Breathe in.

Hold your breath.

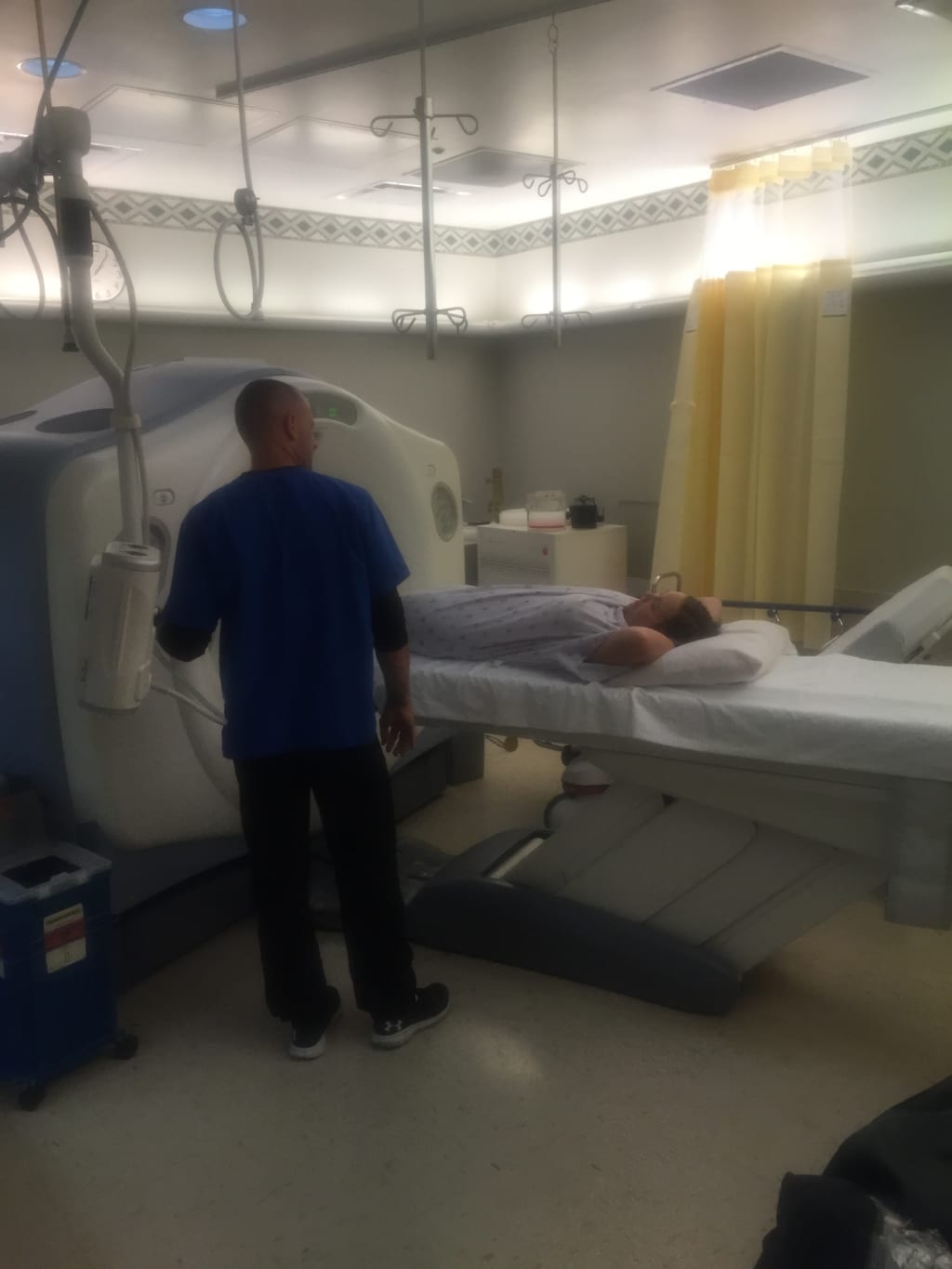

A metal casket turns around me as I lay as still as stone. The hospital gown does nothing to diminish the cold of the table beneath me. Eyes peer at me through a layer of glass; the faces, the eyes belong to share a laugh. With my hands clenched and my breath caught in my chest, my lungs begin to sting. There is a fire tingling in the lowest part of my lungs, which beg for air. However, it is nothing compared to the knives, the invisible daggers that dig into my body over and over again.

Breathe out.

Scenes of blue skies cling to the ceiling, pathetic paper plagiarism of the real world. Inside the whitewashed walls, there is no sandy beach or crystal blue sky. The clouds that are painted on the ceiling’s fluorescent lights are forgeries of a real day. This is the trick that is played on the sick, a pathetic attempt at peace in a world of chaos. I stare up at a fake sky because more often than not the real sky is a picture outside of a window. There in the abyss of illness, I become the corpse of a life once lived.

