Content warning: The following depicts scenes of violence that might be disturbing to some readers. Reader discretion is advised.

I don’t mean to speak ill of the dead. Mama would have my hide for sure. That said, if I’m to tell this story, I need to be free to tell it in my own words and my own way. I need to be able to speak on what I rightly recollect. That’s what I aim to do here.

Master Thomas was a mess! Now, to be truthful here, I need to say, my very earliest memories of him are probably not memories at all, but more my impression of things I heard grown folk talking about around me. And they all said he was a mess!

His daddy, Master James, bought that fool boy a plantation of his own! A small one, mind. And he somehow wrangled a marriage between him and the oldest Chaigneau girl, Therese.

The Chaigneaus, like the LeClairs, were a French Hugonaut family. They were very wealthy and powerful. Therese’s father, Francois, was a prominent lawyer and later, judge. And Master James was a decorated military General and owner of one of the largest plantations around. It seemed natural to them to join the two families, I suppose.

Master Thomas was a sickly sort. He was frail and bone white from the very first time I set eyes on him. He often was laid up in bed with some sort of ailment or another. Seemed to be a breathing problem, if I recall correctly, but I can’t swear to that.

In any case, he had no ability or aim to run a plantation, so we were shipped off to him with a bundle of other slaves to get the place in working order.

Our quarters were small. I can’t say how small, but much smaller than they’d been at Master James’. It always felt cold and damp. And there never seemed to be enough to eat. My little belly always felt empty, but it got fat and round just the same. The white folks liked that, they said I was fat and shiny. I don’t know about all that. All I know is that I was hungry.

At the first of the week, we’d get our allotment and it had to last the entire 7 days. Sometimes it was 3 or 4 quarts of corn or peas, maybe beans. Other times it was a peck of yams or potatoes. It was like they were trying to feed four of us on what could barely feed one.

Every once in a great while, Miss Therese gave Mama a couple of pigs’ feet. White folk don’t eat no pig’s feet. Of course, it still always looked like someone gnawed all the meat off before they gave them to her.

Mama and Daddy worked in the fields. That was hard on Mama. By that time, she’d birthed 3 babies, the youngest being my sister, Laura, who was still suckling. She just strapped her to her chest in some cloth and went about it.

A girl by the name of Bunny watched over me and my other sister Harriot and some others. She was pudgy, with dark eyes and a mild way about her. Her mama was working in the Big House for Master Thomas and Miss Therese. Bunny was sophisticated somehow, like she knew things we could never know even though she was only 8. She was like a grown woman but in a child’s form.

One day, about a week after I turned 5, Mama told me I was going to come to work with her from now on. I was excited. I used to watch the men and women go out to the fields and feel envious. I wanted to go too. I wanted to be useful.

Being useful was good. Being useful meant you didn’t get whipped. Master Thomas wasn’t all that keen to whip, but his wife sure was. She’d have a body whipped for the slightest offence. You look at that woman sideways, she’d have you whipped, and she’d stand there watching, with a smile on her face. And she wasn’t shy to whack you herself with whatever she had on hand if she had a mind to. A pot, a pan, a stick. She’d beat you about the head and then send you to be whipped. Mean as a snake, she was!

The first whipping I saw was on that plantation. I was almost 6, might have turned 6 already, I can’t say for sure. I was with Mama. My job was bringing water back and forth to the fields. In between, I tended livestock and the gardens. It was important work and I felt mighty important doing it.

There was a big Negro, Moses. He was what they call the overseer. He walked around, in charge, making sure everyone was doing what needed doing. He was nearly as wide as he was tall and sometimes, he’d just stand there, watching everyone work till they were almost ready to drop, holding that whip. And boy, didn’t he look proud!

He loved that whip the way a cowboy loves his horse. He walked back and forth, his stride long and purposeful, his eyes menacing. He was eager to catch his fellow Negro doing wrong. He took pleasure in it. It was almost as if he thought that whip in his hand made him a white man.

I remember the day being especially hot. And a man was looking mighty wobbly. It was planting time and his row wasn’t perfectly straight. Moses ran out and ordered him to straighten it up. He tried, but it wasn’t to Moses’ liking.

The man was Abraham. He was almost 50 and had served Master Thomas’ father, Master James, faithfully for years. He was an expert in ditch digging. But he was old and worn out. The sun was beating on him, and he needed water.

It was my job to bring water. But I was told I could only bring it every so often. And only on Moses’ say so. If I went against that, I’d be whipped. I wanted to. Maybe I should have. But as a boy, I didn’t. I was scared. I was told from the day I was born that my place was to shut my mouth and do what’s asked. That’s what I did.

So, his row remained askew. Miss Therese was on the veranda, I remember that. She was fanning herself and looking smug. No, she was looking more than smug, she looked excited, almost joyful at the prospect of seeing the whipping she knew was coming.

Moses looked back at her, I swear he did, smiling and showing his missing front tooth. Proud as a peacock. He ordered him to strip off all his clothes.

Abraham begged, “Please, “I’ll do better, please have mercy.” It did no good and soon his clothes were on the ground. Moses stood towering over his naked body and ordered him to cross his hands in front of him.

Abraham begged again, but his pleas fell on deaf ears. Moses leaned over the poor man and laid into whipping! He screamed at him, calling him all sorts of names and ordering him to get up as he wiled the lash with a sick ferocious delight, over and over.

And he did it all right in front of us.

