What I learned from the pandemic

Covid-19 has been devastating but there is much to be grateful for.

As a teenager, I loved Stephen King’s The Stand. I read it over and over again, terrified of the idea that a virus could bring down our civilization but hopeful in how people would come together as a community to build something better out of what remained. As I grew older, I realized that our civilization could use some creative rebuilding, though I certainly didn’t want it to happen in such a painful way.

In February of 2020, I was already an activist working with local poor and unhoused communities. I knew the people, I knew their struggles, and I knew that they were not getting the information they needed about this new virus. So I grabbed a friend and a table and hung out on busy streets handing out oranges for immune systems, bars of soap, and pamphlets in Spanish and English. Folks appreciated it and promised to start taking precautions.

But over time, as I spoke to more and more people while things were getting worse, I realized that there were some really dangerous patterns forming. As people began to get sick in my area, they were running out of food, toiletries, cleaning supplies, diapers, and other basic essentials. Grocery store delivery services were backed up over a month, but if the people couldn’t work, they didn’t have money to buy food anyway. And, most disturbingly, I was hearing that many companies were not informing workers if their colleagues were sick. They weren’t advising workers to wear masks on the job. They weren’t allowing people time off to quarantine if they needed it. It was horror piled on top of horror, all for the sake of keeping the businesses going and profitable at the cost of real human lives.

Additionally, I was seeing a real split in how children were able to access virtual learning. In New Jersey, our schools did go remote and all the kids were supposed to receive the technology to be able to participate from home. However, in practice, we found that many families were unaware of this and had no idea how to reach anyone in the school district to talk about it. There was also no accommodation for parents who didn’t know how to use the technology or who had language barriers to understanding.

The lack of childcare was also hitting families hard. Parents who were already struggling to stay at their jobs, knowing that one missed paycheck would send their lives into a potentially devastating downward spiral, had to decide whether to pay someone to babysit, give up their work, or leave the kids home alone.

Of course, the conspiracy theories and misinformation were also ramping up. I did come across some people who refused to wear masks, who refused to change any of their behavior to protect themselves or others, because they didn’t believe the virus existed or that it was as bad as we were saying. Unfortunately, I also saw that some of these people suffered for these views, as they fell ill and even died. This was their choice, of course, but the families they left behind are the ones I see, the ones calling for help.

But back in March, as the virus was still gaining steam, I knew that there was going to be a great and overwhelming need and that traditional support systems were going to fail, as they couldn’t ever keep up even in normal times. So I started a mutual aid group to try to address the most pressing needs.

Mutual aid is a type of support that has always existed but is not always recognized since it is not formal or bureaucratic. It is simply regular people helping each other directly. It does not seek to do charity, it does not tell people what they need or make them go through hoops to qualify. It is led by the community itself, understanding that we know what we need already. I have been grateful to see many such groups form across the country. There are lots of great websites and books on the topic, and how it differs from charity, but I highly recommend Dean Spade's book Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity During This Crisis (and the Next) to anyone wanting to learn more.

My own first experience with mutual aid came out of living as a homeless person on the streets of Toronto decades ago. I didn't know the term or theory behind it at that point, none of us did, but our community was full of members taking care of each other. When one person got a few dollars, it was always shared in some way. We watched out for each other, we found resources for each other, eventually some of us shared a home as we struggled to overcome the poverty cycle together. Professionals and charity workers often tried to tell us what we should do, but it was usually inappropriate or impossible. We understood that everything is more accessible to people as a group, and in almost all cases too far out of reach for an individual.

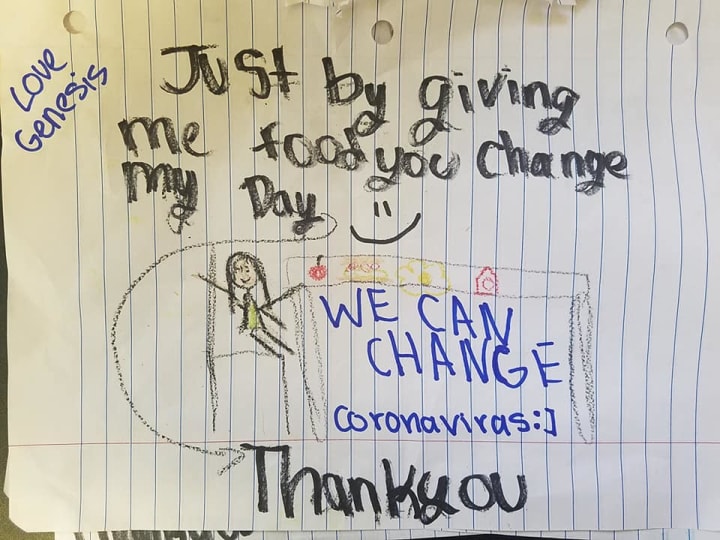

At our peak in 2020, our Covid-19 mutual aid group had approximately 100 volunteers. We have so far helped over 2,000 families and are still going. Using cash donations from the public, we buy groceries and other items and deliver them safely, contact-free, to people’s doors. We talk to schools and municipalities on their behalf and we teach them how to fill out online forms. We tutor their kids and give rides to appointments. We build relationships with the people, calling to check in on them, customizing their deliveries to what they need and want, getting to know them, and becoming friends with them. Many of them become involved in our efforts too.

