In June of 1974, the Chilean National Football team or “la Roja” gathered for a speech presented by their head of state, Augusto Pinochet, before being sent abroad to the World Cup. Only nine months earlier, Pinochet had assumed the position as president of Chile after a successful coup d’etat which resulted in the death of former Socialist President Salvador Allende and the so called “interior war” propagated by Pinochet’s regime against civilians. This speech came days before the team was set to travel abroad to play in the World Cup tournament against West Germany. At the conclusion of the speech, the team members stood in a line as Pinochet and five government officials shook their hands. One member, Leonardo Véliz remembers this experience and stated that, “having to shake hands with the head of a government that practiced state terrorism was very difficult.” Another teammate, Carlos Caszely recalled the same moment, sharing a similar opinion as Véliz. However, Caszely did not submit himself to shaking hands and in that moment refused to do so. “A cold shiver went down my spine” he recalls, “when he started coming closer I put my hand behind me and didn’t give it to him.” According to an interview with the player, Caszely states that his refusal to shake hands with Pinochet came after news of his mother’s abduction and torture by the Chilean police. In retrospect, he believes the initial abduction to be a sort of warning for him to keep his silence about the state of the country while abroad. Caszely’s decision to not acknowledge Pinochet is widely regarded as the first public display of dissidence against the regime since it’s beginning.

This act is significant when analyzing the relationship between Chilean football and politics in the early Pinochet years because it reveals the privileged status of football players under the dictatorship. According to reports, between September 11 and November 15, 1973 the Chilean army had detained between 7,000 and 8,000 citizens. Most of those arrested were persecuted for speaking out against Pinochet, for being activists, students, or for being alone on the street. Even public figures were personally target by the regime including folk musician Victor Jara and poet Pablo Neruda. Given that the regime was willing to target anyone no matter their profile in society goes to support that football players were privy to immunization from the regime based on their role and importance as football players.

1974 Chilean National Team (bottom left: Carlos Caszely) (source: worldsoccer.com)

Another aspect that should be taken into consideration is the Chilean army’s use of the Estadio Nacional de Santiago as an imprisonment camp. In the context of this paper, the stadium acts as the primary site of interaction between football and politics. The government’s use of the area which was previously associated with enjoyment, entertainment, and cultural tradition was transformed into a hostile arena for thousands of Chileans. Both of these examples lend themselves to prove that football was so engrained in Chilean society that it could be manipulated as a vehicle for political agenda.

Background

To understand how Chile got to the point where the government was detaining citizens inside its national stadium requires some historical background. Augusto Pinochet’s rise to power came following the death and deposition of former Chilean president Salvador Allende. Allende had run in a previous election to Eduardo Frei before narrowly winning his own but was controversial from his first day in office because of his socialist ideas. He was supported most by lower and working class peoples as well as some portion of the middle class but was intensely despised by both the upper class as well as the United States. This was largely due to his socialist policy reforms, the most significant being his proposition to nationalize Chilean industries like mining from which the wealthier class and the United States profited. President Nixon said of Allende that “he’s a real son of a bitch” and at one point stated that he wanted to “make the Chilean economy scream.”

Nixon followed through on this intent and organized one of the biggest union protests in Chilean history via the truck drivers. Being a country longer than it is wide, Chile depended on these truck drivers to deliver goods from one end to the other. This set off a catalyst of events, eventually culminating in the coup d’etat of 1973. On September 11, General Augusto Pinochet led members of the Chilean army in the coup, storming the presidential palace at LaMoneda and reportedly leaving Allende no other choice but to shoot himself with a gun given to him by Fidel Castro. From this day until 1990, Augusto Pinochet held the title of head of state exercising what bared no resemblance to a democratically attained position of power.

Carlos Caszely

One of those players who supported Allende from the beginning and made clear his political views was Carlos Humberto Caszely. Born in 1950, Caszely has been regarded as one of the best Chilean football players of his era and has since been given the nickname “king of the square meter.” Before his foray with the National Team Caszely played for another distinguished Chilean team known as Colo-Colo where he set the record for top scorer with 208 goals. He also spent time studying but claims that he faced adversity for it because people do not think of football players as needing to be smart, only to be good at the game. He states that people did not like football players to talk politics, that they wanted the sport to remain as apolitical as possible.

Caszely’s voice in politics was one that echoed the sentiments of Salvador Allende. He had been an open supporter of Allende’s party, the Unidad Popular since the 1960s and at one point had endorsed Gladys Marín, communist supporter and later leader of the communist party in Chile. Marín said of Caszely that “he was not only a great sportsman, but also a young man who understands the revolutionary process his country is experiencing.” Upon the end of Allende’s reign Caszely became afraid of life in Chile. He recalled that there was nobody on the streets and that fear was not just isolated to one part of society but that it was everywhere. To cause such an immense amount of fear in the general public that nobody dared walk in the streets of Santiago goes to show the lack of discrimination Pinochet used against civilians and especially those with dissenting voices.

