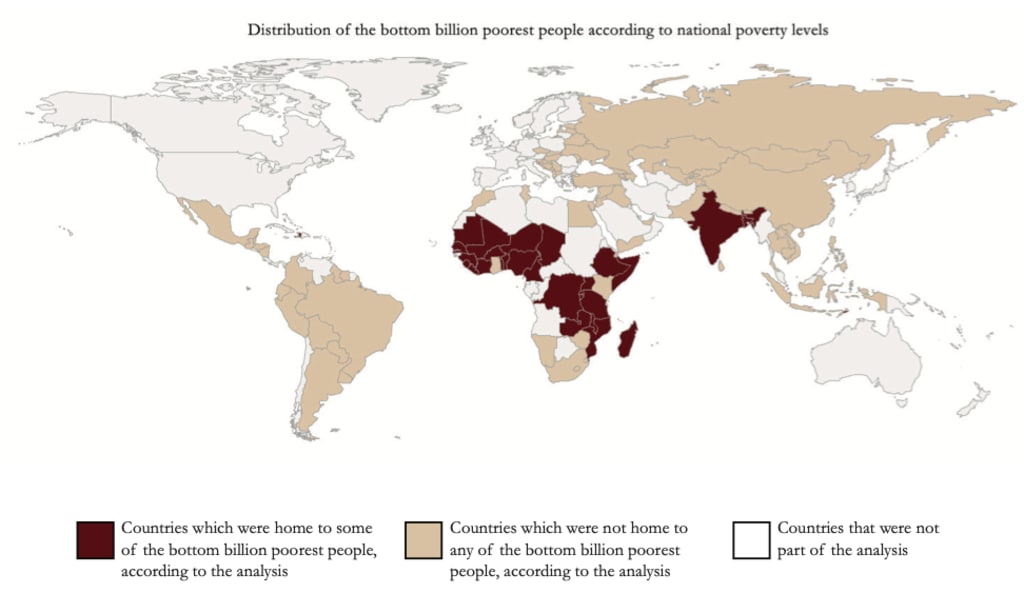

The Bottom Billion by Paul Collier takes a look at the poorest countries in the world, answers the most compelling questions about this population, and then offers solutions. The poorest countries are those developing countries that are at the bottom of the global economic scale, such as Mali, Sierra Leone, Haiti, Afghanistan, and so on. These countries have struggled to keep up with the growing economies of the more developed countries of the world and as a result, now face many obstructions that may hinder their ability to ever climb their way up. Most of the bottom billion are stuck in a destructive cycle that makes it near impossible to break free and join the economically superior.

“The countries at the bottom coexist with the twenty-first century, but their reality is the fourteenth century: civil war, plague, ignorance” (p. 3). There is an obvious discrepancy in how people live their lives depending on their country’s economic status. As the world economy grows and the bottom billion continue to diverge, it will become increasingly difficult to integrate them. Collier cites four distinct “traps” to explain why these countries are stuck at the bottom, however, even those who have been able to break free from these traps in the twenty-first century have additional problems they are faced with: “the global market is now far more hostile to new entrants than it was in the 1980s” (p. 6). Pulling these countries from the bottom of the global economic scale requires a global effort.

Of the four traps mentioned through the book, the first is the cycle of civil war and poverty, in which “civil war is much more likely to break out in low-income countries” (p. 19). However, civil war reduces income and as a result, low income heightens the risk of civil war. Second is the natural resource trap. In what is a paradox of sorts, countries with natural resource wealth end up remaining economically stagnant because their other export activities become uncompetitive and the country is often too poor to utilize the wealth. Third, there's the cycle of bad neighbors: the trap of being landlocked with countries that are not beneficial for growth, transport, and trade. And finally, there is the trap of bad governance in a small country. Oftentimes, the leaders can profit off of corruption that leaves the rest of the country impoverished. What many people may not realize is that the problems of the bottom billion are in reality, global problems.

The likelihood of a country in the bottom billion engaging in a civil war is contingent upon poverty, economic stagnation, and dependence on primary commodities (p. 34). The heightened risk of civil war in a country was found not to be related to political repression, intergroup hatreds, income inequality, colonial history, or ethnic diversity. However, in societies that have ethnic dominance, it is more common (p. 25). Ethnic dominance is when there is one group that makes up a majority of the population, but there are still other groups present that are significant. In most of the societies that are in the bottom billion, there is no one dominant group because of great diversity. Geography and population density are also factors when determining the possibility of civil war. Both the Democratic Republic of Congo, formerly Zaire, and Nepal are at a greater risk because of the DRC’s dispersed population around the edges of the country and Nepal’s mountainous terrain, rather than a flat, densely populated, smaller country (p. 26). In terms of the length of the conflict, countries with lower income are more likely to have long civil wars. Also, having already gone through one civil war more or less doubles the risk of having another; these countries have about a fifty percent chance of making it through the decade in peace (p. 34). This cycle of civil war and poverty will continue until there is outside intervention. What rebels who bring about the civil wars don’t understand is that it is an unsuccessful way to bring about positive change. Those who typically engage in political violence tend to be young, uneducated, and without dependents (p. 30).

