Cross-Dressing in Shakespeare's Comedies

By Doc Sherwood

The comedies of William Shakespeare usually feature at least one female character who dresses up as a man or boy. Shakespeare did not invent this theatrical device, but he used it extensively. The Two Gentlemen of Verona is the first in which a heroine cross-dresses, and Cymbeline the last. Since these are respectively one of Shakespeare’s very first plays, and one of the last he wrote alone, we might say the cross-dressing tendency is a constant throughout the run of comedies.

Shakespeare may have deployed this device for practical reasons alone. Women were forbidden to act on the Elizabethan stage, and female parts were played by boys whose voices had not changed yet. The device of cross-dressing would have made performances easier for these inexperienced young actors, who would not have to pretend to be women while their characters were disguised. Rosalind in As You Like It is the largest female part in Shakespeare and speaks a quarter of that play’s lines. Probably the only way a boy-actor could handle this workload was by appearing in his own gender for most of the action.

In the theatres of today, women play the female parts in Shakespeare. Sometimes though, and perhaps especially when dealing with the comedies, it’s important to remember that these roles were not written for actresses nor originally performed by them.

One of the best examples of this is to be found in Much Ado About Nothing. Hero (which, when pronounced “hey-ro,” is a girl’s name drawn from Ancient Greek mythology) is going to marry Claudio, but the villain Don John tricks him into thinking Hero has been unfaithful to him. Therefore on the wedding day Claudio viciously casts Hero out, and she doesn’t even understand why.

The scene is not remotely funny when a woman plays Hero. A modern audience only feels pity for her, and finds the whole sequence troublingly painful and misplaced in an otherwise sunny and lighthearted play. However, there can be no doubt that on Shakespeare’s own stage, some of the edge of this scene will have been softened by the presence of a boy-actor in the role of Hero. Audiences at the original performance saw its cruelty to women only at one remove, whereas we today see it with a starkness and directness that Shakespeare did not intend.

This is not to make any kind of assumptions about the way in which Elizabethan English people viewed the mistreatment of women. Whether they were any more or less liberated than us in terms of gender equality is not the point. The point is in support of what many scholars argue: that to properly understand and engage with the plays of Shakespeare, we must attempt to return them as far as we can to the context in which they first appeared.

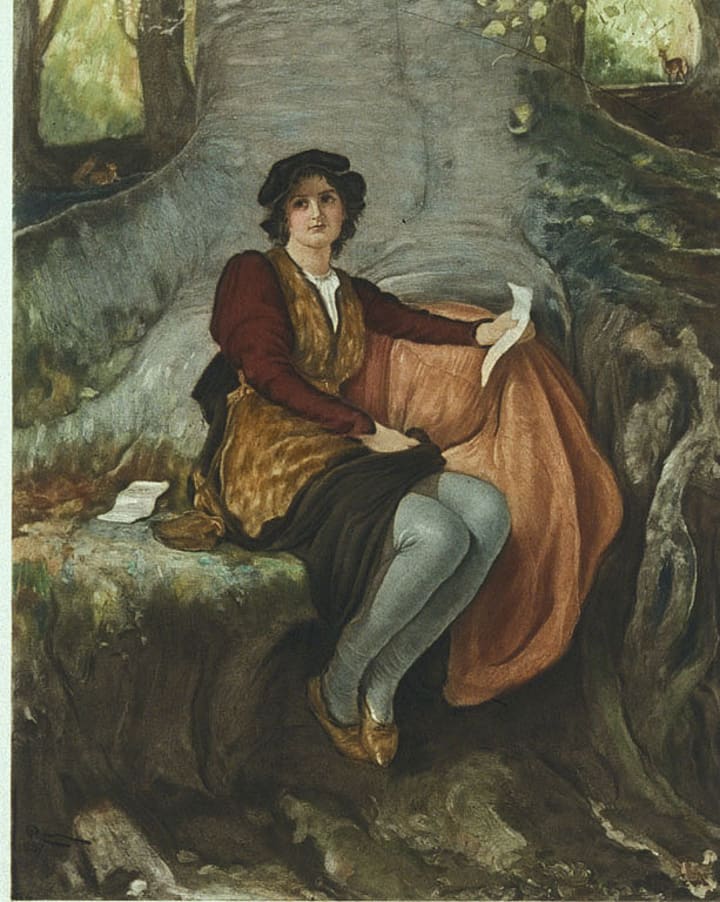

To return to Rosalind in As You Like It, this heroine’s reason for disguising as a young man is at first simple safety, since she’s fleeing from her evil uncle to hide out in the Forest of Arden. What exactly she looks like when so dressed is a very important question facing any director of this play, for reasons we’ll see presently. From the dialogue it’s clear that Rosalind makes quite an effeminate boy, for her male alter-ego is frequently described as “fair” and “pretty.” On the other hand, her disguise must be quite convincing, as it even fools her own father!

