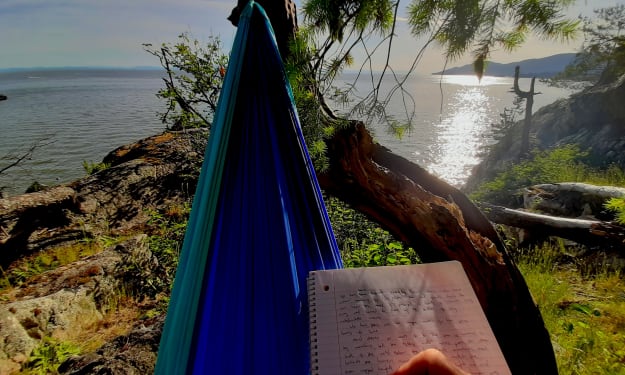

Lose Your Self. Find the World.

Nature can save you from a life without meaning.

It happens every year

Calendars turn. Leaves crumble and rust. Summer’s silent hallways fill with footsteps and laughter. The clocks miss a stuttering step.

Some great mystery calls the salmon home. They hear it in the cold dark depths of the ocean and follow it in blooming swarms, heading back inland into the cage that waits for them. The trackless sea becomes a muddy estuary, a river winding between autumn’s gilded mountains, or a lake in a shallow stony bowl.

As they swim upriver, the salmon seem to mutate. They sprout exaggerated jaws and teeth. Some of them turn the bright red of a drop of blood welling up from pricked skin, glowing with the life it contains.

The change from saltwater to freshwater kills them. By the time they reach the rivers where they were born, their bodies are already beginning to rot. It’s an armada of zombies.

But none of that matters. All that matters is that they lay their eggs in a scooped-out hollow under the water so that more salmon will swim through these rivers in years to come.

Everything depends on this.

Bears wait by spawning streams, tacking on those last few pounds of fat before lumbering off to sleep away the winter. Wolves slink down from the mountains, following their noses to the stink of rotting fish. The trees in these forests grow so tall in part because of the life-giving nitrogen they absorb from fish carcasses dragged into the woods.

And another army is heading this way. Except this time, it’s an air force. Bald eagles drift down from Alaska in the thousands, dark bodies and bright yellow claws dangling from the sky between broad wings flung wide to embrace the sun. This Canadian valley hosts one of the world’s largest gatherings of bald eagles. One by one, they drop out of the sky like a curse to feast on a river bloated with death that winds beneath them.

Upriver, a steamship rots underwater. Once, it carried prospectors and miners and pack mules into the province’s wild interior in search of gold. Gold still washes down from the mountains now. Tiny flakes shimmer and shine as paddlers kick up sand at the beach. It’s no longer worth harvesting such small rewards.

But for the eagles, the river turns up the same treasure at the same time every year. When I arrived at the lake, I saw four of them, sitting with hunched shoulders in two slender trees rising from a sandbar island.

Waiting.

Eagles know how to be patient, but humans need something to aim for.

We are interested in straight lines more than we are in cycles. Even though we can see that everything moves in a circular pattern, the whole symphony repeating itself again. Eagles can live a long time, and some of these birds were surely here last year and the year before and maybe even ten years ago when I first came to this place.

But every one of the fish they’re waiting for is different. For the salmon, this is a suicide mission that brings life out of their death for the deathless forest. In Indigenous art, the salmon has a head that splits in two to reveal the smiling god inside. For the first people to discover these forests and mountains and lakes, the source of all life was not in the heavens but in the watery depths below.

They were right about that.

We don’t see it that way anymore. We prefer straight lines, like the railway tracks that slouch across the water. We have to aim for something, the twin lines of the railway slowly converging and yet never quite reaching one another. Always disappearing into the undifferentiated horizon just as they reach out to touch.

None of us are immune. We all wonder where this is going. What the point of it all is. As though there needs to be some satisfying dénouement, a perfect third act that refers back to the first and settles the conflict established in the very beginning.

Addicted to story as we are, we’ve confused art for real life. The world doesn’t work that way. The only stories are the endless patterns of nature, and they go on and on without ever asking why.

