Practice Makes Permanent 2

Part 3 of Rediscovering Bob Ross

"I'd like to assure you that this is not done by strange fellows with long hair who live in attics and wear berets. It is done by extremely disciplined human beings who are trying to allow you as people...to see through their eyes the visual beauty of this world." -- Vincent Price

There's no doubt in my mind that there is little more to talent than a willingness to persevere. Everything you become good at requires practice. From the most talented beauty guru to your business' DevOps engineer, no one gets where they are without trying something out and discovering they liked it enough to stick with it for years.

Considering that he was largely self-taught, it's not surprising that Bob Ross believed that talent is a pursued interest, and that if one knows the tools, rules, and technique well enough, anything is possible. But there are two things you have to understand before that talent becomes just another part of who you are: you have to understand that you're going to be responsible for your education, and you have to show up. I talk about taking responsibility for your education in my previous article, "Practice Makes Permanent 1", so let's get down to the business of defining talent, and then we'll examine the rigor--a lot of it mine--of honing a craft.

Talent As A Pursued Interest

"People continually say. I can't draw a straight line. I don't have the talent, Bob, to do what you're doing. That's bologna. Talent is a pursued interest. In other words, anything that you're willing to practice, you can do." --Bob Ross, "Bob Ross: The Happy Painter"

In Bob Ross: The Happy Painter, I got to sneak a look back in time at some of Ross' ironic and iconic pop culture appearances on MTV. I am supposedly old enough to remember these, but we didn't have cable until I was 13 or 14, and Ross died when I was 10.

On one MTV bumper, he is a handyman that came to paint a room, which a frustrated art teacher and their equally frustrated teenaged pupils have just vacated. Ross approaches their canvases. They are painting landscapes. He picks up their little brush and promptly tosses it aside, instead taking a two-inch brush from his tool belt and splashing in a quick landscape on the canvas so fast that he is finished before the art teacher and pupils return.

Ross had no time for anyone trying to define talent as anything more than a pursued interest, something that makes someone happy enough to continue it despite the amount of effort it takes to perfect a skill. Ross shared the growing opinion that you didn't have to be wealthy or or formally trained to create and appreciate art. He followed the line of thinking Vincent Price espoused in the 1960s while building the Sears Robuck Fine Arts Collection, that art should be accessible by all. This sentiment was being echoed by the German artist, Bill Alexander, in his television show, The Magic of Painting.

"I feel that a lot of people suffer under two misapprehensions about art. Number one is that it is not available to them, and number two is that it may cost a lot of money. And so I found that my problem in forming this collection is to correct these misapprehensions. To tell people that art is not something for one class of people--economic class, or educated class, but art belongs to everyone...Art is the visual experience of man, made exciting by talent, and the talent belongs to that rarest of all individuals, the artist." -- Vincent Price

Ross embraced the idea that anyone can be taught a skill, and that anyone who practiced enough could build talent, something that so many, even to this day, believe to be some sort of birthright. This is what likely led to his frustration with his own teachers, prompting him to avoid their teaching mistakes in his own lectures.

Ross also believed, though it may not ever have been explicitly said, that in order to achieve success, one has to leverage 20% of what they do know about what they're doing in order to accomplish 80% of the work they are trying to finish. This philosophy is extremely frustrating to those who have "paid their dues" or "did their time" in pursuing the talent of their choice. Whether it's web development, makeup, tattooing, or illustration, the people who had it the hardest will always lambast those who picked up the skill in a shorter amount of time or achieve success quickly. It is for this reason that coding or development boot camps are stigmatized over a four-year degree track despite job requirements that ask for portfolios of past accomplishments, something both educational paths provide. It is the exact reason that the tattoo industry hates the artist known as Johnny Gault for attempting to teach--for free on YouTube--time-honored techniques that traditionally came from unpaid apprenticeships or cost thousands of dollars to learn from other tattoo artists.

The unwillingness of popular opinion to embrace the "fake it until you make it" philosophy it applies to everything else stigmatizes those pursuing an interest to which they had no previous exposure, particularly among the working class. Talent for so long was relegated to the small percentage of humanity that seemed to produce savant-level accomplishments out of thin air, either at a young age or out of some adversity. But this popular opinion of talent glosses over reality. There are two S's in "success" for a reason: success requires Support and Sacrifice. For some, Support is enough. This means someone else somewhere made it possible for the individual to devote time and energy to the pursuit of their choice.

