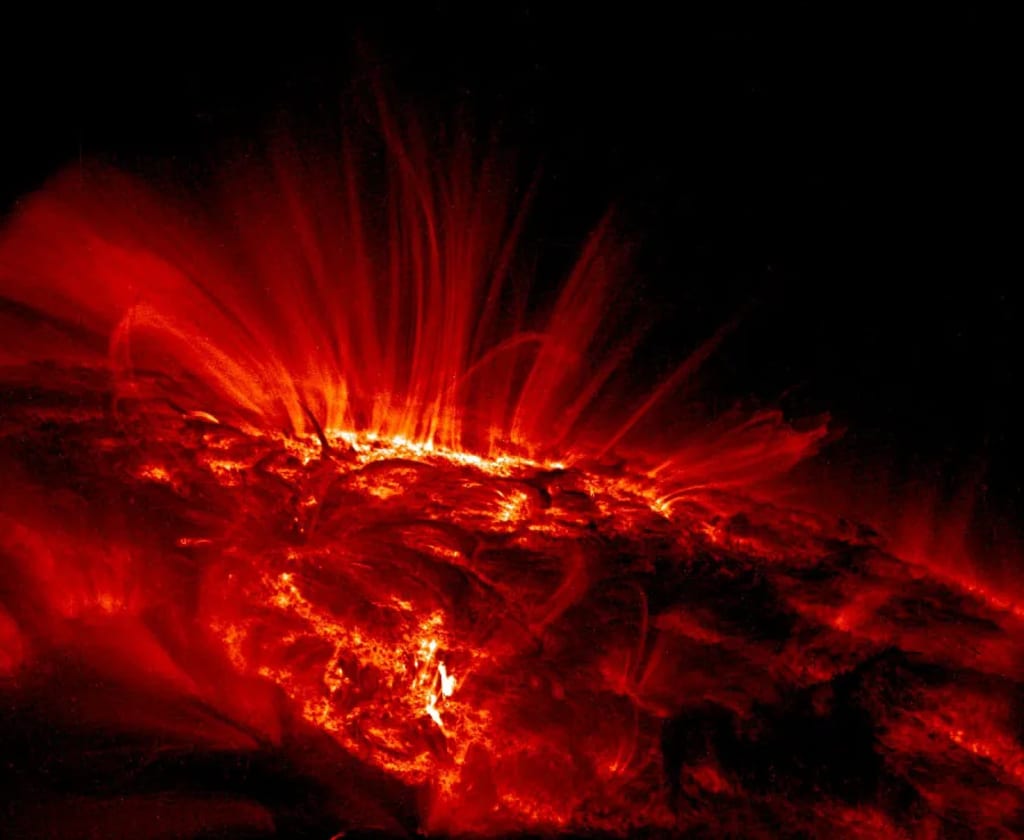

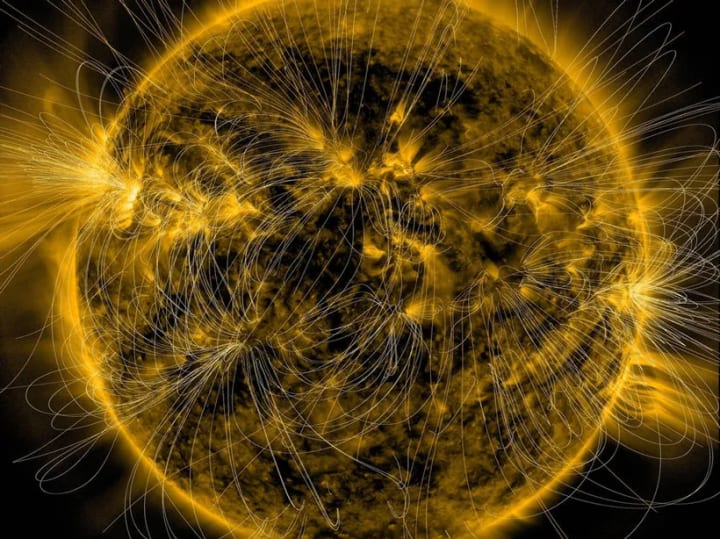

Every 11 years or so the sun's magnetic field completely reverses and these cycles can be as short as eight years or as long as 14 and vary dramatically in intensity. As the magnetic field lines change, so does the amount of activity on the sun's surface including things like solar flares, sunspots and coronal mass ejections. These explosive coronal mass ejections generally begin when highly twisted magnetic field structures otherwise known as “flux ropes” that become so stressed they realign spontaneously into a less tense configuration, a process called “magnetic reconnection”. This can result in the sudden release of electromagnetic energy in the form of things like solar flares which are typically accompanied by the explosive acceleration of plasma away from the Sun - the coronal mass ejection. They usually take place from areas of the sun with localized fields of strong magnetic flux coming from regions associated with sunspots and located along the mid latitudes approximately 30 degrees north and 30 degrees south and the largest coronal mass ejections can contain billions of tons of solar material and burst out from the Sun at up to 3,000 kilometres per second.

They expand in size as they propagate away from the sun and the largest coronal mass ejections can reach a size comprising nearly a quarter of the space between Earth and the Sun. If they do strike Earth they play Havoc with Earth's magnetic field. But could they really Wipe Out the internet?

To answer that question we have to understand a little bit deeper as to what's happening. A solar storm provides a large-scale demonstration of something called Faraday's law - the idea that varying a magnetic field will cause a change in the local electric field. As the charged plasma of the solar storm approaches the Earth, Earth's magnetic field is distorted and weakened. Most electrical systems are connected or grounded to the Earth in some way, so when the geoelectric field of the Earth changes this can enter electrical systems through those grounding points creating large voltages short-circuiting or even destroying entirely those Electronics.

Most large electrical infrastructure systems have ways of dealing with these sorts of events when they are of normal magnitudes but failures still happen. On March 13 1989 a solar storm caused the entire province of Quebec Canada to suffer a nine hour long electrical power blackout as the storm overwhelmed Hydro Quebec's electricity transmission system.

The infrastructure however that is most difficult to repair would be the undersea cables that connect most of our internet across the world. Typically these cables are Optical fibers, carrying information as light, and as a result, are made out of glass not copper so solar storms in theory shouldn't affect them. However these undersea cables also contain a copper electrical line to power the periodically placed repeaters that boost the power of those light signals making these electronic systems vulnerable.

We can find signatures of large past solar flares and coronal mass ejections in carbon 14 tree rings and looking at beryllium 10 ice cores. The signature from a large solar storm was found about a thousand years ago that was estimated to be about 20 times the usual activity of the Sun or about 10 times the size of the Carrington event. Well beyond the limit of any deep sea cable to withstand!

Estimates vary from once per 100 years for a Carrington level event, to once per Millennia for

ones that are much more powerful and unfortunately we're overdue for both. However solar cycle 25 looks very much like the last four solar Cycles before it - reasonably tame in the grand scheme of

Solar activity. If I was a betting man I'd say probably not something to lose sleep over - for this solar cycle at least.

But then again the past decade has had a good handful of once in a lifetime events, so what's one more.

About the Creator

Chris Wilson

Driven by progress, I navigate complex landscapes with an agile mindset. Challenges fuel my growth. As a visionary, I shape a brighter future through innovative impact. Join me on this inspiring journey of limitless exploration.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.