Dirty Laundry

"Art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable." -Cesar A. Cruz

If I wanted to get technical, I’d specify in great, gory detail how the tattooing process is essentially a physical trauma by nature. A needle piercing delicate flesh thousands upon thousands of times, literally pounding foreign ink into an unknowing body for what could be hours on end? That's trauma. It's why so many pass out or vomit (or both) after spending some amount of time in the chair. And after all that self-induced trauma, you come out the other end scarred with this masterpiece, minimal or grand, and re-brand it artful body modification for the world to admire. It is what it is and if you're not willing to go through that kind of pain, you just don't want it enough.

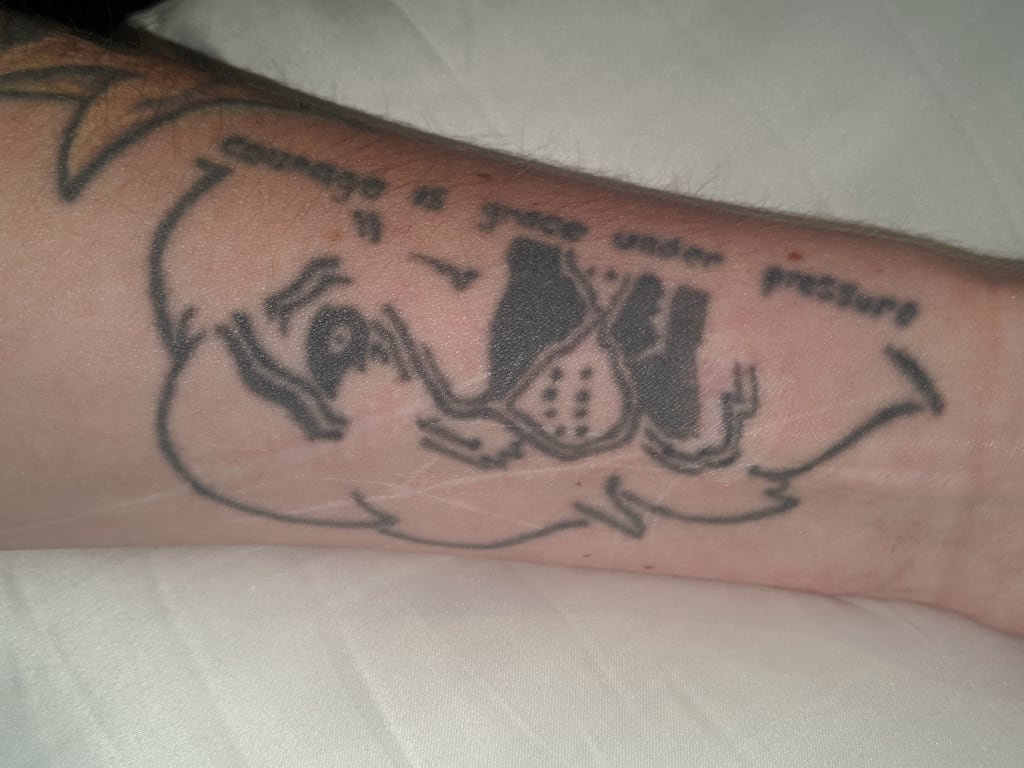

Alright, look. I know you can see it. And yes, you guessed it, I am speaking metaphorically about suicidal temptations. You, like everyone else that studies this particular tattoo of mine, even breifly, notice the pale discoloration of aged trauma: you see the scars. And I bet it's raising some questions for you. So, since I am, in fact, still here on the breathing side of that suicidal impulse, let me elaborate because this isn't what you think:

The only thing anyone actually needs to know is that when I tried to kill myself, I'm not sure I really tried to kill myself. If that makes sense. It had been a long-time ritual of mine to completely destroy my body - cutting, burning, abusing - if only to somehow gain control of the mental and emotional turmoil that manipulated every aspect of my life. And when it all built up enough to drive me almost completely insane. . .well, you know. I lost all control and for the first time, I didn't care.

I could specify - in great, gory detail - on this exact, traumatic act too but for everyone's sake, it's best I keep my mouth mostly shut. I mean, the heartfelt desire was there at least. I was done; I was in constant pain; I didn't want anything to do with anything that involved living anymore; I already felt mostly dead so I figured I might as well make it official at some point or another. But every thought and every feeling I had was just so chaotic and messy, everything was just a flat-line tornado I couldn't get a grip on. A close-to-overdose of Xanax didn't help but at the end of it all, I just started slashing away and hey, if I managed to do some real damage on vital and essential veins, then all the better. Right?

That's not what happened, though.

Turns out, I was screaming and crying and rambling on and on to myself all the while tearing myself apart. My mom woke up and found me. It was a textbook manic episode.

I don't remember much else from that night. Not specifics or logistics, anyway. I do remember being carried out of my room to the ambulance like already-dead weight. Then I remember the in-and-out awareness like a blurred dream I just couldn't grasp. Then I remember the pressure pull of thread underneath my skin. And I remember my sister turning into a sob, away from me, when it was her turn to visit my bed in the emergency room.

After all that, I was mostly awake in the psychward where I was gifted a brand new dual-diagnosis of Bipolar and Borderline Personality disorder. I stayed for a little over a week before going home and nothing really changed; nothing except the overwhelming amount of eggshells that started accumulating across the floors. Not too long after, I checked myself into an inpatient rehabilitation facility. It was one close to home and I checked all the boxes of the treatment center's specialties: mood disorders? Check. General depression? Present. General anxiety? Got that. Self-harm served with a nice side of anorexia nervosa? Yep. Alcohol and drug dependency? That's just a given. Oh, and previous suicide attempts?