For others, Sacrifice is necessary. Support is a privilege. Those that triumph out of adversity likely did so at great personal expense, either for themselves or someone else. Support and Sacrifice can come hand in hand, but the idea that the only people allowed to be talented are those who are born with a particular gift is pure drivel. Some are gifted with a naturally good voice, which makes singing easy. Sacrifice is minimal, but Support is vital. Some are gifted with a good ear, making learning an instrument easy. This one might require Support and Sacrifice if the instrument is expensive (which it is).

Either way, those that achieve success only through Sacrifice have very little room for quick wins.

Among the working class, Sacrifice is kept personal. Whatever you do better not impact someone else (it's not fair, but it's true for a lot of working artists). Support is a pipe dream. World-famous novelist Brian Lumley's father told him, "you can't eat words." No, but you can write Titus Crow and never have to work a day in your life! This is the kind of salt-of-the-earth philosophy that inhibits working class talent because it stifles the pursuit of an interest in favor of a skill that can be monetized. Art, for the sake of art and for the pursuit of happiness, has very little to do with profit. Art improves quality of life in general. The act of creating builds a sense of abundance and provides meaning to an otherwise difficult existence in which scarcity and want are a way of life. This is the flip side of Sacrifice: in order to make the money to buy the materials to make the art, we have to work, which leaves very little time for doing the art that we're working so hard to buy the stuff for.

The beauty of Ross' art and the comfort in his own philosophy that anyone--anyone--can create art is that the technique he employs is fast and includes "cheating" that leverages only about 20% of all the skill needed to mix color and apply brush to canvas. Far from beating artistic definitions into the ground and forcing 3 hours a day of extra study onto the student (looking at you, Nicolaides!), the only thing Ross insisted upon to really become talented is practice. There is a subtle understanding in The Joy of Painting that you are going to waste a canvas or two doing mountains, or clouds, or criss-crosses in the sky. For working class individuals like me, this is an unhappy but necessary evil; however, in the grand scheme of things, it's no more or less expensive than not picking up side gigs to pay for student loans so that I can spend my weekends and evenings writing an X Files fanfic. That kind of practice looks free, but it isn't. It costs me time. It's work that I can't monetize. No one is going to read that piece. Half of all the many hundreds of thousands of words--and I'm being literal here--that I have put on paper (digitally or physically) will never be read, and that is going to be true of all writers.

However, if it's one thing that I have learned in 36 years, it's that the truly wasteful approach to art is not showing up. Just like wealth, art and talent shouldn't be hoarded. It has to be expressed. Materials have to be used. If you're trying to pursue talent and not practicing with your tools and time, you're just a dragon, and no one wants that.

The Art of Showing Up

"I really believe that if you practice enough you could paint the 'Mona Lisa' with a 2-inch brush." --Bob Ross

Bob had little formal education beyond the ninth grade. Everything he learned, he learned by educating himself, attending art classes at the U.S.O. in his spare time; by practice, by picking up the brush and the pallet knife and trying, he honed his talent and sharpened his eye. Bob Ross wasn't afraid of not being good enough, or if he was, he never showed it. He just showed up. Perhaps more important than realizing how much you don't know about something is being willing to walk up to the canvas, open the laptop, sharpen a pencil, or practice scales.

Get ready to flash back to little Ashley McGee, 2003.

I got the idea to teach myself to draw from a math assignment. We had to do geometry to figure out the coordinates of points on graph paper. Once we figured that out, we had to connect the dots we plotted and color it in. It was Kang from The Simpsons, my favorite show. I sat at my aunt's drafting table over spring break and perfected the dot connections, smoothing them out. I used my expensive markers for the illustration. I was very proud. Some of the best students in my class glanced between my assignment and theirs, wondering what they did wrong. It gave me the idea that I could imitate any illustration, or the lines of any person. I started taking an image (cartoon or otherwise) and recreating the outlines as close to perfectly as I could by eye.

