Unsinkable: The Aircraft Carrier Made Out of Ice

Desperate times called for desperate measures

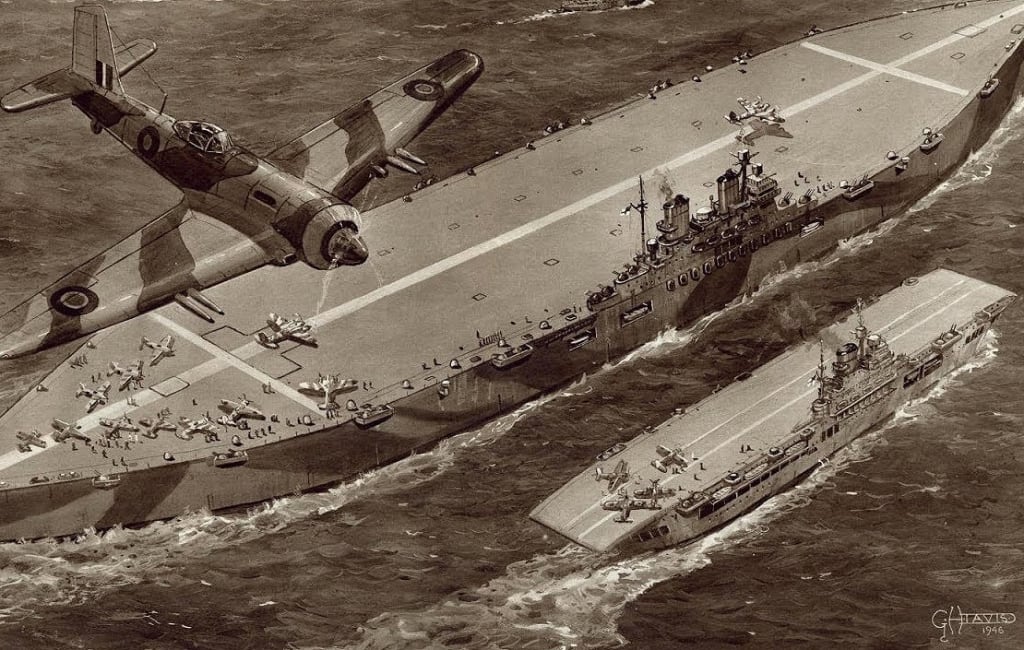

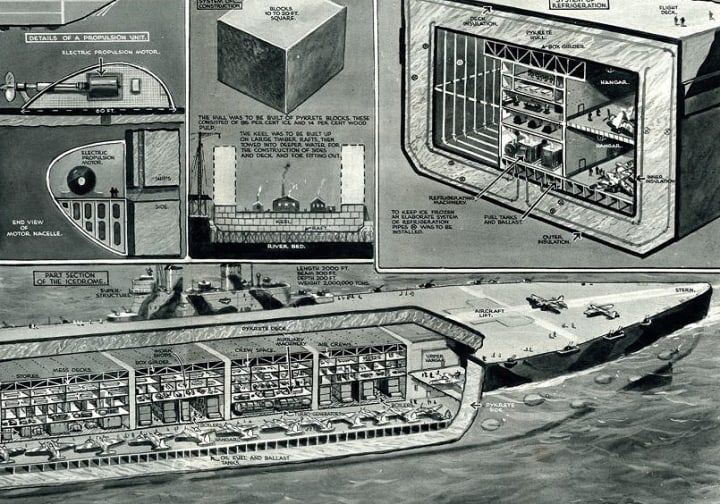

It looked good on paper, a WWII aircraft carrier 2,000 feet long and 300 feet wide, three times larger than any other carrier at the time and capable of carrying 200 Spitfire fighters or 100 Mosquito fighter-bombers. Its size and bulk would make it impervious to bombs or torpedoes rendering it virtually unsinkable. And it would be made out of ice.

In 1942 the Battle of the Atlantic was going badly for the Allies. Close to 400,000 tonnes of food and materiel were lost to U-boats and aircraft in January alone. Britain faced starvation. Merchant shipping needed protection. British scientist, Geoffrey Pyke had an idea. He would build a floating airfield in the middle of the North Atlantic to protect Allied convoys and it would be made out of an iceberg that could be leveled off for take-offs and landings. Outrageous? Far-fetched? Definitely but crisis breeds ingenuity.

The birth of Habbukuk

Born in 1893, Pyke was a conflicted but brilliant thinker. Craving adventure, he dropped out of Cambridge University in 1914 to become a war correspondent for the Daily Chronicle. His time in France didn’t go well. He was imprisoned by the Germans, escaped to Holland and returned to England where he turned his attention to founding a school, Malting House, based on the principals of progressive education. He later played the markets and made a fortune in tin but lost it all in the crash of 1929. During the War he simply showed up at Combined Operations and insisted it hire him “because I’m a man who thinks.”