We worked alongside some food pantries and other food donation organizations, and appreciated their efforts, especially the smaller, independent ones. However, the food provided often didn’t meet the needs of the families and were inaccessible to many of them. Drive-through and walk-up food distribution services popped up all over the country, but if you didn’t have a car, or gas, or availability during their hours of operation, or if you were sick and had to stay home, they wouldn’t work for you. Additionally, many families brought bags of food home only to see that there was nothing in them that they could eat, whether for health or cultural reasons, and in many cases we heard of food that had gone bad, was long past the expiry date, or was infected with mold.

This is why we prioritized buying groceries ourselves to deliver to the families, and we chose to support local, small markets instead of corporate stores. They needed the sales and they were always the quickest to help us in return, by donating food sometimes and by creating logistical systems with us so we could call in orders that other volunteers would pick up.

It bothered me too that people coming to large public food distributions were photographed for social media purposes, having their worst hours shared with the world with a lack of dignity or compassion. At one such event that I will never forget, the organizers actually said that they weren’t going to give out food too fast because they wanted those long lines of people to build up for the photos.

Another organization would actually get angry with us when we would tell them that a particular family was no longer in need of their help. The large, industrialized hunger organizations benefit from having more numbers of families receiving food. There is no reward for them to end hunger, only to increase the numbers of people relying on them to fill the hunger gap. More money comes in, more photo opportunities, more recognition, more hunger.

I want to share one particular story that illustrates how a flexible and direct mutual aid response to need can really do wonders. We got a call from a gentleman who, for medical reasons, could only eat very specific kinds of meals. He did not have access to a kitchen to cook or store food, and so we initially had a local restaurant deliver some meals to him. But then we had a better idea.

After making a few phone calls to friendly people in the area whom we'd been delivering groceries to because they were out of work, we found two who volunteered to cook meals for him. We dropped off extra items with their own groceries that they would cook for him, and a volunteer would deliver the containers back and forth. This was a solution that came out of our freedom to be creative; it allowed some neighbors to get to know each other, and it gave people in a difficult time the opportunity to also help others. His health dramatically improved and he was able to move to a new apartment with a kitchen and cook for himself again.

These are the most important lessons I learned from these difficult (and still ongoing) times:

1. The cost of living in this country is way out of alignment with income levels. Safe, stable housing is a requirement for a healthy life. But many families with unstable or very low incomes are stuck with dangerous, small, inappropriate housing options. I worked with more than one person who paid many hundreds of dollars each month just to have a single room and no access to the kitchen. These people have little to no opportunity to increase their incomes (no matter how much people will tell them to just budget better or go back to school and learn a new skill or move to a cheaper area). There are very few official affordable housing units available, and even they are priced too high for many families. The vast majority of the families we've spoken to have asked for help paying rent, but that is a crisis that we simply can't afford to solve for everyone.

What we call healthcare in this country is also wildly unfair and destructive. I grew up in Canada and never had to worry about being too poor to see a doctor. Here in the United States, I am terrified to become ill or injured because I simply won’t be able to afford it. My insurance premiums are too expensive and my plan covers too little and constantly tries to deny paying for anything. Everyone I talk to says this is normal, you have to keep trying to convince them to approve the bill (though we know that most people are not successful at this). But that’s not right. That’s not an acceptable response. In a modern society, we absolutely should have a single payer solution that actually takes care of people instead of insurance companies.

If people can afford the basics of living healthy, sustainable lives, they will not be in such immediate need after every emergency. We must find ways to ensure that no community member is ever in a place where they can’t afford food.

2. Community matters, and a strong community can make all kinds of things better. I have been so moved by the response to my work from people of all walks of life, a range of income levels, the spectrum of political affiliations. Everyone wants to help during a time of need. Though we ultimately spent twice what we’ve fundraised, people did contribute thousands of dollars to our work and many hours of their time. We received mountains of donated clothes, books, toys, housewares, diapers, and more to give away. We got some local publicity and even had our story published online in The Nation* at one point. So many people have been uplifted by the spirit of generosity we’ve seen, whether they’d been in need of support of not. I don't take credit for this. It has only been possible because of community coming together.

But this shouldn’t only be in times of crisis. As cases of infections here slowed down and the media became less frenzied, volunteers became less interested in helping. As people went back to work, they had less time available to help. Even financial donations dried up and so we are coming up with long-term plans such as starting crafting guilds with the impacted community members, planning to sell the crafts we make.

The families are still struggling, having fallen well behind even the precarious situations they had been in previously. A return to “normal” society doesn’t end the suffering of those left behind. In fact, “normal” society is responsible for the poverty and suffering that so many turn a blind eye to during “normal” times. I’m determined never to go back to “normal” but to continue working to build something new, something more equitable and loving and sustainable. I have hope only because I’m doing this work and others are doing it with me.

I hope you will take this opportunity to get to know your community better. Find the local leaders and grassroots organizations that get too little support. Follow the lead of those who have been fighting because their survival is wrapped up in it, not those who are paid a salary for it. Share things with each other. Ask questions to learn about each other and make connections between people who need something and people who have that thing. Let’s shore up our mutual support so that when the next crisis hits, we will be ready.

It all boils down to this: the systems we want to rely on aren't working for most of us, and we are the ones who will have to do something about that.

And if you’re willing and able to send a tip my way, everything I earn goes back to the community in one way or another. Thank you for your support.

*If interested, the article is at https://www.thenation.com/article/society/coronavirus-mutual-aid/

About the Creator

Theresa Markila

I'm a leftist activist and organizer trying to support myself and help other organizers get the support we need to make change in our communities. Every little bit helps!

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.