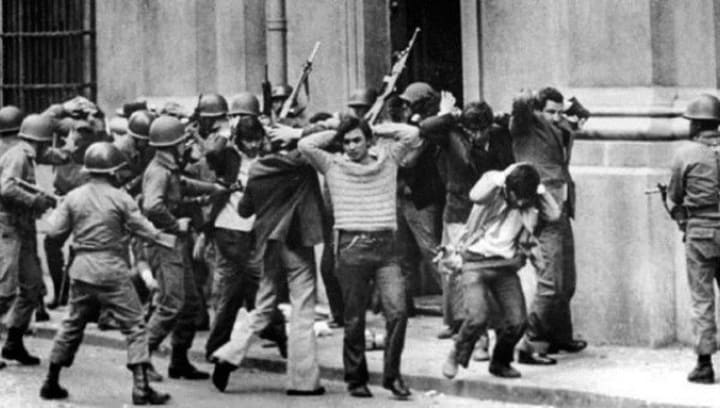

Coup d'Etat Santiago, Chile 1973 (source: telesurtv.net)

Given that the dictator was most likely aware of Caszely’s political opinion it seems out of character that he did not persecute the football star. However, evidence shows that Pinochet regarded the national team highly. Originally, the dictator did not want the team to go abroad until further deliberation between him and his colleagues convinced him that the team was an important symbol of prestige for Chile and that they needed to play in the World Cup. There is also evidence that Pinochet was aware of Caszely’s opinion because of the abduction and torture against his mother only days before the team’s travel to Germany. “Its not easy to express what its like when your mother undoes her blouse to show you where cigarettes had been put on her flesh…” said Caszely in an interview. Though incredibly personal, the torture of Caszely’s mother was as close as the dictator got to him. The football player remained in Chile during the coup and for the duration of Pinochet’s regime, meaning he was entirely reachable by the army yet was never touched. This further suggests that Caszely’s role as a famous football player was more important to the dictator than was persecuting him. Both Pinochet’s decision to allow the team to go abroad and his restraint from persecuting Caszely is indicative of the importance of football to Chilean society and politics during the years 1973 and 1974.

National Stadium of Chile

Another indication of the importance of football as a cultural past time was Pinochet’s use of the Estadio Nacional de Santiago as an imprisonment camp. From September 11 to early November 1973 the Chilean army detained and tortured around 6,500 people including non-Chilean citizens. Telegrams from the Chilean embassy to the United States embassy in September note that there was no such record or evidence of any persons being held or any evidence of mass executions. This information contradicts a statement made by the head of the Chilean Football Federation, Francisco Fluxa, who stated, “I knew they were torturing people. Of course it bothered me. But the whole world knew that political prisoners were being held there.”

Accounts from citizens detained in the stadium are abundant and easily accessible. Many recalled feeling cold, tired, hungry, and uncertain about the future. Parts of the stadium itself became associated with fear including “the black disk.” Over the loud speakers, one man recalled that they would call for certain individuals to come forward and line up at the "black disk" for interrogation. They sometimes were also brought to the velodromo which came to be associated with torture by those living inside the stadium.

When the Fédération Internationale de Footbal Association (FIFA) got word of the rumored atrocities they sent officials in to investigate. “We went straight to the center of the field. It must have lasted 10 minutes. No more” Francisco Fluxa recalls. According to victim testimonies, the FIFA officials were investigating while they were being held hostage underground with guns to their heads. After the initial search, the officials gave Chile the green light to host their football match against the Soviet Union on November 21, 1973. Though the Soviets declined to play in a stadium because of the alleged atrocities, many of the prisoners were reported to have been released by this point. Caszely recalls the “show” they put on when they played their match against no opponent saying, “that was when we became a part of the farce.”

Estadio Nacional de Chile (source: stadiumguide.com)

The National Stadium was then transformed from a site of national pride where the Chileans had hosted the world cup only 11 years earlier, to a place where a dictatorial regime was detaining, torturing, and killing its own people. Some scholars argue that Pinochet’s decision to host the majority of detainees here was a purposeful act intended to scar the positive memories of the nation and in turn replace them with memories of pain and loss. Pinochet incited fear into his people and used this tool to his advantage. The use of the National Stadium as a torturing ground was strategic in that it manipulated an emblem of culture and pride into a symbol of fear. By torturing people with electricity, water, and beatings in the national stadium he created a new significance to the site. He was likely aware of how the Chilean people might associate the National Stadium with a national identity. Since nationalist rhetoric can be damaging to an oppressive regime, the most tactical move Pinochet was to make was to use the stadium as a vehicle for torture. Again, the reverence of football by the Chilean people was so prevalent during this time that Pinochet used it against his citizens. By taking a collective memory of something inherently positive to Chileans like football and molding it into an oppressive symbol was a way that Pinochet enacted his political agenda of dictatorship.

Chilean army officials guard imprisoned peoples in Chile's National Stadium (source: cronicadigital.cl)

Both Carlos Caszely and the National Stadium are examples of how football and politics in Chile were intertwined with one another. They both stress the same point but in seemingly opposite ways. Pinochet’s immunization of Caszely from persecution was reflective of a political agenda that he wished to push. By making Caszely a victim of the regime he would have in turn made him a martyr for the people and thus been a catalyst for an uprising. However, in that case, Pinochet was using football to his advantage in that he allowed the Chilean citizens to relish in Caszely as a symbol of pride for the country yet did the exact opposite when it came to the stadium. With the use of the stadium as a torture facility, he was taking something away from Chileans, that being a collective national memory. Whereas both Caszely and the stadium represented the pride of Chile and Chilean football, one was used to unite a people and one was used to suppress them. Still, both were tools used strategically by Pinochet to manipulate and control a mass of people and both reflect the importance of football in Chile as a vehicle for political agenda.

About the Creator

Kristen F

My death row meal would be an iced coffee with double cream and a warm croissant.

instagram: @kristen_foland

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.