We can’t look into the mind of an animal

We don’t know if birds are happy. We don’t know if they capable of that. The closer an animal is to us in Linnaeus’ branching shrubbery, the more confident we feel intuiting its motives.

Apes and elephants clearly feel things very deeply. Every pet owner knows the same is true for dogs and cats. Birds are further from us, coming as they do from the dinosaurs that still fascinate children with the strange intensity of those who secretly want to be devoured.

Eagles don’t make faces. Their intense golden stare is ultimately unreadable.

But there is a kind of joy that comes from doing the thing you’re made to do. Horses run, whether we make them or not. Dogs can’t resist a chase. And we like to eat and sit around the fire and sing songs together.

We like to feel part of something, the way our ancestors needed to be to survive. It’s humbling to consider how much of what you like is dictated by your genes, your species, the body you inherited from millions of years of evolution. Sure, we are all individuals. But even to the keen eyes of eagles, all humans seem more or less the same.

It’s not hard to imagine the joy of flight. From the mountains rising behind the lake, paragliders ride the same thermals the raptors do. If eagles ever feel anything like joy, it must be at the feeling of the wind in their feathers, the sudden turn and dive, the cold plunge of cruel talons into the water to haul out a wriggling catch.

Few things inspire wonder like nature

The works of human genius can provoke the same sense of awe in a different way. The ceiling of the Sistine Chapel lets us admire the capacity of a single individual to re-create an entire world. But in nature, there are no individuals. Every salmon feels as though it’s acting out of pure self-interest. We are far enough away to see that isn’t true. Following their urges and pleasures have brought them here to die on these beaches and be torn apart by black-cloaked monsters from above.

The salmon didn’t create this world any more than we did. And they are no more selfless than we are. In the cold depths of every slow fishy heart, the salmon are chasing their own goals as assiduously as we do.

And in the sky above, God and man reach out languidly toward each other, cloaked in glory and about to touch. Except they never quite do, do they? The story that’s worth telling is in the reaching, not the touch.

None of this matters

You have a life to live, and it’s far more complex and interesting than that of a fish. Every year, I come to see the eagles with a camera lens that was assembled according to principles of physics that I don’t understand. Built by strangers on the other side of the world so that I could record an annual event that’s been going on for millions of years. Yes, our lives are complex. But complexity is not the same as meaning.

For weeks, the salmon will keep climbing the long ladder of water that leads them back to where their lives began. For weeks, hordes of eagles will climb rays of sunlight into the sky, dropping like a curse at the telltale flash of silver breaching the surface of the lake.

But we will turn our backs on the sun, and the salmon will stop running, and the water will freeze. The eagles will stick around for a while, building nests and laying eggs and raising young that will spread clumsy wings to the sun by the time spring returns.

You can go your whole life and never see a natural phenomenon like this.

Many people do. After all, it doesn’t put money in your bank account or food on your table. What gets lost when we willfully isolate ourselves from the profound patterns of the world of which we are inextricably a part is fragile but precious. And just because it’s hard to put a name to doesn’t mean it’s not real.

There’s a humility that comes with seeing the infinitely complex workings of the world. A breathless rapture that lifts you out of yourself, toward the high mountain crags that the eagles drop from on their way to the lake.

It’s not a question of seeing yourself as something small and insignificant, the way people say they do when they look at the stars. It’s more about seeing the intricate patterns that you are a part of. It’s an encounter not only with nature, but with your own true nature, the real existence that the job and the phone and the five-year plans are robbing you of.

And if you never get that sense of awe for yourself, that unique feeling of your self vanishing into the background as something unknowable does something unimaginable all around you, you’ll live your whole life in a glassy prison. You’ll waste both time and energy on things that don’t matter, chasing those steel rails forever into the distance.

A futile quest to find the impossible place where they finally meet.

About the Creator

Ryan Frawley

Towers, Temples, Palaces: Essays From Europe out now!

Novelist, entomologist and cat owner. Ryan Frawley is the author of many articles and stories and one novel, Scar, available from online bookstores everywhere.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.