What Cost Are You Willing to Pay Tomorrow?

Hint: it's higher than you think.

For nearly twenty years, I’ve written software. Most of the development I’ve done has been in old-school Visual Basic. There’s still an active developer community, but VB hasn’t been developed as a language in many years. Essentially, it’s dead.

Knowing a dead language can, at times, be useful. There are legacy products out there that sometimes break and someone needs to go back to a codebase to figure out why it broke then develop new functions and subs to solve new problems with old technology. . .maybe. The threat of encountering new problems that can’t be solved with old technology grows with each passing day.

Unfortunately, my skills haven’t grown as fast as the changing of the digital tides.

Recently, I started a software development company. The products we’re working on utilize newer frameworks like Python + Django, Dart + Flutter, and PHP + Laravel. These are languages and frameworks that are being actively developed and have huge developer communities.

At times, it has been overwhelming as I try to get up to speed with the other developers on my team. So many times, I’ve given in to the overwhelm and consequently haven’t learned anything.

Right now, I’m learning Dart + Flutter. Because the Flutter framework is being developed so rapidly, even the widely accepted online courses are always just a little out of date. That makes things challenging as well.

In short: my repeated inaction has the potential to turn into a costly problem for my company. I’ll only write a fraction of the code, but in a startup environment, it is important that everyone “pull their weight”, even the guy signing the paychecks.

-----

Expanding beyond my microcosm, inaction is recognized as a developing societal issue. We’ve heard a lot about the “Great Resignation” in recent months. Many people have left regular jobs and launched into the world of entrepreneurship. Many, many more, however, have just stopped working altogether. They’re no longer contributing to the economic engine in meaningful ways. Even worse, some have chosen to rely on social programs to keep them afloat financially which puts unnecessary burden on the people who are still paying taxes.

In August, 2008, Harvard’s FXB Center for Health & Human Rights began an initiative to study the impact of inaction. They found:

Inaction can lead to negative consequences for individuals, families, the community, the economy, and society as a whole. These negative impacts can be financial or economic, but more generally will also include health impacts, education impacts, social impacts, and consequences for labor-force functioning.

Short version: inaction is costly.

-----

Here’s a stark example that fits neatly into the summary provided above.

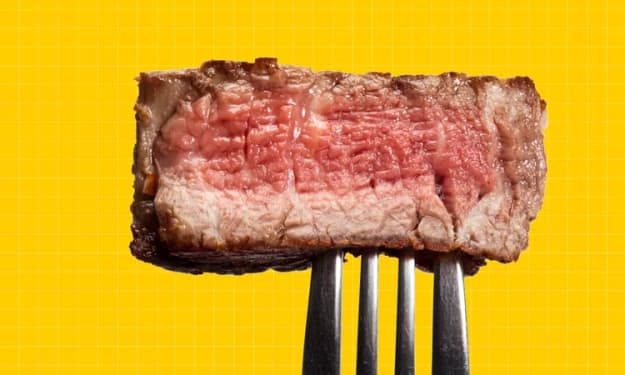

I was recently on a cruise with my family. Each morning, at breakfast, I was struck with awe as I watched people — who, if they went to a doctor, would be likely be diagnosed as medically obese — pile their plates high with foods loaded with sodium, fat, carbs, and bad cholesterol.

Obesity is linked with type II diabetes, numerous cancers, and cardiovascular disease, among other ailments. In 2019, the number of people who died from cardiovascular disease alone was estimated at over 18.5 million globally.

What are the current healthcare costs for those people? What will they be in 5 years? 10 years?

How much has their inaction to get healthy cost them now and what will it cost them before it costs them their lives?

-----

Most of the time I don’t eat well. I’ve spent years justifying my poor diet because I also exercise hard. Over the last few years, however, my ability to keep off the pounds has diminished meaning that I’m now in the majority of people who can no longer out-exercise a bad diet. Consequently, I’m about 20 pounds heavier than I’d like to be.

Running is my go to exercise, but I recently developed plantar fasciitis. Almost overnight, I went from running 30+ miles per week to fewer than 10, and I wake up regularly with pain in the bottom of my feet. After sitting for extended periods, the first few steps look like those of an 80-year old man with hip problems.

If I were 20 pounds lighter. . .

If I had made a decision two years ago to improve my diet, I might not have the problem with my feet I have today. Inflammation, like obesity, is linked to all kinds of health maladies. Plantar fasciitis is, by definition, inflammation.

Now, I have a cost to pay. If I can’t rehabilitate my feet on my own, medical intervention will be required. Fortunately, it’s something that can almost always be handled by physical therapy and rest.

But there will be a cost directly related to my inaction.

-----

The adage that “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” is apropos. While it may be difficult to accurately measuring the cost of prevention vs. the cost of treatment because of all the complexities involved, there are some pretty dramatic studies from recent years that indicate an ounce of prevention is worth far more than a pound of cure.

One such example: in 2017, the CDC found that “reducing the prevalence of hypertension in the US by just five percent would save the economy $25 billion”.¹’²

The issue of prevention vs. cure extends beyond medicine to other areas of our lives. Delaying decisions vs. taking action leads to massive productivity loss that costs an estimated $2 billion (roughly $13 annually per adult worker in the United States).

In many scenarios, we don’t consider the cost of inaction. Even on a small scale, there is a cost associated with inaction. According to the CDC’s study I referenced above, that cost is $72 per person living in the US — and that’s only just five percent of the issue. How many other societal issues are either caused by or exacerbated by inaction? The accumulated costs must total in the hundreds of billions of dollars in the United States alone.

Don’t you think it’s time to count the cost of inaction? In very real ways, the cost is much higher than you realize.

-----

Thanks for reading!

-----

¹Personally, I have a hard time believing the validity of this study. A 100% reduction would equate to economic savings of $500 billion which is is 1/40th of the national GDP. I think there are a few more categories in the budget than hypertension prevention.

²Here’s a thought exercise: let’s suppose for a moment that only 5% of the population is aware of the risks of hypertension. Using round numbers, that means around 325 million people need to be educated. If it requires $25 per person to provide that education, that means around $8.2 billion would be the total educational spend as opposed to $25 in treatment, more than a 3-fold reduction in spending.

About the Creator

Aaron Pace

Married to my best friend. Father to five exuberant children. Fledgling entrepreneur. Writer. Software developer. Inventory management expert.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.