I passed the admittance interview before they even said hello.

The minimum time medical professionals suggest you stay in treatment is thirty days. I signed myself out after fourteen. Don't get me wrong; it was a fabulous facility. Clean, comfortable, credibly equipped with impressively licensed doctors and counselors of all kinds. I mean, it was the same treatment center Demi Lovato checked herself into, so it had to be legit, right? But there was just something about it, something about the way the staff worked around it all. It was a fine-line between coddling and making the language or display of the patients' struggles taboo. It was as if they had made it a point to impress this idea that if we don't directly mention it, if we tip-toe light enough around the issues, then the traumas aren't as heavy as they truly are.

It wasn't their fault, I know. It's just how they were specifically trained, how they were educated to handle and heal people like me. It's just that it was all too reminiscent of what my dad always said:

"We don't air our dirty laundry in public."

Well, it was already too late to follow that advice and the growing guilt-trip from the doctors who seemed to offer the same instruction was getting to be impossible to endure. I had to get out of there.

Still, I wasn't worried about it. I wasn't scared. I felt stronger and clearer than I had felt before rehab. In reality, I wasn't but the confidence felt concrete enough; it was a manic, euphoric, delusional "high" that would abruptly conlude with a definition "low," exhibiting doubt, dread, despair, and every other horrible emotion you can come up with.

So, I was home again, feeling misplaced and awkward all over - even with my own family. Mental illness wasn't new to us exactly but making its existence known out loud was. We were never a talk-about-our-feelings kind of unit. So, to have dramatically and tragically announced my struggles undoubtedly upended my family's unquestioned tradition of keeping any uncomfortable topics hushed.

As a result, I took to wearing unfashionably wide wristbands with an excess of thick bracelets. To the unassuming passerby's eye, it would seem that I was just a girl who never learned how to properly accessorize, which wasn't untrue generally, however, it was untrue of these specific circumstances. But do you think I was going to stop everyone that looked my way to explain the reasons for my terrible fashion choices? Which is worse: having no sense of style to the extent of looking like a child let loose in a costume shop or being the crazy, failure that can't control her own head long enough to even end her life the right way?

Inevitably, I walked through my routines, with or without covered wrists, perpetually embarrassed and with a certain insecurity that seemed to run the length of my spine to manipulate every move I made.

Yet again, my thoughts and feelings were all too overwhelming to remain contained. Do you see a pattern here? It was becoming a vicisious cycle of self-depricating proportions.

But I did learn one thing in rehab: trying to hide from your own mind is not only uselss - it’s detrimental. Even the hesitancy to own and overcome your illness only serves to infect those around you with that same skepticsm. And no, I didn’t learn this during some grand, enlightening session with an appropriately accredited therapist. This was a value instilled by the girls and women I lived with, the ones that, like me, had no goddamned clue how to get a hold of their hearts and heads but were attempting the daunting feat nonetheless. It was the way we discussed how denim sticks to blood-laden legs, the way we quipped about absurd lies told in the midst of week-long drunk or stoned benders, the way we shared shameless giggles about gross differences in bowel movements after starving for so long. It was simply the way that any of those girls could say anything, I could say anything, and there were no awkward silences, no up-turned noses, and no shifting blind-eyes. There was just a concrete acceptance and understanding, as nonchalant as discussing morning traffic. But at the end of all those discussions, the recognition and fortified intent that, while these struggles persisted, something must be done because no one can realistically live this way.

I wanted that back. Somehow. I didn’t want to be in constant doubt with myself and the rest of the world. The only solution I saw was a tattoo, one that would shadow the scars but never hide them. As an aspiring writer, I looked to Ernest Hemingway to surmise my intentions: Courage is grace under pressure.

You want to know what the tattoo artist said when I rolled up my sleeve for him to set the stencil on my wrist? “So you’re a cutter, too, huh?”

And there it was: the acceptance and understanding that took breath without question or doubt.

See, against all warnings from my dad or past therapists, I’ve literally branded myself with my so-called “dirty laundry” and it remains mostly uncovered for just about anyone to witness. I’ve come to prefer it this way and here’s why: while they’re looking at my tattoo, I’m looking at them. I take note of that moment when they finally reognize the scars and then, one of two things will happen. Their eyes will widen with the realization of what they’re looking at and quickly grasp at anything else to focus on or they will lock on to that past trauma before meeting my gaze again, continuing on with an implied head-nod or a blink of connected trust.

It’s the latter action I look for, the silent acknowledgement and whispered safety. It tells me who it is I want in my life, who it is that could see who I am past my struggles, and who can love me despite my own occasional lack of self-love.

It’s true, I love my tattoo because what’s not to love about a snarling lion bannering one of the greatest quotes by Ernest Hemingway? But that’s not the body art that has most altered my life by means of consequence or cataclysm. My tattoo isn’t memorable when you ask for notable, tangible worth. The art is in my scars and while I don’t look back on my days of constant self-mutilation fondly, nor do I condone or provoke this particular solution, I’ve found that the memories not only ground my mind, they serve to confess the accepting few that would otherwise pass without the chance to validate my chaotic mind.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.