Breathe in.

Hold your breath.

Sitting in my spinning metal dungeon, I try to count the number of times that I have been stuck in this place. When something is wrong and no one knows what, the doctors in lab coats use the metal monster to try to find answers. I was seventeen when I first visited its chambers. That’s what happens when you get hit in the face with a baseball bat in drama class. (The girl who had hit me cried for a week and I couldn’t go to sleep that night.) Then, when I was eighteen I had kidney stones for the first time. That was the morning I screamed on the floor of an urgent care bathroom, crying so hard I couldn’t breathe. A stranger found my mother who drove me to the ER. That morning was the first time in my life I thought I was dying. The metal machine told me the truth— the pain did not equal death, just a stone in my kidney. Stones filled my kidneys two more times in the next two years, and the metal machine was there to tell me exactly where. I’ve lain in its clutches as iodine coursed through my veins like cold poison and clenched my eyes shut as the noise of the beast stormed my ears.

Breathe out.

Exhaling the air from my aching lungs, I glance at the IV glaring back at me. The nurse had blown straight through my vein the first time. It took two more nurses to get it right. Even in that moment, I knew it would leave a scar. No one likes to talk about scars unless they have a cool story: the stitches someone got from jumping off the swings, or the skinned knee that was so impressively bad it healed into a forever reminder of the fall. On my metal slab with the IV in my hand, I want to be proud of the little scar that no one will ever notice but me.

That little scar is my body. I am broken in a way that is invisible to the naked eye. I’ve scanned my body in the metal coffin four times in the last three years. I have pumped over 2,000 x-rays worth of radiation into my five-foot-one-inch frame to try and find the truth. It came up with stones or it simply came up empty. Lying in my metal casket, I want to pound at the walls and silence the automated woman that keeps ordering me to breathe and breathe out. The radioactive pictures won’t show what is broken inside of me.

When no one knows what is wrong with you they try everything to figure out why. I’ve poured chalk into my stomach and let the lab coats watch how my body digested it for three hours. Giving blood doesn’t make me flinch. I’ve had endoscopies, colonoscopies, twenty-four-hour urine samples, monthly shots, all liquid diets, an ultrasound about every few months, and more medication then I can even name. Perhaps that is what I ought to do as I lie on my cold bed, counting everything I have tried in order to feel well again.

Breathe in.

Hold your breath.

The trick when sick is that at first, all you want to know is what is wrong. After you have a name, perhaps then it can be fixed. That is the trick of the game, the losing play that ruins the season. Lying in my mechanical reality of medicine, I realize there is no cure for what I have. Endometriosis is a condition that occurs in one in ten women and it stole my life. Some women have no symptoms at all, and others like myself take pain medication every day in order to get out of bed. It has no cure, no real treatment, and all that can be done is to open me up like a doll and try to remove the bad stuffing.

Perhaps with a larger scar, the brokenness in my body will become more real to those around me and even to myself. The trick of sickness is to hold on to every little thing around you—the way that a doctor truly cares about you, how you do in school, how a nurse tries to make you laugh. When I am trapped in my medical misery, I lay on the cold metal slab and think of happy thoughts. It isn’t the sunshine bursting through fake clouds above me, or even the laughter of the nurses who aren’t feeling my pain. Instead, it is found in the presence of my parents waiting in the hospital room for my return. It is in the presence of a kind friend that asks me on a normal day how I am feeling, and when I tell them how truly hard it is, they give me a hug. There are a lot of things that cannot be cured by medicine yet; some conditions like mine don’t even have a known cause, but there is something healing in hope. It is hard to hope when your own bed becomes the backdrop of your life when a normal day is painted in pain. Hope, instead, is found in the faces of those around me. They are the friends and family staring at me from above the cold CT machine, a picture of what is waiting for me when the test is done.

Breathe out.

I close my eyes once more as the dull circling sound of the machine cuts through the voice ordering me to breathe. The test is ending. I need more pain medication in my IV, and there are still more hours to pass before I go home.

Days in the metal machine aren’t the worst I’ve faced; The true monsters lie in the loneliness of my bed, the despair of feeling left behind. When I was nineteen years old, I spent over half a year in bed. The days blended together like a flip-o-gram. Half a year became one long, never-ending day of my life. We each carry with us little battles that we don’t often share, stories hidden in the deep breaths we tell ourselves to take.

Breathe in.

Hold your breath.

Breathe out.

About the Creator

Becca Volk

Becca is a chronically-ill lady, writes on health, humanity, and what it truly means to be alive. She invites you into her unique world, and the imagination, that comes with being stuck in bed. The world may be still, but words keep moving.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.