One observation that Collier made is that “civil war is development in reverse...once a war has begun, the economic damage undoes the growth achieved during peace” (p. 27, 33). As we’ve seen and studied just over the last few years, “wars create refugees, and mass movements of the population in the context of collapsing public health systems create epidemics” (p. 28). The mass movement of refugees across the world puts stress on the economies and governments of other countries, such as the influx of Syrian refugees in Jordan over the last decade. This is why the bottom billion’s problems are everyone’s problems. The average cost of a civil war to the country, as well as its neighbors, is roughly $64 billion (p. 30). In the decades leading up to the publishing of The Bottom Billion in 2007, approximately two new civil wars were started each year, putting the cost over double the global aid budget. The only option to escape the trap of civil wars is growth. Collier logically points out that “growth directly helps to reduce risk; cumulatively it raises the level of income, which also reduces risk, and that in turn helps to diversify the country’s exports away from primary commodities, which further reduces risk” (p. 32).

The greatest calamity that comes about from the natural resources trap is the “Dutch disease.” The term was coined by economists over four decades ago after the effects of North Sea gas on the Dutch economy (p. 39). The export of these resources raises the country’s currency value, but ends up devaluing their other exports. This can greatly hinder the growth process of these countries.

Commonly an African problem, 38 percent of the people living in the bottom billion societies are in landlocked countries (p. 54). Being landlocked in itself makes it more difficult to grow the economy through trade, transport, manufacturing, etc. These adversities are only increased when you add unsatisfactory neighbors. Switzerland, for example, is landlocked, but has Germany, Austria, Italy, and France, or ‘good neighbors.’ On the other hand, Uganda has Kenya, Sudan, Rwanda, Somalia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Tanzania. Between countries that are stagnant, embroiled in civil war or genocide, collapsed, or have invaded it, this isn’t exactly a favorable position. Landlocked countries must depend upon “their neighbors not just as transport corridors to overseas markets but also directly as markets” (p. 55). Moreover, the costs of transport for landlocked countries depends upon “how much its coastal neighbor had spent on transport infrastructure” (p. 55). Collier offers many recommendations for what these countries can do: increase neighborhood growth spillovers, import neighbor’s economic policies, improve coastal access, become a haven for the region, don’t be air-locked or e-locked, encourage remittances, create a transparent and investor-friendly environment for resource prospecting, rural development, and try to attract aid (p. 58).

The final “trap” that Collier considers is bad governance in a small country. The “small country” portion of this is critical. The example that is given in the book is the disparity between countries such as Chad and Bangladesh. Despite both being countries with bad governance, Chad ends up suffering further from this because of its size and because “Chad’s only option is for government to provide services, and corruption has closed off this option” (p. 66). Since the government plays a larger role in guiding economic development in small countries like Chad, if they are corrupt, then no development will occur.

Collier asserts that the cause for economic stagnation and position in the bottom billion of the world is that countries are trapped in one of the four, or even a combination of these, plights. For us, those who aren’t in the bottom billion, some measures can be taken to help and to give them hope. In a TED talk by Collier, he indicates two forces that change the world, an alliance of compassion for getting started and enlightened self-interest to get serious about it, as well as four foundations of which will assist this: aid, trade, security, governments.

Looking back not too long ago in history, America became serious about developing Europe post-WWII. After having so many countries fall to the Soviet Union, Europe needed to be pulled into economic development. Aid was part of this solution. The Marshall Plan, otherwise known as the European Recovery Program, was put into effect to provide aid to rebuild the economies destroyed in the war. In addition to this, both trade and security policies were reversed. Before the war, America was highly protectionist and isolationist. Following the war, America opened its markets and founded the General Agreement of Tariffs and Trade, placed 100,000 troops in Europe for over forty years, and founded the United Nations, among other organizations.

The difference in this day and age is that we would not be rebuilding nations, but rather reversing the divergence of the bottom billion and enabling them to catch up to the rest of the world. Whether this will be easier or harder, we would need to be at least as serious as America was when rebuilding Europe. Instead of delving into the recommendations made in The Bottom Billion, I will continue to reference the guidance and propositions by Paul Collier in his more recent lecture. Rather than looking at each of the four foundations (aid, trade, security, and governments), he focuses only on governments. The first course of action is to consider the commodity booms of the bottom billion. Due to a range of discoveries, such as oil in Uganda or Ghana, the countries experience an influx of revenue that even dwarfs international aid. In a study of all countries over the last four decades, this appears to have incredible short term results in GDP and “everything else” goes up in the first 5-7 years. However, in the long run, most societies end up worse off than if they had never discovered the commodity, as what happened in Nigeria with oil.

The critical issue found in the comparison of all the countries was the level of governance. Countries that did not have adequate governance, like Norway, Australia, Canada, etc., were doomed to fail. Collier looked at definitive trends, specifically the spread of democracy to identify a pattern, and indeed, democracy had a significant effect, however, much more adverse than expected. Democracy is essentially made up of two components: electoral competition, or how one acquires power, and checks in balances, or how the power is used. Countries in the bottom billion that had adopted democracy, did so in an instant and lacking way, without checks and balances. Because of this, they have been unable to succeed in governance.

An international voluntary standard needs to be put into place that defines key decision points to harness mobilize revenue resources, in addition to governments reporting their revenue to its citizens. While we may not be able to directly change all of these societies in the bottom billion, we can help those who are trying and failing.

References:

Collier, P. (2007). The Bottom Billion. New York: Oxford University Press.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.