In 1942 he presented his idea to Operations Director Lord Louis Mountbatten. Pyke called his indestructible floating island Habbakuk after a minor prophet in the Old Testament. Mountbatten was intrigued but instead of repurposing an iceberg, the military wanted a fully-operational ice-based aircraft carrier. Winston Churchill gave the bizarre idea the go ahead and that was that.

Secret Experiments in a Meat Locker

The Admiralty was not impressed. Yes, ice floats but it melts too. Nevertheless, tests were secretly conducted behind a screen of frozen animal carcasses in a freezer underneath London’s Smithfield Meat Market. Colleague and molecular biologist Max Perutz discovered that mixing 14 percent wood pulp with 86 percent water created a tough and resilient building material when frozen. It could be cut and cast into shapes. Best of all the wet pulp formed an insulating shell that kept its interior from melting. It was determined that the warship would be built out of 40 foot blocks. The new material was called pykrete after project leader Geoffrey Pyke.

Design Details

Warship design started in earnest. The hull had to be at least 40 feet thick to make it torpedo proof. The deck had to be 2,000 feet long to accommodate heavy bombers. Its weight and size meant it would be slow-moving, churning through the seas at seven knots an hour compared to 30 for conventional carriers and since on-board engines would generate too much heat – there’s that melting problem again – propulsion would be provided by 26 external nacelles attached to the hull below the water line and driven by electricity. The vessel was to be steered by alternating the speed of the motors on either side of the hull much like a tank changes direction by stopping and starting its tracks but the Admiralty wanted a rudder and that added another technical problem, how to mount and control a device 100 feet high? The cost of these refinements pushed the production costs higher.

A Trial Run in a National Park

Ice flows slowly in what’s called a glacial creep. The more stress that’s placed upon the ice, the more slippage occurs within and between the ice crystals, causing a deformation. The Smithfield meat locker tests revealed that the creep could be mitigated, if not stopped outright, by cooling pykrete to minus 16 degrees Centigrade or 3 degrees Fahrenheit. That however would require a refrigeration plant and a complex series of ducts. The ice surface would also have to be insulated.

To test it out a large scale model, a wooden frame 60 feet long by 30 feet wide containing a refrigeration unit and blocks of ice, was dropped into Patricia Lake in Canada’s Jasper National Park in 1943. Photographs at the time make it look like a floating boat house but the roof was likely a distraction to hide the experiment’s true purpose. Despite initial hiccups the experiment was successful and in fact the structure kept its shape well into the summer of 1944.

Scuttled

The Patricia Lake experiment was a success. It proved pykrete was a viable building material but it also showed that more steel reinforcement and better insulation was needed to make the concept a reality. The vessel would need four refrigeration stations, complex ducting, aircraft hangers, crew quarters, galley and a mess which would consume the huge quantities of steel and aluminum plus cutting huge holes in the structure to accommodate hangers would compromise its structural integrity. The original estimate of ten million pounds or twelve and a half million U.S. dollars ballooned to 24 million threatening to scuttle Pyke’s plans.

In December 1943 Pyke’s ice-carrier was abandoned. Costs certainly contributed to the decision but by late 1943 time the Battle of the Atlantic was turning in favor of the Allies. Land-based could fly farther and more importantly, the Allies were able to meet the U-boat threat with small and relatively cheap escort carriers.

Pyke’s team disbanded went on to pursue other goals. Max Perutz, the scientist who discovered the pykrete formula of mixing wood pulp with water, continued his work in molecular biology, turning his attention later in life to studying the onset of Huntington disease. In 1962 he shared the Nobel Prize for Chemistry.

Pyke wrote a report on Britain’s burgeoning National Health Service, often criticizing what he perceived to be its shortcomings but trying to make the concept live up to its promise. Despite the criticism he’s credited with helping shape Britain’s post-War universal health plan. Pyke died in 1948 after mailing farewell letters to friends and ingesting a bottle of sleeping pills. According to contemporary accounts he was a self-admitted depressive.

Habbukuk’s Legacy

Pykrete as a building material remains an intriguing idea but its promise has yet to be successfully realized. In 1985 the city of Oslo considered using pykrete to build a harbor quay but changed its mind because of pykrete’s tendency to sag under its own weight unless it’s artificially cooled. In 2011, the Vienna Institute of Technology successfully built a pykrete ice dome 33 feet in diameter just to prove it could be done. It melted three months later. In 2015 Canada’s National Research Council took another look at using wood pulp to reinforce the nation’s northern ice roads. The project is ongoing. Pykrete is an interesting idea; it works to some degree but what to do with it? Nobody wants an aircraft carrier made out of ice anymore.

About the Creator

John Thomson

Former television news and current affairs producer now turned writer. Thanks Spell Check. Visit my web page at https://woodfall.journoportfolio.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.