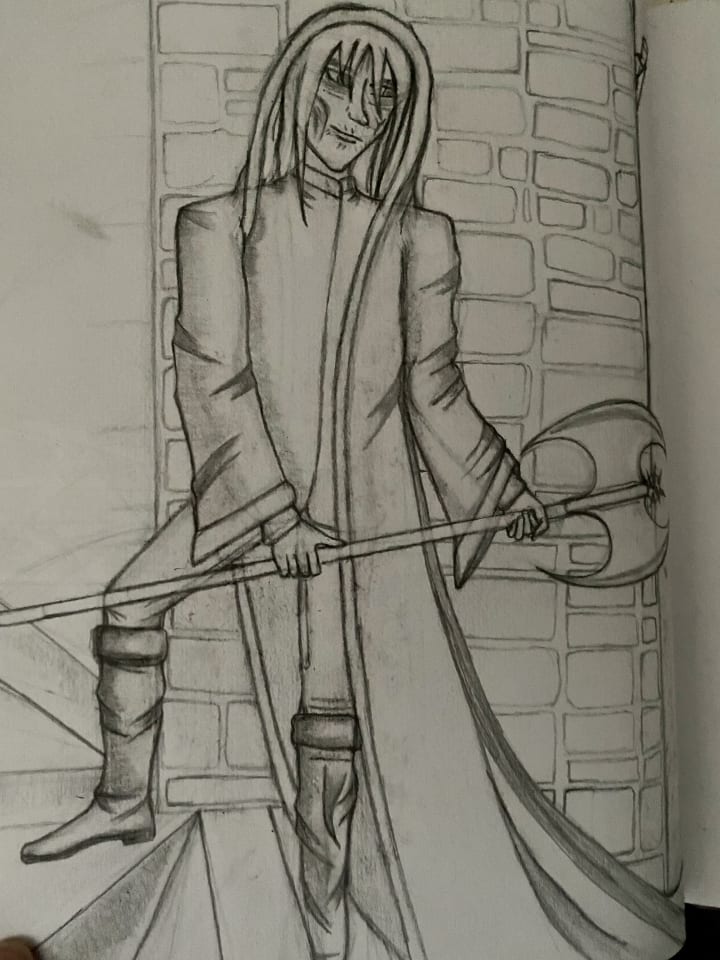

I knew I was just imitating what was in front of me. Nothing about what I was doing was original, and I had no interest in allowing anyone to see my particular flavor or style. After all, I wasn't the one with any talent. I was purely interested in seeing whether or not I could recreate what I saw. That was what I thought drawing was: using lines to create an image. In the back of my mind, I knew that couldn't be accurate. After all, my very artistic friends made animals into people, posed them, put them into backdrops, and illustrated comics. Yes, lines are involved, but it's far from the only thing that makes a picture. It took about 3 years to get to the point where I was confident enough to draw my own ideas, and it didn't turn out half bad.

Later, when I began studying self-taught art with the Nicolaides books, I realized I might have been serving myself well because what I was doing, following lines with my eye and seeing the line, not what my brain thought it was, is called contour practice. Though I wasn't creating planes or shading, or practicing line variation, I was teaching my brain to see contour, and then I was recreating it. My contour exercises, of course, lacked perfection because in practice I was not after a finished piece.

Next up was gesture drawings, a single line from start to finish intended to capture movement. I did thousands of them. I would sit at Starbucks--for lack of money to go anywhere else--and do gestures of people drinking their coffee, walking, and the birds flitting from the tables to the ground. I believe this is one of the most peaceful times of my life. I still remember how bright the sun looked on the patio, and how cool the Autumn breeze felt, and how blue the sky was. Everything breathed; everything was alive. I was happy.