In the forest Rosalind encounters Orlando, the man she loves, and she discovers he loves her too. Still dressed as a young man, she offers him advice and training that will help him win the heart of his loved one. She tells Orlando, who believes she is male, to pretend that she is Rosalind and to pursue her as if she were. She keeps it a secret from him that she really is Rosalind.

Her reasons for doing this are usually clear enough to an audience or reader. As her situation compels her to remain disguised, she takes this opportunity to learn more about the man she loves, to be flattered by his words of devotion that are really about herself, and maybe even reshape him a little to her own designs. What might take a little more explaining, however, is why Orlando readily agrees to this strange arrangement.

One possibility is that he’s entirely fooled by Rosalind’s disguise, and believes he’s signing up for nothing more than some productive male bonding. The strangeness of the whole situation, however, makes this unlikely. We’ve seen that Rosalind retains much of her feminine beauty in her disguise, and Orlando himself says: “The boy is fair, of female favour, and bestows himself like a ripe sister.” Perhaps this is what he’s drawn to, and maybe he even sees through the disguise a little. He doesn’t find out that the young man is Rosalind until the very end of the play, but it could be he can tell at least that she’s really a woman, and one who reminds him off the one he loves.

But Orlando also says that in her disguise, Rosalind looks like her own brother might be expected to look. This dimension of their curious relationship has sparked by far the most interest. Why would a man take part in this peculiar mock-romance with someone he believes is another man, and who resembles the woman he loves? Perhaps Orlando sees the young man as a substitute for, or next-best-thing to, his beloved Rosalind. Or it may just be that deep down, Orlando prefers the young man to the woman.

At the end of Twelfth Night, the Duke Orsino marries Viola who has spent the whole of the play pretending to be his male servant. As with Orlando, we can wonder whether Orsino saw through the disguise, or whether he first started desiring her when he thought she was a man. When Jessica is wearing her disguise in The Merchant of Venice, her lover Lorenzo tells her she is “in the lovely garnish of a boy.” This implies he finds her attractive because of the male clothing, not despite it. Scholars of Shakespeare’s personal life have given much thought to such homoerotic elements associated with cross-dressing in the comedies.

Laurence Olivier, who in Paul Czinner’s 1936 film of As You Like It made his onscreen Shakespeare debut starring as Orlando, complained that his co-star Elisabeth Bergner’s “impersonation of a boy hardly attempted to deceive the audience.”

This is fair. The Bergner Rosalind does nothing to disguise herself beyond wearing men’s clothes, instead of the medieval princess outfit used for the scenes when she’s in her true identity. It might be believable that Orlando doesn’t recognise her when she’s dressed up, but no-one could possibly believe she was male.

However, this problem may not be down to Elisabeth Bergner’s bad acting as Olivier implied. Homosexuality was still a taboo subject for the cinema in 1936, and a director who filmed sequences in which two apparently male characters spoke romantically to each other, went through the motions of courtship and even staged a fake wedding would have been seen as inappropriate, even subversive and dangerous. Perhaps keeping Elisabeth Bergner as feminine-looking as possible in her disguise was the only way to ensure the film would be made.

Shakespeare’s original play also contains a female character called Phebe who falls in love with Rosalind while the latter is disguised. This subplot is totally absent from Czinner’s film, presumably because the idea of a woman falling in love with another woman was likewise unacceptable. Paul Czinner was himself gay, and understood these issues well.

We’ve no way of knowing how Orlando, Rosalind or Phebe looked on the Shakespearean stage when As You Like It was first performed, but as they were all played by male actors, it’s most likely they all looked male. Such performances of Shakespeare are seen in the theatre today, but it’s still difficult to imagine a mainstream Hollywood treatment of As You Like It opting for this approach. In that respect, not much has changed since 1936.

When we looked at Romeo and Juliet we saw how it was only through subjecting the original play to a long process of adaptation and reinterpretation that we’ve come to consider this tragedy the greatest love-story ever told. It may be a reasonable conclusion to say of Shakespeare’s most beloved comedies that something of the same is true.

About the Creator

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments (3)

I found this to be very fascinating! I especially loved the story of Orlando and Rosalind! Thank you so much for sharing this piece!

While reading the part about As You Like It, I automatically thought of Edmond Rostand's Cyrano. Nothing to do with the potential "homoerotic" overtones, because there isn't any in that play, but because I wonder if Rostand wasn't unconsciously influenced by Shakespeare's stories when he wrote that one. When I studied As You Like It at university, my professors basically said the same things as you did in your essay. Shakespeare's plays are particularly challenging to perform, especially these days. I prefer reading them to seeing them live, because I notice the liberties actors tend to take with their lines. As much as I like Denzel Washington as an actor, I stopped watching Macbeth after 10 minutes. Now, it's time to tell you that one of my favorite movies is Shakespeare in Love. If you have time and feel like doing it, I would love to read your thoughts about the movie.

The first drag Queen . Now I know where it all started. Excellent informative lesson on William Shakespeare. William Shakespeare sure know how to shake the world with how he cut through the hopes to make it happen. 🥰This is your third lesson on Shakespeare can’t wait for the next lesson 💗👏