Normally, slaves were taken away to the shack for whipping, but Moses wanted to put the fear in us all. He wanted to make an example of the poor old man so that we’d all work harder.

Nobody dared come to his aid. I remember standing there, same as the rest, slack-jawed and terrified. To see a grown man like that, on the ground, helpless. It’s burned into my mind to this day.

I stared as he lashed and lashed 3, 4, 5, 6 times, leaving marks and breaking the skin on Abraham’s back clean open! I saw the blood ooze out. I also saw the fury with which Moses flogged him. Each lash was stronger than the last. He seemed to take pleasure in it.

Why?

The brutality wasn’t lost on me, even then. And when it was over, Abraham lay in the field, shivering from pain, but too scared and weak to cry out. He shook silently as Moses strutted away, big as life, toward the Big House. He ordered two men to haul him back to the shack and wash him with brine. That was supposed to keep the wounds from festering. Once he was washed up, ol’ Abraham was ordered back to work.

I recall hating Moses then. And I told Mama and Daddy so. Mama knocked me half senseless and told me I was never, ever to hold hate in my heart. Daddy told me I best shut my mouth and forget what I saw. If a man can’t keep up, that’s what’s liable to happen. He said that was just a fact of life that I’d best get used to because there was no changing it.

Thing was, I could grasp the white man whipping us. But how could another Negro, another slave, inflict that kind of thing on us? A man subject to bondage himself. Why didn’t he rise up, with his size and strength, and say no?

Mama told me that people who have no power will grab onto any little bit they can get. She said it was for that reason I needed to find forgiveness in my heart for Moses. He was given a little bit of power as an overseer and he cared for that feeling more than he did the rest of us, but only just.

She said he had no choice in the matter. He either done the whipping or he would get whipped himself. When it comes down to it, I suppose a man will look out after his own hide first, right or wrong.

I forgive him now, not for him. But I do for me. As an adult, I can understand. I don’t condone it. I don’t think he was right. But I can’t sit here and tell you I’d have done any different given the circumstances. I’d like to think I would. I can’t say for sure.

Truth is, I got no right to judge. I didn't do different. In fact, I did the same thing. I did what I knew, even as a boy, was wrong. I didn’t bring water to a man dying of heat and thirst. And I did it to save my own skin. Doesn’t make me no better than Moses, does it?

Master Thomas died on a Wednesday in 1772. He wasn’t but 26 years old. Everyone acted so surprised. We weren’t. He was nigh on death more than he was living. Didn’t even draw up papers. You’d have thought someone so close to death all the time and with all that money would get papers made out just in case.

But that was ‘bout the best thing for me because we went back to Master James. What they did was pretty much join both plantations together. Now, they weren’t physically together, but they put them under the same umbrella and ran them both under Master James’ purview.

......................................

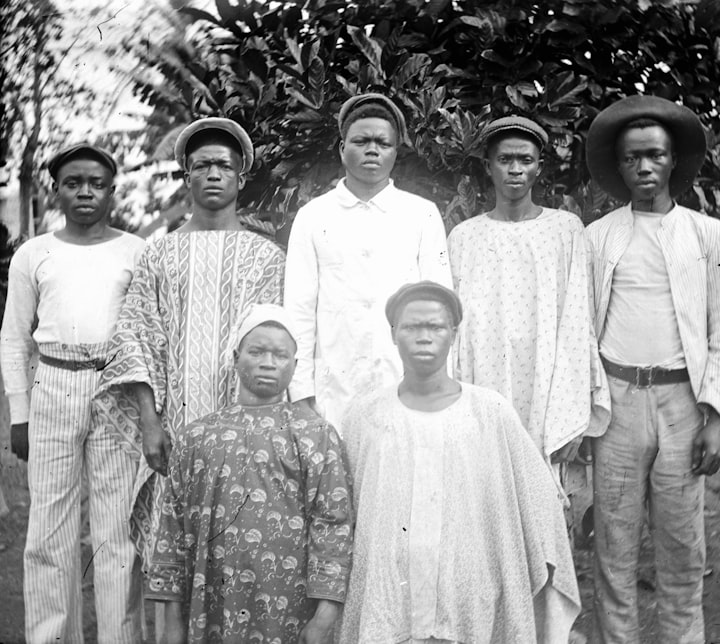

This is the second chapter in my upcoming novel, I Ran So You Could Fly which is a fictional account of my real-life 6th great-grandfather, Paris O'Ree. Paris was held as a slave on a rice plantation, along with his parents and sisters, owned by Col. Elias Horry in or around Santee, SC.

At 15, he ran away to join the British army in the Revolutionary War. As a result of his service, he gained his freedom and passage to Canada. He is listed in the Book of Negroes as, "Paris, 19, stout lad."

I wish I could write a factual account, but records are scant. The best I can do is study history and then imagine what it must have been like, what he must have been like as a child born into slavery, a teenage soldier, and then a young free man in a harsh and cold new land where British promises weren't exactly kept.

Without his bravery, I, in a very real sense would not be here. This novel is to honour his sacrifice because he really did run so I and his other descendants could fly.

My plan is to release 3 chapters, the next one will not be consecutive. Then, you'll have to buy the book to see how it turns out. :)

About the Creator

Misty Rae

Retired legal eagle, nature love, wife, mother of boys and cats, chef, and trying to learn to play the guitar. I play with paint and words. Living my "middle years" like a teenager and loving every second of it!

Comments (1)

Misty, this is fantastic!!! Loved you 2nd Chapter!!!♥️♥️💕