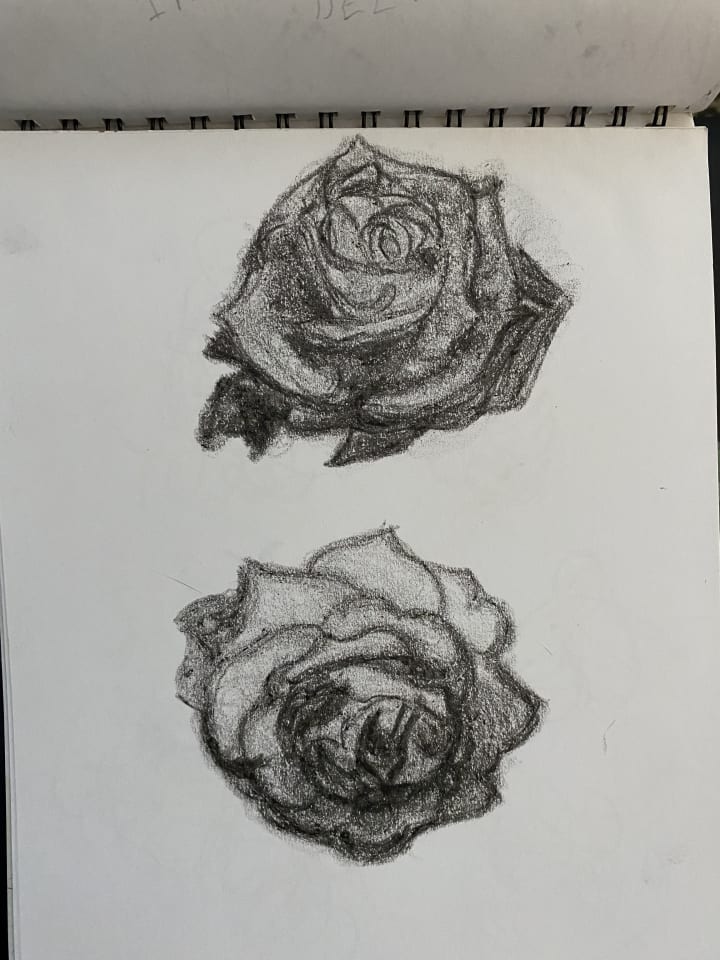

After that were weight and model drawings, where you use a conte crayon not to draw a subject, but to imagine where the subject is heaviest. Are they leaning on something, are they carrying their weight a certain way? Where are they pressed into the chair if they are sitting? The way this is done is by darkening the parts of the subject that are furthest away from you. This is easy if someone is sitting in a chair, but how do you do this if your subject is a tree, or a lamp, or a cup? I did weight and models of everything I could find, even shoes and office chairs.

Before leaving my first husband, I practiced for three hours a day, and began to get very good at gestures and weight-and-model drawings. To this day I typically start any drawing with a gesture before building out a weight-and-model.

It's not art, but it's all I got to before my ex-husband ruined it for me. Anything he couldn't co-opt he made just not fun. During those days, I had no formal instructor, just a book and some examples, and the Internet. Any answers I couldn't get from the book, I tried to get from the Internet, and everyone's opinions were so different, I found I had to make my own decisions about how to proceed.

"Practice makes permanent. No one is perfect, and you'll never be perfect. You could practice your whole life and never be perfect, but if you practice something often, you'll make it permanent." -- Hope Phillips

Unfortunately that's where my art practice ended for a bit. It wasn't until I started entertaining the idea of becoming a tattoo artist that I picked any medium back up. I enjoyed watching digital composite tutorials, but the real fun began when I followed along with the Broken Puppet on YouTube while he drew Hanya masks, lotuses, peonies, and dragons.

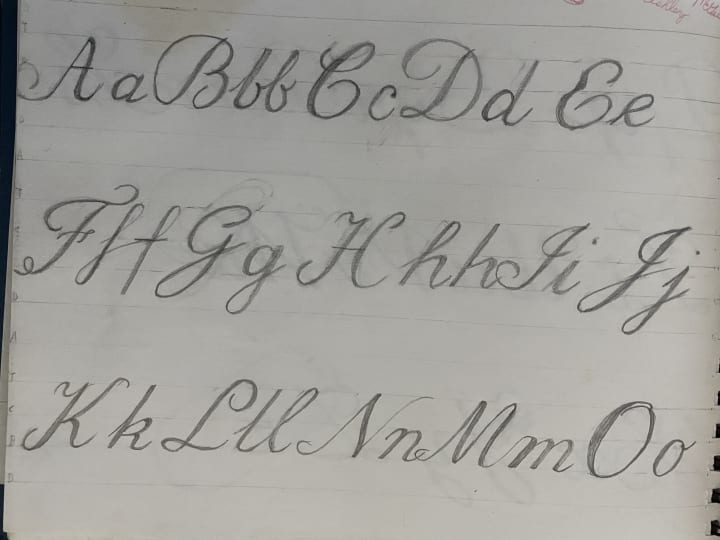

I went to the library and got books on hand lettering, and began to mimic the English and French hands with both pen and ink nib and in pencil. I did gestures of roses and did weight and models of flowers.

I had been extremely interested in web design, and I learned quickly that I could translate what I wanted to do Photoshop into code. Once I learned those basic things, I opened a door to dashboarding data, and it turns out, data is like a fine contour line, and the tools to display it were my paper and pencil. During the boot camp, I exemplified my artistic skills in my dashboards.

It didn't matter to me then if I knew what I was doing. I was unemployed and hurting. I had to do something. I had no prior skills, but I was determined to learn. I didn't have expensive materials. I had pencil and paper. I reveled in watching my progress. I discovered that if I wanted to draw something, I only needed to sit down and do it. It would not always be exactly what I saw in my imagination. I wouldn't always articulate what I wanted the first time. Often what I drew the first time was thrown in the trash. I learned to stop worrying about perfection, that anything I could do once, I could do again, and probably better.

