Beneath the Island Sun

Green Tomatoes and Growing Pains

As far as my memory and hearsay combine to form a vague understanding of my history—a mismatch of facts, experiences, and something slightly similar to the stain on my favorite shirt that I don’t really know what the hell it is—I would say that this was, quite frankly, my life. The details may have been nicely airbrushed, like a social media photo, but they still at least bear some resemblance to reality.

In any case, this is as close to the truth as it's possible to get without me actually stumbling into it and spilling my tea—as far as the truth is really real—providing that the very notion of truth didn’t have a falling out with reality and ran off with fiction to some paradise island. After all, truth, much like the sun, is sometimes easier to tolerate when you don't look at it directly.

What is it they always say? The fact that reality is out there gives no reason to believe that it's not all made up. This was my reality growing up, or the reality that I remembered.

Now, where do I start? Well, since the beginning is wherever you choose to start, this is as good a place as any.

On an island in the Caribbean, I went to high school on the outskirts of a lively town steeped in colonial history. Taken from Spain in one of Europe’s empire building musical chairs, the British, in a moment of profound lack of imagination, named the town Spanish Town. It was as if they ran out of names the very moment they took the island.

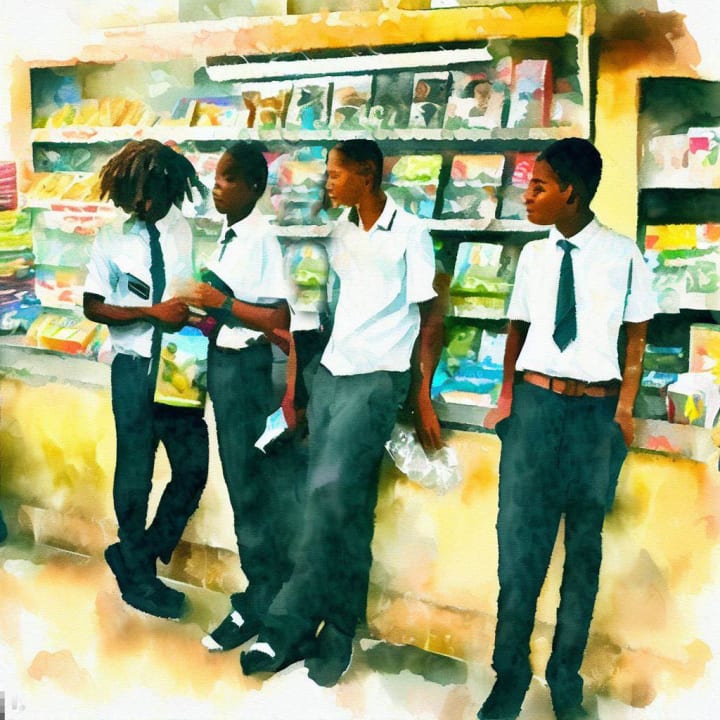

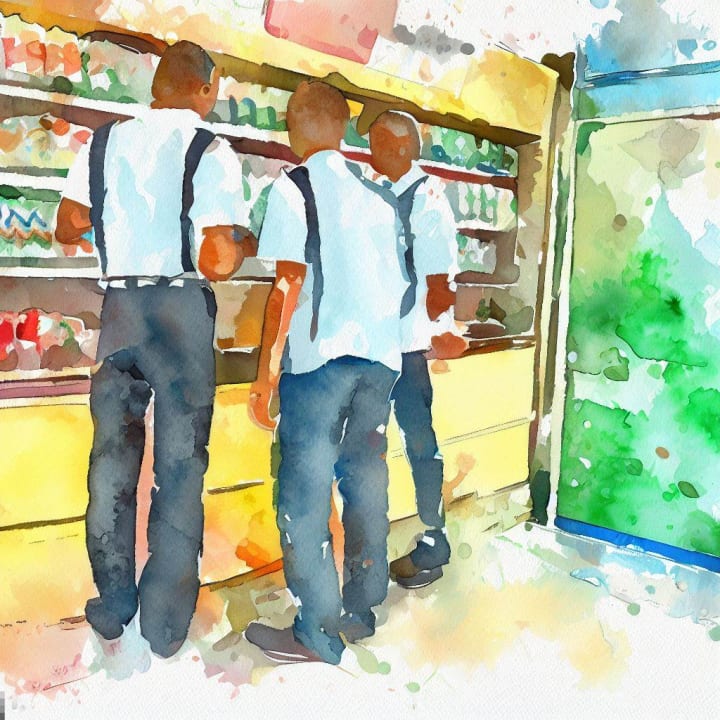

Every Friday when the end-of-day school bell rang, we escaped the confines of our structured learning; all the kids would just pour into the heart of Spanish Town, or Spain as the town folks called it. But Fridays, man, Fridays were different. We’d hang around for hours, soaking up all the life of that town. No teachers—without schedules or obligations—I guess you could say it was our way of throwing off the rigid discipline of a week's worth of schooling, just us and the streets.