Every time you practice, you learn more. -- Bob Ross

My photography attempts held much of the same. I began using makeup when I was about 31 years old. I practiced glam and special effects with my friend, who had some downtime before grad school at Yale. I knew what I was doing was beginner work, and nothing of what I did was ground breaking. I threw some makeup on and pretended I was David Bowie, Cardinal Copia, or Johannes Eckerstrom.

Not that any of the main takeaways of this experience were obvious to me at the time. It's only in hindsight that I see myself with the same childlike exploration that gave me the confidence to call myself a writer by the time I was 18. I did not see in myself the same kind of harmless audacity it takes to pick up a new skill and dare to become proficient, or even prolific in it. I just started showing up. I got up in the morning and made art (wasn't much else to do when I didn't have a job). I tried everything, ruined it, and started over. I would start a design on a giant grid, lay down an alphabet, wad it up and do it again. If my program didn't work, I didn't beat myself up. I cleared the file and started over.

I'm not perfect at any of it, but the more I worked on something, the more permanent it became. I stopped practicing after I started the boot camp, but I can still write in cursive; I'm still fond of drawing, and Photoshop is as natural to me as breathing. I can throw down 39,000 words in four weeks.

I'm not an expert. But that is not what Bob Ross is asking you--me--to be. He's not asking us to have any prior experience, or to become experts immediately. He knows we're going to stumble at first. He knows we're going to have questions. He's not asking us to memorize vocabulary--which is typically where you start. He just wants to show us some basics, and we take it from there. He's not asking for three hours a day. He's asking you to show up to begin with.

I knew I wasn't going to be Instagram famous, or start a YouTube channel. I knew no one was interested in my David Bowie looks or my obscure band references. I was making the art I wanted to make. I showed up to the camera, to the eyeshadow palette, to the page regardless of whether I wanted to or not, knowing that if I didn't, I would regret it.

Looking Forward

Talent as a pursued interest doesn't absolve the pursuer of the work and rigor that goes into honing a craft. To be considered talented, someone has to practice, even if the practice isn't really art. The purpose of my examples and my experience is not to prove that I am talented, but rather to prove that just by trying, even a slight proficiency and prolificacy is possible. One cannot really call themselves talented either; it's an opinion bestowed upon someone by others. This is the difference between gatekeeping an artistic medium and earning the title of an artist. Anyone can write; to be a talented writer, you have to practice and be peer reviewed. This means not everyone is going to like what you do right away, and what you produce is not going to be good right off the bat either. Seeking to understand what you are lacking and showing up to practice every day builds talent, and even if you're not good at what you're doing right now to the point that someone would decide you are talented, it's important to keep going. We're not going to please everyone, and the point of all of this is maybe we shouldn't be trying to.

The chief tenant of Bob Ross was that art was not work. He said, "If painting does nothing else, it should make you happy." This is true of any pursued interest. There will be work required in order to improve your craft, but it should be work that you enjoy. I haven't ever painted before, but I've made enough art to know that I can expect to slog through some portions of it, and that I'll have to fight with myself a little bit too. My hope going forward is that I can find it within myself to forgive myself for mistakes.

As I begin practicing the one or two things I feel will be necessary to make the best use of my time and the expensive materials I'll need for painting like Bob Ross, I'm trying not to look forward to being good at something. I'm looking forward to learning something. I'm looking forward to feeling free to take as long as I need, to take the time to mess up--a lot, probably. The joy that I look forward to is picking up a skill without the intention of being able to monetize it, like I have with my writing and web development. I look forward to starting and finishing a piece in one sitting, and I chiefly look forward to exploring a medium of art that poverty and necessity haven't ruined for me.

We mistake our inner fear of failure as criticism all the time. I hope for an inner Bob Ross to stand behind me while I work, not to nod in satisfaction at a job well done, but to pat me on the back and congratulate me on my effort. Instead of my inner critic wanting to know why I didn't do better, I hope my inner Bob will be proud that I showed up.

And if someone thinks I'm talented? Well that'll be just fine.

About the Creator

Ashley McGee

Austin, TX | GrimDark, Fantasy, Horror, Western, and nonfiction | Amazon affiliate and Vocal Ambassador | Tips and hearts appreciated! | Want to see more from me? Consider dropping me a pledge! | RIP Jason David Frank!

Reader insights

Nice work

Very well written. Keep up the good work!

Top insights

Easy to read and follow

Well-structured & engaging content

Expert insights and opinions

Arguments were carefully researched and presented

Eye opening

Niche topic & fresh perspectives

Heartfelt and relatable

The story invoked strong personal emotions

On-point and relevant

Writing reflected the title & theme

Comments (1)

This was very inspirational! I loved the three parts of the series. And you are indeed talented!