In town, the sidewalks were always overrun by vendors. They invaded the walkway like an invasive species with a business plan, taking it over with their goods. Some of them had these fancy setups on tables, shoes, bags, clothing, or whatever toy was trending at the moment. While others, probably the smarter ones, just threw their stuff right on the ground—on sheets, cardboard, whatever they had—making it easier for a quick escape.

The police would bully them off the sidewalks, away from the front of legitimate stores. But as soon as the cops left, those vendors would be right back at it. The art of sidewalking had been all but outlawed by the vendors, leaving us nowhere to walk but in the street.

The taxi drivers had no patience for the pedestrians, honking and pushing their heads out of their windows, telling people to “get di rass outta di way.” It was almost like a toxic relationship. They would cuss us out for being in the streets, then try to sweet-talk us into getting into their taxis.

Some of us had learned very quickly that the professional pocket cleaners were very dedicated to their job, so we started wearing our knapsacks across our chests and stashing our wallets right in our breast pockets.

After walking around for an hour or so, fluttering from food vendor to trinket seller, we always ended up at the same old store, on the side of a cobblestone street that had never been tarred over since colonial days. This particular Friday, it was me, Doc, Bromwell, and Twosee.

Every time I walked into that store, the familiarity of it wrapped around me. I could've walked around with my eyes shut and not hit a thing. We were at that store so much, you'd think we lived there.

We'd usually just hang around by the magazine rack, shoved up next to an ice machine that smelled like fish. That thing hardly worked; it was always conking out. Every once in a while, an employee would come by and give it a good kick to get it started again. And for a few minutes, it would hum and buzz, but then it would make this metallic whistle sound and sputter to a halt.

We were at the magazine rack to check out the new comic books, but mostly we just lingered there, mindlessly combing through magazines, until that internal clock placed in our heads by our parents told us that it was time to head home.

“Hey, Doc,” Bromwell said. “Si da girl de? She looking at you." Go seh sumting no?” People said me and Bromwell favored each other; at first, even the teachers mistook us for brothers. I didn’t see the resemblance, though.

A few girls from our school were at the stationary section, inspecting the assorted collection of colored construction paper, probably needing them for some project they had to complete over the weekend. One with braids seemed especially interested in us, or maybe just Doc. She constantly shifted her eyes in our direction, whispering and giggling to her other two friends.

“Yu know her?” Bromwell pressed.

Apart from Bromwell and I wearing some semblance of our former colonizer’s complexion, his hair was much wavier than mine, and even though we were the same height, he was more on the heavy side. His thick and defined eyebrows contrasted with my thinly lined ones and my shock of red hair.

Doc shook his head. He was about six inches taller than the shortest of us, with a feathering of hair under his nose and chin. The slight shadow against his cheeks looked like a pleasant sunburn. He wore them awkwardly. If anyone were to guess his age, they would have guessed wrong.

I envied Doc. I thought that hair held the key to a world of untold privileges and respect. Every childhood memory is inextricably tangled with a peculiar obsession; for me, it was hair. Hair, or the absence thereof, was my measurement of adulthood, as if it were the gold medal for arriving.

Every morning I found myself in front of the bathroom mirror checking my face out, like some drill sergeant inspecting his cadets, desperately looking for my much-coveted hair, looking for the start of my transformation, my change. Unfortunately, the thing with change is that it’s never evenly distributed among friends, like tomatoes on the vine, some more ripe, some stubbornly green.

Like Doc, some friends blossomed quickly into the ripe redness of maturity, who greedily drank the hormones of adolescents, their bodies transforming at a hurried pace. These were the friends who sprinted ahead.

Then there was me, a stubborn green tomato, as if I were reluctant to bid farewell to childhood. I was the tomato on the vine that, in its happy shade of green, was content with its color. Though mentally unripe, Doc was content with his shade of green. But at the end of the day, we were all tomatoes.

Doc, his shyness tied to his tongue, fidgeted with a magazine that slipped out of his hand. He picked it up and moved to the other side of the rack, behind Twosee, trying to shield himself from the stare. The girl, who seemed almost disappointed, walked towards the register with her friends, construction papers in hand.

“Hombre,” Twosee began. His name was “Mark,” a name that was a distant memory since we found out his nickname from his younger brother, “One look, two see," which his own family bestowed on him on account of his cockeyedness.

“Yu no si shi did a pree yu” (meaning: she was checking him out). Like he normally does, he adjusted his glasses, which were always determined to fall from his narrow face.

“Leave him alone, man. Yu no see he not ready fi all a dat,” I said, not even bothering to look up from the magazine I was flipping through. I could always count on Twosee to make a comment about almost anything.

Twosee lived in my neighborhood; he was the first friend I made in high school. We met at the bus stop on the first day of seventh grade. He noticed that we were wearing the same tie and introduced himself. Twosee lacked the control to internalize his thoughts, always muttering to himself, a habit I found annoying at times.

“Man, if mi look like him,” said Twosee, eyeing Doc. He stroked his chin, a slight frown forming as his fingers met smooth skin, willing the hair he thought should be there to appear. We were all at that age where one first finds vanity and insecurities, an odd mix we drown ourselves in, measuring ourselves against each other, faking confidence, that never quite fits, wearing it as if it were an oversize coat, hoping to grow into it.

“Bwoi, mi can’t wait to beard up,” he murmured, another one of those thoughts that should have stayed internal.

Turning to face the magazine rack, I sucked my teeth. “Even if yu have hair, nobodi would business bout yu,” I said as I replaced the book. “Gad no mek ugly people like yu anymore, Twosee, yu one of a kind.” Bromwell and Doc laughed.

As I searched for another magazine, I noticed one sandwiched between two other publications. Only eyes were visible, but it dripped with seduction, luring me in from behind its plastic shield. Curiosity got the best of me. Before I knew it, my hand was reaching for the magazine. I pulled it from the rack, and just below the title “Hustler” was a picture of a woman in an ungodly pose. At that moment, strange feelings that I never knew existed flooded my mind.

The adult magazines were always sealed in plastic with a blank sheet of paper hiding the cover. The plastic casing on this one, however, was open, and the blank paper was missing. I took it out of its plastic jacket and opened it.

The images inside were even more explicit than the picture on the cover. This must be what people mean when they talk about being drawn to something dangerous. I certainly felt like I was being pulled into some dark underworld that lures you in with promises of pleasure before consuming you whole.

I heard a gulp beside me. I turned to see Bromwell with his eyes wide and an obtuse grin scrawled across his face. “Bomboclaat!” he said, the curse word dripping off his tongue with ease. It was one of four spicy words almost everyone learned before they could even walk, as if we had signed a contract or something, stating that these were the first words we must learn before we’re considered a Yardie.

“Mek, we get it,” he whispered while nodding towards the magazine and grinning slyly at me.

“Get wha?” Twosee asked as he grabbed it from my hands.

“Bomboclaat!” he said as he eagerly flipped through the magazine. Doc, towering over Twosee, stared at the pictures with such intensity as if he were burning them into his eyes before they disappeared from the pages.

We were all thirteen years old, and the chances of one of the cashiers allowing us to buy it were slim.

“Dem nah go mek we buy it,” I said as I grabbed it back from Twosee and slipped it back into its plastic casing.

“Put it inna mi knapsack,” Bromwell suggested.

Even if we tried to walk out of the store with it, there was a big obstacle in our way.

“Man, yu crazy!” I said, pointing my thumb over my shoulder at the guard at the exit. “Yu no si Bigga Ford at the door.”

Bigga, a name given to him on account of his portly physique. It was how nicknames were handed out. It all boiled down to how you looked. If you were a skyscraper, they'd tag you as "Tall-Man." And if your shadow barely touched the ankles of others, they'd fondly, or maybe mockingly, dubbed you "Short-Man” or "Shorty" if you were a girl. The robust, filling out every inch of their clothes, naturally became "Bigga."

The shades of our skin weren't just hues; they were also titles. The deepest melanin was called "Blacka," while the ones slightly kissed by the sun were "Brown-Man" or "Browning" if you were a girl. There were thousands of Short-Men, Shorties, Tall-Men, Biggas, Blackas, Brown-Men and Brownings all over the island.

As if he possessed that parental sixth sense that could tell when children were up to no good, Bigga Ford looked over at us, his hat barely clinging to his head, threatening to topple at the slight motion.

Bigga Ford was always slumped in his chair, looking like he might've just kicked the bucket or something. Every Friday, it was the same story: sleeping or dead, we could never tell. We were always surprised to see him.

"How him a go know? Wi just pay fi di comics like usual and walk out di door," said Bromwell.

"Wha if him ask fi check wi bags?" asked Doc. He might not be much of a talker, but when he does say anything, it makes more sense than the rest of us combined.

This Friday, for some reason, Bigga Ford was on his feet, fighting each breath as he stood there. The straining buttons struggled to keep his shirt around his belly with every labored breath he took, and his tie looked like it was moments away from choking him out.

Although it was the end of November, close to the end of the rainy season—no sun, nothing, just cloudy, rainy, and cold—Bigga Ford was sweating like he'd run a marathon. Drips of sweat ran down to his collar, painting it with a yellow-brownish stain.

We looked away nervously and weighed the embarrassment of getting caught stealing an adult magazine or being embarrassed trying to buy one. When faced with choices, teenagers rarely make the right decision; fortunately, in the end, we made the right choice, albeit for the wrong reason.

We decided that trying to buy it was the lesser of the two humiliations.

Two cashiers worked the checkout; the older lady, her hair perpetually wrapped in a head tie, often had an open topper of food right beside the register. Between every customer she rung up, she rewarded herself, shoveling a spoonful of food into her mouth. The other cashier was much younger, probably no more than 17. The male customers were always hitting on her, showering her with compliments, and holding up the line. "Maybe wi should try Browning," I said.

Once, in a holding-up-the-line moment, she mentioned she was from Seaford, a place on the western end of the island settled by Germans in the early 18th century.

I held the magazine out before us, saying, "So, who gonna buy it?”

It was obvious who would be the one to purchase the magazine. Out of the four of us, Doc looked old enough. But as puberty was kind to his face, it seemed to have stolen his courage; he would probably pass out even before he got to the register. Without hesitation, everyone quickly grabbed their comics and shoved them into my hands. Each of them handed me a five-dollar bill. As quickly as it had begun, they stepped back, their feet tangling. In their haste, it felt as if I had suddenly become radioactive.

I took a deep breath and sandwiched the magazine between the Spider-Man, Thor, Fantastic Four, and Incredible Hulk comic books. With each step towards the register, Bromwell, Twosee, and Doc inched towards the exit, all the while Bigga Ford kept his eyes on them. They got nervous and sprinted out of the store, leaving me to my fate. Their sudden exit shook the last of my nerves. I wanted to throw the magazines away and run for the exit that had just swallowed my friends. It was too late for me, though; I was already at the register.

The elderly woman before me methodically gathered her belongings, each motion drawn out as if she had purposely slowed time to a crawl. She gave me a toothless smile, and I returned her smile with a worried one.

“You want dem inna paypa bag?” Browning asked with her western accent. The island was small enough that, if determined, one could travel the length of it in an entire day. Yet the undulating mountains and deep-set valleys birthed degrees of patois so varied that one could get lost in their labyrinths.

“Paypa,” I echoed, clearing the hesitant knot in my throat with the word.

With the adult magazine stacked between the comics, I stood there nervously hoping that Browning wouldn’t notice the woman on the cover with her flaming bush, posed in an ungodly way.

As she entered the price into the register, she slid each book to the bagging area. The magazine slid close to the old woman, hitting the bag she was just about to lift.

She looked at the picture and created more lines in her wrinkled face. “Nasty pickney,” the old lady said as she looked at me with shock.

“Dat is all inna unnu head.” As she walked out with her back hunched, she gave me one last wicked look before exiting the store.

“Eighteen fifty,” Browning said as she grabbed a brown paper bag. I uncrumpled the five-dollar bills, moist from my sweating hands, and plopped them down on the counter. She grabbed the magazine, looked at it, and then at me. Her hazel eyes, a remnant of her ancestors, teasing me, enjoyed my embarrassment. She slowly let go of it and let it slide into the bag. With a smile forming on her face, she handed me the bag and winked at me.

About the Creator

William Saint Val

I write about anything that interests me, and I hope whatever I write will be of interest to you too.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.